Staff: MCS Application Received: 4/5/2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miami Condos Most at Risk Sea Level Rise

MIAMI CONDOS MIAMI CONDOS MOST AT RISK www.emiami.condos SEA LEVEL RISE RED ZONE 2’ 3’ 4’ Miami Beach Miami Beach Miami Beach Venetian Isle Apartments - Venetian Isle Apartments - Venetian Isle Apartments - Island Terrace Condominium - Island Terrace Condominium - Island Terrace Condominium - Costa Brava Condominium - -Costa Brava Condominium - -Costa Brava Condominium - Alton Park Condo - Alton Park Condo - Alton Park Condo - Mirador 1000 Condo - Mirador 1000 Condo - Mirador 1000 Condo - Floridian Condominiums - Floridian Condominiums - Floridian Condominiums - South Beach Bayside Condominium - South Beach Bayside Condominium - South Beach Bayside Condominium - Portugal Tower Condominium - Portugal Tower Condominium - Portugal Tower Condominium - La Tour Condominium - La Tour Condominium - La Tour Condominium - Sunset Beach Condominiums - Sunset Beach Condominiums - Sunset Beach Condominiums - Tower 41 Condominium - Tower 41 Condominium - Tower 41 Condominium - Eden Roc Miami Beach - Eden Roc Miami Beach - Eden Roc Miami Beach - Mimosa Condominium - Mimosa Condominium - Mimosa Condominium - Carriage Club Condominium - Carriage Club Condominium - Carriage Club Condominium - Marlborough House - Marlborough House - Marlborough House - Grandview - Grandview - Grandview - Monte Carlo Miami Beach - Monte Carlo Miami Beach - Monte Carlo Miami Beach - Sherry Frontenac - Sherry Frontenac - Sherry Frontenac - Carillon - Carillon - Carillon - Ritz Carlton Bal Harbour - Ritz Carlton Bal Harbour - Ritz Carlton Bal Harbour - Harbor House - Harbor House -

4/5/2016 CITY of MIAMI PLANNING DEPARTMENT Staff Report

Staff: MCS & TL Application received: 4/5/2016 CITY OF MIAMI PLANNING DEPARTMENT Staff Report & Recommendation To: Chairperson and Members Historic & Environmental Preservation Board From: Megan Schmitt Preservation Officer Applicant: Lynn Lewis, HEPB Member Subject: Item No. – The Babylon, 240 SE 14th Street BACKGROUND: This is a new application. On April 5, 2016, Historic and Environmental Preservation Board (HEPB) member Lynn Lewis directed Preservation Office staff to prepare a preliminary designation report for the Babylon Apartments, located at 240 SE 14th Street. The purpose of this report is to establish if there is sufficient evidence to warrant a more thorough investigation about the significance of this structure. THE PROPERTY: The Babylon is located within the lower section of Brickell in an area called Point View. Point View is located between SE 14th Street and SE 15th Road and is comprised of two semi-circular roads that form an inner and outer ring that each start at Brickell Avenue, then swing out towards the bay and return back to Brickell Avenue. Around the outer ring at the circular edge, the lots are all irregularly shaped. This irregularity allows for the structures on these parcels to be placed at an angle that provides unique and advantageous views from the units within. Acting as a primary focal point of the structure is the front façade, a stair-stepped two-dimensional wall plane constructed of concrete block that is coated in stucco, and painted a vivid red color. This façade is referred to as a “ziggurat” and it is stated that it is “reminiscent of many Dutch 17th century facades” in the text description within the catalogue produced for an exhibition of Arquitectonica’s work between 1977 and 1984. -

Public Hearing

PUBLIC HEARING Transfer of Brickell Avenue from the Florida Department of Transportation to the City of Miami From the US 1/I-95 merge/diverge ramp to SR 90/SE 8 Street PROJECT Fact SHEET PUBLIC HEARING Transfer of Brickell Avenue from the Florida Department of Transportation to the City of Miami From the US 1/I-95 merge/diverge ramp to SR 90/SE 8 Street Tuesday, January 21, 2014 6:30 p.m. - 8:30 p.m. First Presbyterian Church of Miami 609 Brickell Avenue, Miami, Florida 33131 The City of Miami Commission passed Resolution R-13-0219, dated June 13, 2013, authorizing the City Manager to execute a roadway transfer agreement with the Department. When the transfer is completed, the City will become responsible for owning, operating and maintaining Brickell Avenue within the limits of the transfer. This public hearing is being conducted to give interested persons an opportunity to express their views concerning the location, social, economic and environmental effects of the proposed transfer. Please provide your comments to ensure they become part of the project’s Public Hearing record. Persons wishing to submit written statements or other exhibits, in place of or in addition to oral statements, may do so at the hearing or by sending them to Phil Steinmiller, District Six Planning Manager, at 1000 NW 111 Avenue, Room 6111-A, Miami, Florida 33172, or via email at [email protected]. All exhibits or statements postmarked on or before February 3, 2014, will become part of the public hearing record. PUBLIC HEARING AGENDA 6:30 p.m. -

Gran Paraisobrochure Lr

EXTRAORDINARY WORKS OF ART BY PABLO ATCHUGARRY FRANK STELLA DAVID HAYES VIK MUNIZ ALEX KATZ ORAL REPRESENTATIONS CANNOT BE RELIED UPON AS CORRECTLY STATING THE REPRESENTATIONS OF THE DEVELOPER. FOR CORRECT REPRESENTATIONS, MAKE REFERENCE TO THIS BROCHURE AND TO THE DOCUMENTS REQUIRED BY SECTION 718.503, FLORIDA STATUTES, TO BE FURNISHED BY A DEVELOPER TO A BUYER OR LESSEE. Soaring high above Biscayne Bay, Paraiso’s final and most magnificent luxury condominium tower. The ultimate country club lifestyle with views beyond your imagination. Photographed on location at Paraiso Bay SEE LEGAL DISCLAIMERS ON BACK COVER “IMAGINE THE BEST IN CONTEMPORARY EUROPEAN DESIGN, A CURATED ART COLLECTION, AND SPECTACULAR AMENITIES IN A LUSHLY LANDSCAPED BAYFRONT LOCATION... THIS IS THE VISION WE HAVE BROUGHT TO LIFE AT GRANPARAISO” JORGE M. PÉREZ ARTIST’S CONCEPTUAL RENDERING ARTIST’S SEE LEGAL DISCLAIMERS ON BACK COVER DEVELOPMENT BY THE RELATED GROUP CREATORS OF GREAT NEIGHBORHOODS Founded in 1979 by Jorge M. Pérez, The Related Group is the nation’s leading developer of multifamily residences and is one of the largest Hispanic-owned businesses in the United States. Under his direction, as well as the leadership of Carlos Rosso, President of the Condominium Development Division, The Related Group and its affiliates have redefined the South Florida landscape and catalyzed the transformation of some of its most captivating neighborhoods. Following on its success with the reinvention of South of Fifth in South Beach, Brickell and Downtown Miami, The Related Group is now bringing its signature vision for the creation of lifestyle-driven communities to Edgewater. SEE LEGAL DISCLAIMERS ON BACK COVER 04 02 01. -

¨§¦4 ¨§¦75 ¨§¦95 ¨§¦10

FEDERAL HISTORIC TAX CREDIT PROJECTS Florida A total of 234 Federal Historic Tax Credit projects (certified by the National Park Service) and $198,912,921 in Federal Historic Tax Credits between fiscal year 2001 through 2020, leveraged an estimated $1,143,749,294 in total development. Data source: National Park Service, 2020 DeFuniak Springs2 ¦¨§10 Fernandina Fernandina Quincy Beach ¦¨§110 3 Tallahassee Jacksonville48 Panama City3 ¦¨§295 St. Augustine 4 Melrose Apalachicola Gainesville5 Elkton Palatka 6 Daytona Beach Ocala Deland New Smyrna Beach Inverness Sanford Longwood Orlando2 4 ¦¨§275 ¦¨§ Tampa Lakeland 40 Melbourne 2 2Lake Wales St. 3 Bartow ¦¨§95 Petersburg Vero Beach Bradenton 5 Sarasota Nokomis Venice Hobe Sound El Jobean Punta Gorda West Palm 4Beach Boca Grande 7 Belle Glade Lake Worth Fort Myers Delray Beach Fort ¦¨§75 ¦¨§5952Lauderdale Miami 1150 Miami Springs Miami Beach 7 Federal Historic Tax Credit Projects Key West 1 6 - 10 0 25 50 100 Miles R 2 - 5 11 and over Provided by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Historic Tax Credit Coalition For more information, contact Shaw Sprague, NTHP Vice President for Government Relations | (202) 588-6339 | [email protected] or Patrick Robertson, HTCC Executive Director | (202) 302-2957 | [email protected] Florida Historic Tax Credit Projects, FY 2001-2020 Project Name Address City State Year Qualified Project Use Expenditures Orman Building 32 Avenue D. Apalachicola FL 2001 $750,000 Not Reported No project name 510 S. Broadway Ave Bartow FL 2003 $115,643 -

Arquitectonica Then (1981)

