The Study Guide Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAF Edmonton E-Notes 2015 January

Page 1 of 4 LEAF EDMONTON E-NOTES January 2015 2015: the 30th anniversary of s. 15 of the Charter and of LEAF! The 1981 conference of the Ad Hoc Jenny Margetts, speaking at the 1981 Committee of Canadian Women and the conference Constitution (Images from Constitute!, with permission from the International Women’s Rights Project.) April 2015 brings the 30th anniversary of s. 15 of the Charter and of the founding of LEAF. Section 15 of the Charter came into effect on April 17, 1985 – three years after the Canadian Constitution and its Charter of Rights and Freedoms were enacted. Section 15 was put on hold for a three year time frame to allow federal and provincial governments to review their legislation and change any discriminatory laws. Two days later, on April 19, 1985, LEAF was founded under the leadership of women like Doris Anderson. Each of the founding mothers of LEAF had played a crucial role in ensuring women’s rights were a central component of the Charter and in Canada’s history. Plans are underway in LEAF Edmonton and by LEAF nationally for events and information outreach to celebrate these anniversaries. Page 2 of 4 Further information on the history of LEAF can be accessed at http://www.leaf.ca/about- leaf/history/. The story of women’s activism in 1981 that led to the strengthening of equality provisions in the Charter is told in the video Constitute! (see photos, above), which can be accessed at http://constitute.ca/the-film/. Further information on the Ad Hoc Committee on Women and the Constitution and the history of sections 15 and 28 of the Charter is also available as follows (although the article was written in 2001 and refers to the 20th anniversary of the 1981 conference): http://section15.ca/features/news/2001/02/06/womens_constitution_conference/ In recognition of the 30th anniversary of s. -

Branching Out: Second-Wave Feminist Periodicals and the Archive of Canadian Women’S Writing Tessa Jordan University of Alberta

Branching Out: Second-Wave Feminist Periodicals and the Archive of Canadian Women’s Writing Tessa Jordan University of Alberta Look, I push feminist articles as much as I can ... I’ve got a certain kind of magazine. It’s not Ms. It’s not Branching Out. It’s not Status of Women News. Doris Anderson Rough Layout hen Edmonton-based Branching Out: Canadian Magazine for WWomen (1973 to 1980) began its thirty-one-issue, seven-year history, Doris Anderson was the most prominent figure in women’s magazine publishing in Canada. Indeed, her work as a journalist, editor, novelist, and women’s rights activist made Anderson one of the most well-known faces of the Canadian women’s movement. She chaired the Canadian Advisory Coun- cil on the Status of Women from 1979 to 1981 and was the president of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women from 1982 to 1984, but she is best known as the long-time editor of Chatelaine, Can- ada’s longest lived mainstream women’s magazine, which celebrated its eightieth anniversary in 2008. As Chatelaine’s editor from 1957 to 1977, she was at the forefront of the Canadian women’s movement, publishing articles and editorials on a wide range of feminist issues, including legal- izing abortion, birth control, divorce laws, violence against women, and ESC 36.2–3 (June/September 2010): 63–90 women in politics. When Anderson passed away in 2007, then Governor- General Adrienne Clarkson declared that “Doris was terribly important as a second-wave feminist because she had the magazine for women and Tessa Jordan (ba it was always thoughtful and always had interesting things in it” (quoted Victoria, ma Alberta) in Martin). -

President's Letter Your New Executive Is Well Into Its Work for the Coming

RECEIVED JUN 20 1983 NATIONAL ACTION COMMITTEE on the status of women .LE COMITE NATIONAL D'AGTION sur le statut de la MEMO femme Suite 306 40 av. St.Clair est 40 St. Clair Ave. FToronto M4T 1 M9 (416) 922,3246 June, 1983 ISSN: 0712-3183 SUB: $6.00 President’s Letter Your new Executive is well into its work for the coming year, with the committees and their plans under way. We have already appeared before the Parliamentary Task Force on Pension Reform and had discussions with Donal Macdonald and some of the members of his Commission in a preliminary meeting. We’ve also had a meeting with Marc Lalonde, Minister of Finance, Judy Erola, Minister Responsible for the Status of Women, and some of the people from Monique Begin’s department of Health and Welfare, to discuss our study on Funding of Social Services for women. Over the summer, we will be working on several briefs and papers in preparation for the fall, and our Committees’ work plans are outline in this MEMO. We urge you to write us with any suggestions or input from either yourself or your group. Cheers Doris Anderson member p ~e. w~m~ the foU.omb~ ne~ me.~be~ grou~ Fredsci.e¢o~ ~/omen ' ~ C~, FredccLct:on, N. 8. K, Ltd~-~aZe,'rZoo WCA, r,~Zeke~er, O~ Oruta,~a t~u~ A~,sa~n, To~o, Or~ So~ap~t I~u~a~ o4 Reg~a, Reg., $~ehe~ ~/e~t Koote~u,j' (Uom~' ~ ~,~o~o~, ~le2.~on, B.C. WINS Tr=u,~,c~:ioa Hou,6e, T~Jl, 8.C. -

