Work and Pensions Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridges Into Work Overview

The Bridges into Work project started in January 2009. Its aim is to support local people gain the skills and confidence to help them move towards employment. The project is part funded by the Welsh European Funding Office across 6 local authorities in Convergence areas of South Wales – Merthyr Tydfil , Rhondda Cynon Taf, Torfaen, Blaenau Gwent, Bridgend and Caerphilly. In Merthyr Tydfil the project is managed and implemented by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council, which has enjoyed massive success with its recent venture The Neighbourhood Learning Programme. It has helped to engage local people to secure full time employment and to progress onto further learning in recent years. Carrying on from the achievement is the Neighbourhood Learning Centre, Gurnos and the newly established Training Employment Centre in Treharris. Both centres seek to engage with local people from all parts of Merthyr Tydfil and fulfil the Bridges into Work objective of providing encouragement, training, advice and guidance for socially excluded people with the view to get them back into work. The Neighbourhood Learning Centre has a range of training facilities covering a variety of sectors including plumbing, painting and decorating, carpentry, bricklaying, plastering, retail, customer service and computer courses. There are a team of experienced tutors who deliver training for local people within the community. Bridges into Work successfully delivered a Pre-Employment course for Cwm Taf Health Trust to recruit Health Care Assistants. With the help and support of the Neighbourhood Learning Pre-Employment Partnership fronted by the Bridges into Work Programme which includes organisations such as Voluntary Action Merthyr Tydfil, Remploy, Working Links, Shaw Trust, A4E, JobCentre Plus and JobMatch successfully provided and supported participants interested in becoming Health Care Assistants. -

Dear Mr Kelly, Freedom of Information Request Reference Number FOI 267

Dear Mr Kelly, Freedom of Information Request reference number FOI 267 We write further to the Court of Appeal judgment in Department for Work and Pensions v Information Commissioner & Frank Zola, to which your case was joined. The judgment was handed down on Wednesday 27 July 2016. The Court of Appeal has upheld the decision of the First-tier Tribunal in Department of Work and Pensions v Information Commissioner & Frank Zola [2013]. We write, in light of the judgment, in response to your Freedom of Information request of 2012. In your request you asked for: “the names of all organizations who have provided work boost placements, work experience, or other unpaid work activity to customers of Seetec within Contract Package Area 4 (East London) within the past 12 months. In cases where a subcontractor to Seetec was involved, please note which subcontractor or subcontractors were involved with each organization.”. Contract Package Area 4 (East London) is a Work Programme Contract Package Area. Three providers deliver the Work Programme in Contract Package Area 4 (East London): Peopleplus, Shaw Trust and Seetec. You asked for the organisations that provided work placements to Seetec. DWP contracts with prime providers, such as Seetec, to source organisations who delivered the Work Programme. Some of these providers may have sent claimants on work experience placements. DWP does not contract directly with these work experience placement hosts. We have enclosed all the information we were given by Seetec in relation to your request. A copy of this letter has also been sent to the Information Commissioner’s Office. -

Work Programme Supply Chains

Work Programme Supply Chains The information contained in the table below reflects updates and changes to the Work Programme supply chains and is correct as at 30 September 2013. It is published in the interests of transparency. It is limited to those in supply chains delivering to prime providers as part of their tier 1 and 2 chains. Definitions of what these tiers incorporate vary from prime provider to prime provider. There are additional suppliers beyond these tiers who are largely to be called on to deliver one off, unique interventions in response to a particular participants needs and circumstances. The Department for Work and Pensions fully anticipate that supply chains will be dynamic, with scope to flex and evolve to reflect change within the labour market and participant needs. The Department intends to update this information at regular intervals (generally every 6 months) dependant on time and resources available. In addition to the Merlin standard, a robust process is in place for the Department to approve any supply chain changes and to ensure that the service on offer is not compromised or reduced. Comparison between the corrected March 2013 stock take and the September 2013 figures shows a net increase in the overall number of organisations in the supply chains across all sectors. The table below illustrates these changes Sector Number of organisations in the supply chain Private At 30 September 2013 - 367 compared to 351 at 31 March 2013 Public At 30 September 2013 - 128 compared to 124 at 30 March 2013 Voluntary or Community (VCS) At 30 September 2013 - 363 compared to 355 at 30 March 2013 Totals At 30 September 2013 - 858 organisations compared to 830 at March 2013. -

A Helping Hand Enhancing the Role of Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise Organisations in Employment Support Programmes in London October 2015 Appendix 1

