Churchguide.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seaside Resorts of Westmorland and Lancashire North of the Sands in the Nineteenth Century

THE SEASIDE RESORTS OF WESTMORLAND AND LANCASHIRE NORTH OF THE SANDS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY BY ALAN HARRIS, M.A., PH.D. READ 19 APRIL 1962 HIS paper is concerned with the development of a group of Tseaside resorts situated along the northern and north-eastern sides of Morecambe Bay. Grange-over-Sands, with a population in 1961 of 3,117, is the largest member of the group. The others are villages, whose relatively small resident population is augmented by visitors during the summer months. Although several of these villages have grown considerably in recent years, none has yet attained a population of more than approxi mately 1,600. Walney Island is, of course, exceptional. Since the suburbs of Barrow invaded the island, its population has risen to almost 10,000. Though small, the resorts have an interesting history. All were affected, though not to the same extent, by the construction of railways after 1846, and in all of them the legacy of the nineteenth century is still very much in evidence. There are, however, some visible remains and much documentary evidence of an older phase of resort development, which preceded by several decades the construction of the local railways. This earlier phase was important in a number of ways. It initiated changes in what were then small communities of farmers, wood-workers and fishermen, and by the early years of the nineteenth century old cottages and farmsteads were already being modified to cater for the needs of summer visitors. During the early phase of development a handful of old villages and hamlets became known to a select few. -

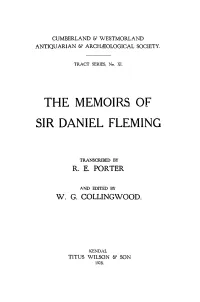

William Le Fleming, Richard Le Fleming &C

CUMBERLAND & WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN & ARCHJEOLOGICAL SOCIETY. TRACT SERIES, No. XI. THE MEMOIRS OF SIR DANIEL FLEMING TRANSCRIBED BY R. E. PORTER AND EDITED BY W. G. COLLINGWOOD. KENDAL TITUS WILSON & SON 1928. KENDAL: PRINTED BY TITUS WILSON & SON, 28, Highgate. 1928. CONTENTS. PAGE... Editor's Preface Vll Sir Daniel Fleming, from the portrait at Rydal Hall . to /ace I The Earls of Flanders and the Flemings .. I Michael le Fleming of Furness .. 5 William f. Michael le Fleming and his family II Richard f. Michael le Fleming and the family of Beckermet . Richard f. John le Fleming and the family at Coniston and Beckermet . Thomas f. Thomas Fleming and the family at • Rydal and Coniston . 37 The Flemings of Conistori, Rydal and Skirwith · ... 56 William f. John Fleming, 1628-1649 .. 64 Daniel Fleming of Skirwith and his family 66 Sir Daniel Fleming, his autobiography 73 Description of Caernarvon Castle 81 Gleaston Castle .. 82 Coniston . 82 Rydal . 85 The arms belonging to the family of Fleming ~9 Sir Daniel Fleming's advice to his son 92 Appendix I ; Beckermet documents 98 Appendix II; Rydal documents .. I03 Appendix III ; Kirkland documents . Il2 Index . II8 EDITOR'S PREFACE. Our Society has already printed, in the Tract Series of which this volume is the latest, two short works by Sir Daniel Fleming of Rydal, his Surveys of Cumberland and of Westmorland. These Memoirs were long lost, and his own manuscript, if there was such in any complete form, is still unknown; but an early copy was found and transcribed by Mr. R. E. Porter, and with the leave of Stanley Hughes le Fleming Esq., of Rydal Hall, is now printed. -