Lesbian Lives and Rights in Chatelaine

From No Go to No Logo: Lesbian Lives and Rights in Chatelaine Barbara M. Freeman Carleton University Abstract: This study is a feminist cultural and critical analysis of articles about lesbians and their rights that appeared in Chatelaine magazine between 1966 and 2004. It explores the historical progression of their media representation, from an era when lesbians were pitied and barely tolerated, through a period when their struggles for their legal rights became paramount, to the turn of the present cen- tury when they were displaced by post-modern fashion statements about the “flu- idity” of sexual orientation, and stripped of their identity politics. These shifts in media representation have had as much to do with marketing the magazine as with its liberal editors’ attempts to deal with lesbian lives and rights in ways that would appeal to readers. At the heart of this overview is a challenge to both the media and academia to reclaim lesbians in all their diversity in their real histori- cal and contemporary contexts. Résumé : Cette étude propose une analyse critique et culturelle féministe d’ar- ticles publiés dans le magazine Châtelaine entre 1966 et 2004, qui traitent des droits des lesbiennes. Elle explore l’évolution historique de leur représentation dans les médias, de l’époque où les lesbiennes étaient tout juste tolérées, à une période où leur lutte pour leurs droits légaux devint prépondérante, jusqu’au tournant de ce siècle où elles ont été dépouillées de leur politique identitaire et « déplacées » par des éditoriaux postmodernes de la mode sur la « fluidité » de leur orientation sexuelle. -

“Write It for the Women”

“Write It For the Women” Doris Anderson, the Changemaker MARY EBERTS L’auteure trace le parcours de l’activisme de Doris Anderson Those two decades were crucial in the emergence of the pendant ses deux décennies comme rédactrice en chef du maga- Canadian women’s movement. So was Doris’s leadership. zine “Chatelaine” et plus tard, comme directrice du Conseil While American women’s magazines were propagating the consultatif canadien sur la condition féminine à Ottawa. Elle confining “feminine mystique” later blasted apart by Betty décrit en détail son impact sur l’émergence des groupes de femmes Friedan,2 Doris and Chatelaine were sparking Canadian du Canada et son leadership pendant ces années. women into a knowledge of our rights, and both the desire and the will to claim our full humanity. I worked for Doris Anderson and the Canadian Advisory The year Doris assumed the editorship of Chatelaine Council on the Status of Women in 1980 and 1981, (which she later described as a “rather run-of-the-mill researching and writing about the impact on women of Canadian women’s magazine at that time”),3 Dwight Eisen- constitutional law, and the proposed new Charter of Rights.1 hauer was President of the United States, John Diefenbaker I met with Doris many times in that period, usually in a achieved a minority government in Canada, and Leslie small conference room at the Council offices. I can see her Frost had been premier of Ontario since 1949. Diefenbaker still, a blue pen in those elegant fingers, slumped over my appointed the first woman Cabinet Minister in Canada, latest draft in an attitude of resignation and frustration. -

·INSIDE 'Aging Society' Excellence-Network Network the Only One of 15 Involved with the Social Sciences

Concordia University, Montreal Vol. 14, No. 28 June 7,J990 Concordia Psychologists join ·INSIDE 'aging society' excellence-network Network the only one of 15 involved with the social sciences LAST IN A SERIES Last October 26,federal Minister ofState for Science and Technology William . , ___ ,_,,___, __ ._ Winegard announced the creation of 14 na ,,_,."'_,_,_I_ tional Networks of Centres of Excellence. About 500 researchers in 36 centres (most ly universities) will share $240 million in new federal funding over five years. A 15th network, the only one in the social Several female Concordia scien sciences, has just been announced. Concor tists contributed to this book, d_ia University is proud to be involved infour which explores the history of of the 15 projects and to play a con°tributing women in science , . Page 9 role in a fifth. Eight honorary degrees are Tim Locke awarded this year. An artist, a poet, a scientist, a political scien tist and a researcher are among· the recipients wo Concordia Psychology profes . Tannis Arbuckle-Maag Dolores Gold .. : ...... Pages 12, 13 sors ~nd members of the University's TCentre for Research in Human Development, Tannis Arbuckle-Maag and cial sciences. which· fo"ster the independence of older Dolores Gold, are contributing to Titled "Prpmoting Independence -and Canadians and increase their productivity." Nine months into her new position Concordia's growing reputation as a re Productivity irr an Aging Society," the Arbuckle-Maag and Gold ~e only two of as Vice-Rector, Academic, Rose search institution by being invited to join the network's research focus will be on normal 24 researchers from 11 universities and.two Sheinin shares her !~oughts in a wide-ranging interview newest national Network of Centres of Ex aging and, according tb the grant proposal industrial concerns, from Victoria, B.C. -

