6.1.05-Diana Kamel-Aleya-Abdel-Hadi-Pp 77

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamed Abdalla in Arabe 1977, Women = Man 1970, Quo Vadis ? 46 X 37 Cm, Mixed Med on Wood 29,5 X 21 Cm, Stencil, Acrylique, Spray 48 X 36 Cm, Ink, Silk Paper

HHHAAAMMMEEEDDD AAABBBDDDAAALLLLLLAAA Cover 1962 Next page Hamed Abdalla in arabe 1977, Women = Man 1970, Quo Vadis ? 46 x 37 cm, mixed med on wood 29,5 x 21 cm, stencil, acrylique, spray 48 x 36 cm, ink, silk paper HAMED ABDALLA Story of a life HAMED ABDALLA (1917 – 1985) by Roula El Zein . His works of art tell of revolt and resistance, of injustice and hope, of fellahins and modest people. They speak of revolution, of equality between man 1951 – Le grand-père, 32 x 22cm, lithographie and woman, of death and spirituality… He drew his subjects from Egypt, his native land, from its Pharaonic, Coptic and Islamic past and from its everyday life in the streets and the coffee-houses… For more than fifty years, Hamed Abdalla worked relentlessly, leaving behind him a big amount of paintings, drawings and lithographs that witness today of an ongoing research and a creation that knew no boundaries. Moreover, Hamed Abdalla left many writings for beyond drawing and painting, the man cultivated his art theory and had a passion for philosophy. Several exhibition catalogs, dozens of interviews done in various languages, hundreds of newspaper articles, studies made by others on his work, and a large number of letters were recorded and kept by his family; a precious documentation that reveals the life and work of a great artist who was also a great humanist. 1954 – Autoportrait de l’artiste, 39.5 x 29.5 cm, Gouache 1983, Al Joua’ - Hunger, 65 x 50 cm, acrylique appreciated for his beautiful calligraphy. Since adolescence, he begins to draw. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan ARABIC CALLIGRAPHY in CONTEMPORARY EGYPTIAN

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-6296 SIDA, Youssef Mohamed Ali, 1922- ARABIC CALLIGRAPHY IN CONTEMPORARY EGYPTIAN MURALS, WITH AN ESSAY ON ARAB TRADITION AND ART. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1965 Fine Arts University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan ARABIC CALLIGRAPHY IN CONTEMPORARY EGYPTIAN MURALS .WITH AN ESSAY ON ARAB TRADITION AND ART DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Youssef Mohamed Ali Sida, M. Ed. 4c * * * * * The Ohio State University 1965 / Approved by ) Adviser School of Fine and Applied Arts ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge my deepest gratitude to the professors and friends who encouraged and inspired me, who gave their pri vate time willingly, who supported me with their thoughts whenever they felt my need, and especially to all the members of my Graduate Committee, Professor Hoyt Sherman, Professor Franklin Ludden, Professor Francis Utley, Professor Robert King, and Professor Paul Bogatay. ii CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................. ii ILLUSTRATIONS................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION................................................................................... 1 Chapter I. CONTEMPORARY ART OF THE UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC.............................. 4 The Pioneers of Contemporary Egyptian Art Artists of the School of Fine Arts Artists of the School of Decorative Arts (The School of Applied Arts) The "free artists" The Pioneers of Art Education The Pioneers of Art Criticism The Art Movements Types of Contemporary Art Criticism in the United Arab Republic Summary H. ARA B NA TIONALISM AND ARA B CULTURE................ 21 Definition of nationalism Arab Faith and Culture The Influence of Cultures The Islam Influence on the Arts Summary Chapter Page m. -

Art Collector: 53 Works, a Century of Middle Eastern Art Part II, with Subtitles 7/4/17, 1:37 PM

