Reflections on Resilience in the Karamoja Cluster Over 40 Years Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Electoral Commission

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION Telephone: +256-41-337500/337508-11 Plot 55 Jinja Road Fax: +256-31-262207/41-337595/6 P. O. Box 22678 Kampala, Uganda E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ec.or.ug th Ref: ………………………………………Adm72/01 Date: ....9 ......................................... July 2019 Press Statement Programme for Elections of Interim Chairpersons in the Seven Newly-created Districts The Electoral Commission informs the general public that the following seven (7) newly- created districts came into effect on 1st July 2019: 1. Madi-Okollo District, which has been created out of Arua District; 2. Karenga District, which has been created out of Kaabong District; 3. Kalaki District, which has been created out of Kaberamaido District; 4. Kitagwenda District, which has been created out of Kamwenge District; 5. Kazo District, which has been created out of Kiruhura District; 6. Rwampara District, which has been created out of Mbarara District; and, 7. Obongi District, which has been created out of Moyo District. Accordingly, the Electoral Commission has appointed Thursday, 25th July, 2019 as the polling day for Elections of Interim District Chairperson in the above seven newly- created districts. Voting shall be by Electoral College and secret ballot and will be conducted at the headquarters of the respective new district, starting at 9:00am. The Electoral College shall comprise District Directly Elected Councillors and District Women Councillors representing the electoral areas forming the new districts. Please note that the elections of District Woman Representative to Parliament in the above newly-created districts will be conducted in due course. -

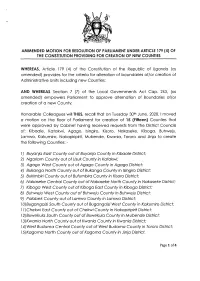

(4) of the Constitution Providing for Creation of New Counties

AMMENDED MOTTON FOR RESOLUTTON OF PARLTAMENT UNDER ARTTCLE 179 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION PROVIDING FOR CREATION OF NEW COUNTIES WHEREAS, Ariicle 179 (a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ugondo (os omended) provides for the criterio for olterotion of boundories oflor creotion of Administrotive Units including new Counties; AND WHEREAS Section 7 (7) of the Locql Governments Act Cop. 243, (os omended) empowers Porlioment to opprove olternotion of Boundories of/or creotion of o new County; Honoroble Colleogues willTHUS, recoll thot on Tuesdoy 30rn June, 2020,1 moved o motion on the floor of Porlioment for creotion of I5 (Fitteen) Counties thot were opproved by Cobinet hoving received requests from the District Councils of; Kiboole, Kotokwi, Agogo, lsingiro, Kisoro, Nokoseke, Kibogo, Buhweju, Lomwo, Kokumiro, Nokopiripirit, Mubende, Kwonio, Tororo ond Jinjo to creote the following Counties: - l) Buyanja Eost County out of Buyanjo County in Kibaale Distric[ 2) Ngoriom Covnty out of Usuk County in Kotakwi; 3) Agago Wesf County out of Agogo County in Agogo District; 4) Bukonga Norfh County out of Bukongo County in lsingiro District; 5) Bukimbiri County out of Bufumbira County in Kisoro District; 6) Nokoseke Centrol County out of Nokoseke Norfh County in Nokoseke Disfricf 7) Kibogo Wesf County out of Kibogo Eost County in Kbogo District; B) Buhweju West County aut of Buhweju County in Buhweju District; 9) Palobek County out of Lamwo County in Lamwo District; lA)BugongoiziSouth County out of BugongoiziWest County in Kokumiro Districf; I l)Chekwi Eosf County out of Chekwi County in Nokopiripirit District; l2)Buweku/o Soufh County out of Buweku/o County in Mubende Disfricf, l3)Kwanio Norfh County out of Kwonio Counfy in Kwonio Dislricf l )West Budomo Central County out of Wesf Budomo County inTororo Districf; l5)Kogomo Norfh County out of Kogomo County in Jinjo Districf. -

