The Case for Post-Scholasticism As an Internal Period Indicator in Medieval Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday Is the First Sunday After Pentecost in the Western Christian Liturgical Calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity

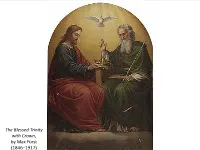

The Blessed Trinity with Crown, by Max Fürst (1846–1917) Welcome to OUR 15th VIRTUAL GSP class! Trinity Sunday and the Triune God WHAT IS IT? WHY IS IT? Presented by Charles E.Dickson,Ph.D. First Sunday after Pentecost: Trinity Sunday Almighty and everlasting God, who hast given unto us thy servants grace, by the confession of a true faith, to acknowledge the glory of the eternal Trinity, and in the power of the Divine Majesty to worship the Unity: We beseech thee that thou wouldest keep us steadfast in this faith and worship, and bring us at last to see thee in thy one and eternal glory, O Father; who with the Son and the Holy Spirit livest and reignest, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF THIS COLLECT? This collect, found in the first Book of Common Prayer, derives from a little sacramentary of votive Masses for the private devotion of priests prepared by Alcuin of York (c.735-804), a major contributor to the Carolingian Renaissance. It is similar to proper prefaces found in the 8th-century Gelasian and 10th- century Gregorian Sacramentaries. Gelasian Sacramentary WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday is the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Western Christian liturgical calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity. It is eight weeks after Easter Sunday. The earliest possible date is 17 May and the latest possible date is 20 June. In 2021 it occurs on 30 May. One of the seven principal church year feasts (BCP, p. 15), Trinity Sunday celebrates the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the three Persons of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, “the one and equal glory” of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, “in Trinity of Persons and in Unity of Being” (BCP, p. -

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

St. Augustine and the Doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ Stanislaus J

ST. AUGUSTINE AND THE DOCTRINE OF THE MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST STANISLAUS J. GRABOWSKI, S.T.D., S.T.M. Catholic University of America N THE present article a study will be made of Saint Augustine's doc I trine of the Mystical Body of Christ. This subject is, as it will be later pointed out, timely and fruitful. It is of unutterable importance for the proper and full conception of the Church. This study may be conveniently divided into four parts: (I) A fuller consideration of the doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, as it is found in the works of the great Bishop of Hippo; (II) a brief study of that same doctrine, as it is found in the sources which the Saint utilized; (III) a scrutiny of the place that this doctrine holds in the whole system of his religious thought and of some of its peculiarities; (IV) some consideration of the influence that Saint Augustine exercised on the development of this particular doctrine in theologians and doctrinal systems. THE DOCTRINE St. Augustine gives utterance in many passages, as the occasion de mands, to words, expressions, and sentences from which we are able to infer that the Church of his time was a Church of sacramental rites and a hierarchical order. Further, writing especially against Donatism, he is led Xo portray the Church concretely in its historical, geographical, visible form, characterized by manifest traits through which she may be recognized and discerned from false chuiches. The aspect, however, of the concept of the Church which he cherished most fondly and which he never seems tired of teaching, repeating, emphasizing, and expound ing to his listeners is the Church considered as the Body of Christ.1 1 On St. -

Antoine De Chandieu (1534-1591): One of the Fathers Of

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): ONE OF THE FATHERS OF REFORMED SCHOLASTICISM? A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2013 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan • 49546-4301 800388-6034 fax: 616 957-8621 [email protected] www. calvinseminary. edu. This dissertation entitled ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): L'UN DES PERES DE LA SCHOLASTIQUE REFORMEE? written by THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: Richard A. Muller, Ph.D. I Date ~ 4 ,,?tJ/3 Dean of Academic Programs Copyright © 2013 by Theodore G. (Ted) Van Raalte All rights reserved For Christine CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ................................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1 Introduction: Historiography and Scholastic Method Introduction .............................................................................................................1 State of Research on Chandieu ...............................................................................6 Published Research on Chandieu’s Contemporary -

Divine Causality and Created Freedom: a Thomistic Personalist View

Nova et Vetera, English Edition, Vol. 14, No. 3 (2016): 919–963 919 Divine Causality and Created Freedom: A Thomistic Personalist View Mark K. Spencer University of St. Thomas Saint Paul, Minnesota Thomas Aquinas argues that God causes all beings other than himself and moves all of them to all their acts, including causing us and moving us to our free acts.1 This claim is connected to the set of issues surrounding the relation between created freedom and divine providence, predestination, and grace. A strong defender of the free- dom of created persons, such as a Thomistic personalist, might reject this aspect of Aquinas’s account and contend that to be free is to be “lord of one’s acts” (dominus sui actus).2 By this, the personalist would understand that the created free person is the ultimate determinant3 of whether he or she acts (I refer to this, following the Thomistic tradition, as the “exercise” of the act) and of what he or she does in those acts (the “content” or “specification” of the act). Throughout this article, I shall refer to the last sentence as the “personalist thesis” 1 Aquinas, Expositio libri Peryermeneias (hereafter, In Ph) I, lec. 14; Quaestiones disputatae de malo (hereafter, DM), q. 3, aa. 1–2; q. 6, a. un.; Quaestiones disputatae de potentia Dei (hereafter, DP), q. 3, aa. 5 and 7; Summa contra gentiles (hereafter, SCG) III, chs. 65 and 67; Summa Theologiae (hereafter, ST) I, q. 22, a. 2, ad 2; q. 104, a. 1; q. 105, aa. 4–5; I-II, q. -