Art Collector: 53 Works, A Century of Middle Eastern Art Part II, with subtitles 7/4/17, 1:37 PM 4 اﻟﻣزﯾد اﻟﻣدوﻧﺔ اﻹﻟﻛﺗروﻧﯾﺔ اﻟﺗﺎﻟﯾﺔ» إﻧﺷﺎء ﻣدوﻧﺔ إﻟﻛﺗروﻧﯾﺔ ﺗﺳﺟﯾل اﻟدﺧول Art Collector http://www.zaidan.ca Posts Comments Wednesday, November 25, 2015 Total Pageviews 53 Works, A Century of Middle Eastern Art Part II, with subtitles 163,283 A Century of Iraqi Art Part I & Modern & Contemporary Middle Eastern Art Search This Blog Nja mahdaoui jafr - The alchemy of signs Follow by Email Email address... VIEW OF THE TIGRIS Abdul Qadir Al Rassam, (1882 - 1952) 13.78 X 20.87 in (35 X 53 cm) oil on canvas Creation Date: 1934 Signed Abdul Qadir Al Rassam, (1882 - 1952), was born in Baghdad, Iraq. He was the first well-known painter in modern Iraq and the leader of realism school in Iraq. He studied military science and art at the Military College, Istanbul, Turkey, (then the capital of the Ottoman Empire) from 1904. He studied art and painting in the European traditional style and became a landscape painter, he painted many landscapes of Iraq in the realism style, using shading and composition to suggest time periods. He was a major figure among the first generation of modern Iraqi artists and was a member of the Art Friends Society (AFS, Jami’yat Asdiqa’ al- Fen). A collection of his work is hung in The Pioneers Museum, Baghdad. A prolific painter of oils, the majority of his works are now in private hands. More Nja mahdaoui jafr - The alchemy of signs Popular Posts 38 Artists Embedded of Arc's Military Campaign, (c. -

Egypt's Awakening and Modern & Contemporary Middle Eastern

EGYPT’S AWAKENING AND MODERN & CONTEMPORARY MIDDLE EASTERN ART Wednesday 18 April 2018 EGYPT’S AWAKENING AND MODERN & CONTEMPORARY MIDDLE EASTERN ART Wednesday 18 April 2018 at 3pm 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Sunday 15 April +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Nima Sagharchi Monday to Friday 8.30am - 6pm 11am to 3pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 8342 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Monday 16 April To bid via the internet please [email protected] 9am to 4.30pm visit bonhams.com As a courtesy to intending Tuesday 17 April Noor Soussi bidders, Bonhams will provide a 9am to 4.30pm Please note that bids should be +44 (0) 20 7468 8345 written Indication of the physical Wednesday 18 April submitted no later than 4pm [email protected] condition of lots in this sale if 9am to 12pm on the day prior to the sale. a request is received up to 24 New bidders must also provide CONDITION REPORTS hours before the auction starts. SALE NUMBER proof of identity when Requests for condition reports This written Indication is issued 24939 submitting bids. Failure to do for this sale should be emailed to: subject to Clause 3 of the Notice this may result in your bid not [email protected] to Bidders. CATALOGUE being processed. £30.00 ILLUSTRATIONS Telephone bidding can only Front cover: Lot 8 be accepted on lots with a Back cover: Lot 21 low-estimate in excess of Inside front cover: Lot 22 £1000. Inside back cover: Lot 10 Live online bidding is IMPORTANT INFORMATION available for this sale The United States Please email bids@bonhams. -

MODERN and CONTEMPORARY MIDDLE EASTERN ART Tuesday 28 November 2017

MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY MIDDLE EASTERN ART Tuesday 28 November 2017 Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. 4326560 Robert Brooks Co-Chairman, Colin Sheaf Chairman, Gordon McFarlan, Andrew McKenzie, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Harvey Cammell Deputy Chairman, Simon Mitchell, Jeff Muse, Mike Neill, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Antony Bennett, Matthew Bradbury, Charlie O’Brien, Giles Peppiatt, India Phillips, Matthew Girling CEO, Lucinda Bredin, Simon Cottle, Andrew Currie, Peter Rees, John Sandon, Tim Schofield, +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Patrick Meade Group Vice Chairman, Jean Ghika, Charles Graham-Campbell, Veronique Scorer, Robert Smith, James Stratton, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Jon Baddeley, Rupert Banner, Geoffrey Davies, Matthew Haley, Richard Harvey, Robin Hereford, Ralph Taylor, Charlie Thomas, David Williams, Jonathan Fairhurst, Asaph Hyman, James Knight, David Johnson, Charles Lanning, Grant Macdougall Michael Wynell-Mayow, Suzannah Yip. Caroline Oliphant, Shahin Virani, Edward Wilkinson, Leslie Wright. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY MIDDLE EASTERN ART Tuesday 28 November 2017 at 3pm 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Friday 24 November +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Nima Sagharchi Monday to Friday 8.30am - 6pm 12pm to 5pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 8342 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Sunday 26 November To bid via the internet please [email protected] 11am to 3pm visit bonhams.com As a courtesy to intending Monday 27 November Noor Soussi bidders, Bonhams will provide a 9am to 4.30pm Please note that bids should be +44 (0) 20 7468 8345 written Indication of the physical Tuesday 28 November submitted no later than 4pm [email protected] condition of lots in this sale if 9am to 12pm on the day prior to the sale. -