Emergency Health Fiscal and Growth Stabilization and Development

LIST OF COVID-19 QUARANTINE CENTRES IN WATER AND POWER UTILITIES OPERATION AREAS WATER S/N QUARANTINE CENTRE LOCATION POWER UTILITY UTILITY 1 MASAFU GENERAL HOSPITAL BUSIA UWS-E UMEME LTD 2 BUSWALE SECONDARY SCHOOL NAMAYINGO UWS-E UMEME LTD 3 KATAKWI ISOLATION CENTRE KATAKWI UWS-E UMEME LTD 4 BUKWO HC IV BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 5 AMANANG SECONDARY SCHOOL BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 6 BUKIGAI HC III BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 7 BULUCHEKE SECONDARY SCHOOL BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 8 KATIKIT P/S-AMUDAT DISTRICT KATIKIT UWS-K UEDCL 9 NAMALU P/S- NAKAPIRIPIRIT DISTRICT NAMALU UWS-K UEDCL 10 ARENGESIEP S.S-NABILATUK DISTRICT ARENGESIEP UWS-K UEDCL 11 ABIM S.S- ABIM DISTRICT ABIM UWS-K UEDCL 12 KARENGA GIRLS P/S-KARENGA DISTRICT KARENGA UWS-K UMEME LTD 13 NAKAPELIMORU P/S- KOTIDO DISTRICT NAKAPELIMORU UWS-K UEDCL KOBULIN VOCATIONAL TRAINING CENTER- 14 NAPAK UWS-K UEDCL NAPAK DISTRICT 15 NADUNGET HCIII -MOROTO DISTRICT NADUNGET UWS-K UEDCL 16 AMOLATAR SS AMOLATAR UWS-N UEDCL 17 OYAM OYAM UWS-N UMEME LTD 18 PADIBE IN LAMWO DISTRICT LAMWO UWS-N UMEME LTD 19 OPIT IN OMORO OMORO UWS-N UMEME LTD 20 PABBO SS IN AMURU AMURU UWS-N UEDCL 21 DOUGLAS VILLA HOSTELS MAKERERE NWSC UMEME LTD 22 OLIMPIA HOSTEL KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD 23 LUTAYA GEOFREY NAJJANANKUMBI NWSC UMEME LTD 24 SEKYETE SHEM KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD PLOT 27 BLKS A-F AKII 25 THE EMIN PASHA HOTEL NWSC UMEME LTD BUA RD 26 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD 27 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIGOWA NTINDA NWSC UMEME LTD 28 MARIUM S SANTA KYEYUNE KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD JINJA SCHOOL OF NURSING AND CLIVE ROAD JINJA 29 MIDWIFERY A/C UNDER MIN.OF P.O.BOX 43, JINJA, NWSC UMEME LTD EDUCATION& SPORTS UGANDA BUGONGA ROAD FTI 30 MAAIF(FISHERIES TRAINING INSTITUTE) NWSC UMEME LTD SCHOOL PLOT 4 GOWERS 31 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 2 GOWERS 32 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 45/47 CHURCH 33 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD RD CENTRAL I INSTITUTE OF SURVEY & LAND PLOT B 2-5 STEVEN 34 NWSC 0 MANAGEMENT KABUYE CLOSE 35 SURVEY TRAINING SCHOOL GOWERS PARK NWSC 0 DIVISION B - 36 DR. -

Addendum 1 and 2 for Fy 2Ol9|2O

a 1J6J BUDGET COMMITTEE AMENDMENTS h^N TO THE REPORT OF'THE BUDGET COMMITTEE ON THE SUPPLEMENTARY EXPENDITURE SCHEDULE NO.2: ADDENDUM 1 AND 2 FOR FY 2OL9|2O .l I (' 6.0 RECURRENT SUPPLEMENTARY ESTIMATES RECOMMENDED FOR PRIOR APPROVAL AND SUPPLY UNDER SCHEDULE 2z ADDENDUM 1 & 2 FY 2Or9l20 The committee has noted the inflow of new resources in form of Donations from different Development Partners, Private Sector and other well-wishers. For purposes of harrnonizing and rationalizing resource utilization in the fight against the COVlD-pandemic, the Committee recommends that all such donations be channeled through the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development. The Committee recommends that the Supplementary Expenditure requests for the Votes specified in Annex 1 & 2 be approved and supplied. The summary is as follows: Summary of sums to be supplied Addendum (No.1) Shs Addendum (No.2l Shs TOTAL rf RECURRENT 203,609,369,305 207,780,760,6t4 * 41 1.390. t29.9r9 DEVELOPMENT 4s5,269,323,000 66,219,239,386 501.488.562.386 TOTAL 639,978,692,305 274,OOO,OOO,OOO 9L2.A74.692.305 STATUTORY 9,886,705,208 10,000,000,000 tA 19,886,705,208 GRAND TOTAL 648.765,397,513 2g4,OOO,OOO,OOO 932,765,397,513 The committee further requests the House to adopt the report of the Committee Rt. Hon. Speaker, I beg to move '{w\ 13 ANNEX 1: Supplementary Expenditure Schedule 2 Addendum 1 - r.Y2OLgl2O Vote Total (Ushsf 001 Office of the President 1.465.160.000 1,465.160,000 Ministry of Defence and 004 Veteran Affairs 58.363.557.128 400,000,000,000 458,363,557.r28 -