Appendix 1 Economy Committee A Helping Hand Enhancing the role of voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations in employment support programmes in London October 2015 Appendix 1 Economy Committee Members Fiona Twycross (Chair) Labour Stephen Knight (Deputy Chair) Liberal Democrat Tony Arbour Conservative Jenny Jones Green Kit Malthouse MP Conservative Murad Qureshi Labour Dr Onkar Sahota Labour Committee contact Simon Shaw Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7983 6542 Media contact: Lisa Lam Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7983 4067 Appendix 1 Contents Chair’s foreword ................................................................................................. 1 Executive summary ............................................................................................. 2 1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 2. The challenges to VCSE organisations’ involvement in employment programmes........................................................................................................ 9 3. What can be done to address the challenges to VCSE organisations’ involvement? .................................................................................................... 14 4. Devolution of employment programmes ................................................. 21 Appendix 1 – Recommendations ...................................................................... 26 Appendix 2 – Major employment programmes .............................................. -

DWP's Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health

DWP’s Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health Related Services (Release 5 October 2020) ERSA is pleased to be able to inform you of the organisations on Tier 1 and Tier 2 of the DWP Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health Related Services (CAEHRS). In total the DWP received submissions from 61 organisations with a total of 171 compliant submissions across the 7 regional lots. Overall, this has resulted in a total of 28 organisations being awarded a place on CAEHRS, 21 of which have multiple places and 7 have single awards. As set out during this competition the design of CAEHRS allows the department to offer further places they become available. The department does not currently have any plans to undertake further activity at this time but will formally notify the market as appropriate. Those that have been unsuccessful on this occasion are able to bid for future opportunities on CAEHRS. As communicated previously CAEHRS is already planned to be used for Scotland JETS delivery in Regional Lot 7 later this month and the Long-term unemployment programme that subject to further decisions will be outlined shortly. ERSA’s Chief Executive, Elizabeth Taylor said “This announcement is welcomed by the sector. ERSA is scheduling a series of events to provide more information about the successful organisations and the DWP’s plans, these events will keep the sector informed, build partnerships, and enable collaboration”. ERSA is running a series of Meet the Primes events, the first of which will be on Friday 23 October at 1pm. This will be followed by ERSA Member Forums based on the 7 CPA/ regional lot areas. -

Tips for People Who Are Looking for Work

Tips for people who are looking for work Where to go Staff at your local Job Centre Plus will be able to help you find work, give you advice on benefits and also sign post you to organisations for support in finding a job. www.gov.uk Voluntary work Volunteering can offer so much. If you want or need to develop skills, want to see what it would be like to work in a specific area or just want to give something back to the community, voluntary work is well worth looking in to. Many local towns and cities have voluntary bureaus such as the Voluntary Skills Council. These organisations would be willing to sign post you to voluntary opportunities. Voluntary work should not affect your benefits. (please seek professional advice about this) www.do-it.org – This is a web site which offers opportunities in your area Local colleges Many local colleges run employability courses to help you get started and help you to develop the skills you need to move closer to the world of work. Local colleges have neighbourhood sites which may be in your area. They offer excellent opportunities to develop and gain new skills. www.colleges-uk.co.uk - This is a website that will help you find a college that is local to you. Work Choice Work Choice can help you get and keep a job if you have a disability or an ongoing health condition and find it hard to work. The type of support you will get depends on what you need - It’s different for everyone. -

Making Work a Real Choice Where Next for Specialist Disability Employment Support?

Making Work a Real Choice Where next for specialist disability employment support? Final Report About Shaw Trust Shaw Trust is a leading national charity with a thirty year history of supporting disabled, disadvantaged and long term unemployed people to achieve sustainable employment, independent living and social inclusion. Last year Shaw Trust delivered specialist services to over 50,000 people from 200 locations across the UK, supporting its beneficiaries to enter work and lead independent lives. In 2012 Shaw Trust merged with fellow welfare-to-work charity Careers Development Group (CDG), forming a new entity under the Shaw Trust brand. Shaw Trust is one of only two voluntary sector prime contractors of the Work Programme, operating in the London East Contract Package Area (as CDG). We further deliver services as a Work Programme subcontractor in seven different CPAs. Our extensive experience in the welfare-to-work sector includes delivery of the Work Programme’s predecessor contracts – New Deal, Pathways to Work and Flexible New Deal – as both a prime contractor and subcontractor. As the main provider of specialist disability employment programme Work Choice we deliver 16 prime contracts, six subcontracts and an additional prime contract through the special purpose vehicle CDG-WISE Ability, providing specialist support for people with disabilities, health problems and impairments across the UK. Shaw Trust also delivers direct contracts for the Skills Funding Agency, and further operates a range of social enterprises and retail shops -