Exhibition Didactics

Taking Shape Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s This exhibition explores mid-twentieth-century abstract art from North Africa, West Asia, and the Arab diaspora—a vast geographic expanse that encompasses diverse cultural, ethnic, linguistic, and religious backgrounds. Comprising nearly ninety works by artists from countries including Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Qatar, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the exhibition is drawn from the collection of the Barjeel Art Foundation based in Sharjah, UAE. The paintings, sculpture, drawings, and prints on view here reflect the wide range of nonfigurative art practices that flourished in the Arab world over the course of four decades. Decolonization, the rise and fall of Arab nationalisms, socialism, rapid industrialization, wars and mass migrations, and the oil boom transformed the region during this period. With rising opposition to Western political and military involvement, many artists adopted critical viewpoints, striving to make art relevant to their own locales. New opportunities for international travel and the advent of circulating exhibitions sparked cultural and educational exchanges that exposed artists to multiple modernisms—including various modes of abstraction—and led them to consider their roles within an international context. The artists featured in this exhibition—a varied group of Arab, Amazigh (Berber), Armenian, Circassian, Jewish, Persian, and Turkish descent—sought to localize and recontextualize existing twentieth-century modernisms, some forming groups to address urgent issues. Moving away from figuration, they mined the expressive capacities of line, color, and texture. Inspired by Arabic calligraphy, geometry, and mathematics, Islamic decorative patterns, and spiritual practices, they expanded abstraction’s vocabulary—thereby complicating its genealogies of origin and altering the viewer’s understanding of nonobjective art. -

The Art of Lebanon Part Ii & Modern and Contemporary

MIDDLE EASTERN ART Wednesday 12 October 2016 12 Wednesday MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY THE ART OF LEBANON PART II & PART LEBANON ART OF THE THE ART OF LEBANON II AND MODERN MIDDLE EASTERN ART Ӏ New Bond Street, London Ӏ Wednesday 12 October 2016 THE ART OF LEBANON PART II Wednesday 12 October 2016, at 14.00 AND MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY MIDDLE EASTERN ART Wednesday 12 October 2016, at 14.30 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Sunday 9 October 2016 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Nima Sagharchi Monday to Friday 08:30 to 18:00 11:00 - 15:00 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 8342 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Monday 10 October 2016 To bid via the internet please [email protected] 9:00 - 16:30 visit bonhams.com As a courtesy to intending Tuesday 11 October 2016 Ralph Taylor bidders, Bonhams will provide a 9:00 - 16:30 Please note that bids should be +44 (0) 20 7447 7403 written Indication of the physical Wednesday 12 October 2016 submitted no later than 16:00 [email protected] condition of lots in this sale if 9:00 - 12:00 on the day prior to the sale. a request is received up to 24 New bidders must also provide Patrick Meade hours before the auction starts. SALE NUMBER proof of identity when submitting Group Vice Chairman This written Indication is issued bids. Failure to do this may result +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 subject to Clause 3 of the Notice 23907 in your bid not being processed. -

The High Dam at Aswan: History Building on the Precipice Author: Chaeri Lee

The High Dam at Aswan: History Building on the Precipice Author: Chaeri Lee DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2018.237 SourCe: Global Histories, Vol. 4, No. 2 (OCt. 2018), pp. 104-120 ISSN: 2366-780X Copyright © 2018 Chaeri Lee LiCense URL: https://CreativeCommons.org/liCenses/by/4.0/ Publisher information: ‘Global Histories: A Student Journal’ is an open-access bi-annual journal founded in 2015 by students of the M.A. program Global History at Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ‘Global Histories’ is published by an editorial board of Global History students in association with the Freie Universität Berlin. Freie Universität Berlin Global Histories: A Student Journal Friedrich-MeineCke-Institut Koserstraße 20 14195 Berlin Contact information: For more information, please consult our website www.globalhistories.Com or contact the editor at: [email protected]. THE FACE OF RAMSES II IS LIFTED INTO PLACE AT THE SitE OF REASSEMBLAGE OF THE GREAT TEMPLE OF ABU SIMBEL IN ASWAN, 1967. PHOTO COUrtESY OF: FORSKNING & FRAM- STEG. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS. The High Dam at Aswan: History Building on the Precipice CHAERI LEE Chaeri Lee is a student in the Global History Master’s program in Berlin, with a regional spe- cialisation in the Islamic World. For her undergraduate honor’s thesis at New York University Abu Dhabi, she wrote on the topic of the politics and aesthetics of Iranian coffeehouse paint- ings. She is interested in the visual culture of Iran and the Middle East at large, and in the in- vestigation of the layers of symbolism that are shared across, and claimed by, various political, intellectual, and artistic spectrums. -