An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems

Discentes Volume 4 Issue 2 Volume 4, Issue 2 Article 4 2016 Poetry Praising Poetry: An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Classics Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation . 2016. "Poetry Praising Poetry: An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems." Discentes 4, (2):7-15. https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal/vol4/iss2/4 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal/vol4/iss2/4 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Poetry Praising Poetry: An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems This article is available in Discentes: https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal/vol4/iss2/4 Poetry Praising Poetry: An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems Annie Craig, Brown University Alcuin, the 8th century monk, scholar, and advisor to Charlemagne, receives most of his renown from his theological and political essays, as well as from his many surviving letters. During his lifetime he also produced many works of poetry, leaving behind a rich and diverse poetic collection. Carmina 32, 59 and 61 are considered the more famous poems in Alcuin’s collection as they feature all the themes and poetic devices most prominent throughout the poet’s works. While Carmina 32 and 59 address young students Manuscript drawing of Alcuin, ca. 9th century CE. of Alcuin and Carmen 61 addresses a nightingale, all three poems are celebrations of poetry as both a written and spoken medium. This exaltation of poetry accompanies features typical of Alcuin’s other works: the theme of losing touch with a student, the use of classical - especially Virgilian – reference, and an elevation of his message into the Christian world. -

Pomponazzi on Identity and Individuation Han Thomas Adriaenssen Abstract. Aristotle Defines Growing As a Process in Which An

Final version forthcoming in Journal of the History of Philosophy Pomponazzi on Identity and Individuation Han Thomas Adriaenssen Abstract. Aristotle defines growing as a process in which an individual living being persists as it accumulates new matter. This definition raises the question of what enables an individual to persist as its material composition continuously changes over time. This paper provides a systematic account of Pietro Pomponazzi’s answer to this question. In his De nutritione et augmentatione, Pomponazzi argues that individuals persist in virtue of their forms. Forms are individuated in part by their material, causal, and temporal origins, which commits Pomponazzi to the view that individuals necessarily have the material, causal, and temporal origins they do. I provide an account of why Pomponazzi was willing to this view. While his opponents remain unnamed, I argue that his arguments for this view are best read as addressing, among others, Paul of Venice and Gregory of Rimini. In On Generation and Corruption, Aristotle describes growing as a process in which “any and every part of the growing magnitude is made bigger . by the accession of something, and thirdly in such a way that the growing thing is preserved and persists” (321a18–22).1 For instance, when an animal grows as the result of the intake of food, all of its limbs grow larger as the result of the intake of new matter, in such a way that the same individual animal persists throughout the process. 1 All Aristotle translations are taken from the Jonathan Barnes edition of the Complete Works. 1 Final version forthcoming in Journal of the History of Philosophy Simple though it may perhaps appear, this definition confronted Aristotle’s later followers and commentators with a problem. -

Robert Holcot, O-P-, on Prophecy, the Contingency of Revelation, and the Freedom of God JOSEPH M

Robert Holcot, O-P-, on Prophecy, the Contingency of Revelation, and the Freedom of God JOSEPH M. INCANDELA In a recent work, William Courtenay refers to the issues in Holcot's writings under discussion in this essay as "theological sophismata."1 That they are. But it is the burden of this essay to suggest that they are more: Holcot's interest in these questions had a funda- mentally practical import, and such seemingly esoteric philosophical and theological speculation was in the service of a pastoral program geared to preaching the faith to unbelievers. For someone in a religious order charged with this mission, questions that may initially appear only as sophismata may actually perform quite different functions when examined in context. Robert Holcot was best known in his own time as a comment tator on the Book of Wisdom. Wey writes that this work "made its author famous overnight and his fame held throughout the next two centuries."2 Wey also proposes that it was because of the rep- utation won with the Wisdom-commentary that Holcot's Sentences- commentary and some quodlibet questions were printed four times 1. William]. Courtenay, Schools and Scholars in Fourteenth Century England (Prince- ton: Princeton University Press, 1987), p. 303. 2. Joseph C. Wey, "The Sermo Finalis of Robert Holcot," Medieval Studies 11 (1949): 219-224, at p. 219. 165 166 JOSEPH M. INCANDELA between 1497 and 1518. His thought was also deemed important enough to be discussed and compared with that of Scotus and Ockham in a work by Jacques Almain printed in 1526. -

