Mount Vernon Trail Corridor Study George Washington Memorial Parkway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Park Sites of the George Washington Memorial Parkway

National Park Service Park News and Events U.S. Department of the Interior Virginia, Maryland and Potomac Gorge Bulletin Washington, D.C. Fall and Winter 2017 - 2018 The official newspaper of the George Washington Memorial Parkway Edition George Washington Memorial Parkway Visitor Guide Drive. Play. Learn. www.nps.gov/gwmp What’s Inside: National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior For Your Information ..................................................................3 George Washington Important Phone Numbers .........................................................3 Memorial Parkway Become a Volunteer .....................................................................3 Park Offices Sites of George Washington Memorial Parkway ..................... 4–7 Alex Romero, Superintendent Partners and Concessionaires ............................................... 8–10 Blanca Alvarez Stransky, Deputy Superintendent Articles .................................................................................11–12 Aaron LaRocca, Events ........................................................................................13 Chief of Staff Ruben Rodriguez, Park Map .............................................................................. 14-15 Safety Officer Specialist Activities at Your Fingertips ...................................................... 16 Mark Maloy, Visual Information Specialist Dawn Phillips, Administrative Officer Message from the Office of the Superintendent Jason Newman, Chief of Lands, Planning and Dear Park Visitors, -

Site Report: Alexandria Federal Courthouse, Phase I

Alexandria' Federal Courthouse Phase I Historical and Archaeological Investigation' Alexandria, Virgi,nia ;~?~: :fr<,»1:' ~/ v" \~ :"::;~, <"' ,'" Submitted to Sverdrup Corporation ' Arlington, Virginia for General- Services Administration Washington, D.C. i',';' , ":" .•. ,, . June 19S1 'FW020 Engineering-Science, Inc. 1133 Fifteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20005 ALEXANDRIA FEDERAL COURTHOUSE PHASE I HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA Madeleine Pappas Janice G.Artemel Elizabeth A. Crowell June 1991 " • Submitted to Sverdrup Corporation Arlington, Virginia for General Services Administration Washington, D.C. Engineering-Science, Inc. 1133 Fifteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20005 • ) . J Alex{llIdria Federal Courthouse Phase I Ardzaeological Investigation • TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 1 List of Figures II List of Plates . III Acknowledgements IV I. Introduction A ProjeCt Location and Description 1 B. Methodology and Research Orientation 1 II. Existing Conditions 4 A .Climate 4 B. Geology and Soils 4 C. Stratigraphy 5 ill. Previous Investigations 11 IV. Previous Land Use 14 A. Prehistoric Summary 14 B. Historic Background 18 C. Project Area Property Title History 37 /V. Evaluation of Resources 41 • A Summary of Previous Site Use 41 B. Analysis of Subsurface Testing 42 C. Prehistoric Archaeological Potential 44 D. Historic Archaeological Potential 45 E. Summary of Archaeological Potential at BlockI 48 VI. Recommendations 51 Bibliography 54 , Appendices 63 A. List of Personnel 63 B. Resumes of Key Personnel 64 • Alexandria Federal Cowthouse Phase I Archaeological Investigation 11 LIST OF FIGURES • 1 . Project Location 2 2. Soil Borings 6 3. VVestAJexandria, 1804 20 4. AJexandria, 1845 23 5. U.S. Army Encampments South and VVest of AJexandria, 1861 25 6. -

Join Us for an Historic Event

Join Us for an Historic Event Symposium and Field Trip Commemorating The 70th Anniversary of The Founding of Camp Ritchie Military Intelligence Training Center And the Legacy of the “Ritchie Boys” June 18-19, 2012 Symposium Monday, June 18, 2012 • 9:00 am – 3:00 pm U.S. Navy Memorial 701 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. 20004-2608 Highlights include - keynote speech on the “Ritchie Boys” and their contributions to military intelligence - two panels of Ritchie Boys - one discussing the training at Camp Ritchie and the other recounting their experiences in WWII - presentation by the National Park Service on interpretation of WWII military history at national parks Field trip Tuesday, June 19, 2012 9:30 am – 3:00 pm - A chartered bus will depart Washington D.C. for Cascade, Maryland, and the home of Camp Ritchie, later known as Fort Ritchie. Tour will include lunch and luncheon speaker. Sponsors National Parks Conservation Association, National Park Service The International Spy Museum, The OSS Society, Holocaust Memorial Center, Michigan More than 19,000 “Ritchie Boys” had military intelligence training at Camp Ritchie between July 1942 and September 1945. About 80% of the “Ritchie Boys” served overseas. Some served at P.O. Box 1142, a top-secret military intelligence installation near Mount Vernon in Virginia (now Fort Hunt Park, part of the George Washington Memorial Parkway managed by the National Park Service). Lodging You must make your own lodging arrangements. Reserve your hotel room by: 1. No later than May 18, 2012, contacting Crystal City Marriott, near Washington Reagan National Airport, 1.800.228.9290 or 703.413.5500, and requesting the Ritchie Boys room block. -

Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport Terminal B/C

Executive Director’s Recommendation Commission Meeting: July 13, 2017 PROJECT NCPC FILE NUMBER Terminal B/C Redevelopment, Secure 7675 National Hall, and New North Concourse - Ronald Reagan Washington National NCPC MAP FILE NUMBER Airport 2105.00(38.00)44568 Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport APPLICANT’S REQUEST Arlington, Virginia Approval of preliminary and final SUBMITTED BY building plans Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority PROPOSED ACTION Approve of preliminary and final REVIEW AUTHORITY building plans Pursuant to a Memorandum of Understanding between the Metropolitan Washington Airports ACTION ITEM TYPE Authority and the National Capital Planning Staff Presentation Commission dated November 2, 1988, and D.C. Code § 9-1008(d)(2)(A). PROJECT SUMMARY The Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) submitted preliminary and final building plans for the Terminal B/C redevelopment project, which includes securing the National Hall with new checkpoints, a new North Concourse project, and the demolition of two existing hangars and central office building at Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (Reagan National Airport). To secure the National Hall, the project will relocate the existing security checkpoints from inside Terminal B/C to two separate areas outside this terminal adjacent to the pedestrian bridges connecting to the National Airport Metrorail Station. These two new structures will be located above the exiting arrivals roadway and below the exiting elevated departures roadway. MWAA is proposing to use glass and metal panel materials for the new checkpoint buildings, noting this design aesthetic will be compatible with the existing Terminal B/C in terms of scale, use of materials and architectural features. The standing seam non-reflective metal roof for the new checkpoint buildings has a curvilinear form and has its lowest height on the elevation adjacent to the elevated roadway so the height will not compete with the monumental quality of the exiting Terminal B/C domes. -

The Accelerating Erosion of Dyke Marsh Basic Findings of the U.S

The Accelerating Erosion of Dyke Marsh Basic Findings of the U.S. Geological Survey Study In 1940, the wetland known as Dyke Marsh was around 180 acres. By 2010, it was around 53 acres. Ned Stone It is eroding six to eight feet or 1.5 to two acres per Dyke Marsh shoreline erosion year on average. “Analysis of field evidence, aerial photography, and published maps has revealed an accelerating rate of erosion and marsh loss at Dyke Marsh, which now appears to put at risk the short term survivability of this marsh.” – USGS At this rate, Dyke Marsh could be gone in 30-40 years. Dredging of sand and gravel from 1940 to 1972 was a strong destabilizing force, transforming it from a net depositional state to a net erosional state. Dredging removed around 101 acres or 54 percent of the 1937 marsh. Erosion is both continuous and episodic. The chang- es caused by dredging have made the marsh subject to significant erosion by storm waves, especially from winds traveling upriver. Damaging storms oc- cur approximately every three years. Dredging out a promontory removed the geologic wave protection of the south marsh that existed back to at least 1864 and altered the size and func- tion of the tidal creek network. “This freshwater tidal marsh has shifted from a semi-stable net depositional environment (1864– 1937) into a strongly erosional one . The marsh has been deconstructed over the past 70 years by a combination of manmade and natural causes. The 1937 1959 2006 marsh initially experienced a strong destabilizing period between 1940 and 1972 by direct dredge The USGS study can be found at: www.pubs.usgs.gov/of/2010/1269. -

Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves Mary Geraghty College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Geraghty, Mary, "Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625788. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-jk5k-gf34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOMESTIC MANAGEMENT OF WOODLAWN PLANTATION: ELEANOR PARKE CUSTIS LEWIS AND HER SLAVES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mary Geraghty 1993 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts -Ln 'ln ixi ;y&Ya.4iistnh A uthor Approved, December 1993 irk. a Bar hiara Carson Vanessa Patrick Colonial Williamsburg /? Jafhes Whittenburg / Department of -