Meeting of Urswick Parish Council

1094 MINUTES OF URSWICK, BARDSEA AND STAINTON PARISH COUNCIL From the meeting held on Thursday 20th April 2017 Urswick Parish Room, 7.30pm Present: Cllr. L. Birchall, Cllr. P. Bolt, Cllr. D. Chamberlain, Cllr. J. Keen (Chairman), Cllr. M. Turner, Dr. P. Attree (Clerk). District and County councillors: J. Willis. Members of the public: 1 1. To receive and approve apologies for absence. Apologies for absence were received from Cllrs. N. Cowsill, J. Hannah & J. Winder. Cllr. Bolt gave apologies for his late arrival. RESOLVED: that the apologies be noted and the reasons noted. 2. Declarations of interests To receive declarations by elected and co-opted members of interests in respect of items on this agenda. None. 3. Requests for dispensations None. 4. To authorise the Chairman to sign as a correct record the minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 9th March 2017. RESOLVED: that the minutes of the meeting held on 9th March 2017 be signed by the Chairman as a true record. 5. To note progress on matters not on today’s agenda – for report and observation only (items requiring a decision to be placed on agenda of next meeting). The Clerk reported on the following: • Nuisance smell from sileage stored at land adjacent to Daisy Hill Cottage, Great Urswick - reported to Public Protection Team and logged. • Potholes on lanes used as alternative routes during roadworks at Lindal in Furness. • Site of the former Coot, Great Urswick. Untidy site reported to District Council, and obstruction to traffic sightlines reported to County Highways. • Ongoing enquiries regarding Greenbank Gardens site, Little Urswick. -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

Appendix 3 Objections.Pdf

Prof. Jim D. Marshall Earth, Ocean and Ecological Sciences School of Environmental Sciences University of Liverpool 4 Brownlow Street Liverpool L69 3GP United Kingdom 0151--794 5177 Commons Registration Authority Cumbria County Council Application CA13/22 9 February 2019 To whom it may concern Urswick Tarn - Retention of Common Land Status. I am writing this letter to oppose application CA13/22 which seeks to remove the common land status assigned to the land associated with the former chapel at Urswick Tarn. My research group and I have long standing interests in Urswick Tarn and other marl lakes in Northwest England and have published many papers in international scientific journals on the significance of the sediment records that are preserved there. Starting with the work of Professor Frank Oldfield in the 1950’s and 60’s Urswick Tarn and its surrounding marl bench has been studied by scientists from Liverpool and many other Universities (including Exeter, Edge Hill and King’s College London). This is a site of national and indeed international scientific importance. The marl sediments beneath the chapel land and in the lake basin record the changing vegetation, land use and climate of the site spanning the 10,000 years and more since the end of the last glaciation. Marl lakes of this sort are relatively rare and provide a unique combination of biological remains and chemical markers than can be used to reconstruct past environmental change. My own specialisation, oxygen and carbon stable isotope geochemistry, enable us to quantitatively reconstruct past changes in temperature, rainfall and carbon cycling. -

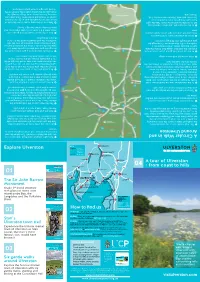

04 Tour of Ulverston

www.ulverstoncouncil.org.uk visitulverston.com www.visitulverston.com ending at the Coronation Hall Coronation the at ending changes, errors or omissions, or any inconvenience arising therefrom. arising inconvenience any or omissions, or errors changes, gentle walks, starting and and starting walks, gentle going to press, Ulverston Town Council cannot accept any responsibility for any any for responsibility any accept cannot Council Town Ulverston press, to going town of Ulverston with six six with Ulverston of town Whilst every effort was made to ensure that information was correct at time of of time at correct was information that ensure to made was effort every Whilst Explore the historic market market historic the Explore and mountains and • Fairtrade Town Fairtrade a a Respect the countryside the Respect ULVERSTON Proud to be be to Proud around Ulverston around • surrounding fells fells surrounding Protect wildlife, plants and trees and plants wildlife, Protect 2016 • Partnership Partnership Bay and the the and Bay Safeguard water supplies water Safeguard Six gentle walks gentle Six Community Community & keep to paths across farmland across paths to keep & of Morecambe Morecambe of & Ulverston Ulverston & • Avoid damaging fences, hedges hedges fences, damaging Avoid Town Council Council Town extensive views views extensive © Ulverston Ulverston © • Keep dogs under proper control proper under dogs Keep 03 Ulverston with with Ulverston • Leave all gates as you find them find you as gates all Leave walk around around walk • Guard against the risk of fire of risk the against Guard • 11 mile circular circular mile 11 Leave no litter no Leave PLEASE REMEMBER PLEASE known it known www.visitulverston.com to go please events, or accommodation famous son, would have have would son, famous For enquiries about transport, booking booking transport, about enquiries For FURTHER INFORMATION INFORMATION FURTHER Laurel, the town’s most most town’s the Laurel, cost 10p plus network extras. -