PROGRAM CORRECTIONS Please Note the Correct Spelling of the Following Names: This Program Is Available in Larger Print

Year Title Author Director 2006/2007 Radium Girls D. W. Gregory Ralph Small Canadian Kings of Repertoire Michael V.Taylor / Company Ron Cameron-Lewis Waiting for the Parade John Murrell Lezlie Wade The Maid’s Tragedy Beaumont & Fletcher Patrick Young A Chaste Maid in Cheapside Thomas Middleton Rod Ceballos 2007/2008 David Copperfield Dickens / Thomas Hischak Mimi Mekler Women of the Klondike Frances Backhouse / Company Marc Richard That Summer David French Patrick Young Pillars of Society Henrik Ibsen Heinar Piller The Trojan Women & Lysistrata Ellen McLaughlin versions Catherine McNally 2008/2009 A New Life Elmer Rice Scot Denton Murderous Women Frank Jones / Company Marc Richard Bonjour, Là, Bonjour Michel Tremblay Terry Tweed The Taming of the Shrew William Shakespeare Mimi Mekler The Taming of the Tamer John Fletcher Patrick Young 2009/2010 Widows Ariel Dorfman Bill Lane Don’t Drink the Water Brenda Lee Burke / Company Marc Richard & Suzanne Bennett Andromache Jean Racine / Richard Wilbur Patrick Young String of Pearls & The Spot Michele Lowe / Steven Dietz Ralph Small The Clandestine Marriage Garrick & Colman Peter Van Wart 2010/2011 Jane Eyre Brontë/Robert Johanson Scot Denton Child of Survivors Bernice Eisenstein/Company Ralph Small Witches & Bitches Shakespeare & Friends Kelly Straughan The Women Clare Boothe Luce Terry Tweed The Winter’s Tale William Shakespeare Mimi Mekler 2011/2012 Nicholas Nickleby Part 1 Dickens/David Edgar Peter Van Wart & Kevin Bowers 1917: The Halifax Explosion Nimbus Pub./Company Meredith Scott Goodnight Desdemona Anne-Marie MacDonald Daniel Levinson (Good Morning Juliet) Our Country’s Good Timberlake Wertenbaker Patrick Young Stage Door Ferber & Kaufman Heinar Piller 2012/2013 Semi-Monde Noël Coward Brian McKay In the Midst of Alarms Dianne Graves / Company Ralph Small The Farndale Avenue… David McGillivray & Patrick Young Production of Macbeth Walter Zerlin Jr. -

MSS2589 Vols 1--23

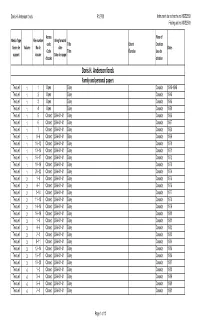

Doris H. Anderson fonds R12700 Instrument de recherche no MSS2589 Finding aid no MSS2589 Access Place of Media Type File number Bring forward code Title Extent Creation Genre de Volume No de date Dates Code Titre Étendue Lieu de support dossier Date de rappel d'accès création Doris H. Anderson fonds Family and personal papers Textuel 1 1 Open Diary Canada 1945-1949 Textuel 1 2 Open Diary Canada 1945 Textuel 1 3 Open Diary Canada 1946 Textuel 1 4 Open Diary Canada 1950 Textuel 1 5 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1966 Textuel 1 6 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1967 Textuel 1 7 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1968 Textuel 1 8--9 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1969 Textuel 1 10--12 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1970 Textuel 1 13--15 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1971 Textuel 1 16--17 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1972 Textuel 1 18--19 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1973 Textuel 1 20--22 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1974 Textuel 2 1--3 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1975 Textuel 2 4--7 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1976 Textuel 2 8--10 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1977 Textuel 2 11--13 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1978 Textuel 2 14--15 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1979 Textuel 2 16--19 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1980 Textuel 3 1--3 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1981 Textuel 3 4--6 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1982 Textuel 3 7--8 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1983 Textuel 3 9--11 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1984 Textuel 3 12--14 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1985 Textuel 3 15--17 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1986 Textuel 3 18--20 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1987 Textuel 4 1--2 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1988 Textuel 4 3--4 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1989 Textuel 4 5--6 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1990 Textuel 4 7--8 Closed 2064-01-01 Diary Canada 1991 Page 1 of 13 Doris H. -