Learning About the New Deal and the Depression with a Trip to The

Learning About the New Deal and the Depression with a Trip to the Civilian Conservation Corps Museum Mary Sandkam, Richmond Originally published in the November-December 2017 issue of VaHomeschoolers Voice Virginia is such a wonderful state to live in for teaching history; we can immerse ourselves in almost any time period by taking a field trip within only a day’s drive. Colonial times? Hop into the car and head to Jamestown or Williamsburg. Revolutionary War? Head to Yorktown. The Civil War? Head to Richmond, Petersburg, or just about anywhere in the state. Civil Rights? Head to museums in Richmond and Washington, D.C. These are all straightforward field trips, though. What happens when you get to more esoteric topics? Most home- schoolers will agree that everything is learned more easily when experienced firsthand, so a harder-to-study topic, like the New Deal and the Depression, definitely deserves a field trip. In this case, you head to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Museum and then, if you have time, you head to CCC projects around the state. The CCC Museum is located in Pocahontas State Park, in Chesterfield County, 20 miles from downtown Richmond, and is one of just a few such museums in the nation. The hours vary seasonally, but you can call the park (804-796-4255) for information and to arrange group tours. It is a small museum but is chock full of information, and the park ranger on staff when we visited was incredibly helpful in answering all of our questions. The CCC was created by Franklin D. -

Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Working for You!

American Council of Engineering Companies of Metropolitan Washington Water & Wastewater Business Opportunities Networking Luncheon Presented by Matthew Doyle, Branch Chief, Wastewater Design and Construction Division Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Working for You! A Fairfax County, VA, publication August 20, 2019 Introduction • Matt Doyle, PE, CCM • Working as a Civil Engineer at Fairfax County, DPWES • BSCE West Virginia University • MSCE Johns Hopkins University • 25 years in the industry (Mid‐Atlantic Only) • Adjunct Hydraulics Professor at GMU • Director GMU‐EFID (Student Organization) Presentation Objectives • Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Infrastructure • Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Organization (Staff) • Snapshot of our Current Projects • New Opportunities To work with DPWES • Use of Technologies and Trends • Helpful Hyperlinks Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Infrastructure • Wastewater Collection System • 3,400 Miles of Sanitary Sewer (Average Age 60 years old) • 61 Pumping Stations (flow ranges are from 25 GPM to 25 MGD) • 90 Flow Meters (Mostly billing meters) • 135 Grinder pumps • Wastewater Treatment Plant • 1 Wastewater Treatment Plant • Noman M. Cole Pollution Control Plant, Lorton • 67 MGD • Laboratory • Reclaimed Water Reuse System • 6.6 MGD • 2 Pump Stations • 0.750 MG Storage Tank • Level 1 Compliance • Convanta, Golf Course and Ball Fields Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Organization • Wastewater Management Program (Three Areas) – Planning & Monitoring: • Financial, -

The Virginia Gazette : Genealogy

5o4s~. ,_Friday, January 14,, 1955 THE VIRGINIA GAZETTE, WILLIAMSBU Sarah ................ (b. ........, d. aft. 1684) & had, (7) John Billups ‘GENEALOGY (1660-aft. 1709) m.- bef. June 6, 1695 to Mary Gasscock & had (6) By Hugh 3. Watson Joseph Billups (1697-1767), m. 17l9, Margaret Lilly (1700-1770). WATSONIAN OBSERVATION orded in Petersburg, Va. Joanna & had (5) Robert Bil-.lups (Mar. OF THE WEEK: In our research Ellis is one of the witnesses with 1720- d. bef. 1795) m.- June 14, 1755 to Ann Ransone (b. ........, d. we find many unusual names and Wm Davis & Cyrus Ferguson to often wonder where they derived: ........), & had (4) John Billups (b. this will, naming the wife as Polly among some I have come across lvlar. 17, 1755-6, cl. Oct. 23. 1814) recently was the surname of & “my mother Letty Skipwith.” m.- 1798 to Susannah (Carleton) BIBLE; another was that of a This would show that the wife of Cox (b. 5-6-1761, d. 1-10-1817), gentleman by the name of “Wil Augustine Ellis may have been & had (3) Col. Thomas Carleton liam Crank Ford.” Perhaps some the Mary Skipwith. In the lineage Billups (b. 4-2-1804, d. 1866) m. 9-13-1847 to Frances Ann Saun of my readers have found some book of “National Society of just as unusual. Daughters of Founders & Pa ders (13.4-12-1808, (1. 6-1-1890), & triots,” Vo1.'XV, pp. 79-80 is had (2) James Saunders Billups QUERIES found the lineage of Mrs. John M. (b. 11-22-1808, d. 1-11-1919), m.-. -