USAID-PACT-Karamoja-Success

USAID Program for Accelerated Control of TB in Karamoja SUCCESS STORIES DISCLAIMER: USAID PACT-Karamoja made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this storybook are the responsibility of IDI and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. About PACT-Karamoja Where We Work Period: 2020 - 2025 Funder Project Goal Scale-up evidence-based and high-impact interventions towards the achievement of End TB strategy targets of 90% treatment coverage and treatment success through health system strengthening in all districts of the Karamoja sub-region. Project Objectives Improve treatment success rates to 90% Improve case detection rates to 85% Improve cure rates to at least 70% Our Partners The USAID Program for Accelerated Control of TB in Karamoja (PACT Karamoja) is implemented by the Infectious Diseases Institute Ltd (IDI) with its partner: Dr. Achar, District Health Officer Kotido district receiving one of motor bikes donated by the Project from Chief of Party, USAID PACT-Karamoja. USAID Support Improved TB Patient Tracking Among Nomadic Populations in Karamoja Sub-region Ruto, however, did not give up on finding Margaret. He continued to check if Margaret had returned to her home whenever he visited other TB patients in Kukayim village for adherence support. He also regularly called her next of kin to find out if Margaret had returned from Ochorichor village. After five months of tracking Margaret, Ruto found her back at her home unwell. He encouraged her to return to Amudat hospital for review by the health workers. -

UGANDA - KARAMOJA IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS OVERVIEW of the IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS FEBRUARY 2021 - JANUARY 2022 of KARAMOJA Issued July 2021

UGANDA - KARAMOJA IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS OVERVIEW OF THE IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS FEBRUARY 2021 - JANUARY 2022 OF KARAMOJA Issued July 2021 KEY FIGURES FEBRUARY 2021 - JANUARY 2022 Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) 10,257 56,560 Moderate Acute cases of children aged Malnutrition (MAM) 6-59 months acutely 46,303 malnourished 10,208 IN NEED OF TREATMENT cases of pregnant or lactating women acutely malnourished IN NEED OF TREATMENT Current AMN February - July 2021 Overview How Severe, How Many and When: According to the latest IPC Acute Malnutrition (AMN) analysis, during the lean season of 2021, February – July 2021, of the nine districts in Karamoja region, one district has Critical levels of acute malnutrition (IPC AMN Phase 4), four districts have Serious levels of acute malnutrition (IPC AMN Phase 3) and another four districts have Alert levels of 1 - Acceptable 5 - Extremely critical Map Symbols Evidence Level acute malnutrition (IPC AMN PhaseAcceptable 2). About 56,600 children in the nine districts Phase classification Urban settlement * 2 - Alert based on MUAC classification ** Medium included in the analysis are affectedHigh by acute malnutrition and are in need of 3 - Serious Areas with inadequate *** evidence IDPs/other settlements Scarce evidence due treatment. Approximatelyclassification 46,300to childrenlimited or no are moderately malnourished while 4 - Critical Areas not analysedover 10,200 children are severelyhumanitarian malnourished. access Around 10,200 pregnant or 1 - Acceptable 5 - Extremely critical Map Symbols Evidence Level lactating women areAcceptable also acute malnourished. Phase classification Urban settlement * 2 - Alert based on MUAC classification ** Medium High 3 - Serious Areas with inadequate Where: Kaabong*** district has Critical levels of acute malnutrition (IPC AMN Phase evidence IDPs/other settlements Scarce evidence due classification4) with a Global Acuteto limited Malnutrition or no (GAM) prevalence of 18.6%. -