A Guide for Voluntary Sector Services Working

PERFECT PARTNERS strengthening relationships within employment services supply chains. A Good Practice Guide by ERSA, ACEVO and NCVO PERFECT PARTNERS: A Good Practice Guide by ERSA, ACEVO and NCVO Published July 2012 CONTENTS. p4. Joint foreword from ERSA, ACEVO and NCVO p6. Introduction p12. Case studies: establishing supply chains p16. Case studies: managing supply chains p21. Recommendations checklist 3 JOINT FOREWORD. FROM ERSA, ACEVO AND NCVO There is a proud tradition of voluntary sector organisations supporting people into employment. Alongside public sector agencies and private provision, charities have worked to help people gain and sustain jobs, with many specialising in helping those furthest from the labour market. The recent direction of public service reform has led to a new challenging dynamic for all sectors participating in employment related services, but this is particularly the case for charities operating within the welfare to work sector. First, the adoption of the ‘prime contractor’ model for government commissioned employment related services means that fewer organisations now have a relationship directly with the commissioner. Secondly, the trend towards ‘payment by results’ has meant that only organisations of a certain size and disposition have felt able to consider acting as a prime contractor of employment related services. The result is that, in today’s world of welfare to work, the majority of voluntary sector organisations delivering publicly commissioned employment related services do so in a subcontractor capacity to a prime contractor. The challenges of this arrangement have been becoming apparent. This is why ERSA, ACEVO and NCVO are working together to encourage and support good quality relationships within supply chains. -

South East Midlands Local Enterprise Partnership European Social Fund

South East Midlands Local Enterprise Partnership European Social Fund Projects’ Directory 2014-2016 1 Contents: Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Background to the SEMLEP ESF Programme 4 3. ESF commitments to date 5 4. Funding, Outputs and Outcomes 7 5. Contracted Provision by Investment Priority: 9 5.1 Active Inclusion 10 5.2 Community-Led Local Development 32 5.3 Access to Employment 33 5.4 Young People 38 5.5 Skills for Growth 42 6. Contracted Provision by Local Authority Area 49 - Aylesbury Vale - Cherwell - Milton Keynes - Bedford - Central Bedford - South Northamptonshire - Northampton - Daventry - Kettering - Corby - Wellingborough - East Northants Annex 1 Community Grants Round 2 – provision by ward 60 2 1. Introduction Projects funded by the European Social Fund Programme (ESF) contribute to the socio- economic growth of the South-East Midlands Local Enterprise Partnership1 (SEMLEP) Area by increasing skills levels and employment rates, promoting social inclusion and combatting poverty. The ‘historical’ SEMLEP and the ‘historical’ Northamptonshire Enterprise Partnership (NEP) ESF Programmes are worth approximately £33m2and £21m respectively. Funds can be accessed by organisations from the private, public, voluntary and social enterprise sectors supporting the unemployed into work; helping young people fulfil their potential; helping those furthest from the labour market overcome barriers to entering the labour market; upskilling the workforce and encouraging Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) engage with the skills agenda. This Directory provides an overview of all the projects approved, during the first half of the European Programme3, both in the ‘historical’ SEMLEP and the ‘historical’ NEP Areas. It also provides details of what has been delivered, by which providers in every single local authority of the SEMLEP Area. -

The Work Programme: Experience of Different User Groups

House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee The Work Programme: experience of different user groups Written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published Published on 14 December 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited The Work and Pensions Committee The Work and Pensions Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Work and Pensions and its associated public bodies. Current membership Dame Anne Begg MP (Labour, Aberdeen South) (Chair) Debbie Abrahams MP (Labour, Oldham East and Saddleworth) Mr Aidan Burley MP (Conservative, Cannock Chase) Jane Ellison MP (Conservative ,Battersea) Graham Evans MP (Conservative, Weaver Vale) Sheila Gilmore MP (Labour, Edinburgh East) Glenda Jackson MP (Labour, Hampstead and Kilburn) Stephen Lloyd MP (Liberal Democrat, Eastbourne) Nigel Mills MP (Conservative, Amber Valley) Anne Marie Morris MP (Conservative , Newton Abbot) Teresa Pearce MP (Labour, Erith and Thamesmead) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the Parliament: Harriett Baldwin MP (Conservative, West Worcestershire), Andrew Bingham MP (Conservative, High Peak), Karen Bradley MP (Conservative, Staffordshire Moorlands), Ms Karen Buck MP (Labour, Westminster North), Alex Cunningham MP (Labour, Stockton North), Margaret Curran MP (Labour, Glasgow East), Richard Graham MP (Conservative, Gloucester), Kate Green MP (Labour, Stretford and Urmston), Oliver Heald MP (Conservative, North East Hertfordshire), Sajid Javid MP (Conservative, Bromsgrove), Brandon Lewis MP (Conservative, Great Yarmouth) and Shabana Mahmood MP (Labour, Birmingham, Ladywood) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