Urswick Parish Plan 2006

'" U-rswick PC1-rish Ncrl::ul"e's hand blessed this pal"ish with a beautLl and chamctel" which few can l"ival. Good fortune then favoul"ed us with fOl"ebeal"s whose cal"ing hand - and fol" ~ a few, with the ultimate saC1"ifice- .J ~I I passed on to us the splendoul" .. f I that we now shal"e. Let us not be found wanting in OUl"l"espect fol" what those who I went befol"e have left: behind, 01"in OUl"dutLl to those who will succeed us. MaLI theLl in theil" tU1"nl"evel"e it as a home, which compels theil" affection, and is worthLl of theil" ca1"e. .J1£//\Y)! f,~ ~ (/h"fii ) :J'Y"') ~ .I.{f G...J_~J/f URSWICK PARISH PLAN EDITION 1 2006 Contents I Introduction I 2 Spiritual Expression and Development 4 3 Listed Buildings in the Parish 5 4 Educating the Junior Citizens of the Parish 6 5 Employment in the Parish 6 6 Services IIIthe Parish 8 7 Parish Amenities 9 8 Community Groups and Associations 10 9 Surveys of Parish Residents' Concerns and Aspirations 12 10 ConcernsandActionPlans- Parishwideitems 14 11 ConcernsandActionPlans- Bardsea items 19 12 Concerns and Action Plans - Urswick villages items 22 13 ConcernsandActionPlans- StaintonwithAdgarleyitems 25 14 Acknowledgements 27 OISWICI PARISHPLAN 1 Introduction Located to the east of the A590 trunk road on the Furness Peninsula in Cumbria, the border of Urswick Parish is 1.7 miles south of Ulverston town centre and 3.4 miles north of Barrow in Furness town centre. -

Gleaston Castle, Gleaston, Cumbria Results of Aerial Survey And

Gleaston Castle, Gleaston, Cumbria Results of Aerial Survey and Conservation Statement Helen Evans and Daniel Elsworth April 2016 Gleaston Castle: Aerial Survey and Conservation Statement 1 Summary Gleaston Castle is located on the Furness Peninsula, South Cumbria and is a fortified manor in the form of a courtyard or enclosure castle. The site, now ruinous, originally consisted of a large hall and three towers joined by a substantial curtain wall. The castle may have been constructed in the early 14th Century when Cumbria was subject to raids from Scotland under Robert the Bruce, although there is not necessarily any direct connection to these events, especially given that it is not mentioned in documentary sources before 1350. After a relatively short period as a manorial residence the site was abandoned in the mid-15th Century and recorded as a ruin in the mid-16th Century. Despite the attentions of antiquarians, the history and remains of Gleaston Castle are poorly understood. It has never been fully recorded and required a detailed archaeological survey to better understand its significance and inform future conservation strategies. Elements of the ruinous remains of the castle are in a dangerous structural condition requiring extensive repair and consolidation to make them safe. For this reason the site, immediately adjacent to a public road, is not publically accessible. Gleaston Castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and a Grade 1 listed building. Presently there is no coherent management structure in place or funds available for its conservation. Although the castle has significant historical, archaeological and tourism potential, the present complexities of its situation have led to a lack of intervention. -

Local Plan (2006)

& Alterations (Final Composite Plan) This document combines the South Lakeland Local Plan (adopted in 1997) and the Alterations to the Local Plan (adopted in March 2006) Lawrence Conway Strategic Director Customer Services Published September 2007 he South Lakeland Local Plan and Alterations (Final Composite Plan) T March 2007) brings together in a single document: • the South Lakeland Local Plan, adopted in 1997 • the Alterations to the Local Plan, adopted in March 2006 All three documents and further information on the Local Plan can be viewed or downloaded from the Council's website at www.southlakeland.gov.uk/planning This combined document brings together the relevant polices and supporting text from both the South Lakeland Local Plan and Local Plan Alterations for the convenience of readers, who previously had to refer to two separate documents. PREFACE It is important to note that the Council has not amended the contents of either document - both of which contain references, which while correct at the time of PREFACE their respective adoptions, but may now be dated. The Local Plan policies and text which have been added or altered (in whole or part) through the Local Plan Alterations are shown within grey shaded boxes. The Development Plan The South Lakeland Local Plan and Alterations to the Local Plan form part of the statutory Development Plan for South Lakeland District, outside the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales National Parks. It sets out land use policies to guide new development through granting of planning permission. The Development Plan also comprises the Cumbria and Lake District Joint Structure Plan, adopted in April 2006. -