Women's Peace and Humanitarian Fund

Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT TEMPLATE Country Submitted by PUNO(s) UN Women or NUNO(s)1 Uganda Name of Entity: UN Women Name of Representative: Dr Maxime Houinato MPTF Project Number Implementing Partners 121715 List all the CSOs supported by the WPHF for every project (if joint project, please list lead CSO as well as all CSOs Reporting Period receiving a grant through the lead CSO). July 2020 – December 2021 1. Coalition for Action on 1325 (CoACT 1325) Funding Call Select all that apply with Teso Karamoja Women Initiative for Peace (TEKWIP), Human Rights Democracy Link Africa (RIDE Africa) and Karambi Action for Life improvement (KALI). 2. Extend a Life Initiative Uganda (ELI) 3. Slum Aid Project (SAP) with Centre for Justice ☐ Regular Funding Cycle and Strategic Innovations (CJSI) and Sonke Gender Justice (SGJ) Specify Call (Round 1, 2, 3, etc.) ________ 4. Teso Women Peace Activists (TEWPA) ☒ Spotlight WPHF Partnership 5. Uganda Change Agent Association (UCAA) Call 1 with Kaabong People Living with AIDS ☐ COVID-19 Emergency Response Window (KAPLAS) 6. Umbrella of Hope Initiative (UHOPI) 7. Uganda Women's Network (UWONET) 8. Women's International Peace Center (WIPC) 9. Women's Organisation Network for Human Rights Advocacy (WONETHA) WPHF Outcomes2 to which report contributes Project Locations for reporting period ☐ Outcome 1: Enabling environment for Northern Region: Gulu, Kitugum implementation of WPS commitments West Nile: Adjumani, Arua ☐ Outcome 2: Conflict prevention Karamoja: Karamoja, Kaboong ☐ -

The Ifms Journey 2003 - 2020

MINISTRY OF FINANCE PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ACCOUNTANT GENERAL’S OFFICE THE IFMS JOURNEY 2003 - 2020 Document Control Version Author / Updated Reviewed by Reviewed by Date 1.0 Rogers Baguma Aiden Rujumba - April 2020 Commissioner, FMSD 1.1 Rogers Baguma Aiden Rujumba Godfrey Ssemugooma May 2020 Commissioner, FMSD Director, FMSD 1.2 Rogers Baguma Aiden Rujumba Godfrey Ssemugooma June 2020 Commissioner, FMSD Director, FMSD Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 9 1.1 IFMS .................................................................................................................................... 9 1.1.1 The Integrated Financial Management System ..................................................................................................... 9 2 IFMS OPERATION ............................................................................. 11 2.1 IFMS MODULES ............................................................................................................... 11 2.2 IFMS DATA LINKS ........................................................................................................... 11 3 BRINGING UP AN IFMS SITE ........................................................... 13 3.1 PRE-REQUISITES FOR IFMS ............................................................................................ 13 3.1.1 Infrastructure Readiness ........................................................................................................................................ -

Link Nca Nutrition Causal Analysis Karamoja, Mid-Northern and West Nile Sub-Regions, Uganda

LINK NCA NUTRITION CAUSAL ANALYSIS KARAMOJA, MID-NORTHERN AND WEST NILE SUB-REGIONS, UGANDA a b LINK NCA NUTRITION CAUSAL ANALYSIS KARAMOJA, MID-NORTHERN AND WEST NILE SUB-REGIONS, UGANDA Office of the Prime Minister Kampala, Uganda UNICEF Uganda Kampala, Uganda Action Against Hunger, Uganda Kampala, Uganda June 2020 i The publication is a part of the EU-UNICEF Joint Nutrition Action under the Development Initiative for Northern Uganda (DINU) of the United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF). Required citation: Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), UNICEF Uganda and Action Against Hunger (AAH) Uganda. 2020. Link Nutrition Causal Analysis for Karamoja, Mid-Northern and West Nile Sub-Regions, Uganda. Kampala, Uganda This work is a product of the staff of Action Against Hunger Uganda with external technical contributions from Action Against Hunger US/HEARO and AAH UK. Funding for the survey was provided by the European Union (EU) and UNICEF. The study was done under the overall supervision of the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) of the Government of Uganda. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of Head Office of Action Against Hunger or the other countries where they operate. Much as the authors guarantee the accuracy of the qualitative data included in this work, we do not guarantee the accuracy of the quantitative data. The work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for non-commercial purposes as long as full attribution is given. Any queries on this work should be addressed to: The Country Director, Action Against Hunger, Uganda Office Embassy Plaza, off Nsambya-Kabalagala road. -