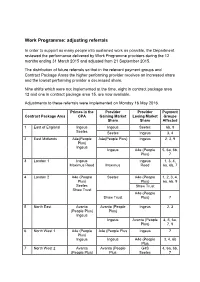

Work Programme: Adjusting Referrals

Work Programme: adjusting referrals In order to support as many people into sustained work as possible, the Department reviewed the performance delivered by Work Programme providers during the 12 months ending 31 March 2015 and adjusted from 21 September 2015. The distribution of future referrals so that in the relevant payment groups and Contract Package Areas the higher performing provider receives an increased share and the lowest performing provider a decreased share. Nine shifts which were not implemented at the time, eight in contract package area 12 and one in contract package area 15, are now available. Adjustments to these referrals were implemented on Monday 16 May 2016. Primes in the Provider Provider Payment Contract Package Area CPA Gaining Market Losing Market Groups Share Share Affected 1 East of England Ingeus Ingeus Seetec 6b, 9 Seetec Seetec Ingeus 3, 4 2 East Midlands A4e(People A4e(People Plus) Ingeus 2, 3, 9 Plus) Ingeus Ingeus A4e (People 5, 6a, 6b, Plus) 7 3 London 1 Ingeus Ingeus 1, 3, 4, Maximus Reed Maximus Reed 6a, 6b, 7 4 London 2 A4e (People Seetec A4e (People 1, 2, 3, 4, Plus) Plus) 6a, 6b, 9 Seetec Shaw Trust Shaw Trust A4e (People Shaw Trust Plus) 7 5 North East Avanta Avanta (People Ingeus 2, 3 (People Plus) Plus) Ingeus Ingeus Avanta (People 4, 5, 6a, Plus) 7, 9 6 North West 1 A4e (People A4e (People Plus Ingeus 7 Plus) Ingeus Ingeus A4e (People 3, 4, 6b Plus 7 North West 2 Avanta Avanta (People G4S 4, 6a, 6b, (People Plus) Plus Seetec 7 G4S G4S Avanta (People 1 Seetec Plus) Seetec Avanta (People 9 Plus) -

Work Programme: Adjusting Referrals

Work Programme: adjusting referrals In order to support as many people into sustained work as possible, the Department reviewed the performance delivered by Work Programme providers during the 12 months ending 31 March 2014 and adjusted from 30 March 2015 the distribution of future referrals so that in the relevant payment groups and Contract Package Areas the higher performing provider receives an increased share and the lowest performing provider a decreased share. Three shifts which were not implemented at the time, all in contract package area 12, are now available. Adjustments to these referrals were implemented on Monday 17 August 2015 Provider Provider Payment Primes in the Contract Package Area Gaining Losing Groups CPA Market Share Market Share Affected 1 East of England Ingeus Ingeus Seetec 1, 2, 3, 4, Seetec 6a, 6b, 7, 9 2 East Midlands A4e Ingeus A4e 2, 6a, 6b, 7, Ingeus 9 3 London 1 Ingeus Ingeus Maximus 4 Maximus Reed 6a, 7 Reed Reed Maximus 3 Ingeus 6b 4 London 2 A4e Shaw Trust Seetec 1, 3, 7 Seetec A4e 4, 6b Shaw Trust Seetec Shaw Trust 6a A4e 9 5 North East Avanta Ingeus Avanta 1, 6a, 6b, 7 Ingeus Avanta Ingeus 4 6 North West 1 A4e Ingeus A4e 3, 4, 6a, 6b Ingeus 7 North West 2 Avanta Avanta Seetec 2, 4, 6a, 9 G4S G4S Seetec 3 Seetec Avanta 7 Seetec G4S 6b Avanta 9 8 Scotland Ingeus Ingeus Working Links 4, 5, 6b, 7 Working Links 9 South East 1 A4e Maximus A4e 2, 3, 4, 6a, Maximus 6b, 7, 9 10 South East 2 Avanta Avanta G4S 4, 6b G4S G4S Avanta 7 11 South West 1 Prospects Working Links Prospects 1, 3, 6a Working Links Prospects