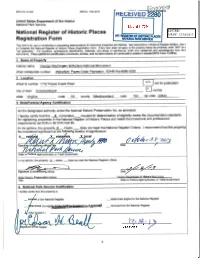

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NOV 0 ·~ 2013 National Register of Historic Places NAT. Re018TiR OF HISTORIC PlACES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name George Washington Birthplace National Monument other names/site number Wakefield. Popes Creek Plantation , VDHR File #096-0026 2. Location 1732 Popes Creek Road not for publication street & number L-----' city or town Colonial Beach ~ vicinity state Vir inia code VA county Westmoreland code _ _;_:19'--=-3- zip code -"'2=2:....;.4"""43.;;...._ ___ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _!__nomination_ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property .K._ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: x_ b state ' Ide "x n J.VIA.rVI In my opinion, the property .x..._ meets_ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Board Agenda Item July 30, 2019 ACTION

Board Agenda Item July 30, 2019 ACTION - 8 Endorsement of Design Plans for the Richmond Highway Corridor Improvements Project from Jeff Todd Way to Sherwood Hall Lane (Lee and Mount Vernon Districts) ISSUE: Board endorsement of the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) Design Public Hearing plans for the 3.1-mile Richmond Highway Corridor Improvements Project between Jeff Todd Way/Mount Vernon Memorial Highway and Sherwood Hall Lane. The purpose of the project is to increase capacity, safety, and mobility for all users. Improvements include widening Richmond Highway from four to six lanes; reserving the median for the future Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system; replacing structures over Dogue Creek, Little Hunting Creek, and the North Fork of Dogue Creek; intersection improvements; sidewalks; and two-way cycle tracks on both sides of the road. RECOMMENDATION: The County Executive recommends that the Board endorse the design plans for the Richmond Highway Corridor Improvements project administered by VDOT as generally presented at the March 26, 2019, Design Public Hearing and authorize the Director of FCDOT to transmit the Board’s endorsement to VDOT (Attachment I). TIMING: The Board should take action on this matter on July 30, 2019, to allow VDOT to proceed with final design plans and enter the Right-of-Way (ROW) phase in late 2019 to keep the project on schedule. BACKGROUND: In 1994, the Virginia General Assembly directed VDOT to perform a centerline design study of the 27-mile Route 1 corridor between the Stafford County line and the Capital Beltway. There was a continuation of the Centerline Study in 1996 and 1998. -

2015 Corridor Analysis of the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail in Northern Virginia

2015 Corridor Analysis Of the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail in Northern Virginia 0 http://www.novaregion.org/index.aspx?nid=299 Acknowledgements The Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) thanks the following individuals for their contributions to this report: • Donald Briggs, Superintendent of the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail for the National Park Service; • Ursula Lemanski, Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program for the National Park Service; • Mark Novak, Loudoun County Park Authority; • Debbie Andrews of Prince William County Department of Parks and Recreation; and • Members of the Potomac Heritage Trail Association. The report is an NVRC staff product, supported with funds provided by a cooperative agreement with the National Capital Region National Park Service (Grant Cooperative Agreement P14AC01704). Any assessments, conclusions, or recommendations contained in this report represent the results of the NVRC staff’s technical investigation and do not represent policy positions of the Northern Virginia Regional Commission unless so stated in an adopted resolution of said Commission. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the jurisdictions, the National Park Service, or any of its sub agencies. Report prepared by: Corey Miles, Senior Environmental Planner Northern Virginia Regional Commission Debbie Spiliotopoulos, Senior Environmental Planner Northern Virginia Regional Commission Figure 1 Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail Corridor 1 http://www.novaregion.org/index.aspx?nid=299 The Northern Virginia Regional Commission 2015 Commissioners Listed by Jurisdiction (As of December 2015) Commissioners are appointed by and from the governing bodies of NVRC’s member localities on a population-based representation formula.