Phoronomy: Space, Construction, and Mathematizing Motion Marius Stan

To appear in Bennett McNulty (ed.), Kant’s Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science: A Critical Guide. Cambridge University Press. Phoronomy: space, construction, and mathematizing motion Marius Stan With his chapter, Phoronomy, Kant defies even the seasoned interpreter of his philosophy of physics.1 Exegetes have given it little attention, and un- derstandably so: his aims are opaque, his turns in argument little motivated, and his context mysterious, which makes his project there look alienating. I seek to illuminate here some of the darker corners in that chapter. Specifi- cally, I aim to clarify three notions in it: his concepts of velocity, of compo- site motion, and of the construction required to compose motions. I defend three theses about Kant. 1) his choice of velocity concept is ul- timately insufficient. 2) he sided with the rationalist faction in the early- modern debate on directed quantities. 3) it remains an open question if his algebra of motion is a priori, though he believed it was. I begin in § 1 by explaining Kant’s notion of phoronomy and its argu- ment structure in his chapter. In § 2, I present four pictures of velocity cur- rent in Kant’s century, and I assess the one he chose. My § 3 is in three parts: a historical account of why algebra of motion became a topic of early modern debate; a synopsis of the two sides that emerged then; and a brief account of his contribution to the debate. Finally, § 4 assesses how general his account of composite motion is, and if it counts as a priori knowledge. -

Relations in Earlier Medieval Latin Philosophy: Against the Standard Account

Enrahonar. An International Journal of Theoretical and Practical Reason 61, 2018 41-58 Relations in Earlier Medieval Latin Philosophy: Against the Standard Account John Marenbon Trinity College, Cambridge [email protected] Received: 28-9-2017 Accepted: 16-4-2018 Abstract Medieval philosophers before Ockham are usually said to have treated relations as real, monadic accidents. This “Standard Account” does not, however, fit in with most discus- sions of relations in the Latin tradition from Augustine to the end of the 12th century. Early medieval thinkers minimized or denied the ontological standing of relations, and some, such as John Scottus Eriugena, recognized them as polyadic. They were especially influenced by Boethius’s discussion in his De trinitate, where relations are treated as prime examples of accidents that do not affect their substances. This paper examines non-stand- ard accounts in the period up to c. 1100. Keywords: relations; accidents; substance; Aristotle; Boethius Resum. Les relacions en la filosofia llatina medieval primerenca: contra el relat estàndard Es diu que els filòsofs medievals previs a Occam van tractar les relacions com a accidents reals i monàdics. Però aquest «Relat estàndard» no encaixa amb gran part de les discus- sions que van tenir lloc en la tradició llatina des d’Agustí fins al final del segle xii sobre les relacions. Els primers pensadors medievals van minimitzar o negar l’estatus ontològic de les relacions, i alguns, com Joan Escot Eriúgena, les van reconèixer com a poliàdiques. Aquests filòsofs van estar fonamentalment influïts per la discussió de Boeci en el seu De trinitate, on les relacions es tracten com a primers exemples d’accidents que no afecten les seves substàncies. -

Cusanus, on Learned Igorance-17Z8dxd

On Learned Ignorance Harries 1 Karsten Harries Nicholas of Cusa On Learned Ignorance Seminar Notes Fall Semester 2015 Yale University Copyright Karsten Harries On Learned Ignorance Harries 2 Contents 1. Introduction 3 Book One 2. Learned Ignorance 17 3. The Coincidence of Opposites 30 4. The Threat of Pantheism 47 5. The Power of Mathematics 61 6. Naming God 76 Book Two 7. The Shape of the Universe 90 8. Matter and Becoming 105 9. The Condition of the Earth 118 Book Three 10. The Need for Christ 131 11. Death and Resurrection 146 12. Faith and Understanding 162 13. Death, Damnation, and the Church 176 On Learned Ignorance Harries 3 1. Introduction 1 Many philosophers today have become uneasy about what philosophy has become and where it has led us. Nietzsche and Heidegger, Derrida and Rorty are just a few names. Their uneasiness mirrors widespread concern about the shape of our modern culture. As more and more begin to suspect that the road on which we have been travelling may be a dead end, attempt are made to retrace steps taken; a search begins for missed turns and for those who may have misled us. Among these Descartes has long occupied a special place as the thinker whose understanding of proper method helped found modern philosophy, science, and indeed the shape of our technological world. It is thus to be expected that attempts to question modernity, to confront it, in order perhaps to take a step beyond it, should have often taken the form of attempts to confront Descartes or Cartesian rationality. -

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions Edited by Andrew Colin Gow (Edmonton, Alberta) In cooperation with Sylvia Brown (Edmonton, Alberta) Falk Eisermann (Berlin) Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Heil (Heidelberg) Susan C. Karant-Nunn (Tucson, Arizona) Martin Kaufhold (Augsburg) Erik Kwakkel (Leiden) Jürgen Miethke (Heidelberg) Christopher Ocker (San Anselmo and Berkeley, California) Founding Editor Heiko A. Oberman † VOLUME 183 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/smrt Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Polemic and Dialogue in the Late Middle Ages Edited by Ian Christopher Levy Rita George-Tvrtković Donald F. Duclow LEIDEN | BOSTON Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder.