Remember the Beats?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8021/howl-the-naked-bodies-of-madness-118021.webp)

Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10352/ Published chapter Rodosthenous, George (2005) The dramatic imagery of "Howl": the [naked] bodies of madness. In: Howl for Now. Route Publishing , Pontefract, UK, pp. 53- 72. ISBN 1 901927 25 3 White Rose Research Online [email protected] The dramatic imagery of “Howl”: the [naked] bodies of madness George Rodosthenous …the suffering of America‘s naked mind for love into an eli eli lamma lamma sabacthani saxophone cry that shivered the cities (―Howl‖, 1956) Unlike Arthur Rimbaud who wrote his ―A Season in Hell‖ (1873) when he was only 19 years old, Allen Ginsberg was 29 when he completed his epic poem ―Howl‖ (1956). Both works encapsulate an intense world created by the imagery of words and have inspired and outraged their readers alike. What makes ―Howl‖ relevant to today, 50 years after its first reading, is its honest and personal perspective on life, and its nearly journalistic, but still poetic, approach to depicting a world of madness, deprivation, insanity and jazz. And in that respect, it would be sensible to point out the similarities of Rimbaud‘s concerns with those of Ginsberg‘s. They both managed to create art that changed the status quo of their times and confessed their nightmares in a way that inspired future generations. Yet there is a stark contrast here: for Rimbaud, ―A Season in Hell‖ was his swan song; fortunately, in the case of Ginsberg, he continued to write for decades longer, until his demise in 1997. -

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a Result of Moving to San Francisco in 1954, After His Psychiatric Hospitalizati

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a result of moving to San Francisco in 1954, after his psychiatric hospitalization, Allen Ginsberg made a complete transformation from his repressed, fragmented early life to his later life as an openly gay man and public figure in the hippie and environmentalist movements of the 1960s and 1970s. He embodied many contradictory beliefs about himself and his literary abilities. His early life in Paterson, New Jersey, was split between the realization that he was a literary genius (Hadda 237) and the desire to escape his chaotic life as the primary caretaker for his schizophrenic mother (Schumacher 8). This traumatic early life may have lead to the development of borderline personality disorder, which became apparent once he entered Columbia University. Although Ginsberg began writing poetry and protest letters to The New York Times beginning in high school, the turning point in his poetry, from conventional works, such as Dakar Doldrums (1947), to the experimental, such as Howl (1955-1956), came during his eight month long psychiatric hospitalization while a student at Columbia University. Although many critics ignore the importance of this hospitalization, I agree with Janet Hadda, a psychiatrist who examined Ginsberg’s public and private writings, in her assertion that hospitalization was a turning point that allowed Ginsberg to integrate his probable borderline personality disorder with his literary gifts to create a new form of poetry. Ginsberg’s Early Life As a child, Ginsberg expressed a strong desire for a conventional, boring life, where nothing exciting or remarkable ever happened. He frequently escaped the chaos of 2 his mother’s paranoid schizophrenia (Schumacher 11) through compulsive trips to the movies (Hadda 238-39) and through the creation of a puppet show called “A Quiet Evening with the Jones Family” (239). -

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

Neal Cassady and His Influence on the Beat Generation

PALACKÝ UNIVERSITY OLOMOUC FACULTY OF ARTS Department of English and American Studies Veronika Nováková Neal Cassady and His Influence on the Beat Generation Bachelor Thesis Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Matthew Sweney, Ph.D. Olomouc 2016 UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Veronika Nováková Neal Cassady a jeho vliv na beat generation Bakalářská práce Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Matthew Sweney, Ph.D. Olomouc 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma "Neal Cassady and His Influence on the Beat Generation" vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V ...................... dne...................... Podpis ............................ Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to PhDr. Matthew Sweney, Ph.D. for supervising my thesis and for his help. Table of contents Table of contents.......................................................................................................................6 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................7 2. The Real Neal Cassady ......................................................................................................9 2.1. Youth ........................................................................................................................9 2.2. Marriages ............................................................................................................... -