Inspicio architecture The Pink House. Courtesy: Arquitectonica. Arquitectonica Then (1981) Editor’s Note: The Miami News was an evening newspaper in Miami, Florida for most of the 20th century. The paper started publishing in May 1896 as a weekly called The Miami Metropo- lis. In 1925 the newspaper moved into a new building called the Miami News Tower. This building later became famous as the Freedom Tower. The Miami News ceased publication on December 31, 1988. On Monday 12, 1981, the Miami News began publishing a five- day series of stories about Miami architecture, with the following introduction: “Beginning today and continuing through Friday, the News is publishing a series of stories about the historical development of Miami’s architecture . enjoy this glimpse of our city. It was written by architecture critic and freelance writ- er Jayne Merkel who came to our city with an experienced eye and an open mind and decided, contrary to what some wags say, there is architecture in Miami. One of Merkel’s stories was about the budding firm called Arquitectonica. The Architecture of the Future By Jayne Merkel he Miami of the future is being built on Brickell Avenue T now — but not in the way most people think. Everybody knows that the old mansions on “Millionaire’s Row” are being supplanted by new condominiums. But not everyone knows that some of those condominiums will be more signifi- cant as architecture than their pretentious predecessors were. The buildings by Arquitectonica — The Palace (1541 Brickell Ave.), The Babylon (SE 14th Street and S. Bayshore Dr.), The Atlantis (2025 Brickell Ave), The Imperial (1627 Brickell Ave.) and the Helmsley Centre (1200 S. -

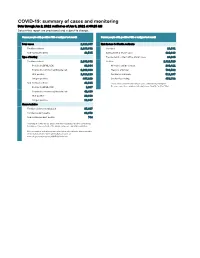

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Jun 2, 2021 Verified As of Jun 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Jun 2, 2021 verified as of Jun 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 2,329,867 Risk factors for Florida residents 2,286,332 Florida residents 2,286,332 Traveled 18,931 Non-Florida residents 43,535 Contact with a known case 920,896 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 24,985 Florida residents 2,286,332 Neither 1,321,520 Positive by BPHL/CDC 83,364 No travel and no contact 280,411 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 2,202,968 Travel is unknown 733,532 PCR positive 1,819,119 Contact is unknown 511,267 Antigen positive 467,213 Contact is pending 459,732 Non-Florida residents 43,535 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 1,037 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 42,498 PCR positive 29,688 Antigen positive 13,847 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 95,607 Florida resident deaths 36,973 Non-Florida resident deaths 744 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

Sunshine Health Comprehensive Long-Term Care Provider Directory

WELCOME TO SUNSHINE HEALTH! This is your provider directory. This directory has a list of providers you can use to get services in the Comprehensive Long Term Care program. Let us know if you need help understanding this. Interpreter services are provided free of charge to you. This includes sign language. We also have a telephone language line to help with translations. You can call Member Services. The number is 1-866-796-0530 (TTY 1-800-955-8770). These providers have agreed to provide comprehensive long term care services for you. Services will be approved by your Case Manager. You may choose any provider from this list. You may change providers at any time. If you would like to change providers, call Member Services at 1-866-796-0530 (TTY 1-800-955-8770). Some network providers may have been added or removed from our network after this directory was printed. All providers may not be taking new members. To get the most up-to-date list of Sunshine Health’s providers, call Member Services at 1-866-796-0530 (TTY 1-800-955-8770), Monday through Friday, 8:00 A.M. through 8:00 P.M., Eastern Standard Time, or visit us on the web at www.sunshinehealth.com. BEHAVIORAL HEALTH Behavioral Health refers to mental health, alcohol and drug abuse services. Sunshine Health has providers that can provide extra services. These will be in addition to the services you may already receive from Medicare or Medicaid. They are listed in this directory. Please talk to your Care Manager to arrange for these services. -