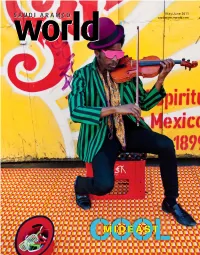

May/June 2011 Saudiaramcoworld.Com

May/June 2011 saudiaramcoworld.com COOLMIDEAST 2 Mideast saudiaramcoworld.com Cool Written by May/June 2011 Juliet Highet Published Bimonthly Vol. 62, No. 3 Using styles and media as diverse as the countries May/June 2011 saudiaramcoworld.com In a brash clash of colors, from which languages and pop fashion, they come, artists Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj’s upbeat portrait of musician of Middle Eastern Marques Toliver is among new origins, working in or art that is breaking from easy outside the Middle East, labels like “Arab” or “Middle are full of new energy that Eastern.” Courtesy of the artist COOLMIDEAST respects the past, is passionate about today and is helping to and Rose Issa Projects. create tomorrow. Publisher Assistant Editor SaudiPublisher Arabian Oil Company ArthurAdministration P. Clark (Saudi Aramco) Karim Khalil Aramco Services Company Administration Dhahran, Saudi Arabia Sarah Miller 9009 West Loop South Karim Khalil PresidentHouston, Texas and 77096, USA SarahCirculation Miller Chief Executive Officer Edna Catchings President and Circulation Khalid A. Al-Falih Chief Executive Officer EdnaDesign Catchings and Production ExecutiveAli A. Abuali Director Herring Design Design and Production Saudi Aramco Affairs Director HerringPrinted Design in the USA Khalid I. Abubshait Public Affairs RR Donnelley/Wetmore Printed in the USA GeneralMae S. Mozaini Manager RRAddress Donnelley/Wetmore editorial Public Affairs ISSN correspondence to: Nasser A. Al-Nafisee Address editorial 1530-5821 The Editor correspondence to: Manager Saudi Aramco World Editor The Editor Public Relations Post Office Box 2106 12 Robert Arndt Saudi Aramco World Tareq M. Al-Ghamdi Houston, Texas Managing Editor Post Office Box 2106 77252-2106 USA EditorDick Doughty Houston, Texas Robert Arndt 77252-2106 USA Assistant Editor ManagingArthur P. -

The Politics of Egyptian Fine Art

REPORT WORLD The Politics of Egyptian Fine Art Giving a Voice to the People MAY 16, 2017 — SULTAN SOOUD AL QASSEMI PAGE 1 Egyptian artists have a long history of political engagement. Even in the mid-twentieth century, when they mostly relied on state funding, they made critiques of the ruling regimes, and created one of the few spaces where independent political thought could brew. Egyptian artists—like their counterparts in many other countries in the region—have long been in closer touch with the mood of average people than the repressive governments have been, and they have served as both bellwethers and instigators of change. When the revolution broke out in 2011, Egyptian artists were thus well positioned to take on a much more direct, activist role, and many did. Art changed as well, becoming more accessible and purpose- driven. Now, as the tide again has turned to authoritarianism, the unbridled hope of the uprising has waned, negatively affecting art as much as any other part of the revolution. Yet there are glimmers of dissent in the art that lives on, and many reasons to think that Egyptian artists will be part of the vanguard of the next wave of social and political change, whatever it may be. Just after 3:00 a.m. on the morning of Friday, June 15, 2012, four young Egyptians, armed with spray cans and stencils, crept through the Cairo night. It was ten days before Egypt’s historic post-revolution election, the first free one in history. Their leader, underground artist El Zeft (a word that translates into “asphalt” but in colloquial Arabic is used to denote rubbish), took them to the former headquarters of the National Democratic Party (NDP), not too far from Tahrir Square, the site of the Egyptian uprising of 2011.