Women and Abortion in English Canada: Public Debates And

WOMEN AND ABORTION IN ENGLISH CANADA: PUBLIC DEBATES AND POLITICAL PARTICIPATION, 1959-70 SHANNON LEA STETTNER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO NOVEMBER 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88709-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88709-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Brought Into the Discussion. This Is Followed by a Scholarly Catalogue of Each of the Sixty- One Entries in the Exhibition, Whic

BOOK REVIEWS 191 brought into the discussion. This is followed by a scholarly catalogue of each of the sixty- one entries in the exhibition, which includes an illustration, the provenance of the work, its exhibition history, a bibliography which includes archival references, and illustrations of other works by the same artist which were also in Montreal collections, followed by an essay which situates the work in the artist's career and recounts the circumstances of its acquisition by the Montreal collector. We discover, for example, that Drummond owned two studies for Daumier's Third Class Carriage (one finished version is owned by the National Gallery), one of which is owned by the National Museum of Wales; the other is unlocated. The notes (except in the catalogue essays) are in the generous margins on the same page as the text, making reference very handy. The catalogue is nicely designed and includes sixteen colour plates of the most interesting pieces. The inventory of all nineteenth-century European paintings in Montreal collections, already mentioned, is probably the most fascinating part of the catalogue. This list of over 1,400 paintings is the indication of just how discerning the tastes really were in Montreal. Of over five hundred artists of French, British and Scottish, German, Spanish, Italian, Scandinavian, and even Russian nationalities, less than one hundred have passed into the annals of art history as outstanding artists. So Montreal collectors on the whole were not all that adventurous. For the historian this list would be even more interesting had it also been organized under the name of the collector, so that each individual taste and the growth of each collection would have been revealed. -

John Reeves Fonds

MG 276 – John Reeves fonds Dates: 1962-1998 (inclusive); 1974-1977 (predominant). Extent: 95 colour transparencies; 44 colour slides; 60 photographs; textual records. Biography: John Reeves was born in Burlington, Ontario, in 1938, and graduated from the Ontario College of Art in 1961. Well known particularly for his portrait photography, Reeves’ work has appeared in virtually every Canadian periodical. His photographic and written essays have included works on Jean Vanier, Elizabeth Smart and Germaine Greer; and he provided photography for the books Debrett's Illustrated Guide to the Canadian Establishment and John Fillion - Thoughts about My Sculpture. John Reeves was a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Reeves died at Toronto in 2016. Scope and content: This fonds contains Reeves’ images of women, primarily Canadian, and involved in the arts: musicians, artists, authors, actors. Arrangement: This fonds has been arranged into the following series: A. Portraits of Women, 1974-1977. B. “30 Portraits of Women” Exhibition - 1977. C. Prints. – 1962-1998. D. Artists and Writers - Primarily West Coast. - 1977-1978, 1985. Restrictions: There are no restrictions on access. Accession Numbers: 2002-077, 2005-076. John Reeves retains copyright. Original finding aid by Cheryl Avery, 2003. Reformatting by Joanne Abrahamson, 2020. Box 1 A. Portraits of Women, 1974-1977. - 95 7x7 cm colour transparencies. Many of these portraits were originally commissioned by Lorraine Monk, then head of the NFB Still Photo Division, in part to document Canadian women of achievement during the International Year of the Woman (1975). 1. Doris Anderson. - 1975. Editor, author; Toronto. 2. Margaret Atwood. - 1975. -

Gendered Environments in Canada: an Analysis of Women and Environments Magazine, from 1976 to 1997

Gendered Environments in Canada: An Analysis of Women and Environments Magazine, from 1976 to 1997 Jessica Campbell Supervisor: Dr. Valerie Korinek Date of Defence: April 11, 2017 Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, SK Copyright Jessica Campbell, 2017. All rights reserved. Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History, Arts and Science, University of Saskatchewan, 9 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan i Abstract “Gendered Environments in Canada: An Analysis of Women and Environments Magazine from 1976 to 1997” explores feminist interpretations of environments in the Toronto-based periodical, Women and Environments (W&E).