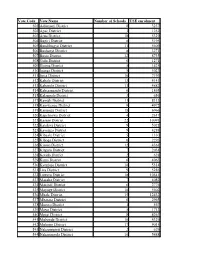

Vote Code Vote Name Number of Schools USE Enrolment 501

Vote Code Vote Name Number of Schools USE enrolment 501 Adjumani District 8 3237 502 Apac District 3 1252 503 Arua District 18 5329 504 Bugiri District 8 5195 505 Bundibugyo District 11 5609 506 Bushenyi District 8 3271 507 Busia District 12 8735 508 Gulu District 6 1271 509 Hoima District 5 1425 510 Iganga District 5 5023 511 Jinja District 10 7193 512 Kabale District 13 4143 513 Kabarole District 11 4882 514 Kaberamaido District 6 1865 515 Kalangala District 3 656 517 Kamuli District 11 8313 518 Kamwenge District 9 4972 519 Kanungu District 18 6966 520 Kapchorwa District 4 2617 521 Kasese District 22 10091 522 Katakwi District 9 5021 523 Kayunga District 9 4288 524 Kibaale District 5 1330 525 Kiboga District 6 2293 526 Kisoro District 12 4361 527 Kitgum District 7 2034 528 Kotido District 2 628 529 Kumi District 6 4063 530 Kyenjojo District 10 5314 531 Lira District 9 5286 532 Luwero District 18 10541 533 Masaka District 7 4082 534 Masindi District 6 2776 535 Mayuge District 10 5602 536 Mbale District 15 12432 537 Mbarara District 6 2965 538 Moroto District 1 567 539 Moyo District 5 1713 540 Mpigi District 8 4263 541 Mubende District 10 4329 542 Mukono District 17 9015 543 Nakapiripirit District 2 629 544 Nakasongola District 10 5488 545 Nebbi District 5 2257 546 Ntungamo District 18 8412 547 Pader District 8 2856 548 Pallisa District 8 6661 549 Rakai District 14 7586 550 Rukungiri District 21 11111 551 Sembabule District 8 4162 552 Sironko District 10 5552 553 Soroti District 5 3421 554 Tororo District 17 13341 555 Wakiso District 14 -

UWEP) Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development Simbamanyo House, Plot 2, George Street

BUSINESS & TENDERS UGANDA WOMEN ENTREPRENEURSHIP PROGRAMME (UWEP) Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development Simbamanyo House, Plot 2, George Street. P.O Box 7136, Kampala Tel: 041-4 343572/ 0414 699219/ 0414 699220, Facebook: @uwep.mglsd ON THE OCCASION TO MARK THE International Women’s Day, 2021 H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni HON. Frank K. Tumwebaze HON. Mutuuzo Peace Regis Aggrey David Kibenge Winifred Komuhangi Masiko THE PRESIDENT OF THE MINISTER OF GENDER, LABOUR MINISTER OF STATE FOR PERMANENT SECRETARY National Programme REPUBLIC OF UGANDA AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT GENDER AND CULTURE Coordinator - UWEP Programme Background: h) The group approach has given Women an opportunity to improve Over the years, majority of women in Uganda have been disenfranchised knowledge and skill through mentoring each other. The greater from the formal business sector due to limited access to affordable involvement of the Women in mobilization, sensitization, prioritization credit, limited technical knowledge on business entrepreneurship and and planning for their needs, implementation and monitoring and management, limited access to markets as well as information regarding evaluation of Programme activities has created a sense of business opportunities. To address that problem, Government of Uganda empowerment and confidence to take charge of their destiny. in the FY 2015/2016 initiated the Uganda Women Entrepreneurship Programme (UWEP) with a core goal of empowering Ugandan women to improve their income levels and their contribution to economic -

Ministry of Finance, Planning & Economic Development

Telephone : 256 41 4707 000 : 256 41 4232 095 Ministry Of Finance, Planning Fax : 256 41 4230 163 : 256 41 4343 023 & Economic Development : 256 41 4341 286 Plot 2-12, Apollo Kaggwa Road Email : [email protected] P.O. Box 8147 Website : www.finance.go.ug Kampala- Uganda In any correspondence on this subject please quote No. HRM 155/222/02 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA 18th December, 2020 Telephone : 256 41 4707 000 : 256 41 4232 095 Ministry Of Finance, Planning Fax : 256 41 4230 163 : 256 41 4343 023 & Economic Development : 256 41 4341 286 Plot 2-12, Apollo Kaggwa Road Email : [email protected] P.O. Box 8147 Website : www.finance.go.ug Kampala- Uganda In any correspondence on this subject please quote No. HRM 155/222/02 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA 21st January, 2021 All Accounting Officers (Central and Local Government) Telephone : 256 41 4707 000 : 256 41 4232 095 Ministry Of Finance, Planning Fax : 256 41 4230 163 : 256 41 4343 023 & Economic Development : 256 41 4341 286 Plot 2-12, Apollo Kaggwa Road Email : [email protected] P.O. Box 8147 Website : www.finance.go.ug Kampala- Uganda In any correspondence on this subject please quote No. HRM 155/222/02 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA 19th February, 2021 All Accounting Officers (Central and Local Government) Telephone : 256 41 4707 000 : 256 41 4232 095 Ministry Of Finance, Planning Fax : 256 41 4230 163 : 256 41 4343 023 & Economic Development : 256 41 4341 286 Plot 2-12, Apollo Kaggwa Road Email : [email protected] P.O.