Tai Chi Chuan 1 Tai Chi Chuan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congratulations to Wudang San Feng Pai!

LIFE / HEALTH & FITNESS / FITNESS & EXERCISE Congratulations to Wudang San Feng Pai! February 11, 2013 8:35 PM MST View all 5 photos Master Zhou Xuan Yun (left) presented Dr. Ming Poon (right) Wudang San Feng Pai related material for a permanent display at the Library of Congress. Zhou Xuan Yun On Feb. 1, 2013, the Library of Congress of the United States hosted an event to receive Wudang San Feng Pai. This event included a speech by Taoist (Daoist) priest and Wudang San Feng Pai Master Zhou Xuan Yun and the presentation of important Wudang historical documents and artifacts for a permanent display at the Library. Wudang Wellness Re-established in recent decades, Wudang San Feng Pai is an organization in China, which researches, preserves, teaches and promotes Wudang Kung Fu, which was said originally created by the 13th century Taoist Monk Zhang San Feng. Some believe that Zhang San Feng created Tai Chi (Taiji) Chuan (boxing) by observing the fight between a crane and a snake. Zhang was a hermit and lived in the Wudang Mountains to develop his profound philosophy on Taoism (Daoism), internal martial arts and internal alchemy. The Wudang Mountains are the mecca of Taoism and its temples are protected as one of 730 registered World Heritage sites of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Wudang Kung Fu encompasses a wide range of bare-hand forms of Tai Chi, Xingyi and Bagua as well as weapon forms for health and self-defense purposes. Traditionally, it was taught to Taoist priests only. It was prohibited to practice during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966- 1976). -

Meihuaquan E Shaolinquan, Intrecci Leggendari

Questo articolo è un estratto del libro “ Il Meihuaquan: una ricerca da Chang Dsu Yao alle origini ” di Storti Enrico e altri Presentazione: Oggi questo testo rimane la testimonianza di un indagine che nuovi studi rendono un po’ datata. In particolare sempre più evidente è anche l’intreccio del Meihuaquan con la religione Buddista oltre che con quella Taoista e con il Confucianesimo. Resta invece mitologico il legame con il Tempio Shaolin ed il relativo pugilato. Rimangono comunque tanti altri interessanti spunti di riflessione. Meihuaquan e Shaolinquan, intrecci leggendari Classica foto sotto l’ingresso del tempio Shaolin Nei libri che parlano di Meihuaquan 梅花拳 emerge chiaramente il legame tra la Boxe del Fiore di Prugno ed il Taoismo ortodosso, sia perché se ne riconduce l’origine al Kunlun Pai 1, una scuola Taoista, sia perché membri importanti del Meihuaquan sono stati anche membri di sette quali Longmen 2 o Quanzhen , ma, cosa 1昆仑派 Scuola Kunlun 2 Han Jianzhong 韩建中, Meihuazhuang Quan ji Meihuazhuang Quan Daibiao Renwu 梅花桩拳及梅花桩拳代表人物 (La Scuola di Pugilato dei Pali del fiore di prugno e le figure rappresentative di questa scuola), articolo apparso nel numero 05 del 2007 della rivista Zhonghua Wushu 中华武术: 梅花桩拳传承的一百个字与道教传承的一百个字基本相同,梅花桩拳理中的天人合一、顺其自然等等,均说明 梅花桩拳与道教文化有着密切的联系,所以梅花桩拳中又流传有僧门道派和龙门道派等众多说法。 più importante, la teoria di questo stile si rifà alla filosofia Taoista. Quali sono allora i collegamenti con lo Shaolin Pai 少林派 (scuola Shaolin) visto che qualcuno fa risalire il Meihuaquan a questa scuola? E’ il Meihuaquan uno stile Shaolin? -

Yang Family, Yang Style楊家,楊式

Yang Family, Yang Style 楊家,楊式 by Sam Masich Frequently I am asked questions about the curriculum of Yang Style Taijiquan. What does it include? Why do some schools include material that others don’t? Why are some practices considered legitimate by some teachers but not by others? In order to understand the variances in curriculum from school to school it is first necessary to understand a few historical factors relating to the creation of this branch of Taijiquan as well as the opinions of the Yang family itself. In 1990 I had the fortune of riding with master Yang Zhenduo from Winchester, Virginia to Washington D.C. in a van filled with Tai Chi players. We were all going to the Smithsonian institute and to see the sights. It was a sunny day and everyone in the vehicle was in very good spirit after an intense, upbeat five-day workshop. The mood was relaxed and, as I was sitting close to Master Yang and his translator, I took the opportunity to ask some questions about his life in China, his impressions of America, his training and his views on Tai Chi. At some point I came to the subject of curriculum and asked him, among other things, what he thought about the 88 movement Yang Style Taijiquan San Shou (Sparring) routine. Master Yang said, "This is Yang Style Taijiquan not Yang Family Taijiquan." He went on further to explain that this was the creation of his fathers’ students and that, while it adhered well to the principles of his father’s teachings, it was not to be considered part of the Yang Family Taijiquan. -

2019 Saturday & Sunday Workshop Descriptions and Instructor Bio's

2019 Saturday & Sunday Workshop Descriptions and Instructor Bio’s Arms don't move; or do they? Frames of reference (Saturday, 5:10 to 6:20) Instruction: DAVID BRIGGS Description: Explore the body mechanics of movement within your form and practice. Improve your own practice with a better understanding of the development of Qi and power through connected movement. BIO: Dave Briggs started training Martial Arts in 1970. He started Tai Chi Chuan in 1980 under Susanna DeRosa and through her met and studied with Master JouTsung Hwa. He has dedicated his life to the motto "Seek not the masters of old .. seek what they sought." Tai Chi Warmups (Saturday, 10:20 to 11:30) Instruction: DAVID CHANDLER, Waterford, CT (www.eaglesquesttaichi.com) Description: This set of Tai Chi Warm ups, put together by David Chandler, include Qigong, Soon Ku, Indonesian Hand Dances, Circular Patterns, Swinging Motions and stretching practices culled from many different traditions of Tai Chi Chuan. These simple techniques can be done alone or prior to Form work for dynamic health benefits. Appropriate for all levels. An instructional DVD is available for purchase for home practice. Sun Style Basics (Saturday, 5:10 to 6:20) Instruction: DAVID CHANDLER, Waterford, CT (www.eaglesquesttaichi.com) Description: Sun Style Tai Chi, also known as Open Close Tai Chi, is a synthesis of Hsing-I, Bagua and Tai Chi, promoting maximum cultivation and flow of energy. Movements help the player to develop balance, flexibility and strength while amplifying internal energy awareness. This workshop will cover the basic fundamentals of Sun Style as well as the beginning movements of a Sun Form. -

Taiji Jest Tylko Jedno

Taiji jest tylko jedno 1 Spis treści Zamiast wstępu…………………………………………………………..……………………………………………………………………………….…………………………………………………3 Podziękowanie………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………………………………………………5 Drzewo genealogiczne stylu Yang Taiji rodziny Fu…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Część I. Autor: Marvin Smalheiser Ostatni Wywiad z Fu Zhongwen’em………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7 Część II. Autor: Ted W. Knecht Niezapomniane spotkanie z Fu Zhongwen’em………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………..15 Bibliografia………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………18 2 Zamiast wstępu Opracowanie „Taiji jest tylko jedno” zawiera dwa artykuły na temat działalności Wielkiego Mistrza stylu Yang Taijiquan – Fu Zhong Wen’a. Pochodzą one z pierwszej połowy lat 90-tych ubiegłego wieku i zostały opublikowane w czasopiśmie T’ai Chi Magazine, opisującym chińskie, wewnętrzne sztuki walki. Marvin Smalheiser1, założyciel, wydawca i redaktor naczelny tego działającego od 1977 roku periodyku przez niemal czterdzieści lat prowadził badania na temat stylu Yang taijiquan. Jego dociekliwość i przy tym duża otwartość na ludzi zapewniała licznym studentom oraz anglojęzycznym pasjonatom tej sztuki walki dostęp do wiarogodnych informacji źródłowych. Wiedzę tę gromadził latami. Na bazie wieloletnich doświadczeń wyniesionych z pracy szkoleniowej z mistrzami kungfu dawał innym praktykom taiji nieocenione wsparcie poradnicze z zakresu ćwiczeń mających na celu utrzymanie ciała w dobrej kondycji i sprawności -

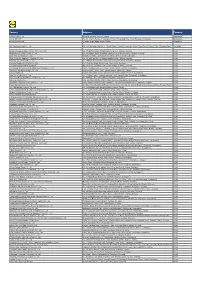

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

1001 Years of Missing Martial Arts

1001 Years of Missing Martial Arts IMPORTANT NOTICE: Author: Master Mohammed Khamouch Chief Editor: Prof. Mohamed El-Gomati All rights, including copyright, in the content of this document are owned or controlled for these purposes by FSTC Limited. In Deputy Editor: Prof. Mohammed Abattouy accessing these web pages, you agree that you may only download the content for your own personal non-commercial Associate Editor: Dr. Salim Ayduz use. You are not permitted to copy, broadcast, download, store (in any medium), transmit, show or play in public, adapt or Release Date: April 2007 change in any way the content of this document for any other purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of FSTC Publication ID: 683 Limited. Material may not be copied, reproduced, republished, Copyright: © FSTC Limited, 2007 downloaded, posted, broadcast or transmitted in any way except for your own personal non-commercial home use. Any other use requires the prior written permission of FSTC Limited. You agree not to adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any of the material contained in this document or use it for any other purpose other than for your personal non-commercial use. FSTC Limited has taken all reasonable care to ensure that pages published in this document and on the MuslimHeritage.com Web Site were accurate at the time of publication or last modification. Web sites are by nature experimental or constantly changing. Hence information published may be for test purposes only, may be out of date, or may be the personal opinion of the author. Readers should always verify information with the appropriate references before relying on it. -

Historia TAI CHI CHUAN - Opracowanie Na Podstawie Informacji Z Internetu I Książek (M.In

pokolenie historia TAI CHI CHUAN www.chentaichi.pl - opracowanie na podstawie informacji z internetu i książek (m.in. "Chen Żywe Taijiquan w klasycznym stylu" - Jan Silberstorff) - w razie zauważonych błędów proszę o kontakt: [email protected] 1 Chen Bu (1368 - 1644) 4* STYL CHEN … … … … 9 Chen Wang Ting (1597 - 1664) 1* powstanie tai chi 10 Jiang Fa Chen Ruxin 11 Chen Dakun Chen Dufeng 12 Chen Shantong Chen Shanzi 13 Chen Bingqi Chen Bingren Cheng Bing Wang POCZĄTEK STYLU YANG 14 Chen Chang Xing - stara forma - (1771 - 1853) 2* 15 Chen Gengyun Chen Ho Hai Yang Lu Chan (1799-1872) 7* 16 Chen Yannian Chen Yan Xi (mistrz starego stylu) Yang Banhou (1837-1892) Yang Jianhou (1839-1917) 17 Chen Lianke Chen Dengke Chen Fa Ke (1887 - 1957) 3* Quan You (1834-1902) nowy styl WU Yang Shaohu Yang Chengfu (1803-1935) 8* Xu Yusheng Założyciel dzisiejszego YANG 18 Chen Zhaochi Chen Zhaotanhg Chen Zhaoxu - 5* Chen ZhaoKui (1928-1981) 19* Wu Jianquan (1870-1902) nowy styl WU Chen Zhaopi 19* Chen Zhaopu Ma Yuliang (1901-1998) Fu Zhongwen Yang Zhenduo (ur. 1925) 9* Zheng Manquing Chen Weiming Chen Zhaohai obecny spadkobierca Yang 19 Chen Yinghe Chen Xiaowang (1945) 10* Chen Xiaoxing 14* Ma Jiangbao (ur. 1941) najstarszy syn brat Chen Xiaowang Chen Bing Chen Jun Chen Yingjun 16* najstarszy syn Chen Xiaoxinga (1971-) pierwszy syn mistrza drugi syn mistrza Chen Ziqiang 15* Chen Zhenglei 13* Wang Xi'an 12* Zhu Tiancai 11* 4 smoki rodziny chen, główni spadkobiercy stylu. Większość obecnie znanych mistrzów Chen Taiji zostało wytrenowanych przez dwóch mistrzów 18 pokolenia rodziny Chen. -

Tai Chi Chuan Martial Applications: Advanced Yang Style Tai Chi Chaun Pdf

FREE TAI CHI CHUAN MARTIAL APPLICATIONS: ADVANCED YANG STYLE TAI CHI CHAUN PDF Jwing-Ming Yang | 364 pages | 05 Nov 1996 | YMAA Publication Center | 9781886969445 | English | Rochdale, United States Tai Chi Chuan Martial Applications: Advanced Yang Style by Jwing-Ming Yang The Yang family first became involved in the study of t'ai chi ch'uan taijiquan in the early 19th century. Yang became a teacher in his own right, and his subsequent expression of t'ai chi ch'uan became known as the Yang-style, and directly led to the development of other three major styles of t'ai chi ch'uan see below. Yang Luchan and some would say the art of t'ai chi ch'uan, in general came to prominence as a result of his being hired by the Chinese Imperial family to teach t'ai chi ch'uan to the elite Palace Battalion of the Imperial Guards ina position he held until his death. Yang Jianhou the third son Yang Chien-hou Jianhou — passed on the middle frame long form, sometimes called the 2nd generation Yang form or the Yang Jian hou form to his disciples who still pass on this more martial form that is when seen more reminiscent of Chen style for which it is closer to in time as well as form than the Yang Cheng fu form or 3rd generation styles. Thus, Yang Chengfu is largely responsible for standardizing and popularizing the Yang-style t'ai chi ch'uan widely practised today. Yang Chengfu developed his own shortened "large frame" version of the Yang long Form, in order to make it easier to teach to modern students who are busy with modern life. -