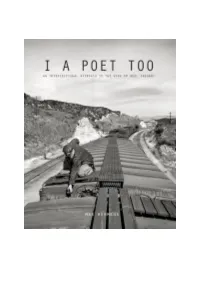

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

English Department Newsletter May 2016 Kamala Nehru College

WHITE NOISE English Department Newsletter May 2016 Cover Art by Vidhipssa Mohan Vidhipssa Art by Cover Kamala Nehru College, University of Delhi Contents Editorial Poetry and Short Prose A Little Girl’s Day 4 Aishwarya Gosain The Devil Wears Westwood 4 Debopriyaa Dutta My Dad 5 Suma Sankar Is There Time? 5 Shubhali Chopra Numb 6 Niharika Mathur Why Solve a Crime? 6 Apoorva Mishra Pitiless Time 7 Aisha Wahab Athazagoraphobia 7 Debopriyaa Dutta I Beg Your Pardon 8 Suma Sankar Toska 8 Debopriyaa Dutta Prisoner of Azkaban 8 Abeen Bilal Saudade 9 Debopriyaa Dutta Dusk 11 Sagarika Chakraborty Man and Time 11 Elizabeth Benny Pink Floyd’s Idea of Time 12 Aishwarya Vishwanathan 1 Comics Bookstruck 14 Abeen Bilal The Kahanicles of Maa-G and Bahu-G 15 Pratibha Nigam Rebel Without a Pause 16 Jahnavi Gupta Research Papers Heteronormativity in Homosexual Fanfiction 17 Sandhra Sur Identity and Self-Discovery: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road 20 Debopriyaa Dutta Improvisation and Agency in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night 26 Sandhra Sur Woman: Her Own Prisoner or the Social Jailbird and the Question of the Self 30 Shritama Mukherjee Deconstructing Duryodhana – The Villain 37 Takbeer Salati Translations Grief-Stricken (Translation of Pushkar Nath’s Urdu story “Dard Ka Maara”) 39 Maniza Khalid and Abeen Bilal Alone (Translation of Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali story “Ekla”) 42 Eesha Roy Chowdhury Beggar’s Reward (Translation of a Hindi Folktale) 51 Vidhipssa Mohan Translation of a Hindi Oral Folktale 52 Sukriti Pandey Artwork Untitled 53 Anu Priya Untitled 53 Anu Priya Saving Alice 54 Anu Priya 2 Editorial Wait, what is that? Can you hear it? Can you feel it? That nagging at the back of your mind as you lie in bed till ten in the morning when you have to submit an assignment the next day? That bittersweet feeling as you meet a friend after ages knowing that tomorrow you will have to retire to your mundane life. -

A History of Modern Drama

Krasner_bindex.indd 404 8/11/2011 5:01:22 PM A History of Modern Drama Volume I Krasner_ffirs.indd i 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM Books by David Krasner An Actor’s Craft: The Art and Technique of Acting (2011) Theatre in Theory: An Anthology (editor, 2008) American Drama, 1945–2000: An Introduction (2006) Staging Philosophy: New Approaches to Theater, Performance, and Philosophy (coeditor with David Saltz, 2006) A Companion to Twentieth-Century American Drama (editor, 2005) A Beautiful Pageant: African American Theatre, Drama, and Performance, 1910–1927 (2002), 2002 Finalist for the Theatre Library Association’s George Freedley Memorial Award African American Performance and Theater History: A Critical Reader (coeditor with Harry Elam, 2001), Recipient of the 2002 Errol Hill Award from the American Society for Theatre Research (ASTR) Method Acting Reconsidered: Theory, Practice, Future (editor, 2000) Resistance, Parody, and Double Consciousness in African American Theatre, 1895–1910 (1997), Recipient of the 1998 Errol Hill Award from ASTR See more descriptions at www.davidkrasner.com Krasner_ffirs.indd ii 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM A History of Modern Drama Volume I David Krasner A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication Krasner_ffirs.indd iii 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM This edition first published 2012 © 2012 David Krasner Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. -

The Portable Beat Reader Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE PORTABLE BEAT READER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ann Charters | 688 pages | 07 Oct 2014 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780142437537 | English | London, United Kingdom The Portable Beat Reader PDF Book What We Like Waterproof design is lightweight Glare-free screen. Nov 21, Dayla rated it it was amazing. See all 6 brand new listings. Night mode automatically tints the screen amber for midnight reading. The author did an excellent job of reviewing each writer - their history, works, etc - before each section. Diane DiPrima Dinners and Nightmares excerpt 5. Animal Farm and by George Orwell and A. Get BOOK. Quick Links Amazon. Although in retrospect, my knowledge was hardly rich with understanding, even though I'd read some Burroughs, knew of Kerouac and On the Road , Ginsberg and Howl. And last but not least, Family Library links your Amazon account to that of your relatives to let you conveniently share books. Again, no need to sit down and read the whole thing. She guides you through all the sections of the Beats Generation: Kerouac's group in New York, the San Francisco Poets, and the other groups that were inspired by the work these groups produced. Members Reviews Popularity Average rating Mentions 1, 7 10, 4. First off, Amazon has included a brand-new front light that allows you to read in the dark, something that was previously only available on the more expensive Kindle Paperwhite. But Part 5 was my joy! E-readers are also a great option for kids to explore. Status Charters, Ann Editor primary author all editions confirmed Baraka, Amiri Contributor secondary author all editions confirmed Bremser, Ray Contributor secondary author all editions confirmed Bukowski, Charles Contributor secondary author all editions confirmed Burroughs, William S. -

“But Cantos Oughta Sing”: Jack Kerouac's Mexico City

The Albatross is pleased to feature the graduating essay of Jack Derricourt which won the 2011 English Honours Essay Scholarship. “But Cantos Oughta Sing”: Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues and the British-American Poetic Tradition Jack Derricourt During the post-war era of the 1950s, American poets searched for a new direction. The Cold War was rapidly reshaping the culture of the United States, including its literature, stimulating a variety of poets to rein- terpret the historical lineage of poetic expression in the English language. Allen Grossman, a poet and critic who undertook such a reshaping in the fifties, turns to the figure of Caedmon from the Venerable Bede’s early eighth century Ecclesiastical History of the English People to seek out the roots of British-American poets. For Grossman, Caedmon represents an important starting point within the long tradition of English-language poetry: Bede’s visionary layman crafts a non-human narrative—a form of truth witnessed beyond the confines of social institutions, or transcend- ent truth—and makes it intelligible through the formation of conventional symbols (Grossman 7). The product of this poetic endeavour is the song. The figure of Caedmon also appears in the writings of Robert Duncan as a model of poetic transference: I cannot make it happen or want it to happen; it wells up in me as if I were a point of break-thru for an “I” that may be any person in the cast of a play, that may like the angel speaking to Caedmon to command “Sing me some thing.” When that “I” is lost, when the voice of the poem is lost, the matter of the poem, the intense infor- mation of the content, no longer comes to me, then I know I have to wait until that voice returns. -

The Importance of Neal Cassady in the Work of Jack Kerouac

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2016 The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac Sydney Anders Ingram As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Sydney Anders, "The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac" (2016). MSU Graduate Theses. 2368. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/2368 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Sydney Ingram May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Sydney Anders Ingram ii THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC English Missouri State University, May 2016 Master of Arts Sydney Ingram ABSTRACT Neal Cassady has not been given enough credit for his role in the Beat Generation. -

A Marxist Analysis of Beat Writing and Culture from the Fifties to the Seventies

The Working Class Beats: a Marxist analysis of Beat Writing and Culture from the Fifties to the Seventies. Paul Whiston Sheffield University, United Kingdom Introduction: a materialist concept of ‘Beat’ The Beat Generation was more than just a literary movement; it was, as John Clellon Holmes, stated ‘an attitude towards life’.1 In other words, the Beat movement was a social, cultural and literary phenomenon. I will analyse what this Beat ‘attitude’ actually meant and also what the relationship between the literature and the Beat culture was. In A Glossary of Literary Terms Abrams defines ‘Beat’ as signifying ‘both “beaten down” (that is, by the oppressive culture of the time) and “beatific” (many of the Beat writers cultivated ecstatic states by way of Buddhism, Jewish and Christian mysticism, and/or drugs that induced visionary experiences)’.2 My focus will be on the beaten down aspects of Beat writing. I will argue that this represents a materialist concept of ‘Beat’ (as opposed to the ‘spiritual’ beatific notion) which aligns with Marx’s ideas in The German Ideology.3 Given that ‘beaten down’ is defined in terms of cultural oppression I will put forward the thesis that the culturally oppressed writers of the Beat Generation were those of a working-class background (particularly Cassidy and Bukowski) and it was their ability to create a class-consciousness that gave Beat writing and culture its politically radical edge. 1 I question the extent to which the likes of Ginsberg and Kerouac were really ‘beaten down’. Evidence will be shown to prove that most of these ‘original’ Beats had a privileged upbringing and a bourgeois/bohemian class status, therefore being ‘Beat’, for them, was arguably a ‘hip’ thing to be, an avant-garde experiment. -

Male View of Women in the Beat Generation

Fredrik Olsson (6 March 1979) A60 Term Paper Autumn 2005 Department of English Lund University Supervisor: Annika Hill Male view of women in the Beat Generation – A study of gender in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. THE BEAT GENERATION ............................................................................................................................ 3 2. MALE BONDING AND MARGINALIZED WOMEN................................................................................. 4 3. WOMEN AND SOCIETY – GENDER PROBLEMS.................................................................................... 6 4. OBJECTIFICATION OF WOMEN ............................................................................................................... 9 THE MALE GAZE ................................................................................................................................................ 10 GETTING THE KICKS .......................................................................................................................................... 12 THE FEMALE BACKLASH .................................................................................................................................... 14 5. FROM BEATS TO FAMILY......................................................................................................................... 15 CONCLUSION...................................................................................................................................................