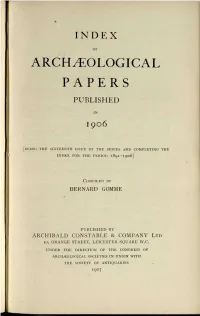

Index of Archaeological Papers Published in 1906

INDEX OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PAPERS PUBLISHED IN I9O6 [BEING THE SIXTEENTH ISSUE OF THE SERIES AND COMPLETING THK INDEX FOR THE PERIOD 1891-1906] COMPILED BY BERNARD GOMME PUBLISHED BY ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & COMPANY LTD 10, ORANGE STREET, LEICESTER SQUARE W.C. UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES IN UNION WITH THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES 1907 CONTENTS [Those Transactions for the first time inchidcd in the index are marked with an asterisk,* the others are continuations from the indexes of 1891 1902. Transactions included for the first time are indexed from 1891 onwards.] Anthropological Institute, Journal, vol. xxxvi. (NS. ix.). Antiquaries, Ireland, Proceedings of Royal Society, 5th S. vol. xvi. Antiquaries, London, Proceedings of Royal Society, 2nd S. vol. xxi. pt. 1. (to p. 230). Antiquaries, Scotland, Proceedings of Society, vol. xl, Arehaeologia, vol. Ix. pt. 1. Archtuologia ^Eliana, 3rd S. vol. ii. Archaeologia Cambr^nsis, Gth S. vol. vi. Archaeological Institute, Journal, vol. Ixiii. jBarrow Naturalists' Field Club, Transactions, vols. i., iii.,iii. (No. 2), iv.,v., ix., xiv. Berks, Bucks and Oxfordshire Archaeological Journal, vols. xi., xii. pts. 1, 2 and 3 (to p. 96). Biblical Archaeology, Society of, Proceedings, vol. xxviii. Birmingham and Midland Institute, Transactions, vol. xxxi. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Transactions, vol. xxviii. pt. 2., xxix. (to p. 204). British Archaeological Association, Journal, N.S.. vol. xii. British Architects, Royal Institute of, Journal, 3rd S. vol. xiii. British Numismatic Journal, 1st S. vol. ii. *British School at Athens, Annual, vols. i., ii., iii., iv., v., vi., vii., viii., ix., x.,xi. *British School at Rome, Papers, vols. -

Cumbria Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessment

Cumbria Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessment for Allerdale Borough Council, Barrow Borough Council, Carlisle City Council, Copeland Borough Council, Cumbria County Council, Eden District Council, Lake District National Park Authority, and South Lakeland District Council Final Report November 2013 Main Contact: Michael Bullock arc4 Ltd Email: [email protected] Website: www.arc4.co.uk ©2013 arc4 Limited (Company No. 06205180) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 7 Study Components .......................................................................................................... 8 Phase 1: Literature/desktop review and stakeholder discussions .................................... 9 Phase 2: Survey of Gypsies and Travellers across Cumbria ........................................... 9 Phase 3: Production of report .......................................................................................... 9 2. Methodology ....................................................................................................... 11 3. Legislative and Policy Context ............................................................................ 14 Legislative background .................................................................................................. 14 Policy background ......................................................................................................... 14 CLG Design Guidance .................................................................................................. -

Consultation Statement June 2021

South Lakeland Local Plan Review: Consultation Statement June 2021 www.southlakeland.gov.uk Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Purpose of this document ..................................................................................... 4 1.2 South Lakeland Local Plan Review....................................................................... 4 Context ....................................................................................................................... 4 The timeline for the Local Plan Review ...................................................................... 5 2. Overall approach to consultation and engagement ..................................................... 7 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Engagement Methods ........................................................................................... 7 3. Early Engagement – February to September 2020 ................................................... 10 3.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 10 3.2 How did we engage? .......................................................................................... 10 3.3 How did people respond, and how many people responded .............................. 14 Who responded?..........................................................................................................