Copyright by Shaohua Guo 2012

Copyright by Shaohua Guo 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Shaohua Guo Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE EYES OF THE INTERNET: EMERGING TRENDS IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE CULTURE Committee: Sung-Sheng Yvonne Chang, Supervisor Janet Staiger Madhavi Mallapragada Huaiyin Li Kirsten Cather THE EYES OF THE INTERNET: EMERGING TRENDS IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE CULTURE by Shaohua Guo, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2012 Dedication To my grandparents, Guo Yimin and Zhang Huijun with love Acknowledgements During the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in China in 2003, I, like many students in Beijing, was completely segregated from the outside world and confined on college campus for a couple of months. All activities on university campuses were called off. Students were assigned to designated dining halls, and were required to go to these places at scheduled times, to avoid all possible contagion of the disease. Surfing the Web, for the first time, became a legitimate “full-time job” for students. As was later acknowledged in the Chinese media, SARS cultivated a special emotional attachment to the Internet for a large number of the Chinese people, and I was one of them. Nine years later, my emotional ties to the Chinese Internet were fully developed into a dissertation, for which I am deeply indebted to my advisor Dr. Sung- Sheng Yvonne Chang. -

Sistema De Ranking Para O Estilo Yang De Tai Chi Chuan

Tai Chi - Ranking Seguindo as necessidades e o desenvolvimento das artes marciais, o Instituto de Artes Marciais Chinesas implementou em 1997, o sistema de graduações para as artes marciais chinesas, para avaliar o nível de habili- dade e contribuições dos praticantes e das pessoas que trabalham no campo das artes marciais formalmente. Nos últimos dois anos de desenvolvimento, alcançou sucesso entre os praticantes e artistas marciais profi s- sionais. A Associação Internacional, com o objetivo de adaptar à ordem atual das artes marciais chinesas e melhorar o desenvolvimento futuro do Tai Chi Chuan, criou o sistema de graduações para os praticantes do Tai Chi Chuan. A estrutura da Associação do Sistema de Graduações está baseada no “Sistema de Ranks das Artes Marciais Chinesas”. Sistema de Ranking para o Estilo Yang de Tai Chi Chuan Artigo I – Propósito Este sistema de ranking foi desenvolvido especifi camente para promover o desenvolvimento do Estilo Yang de Tai Chi Chuan, elevar o nível de habilidade e teoria dentro do Estilo Yang de Tai Chi Chuan e estabelecer um sistema de treino unifi cado dentro do mesmo. Artigo II – Nomes dos Graus Há nove graus que serão nomeados de acordo com uma variedade de fatores. O tempo de pratica, o nível de habilidade e teórico do praticante. Pesquisas realizadas, o respeito ao código ético das artes marciais e as contribuições para o desenvolvimento do Estilo Yang de Tai Chi Chuan, são considerados na avaliação dos graus. Estes são como segue: • Graduação de Iniciante: Um, dois e três. • Graduação Intermediária: Quatro, cinco e seis. • Graduação Avançada: Sete, oito e nove. -

Grandmaster Yang Jun on the Tai Chi Transformation

LIFE / HEALTH & FITNESS / FITNESS & EXERCISE Grandmaster Yang Jun on the Tai Chi transformation August 16, 2014 1:15 PM MST View all 18 photos Grandmaster Yang Jun (in white) demonstrated Two-person Tai Chi. Li Ping Five years ago at the first International Tai Chi (Taiji) Symposium, Grandmaster Yang Jun demonstrated his leadership by uniting all five major Tai Chi families together. At the time he was still under the tutelage of his grandfather Grandmaster Yang Zhenduo on Tai Chi chuan. Now at age 46, he is one of the youngest grandmasters in the world of Tai Chi chuan. Violet Li Born in 1968, Grandmaster Yang Un is the 6th generation descendant of the creator of Yang Style Tai Chi chuan and the future bearer of the Yang Family heritage. During the recent 2014 International Tai Chi Symposium held in Louisville, KY, Grandmaster Yang was the last keynote speaker. With confidence and pride, he agilely skipped up a few steps to the stage in his polo shirt and blue jeans. He delivered a solid speech in English without a translator. He spoke about his ancestor Grandmaster Yang Luchan studied Tai Chi from the 14th generation Chen family Grandmaster Chen Changxin. Having completed his training, Yang Luchan returned to Beijing and taught many the art of Tai Chi chuan and one of his students was Grandmaster Wu Yuxian, who later also went to study Chen Tai Chi directly from a Chen family member and created Wu/Hao Tai Chi style. The Wu style and the Sun Style were directly and indirectly influenced by the Chen Style as well as the Yang Style.