Gran Pariso Brochure- Raul Coca

Soaring high above Biscayne Bay, Paraiso’s final and most magnificent luxury condominium tower. The ultimate country club lifestyle with views beyond your imagination. Photographed on location at Paraiso Bay SEE LEGAL DISCLAIMERS ON BACK COVER “IMAGINE THE BEST IN CONTEMPORARY EUROPEAN DESIGN, A CURATED ART COLLECTION, AND SPECTACULAR AMENITIES IN A LUSHLY LANDSCAPED BAYFRONT LOCATION… THIS IS THE VISION WE HAVE BROUGHT TO LIFE AT GRANPARAISO” JORGE M. PÉREZ ARTIST’S CONCEPTUAL RENDERING ARTIST’S SEE LEGAL DISCLAIMERS ON BACK COVER 04 02 01. Icon Brickell, 2009 475 Brickell Ave. Miami, FL 33131 Tower 1: 57 Stories, 713 Units Tower 2: 57 Stories, 561 Units Tower 3 Viceroy Hotel: 50 Stories, 520 Units 02. Murano Grande, 2003 400 Alton Rd. Miami Beach, FL 33139 37 Stories, 270 Units 03. Apogee, 2007 800 South Pointe Dr, Miami Beach, FL 33139 22 Stories, 67 Units 04. Icon Bay, May 2015 460 NE 28th St. Miami, FL 33137 03 43 Stories, 299 Units The Related Group’s developments are often distinguished by groundbreaking partnerships with world-renowned architects, interior designers, and artists, resulting in residential properties that are recognized as urban landmarks. The company’s most recent distinctive properties in South Florida include One Ocean and Marea in South Beach, SLS Brickell Hotel & Residences, SLS Lux, Brickell Heights and Millecento in Brickell, and IconBay in Edgewater. Related and its leadership are committed to creating developments that energize cities, celebrate innovative architecture, and foster vibrant new ways to live in the most dynamic emerging and 01 undiscovered neighborhoods. SEE LEGAL DISCLAIMERS ON BACK COVER RESIDENTIAL INTERIORS & AMENITY SPACES BY PIERO LISSONI Italian designer and architect Piero Lissoni is internationally renowned for the design of hotels, residential complexes, corporate headquarters, yachts, and lifestyle products. -

Florida/Caribbean Architect

<.«^"_"- 4 4 :w«^v: — — -< yfor/V/tf / Caribbean ARCHIT^^;:i:::^:| ^<r^^^~^^- •CCfl •:-:->:*:•< -*-.-< -rf^^H * .* >0< •*_J* <lz* . * * * •* ~-~-~+.+ mm &&:&&£ww ->,* - * - > Design Awards Issue fall 2003 MONTHS OF CONSULTING. LAYERS OF SHOP DRAWINGS. HUNDREDS OF DIFFERENT WINDOWS. Nowadays, that's what it takes to help make something look natural. Designed to mediate between the urban and the natural, this nature center brings the look and feel of a forest to its inner-city surround- ings. That's no small feat, considering one of the project's major design challenges was trans- ferring wind loads from the extensively over- hung roof system to cedar columns without deflecting and break- ing glazing. To solve it, the Pella Commercial team worked with the architect to develop a thermally broken weeping mullion framing system that supports required spans while maintaining the center's naturalistic imagery. This is just an example of the support you can count on Pella to provide — be it providing shop drawings or simply continuing contact and support. From concep- tion through installation, Pella Commercial representatives will work with you to ensure that you meet your technical and design chal- lenges. Call your representative at 1-800-999-4868 to see what [ff^ COMMERCIAL kind ofinnovative solutions Pella has for your next design. DIVISION ©200 1 Pella Corporation DNE CLICK AND YOU'RE COVERED! The AIA Trust offers you many ways to protect yourself, your AIA Trust firm and your family. for every risk you take Simply go to www.TheAIATrust.com -

Expect a Stellar Performance

® ACTORS’ PLAYHOUSE AT THE MIRACLE THEATRE CORAL GABLES, FLORIDA Expect a Stellar Performance. “Carole is a great realtor. The proof is in the results. We closed on our historic house in Coral Gables less than two months from the date we put it on the market” — Lisa V., Seller 2019 Top Producer, Compass Florida Carole Smith Vice President [email protected] 305.710.1010 Real Estate Expertise. Insider Knowledge. Master Negotiator. Not intended to solicit currently listed property. Real estate agents affiliated with Compass are independent contractor sales associates and are not employees of Compass. Equal Housing Opportunity. Compass Florida LLC is a licensed real estate broker located at 605 Lincoln Road, 7th Floor, Miami Beach FL 33139. All information furnished regarding property for sale or rent or regarding financing is from sources deemed reliable, but Compass makes no warranty or representation as to the accuracy thereof. All property information is presented subject to errors, omissions, price changes, changed property conditions, and withdrawal of the property from the market, without notice. THE trusted community bank since 1952 Proud supporter of the Actors’ Playhouse. We have distinguished ourselves by serving our clients and our community through our rich history of banking excellence. Committed to Superior Service ◀Best Place to Work ◀ Best in Private Bank ◀Best in Community Bank ◀Best in Wealth Management CALL US! LOCATIONS 5750 SUNSET DRIVE, SOUTH MIAMI 305.667.5511 3399 PONCE DE LEON BLVD., CORAL GABLES 8941 SW 136 STREET, MIAMI www.FNBSM.com 1950 NW 87 AVENUE, DORAL Message from Executive Producing Director, Barbara S. Stein n March 18, 2020 Actors’ Playhouse was thrilled and excited to open the Lerner and Loewe musical CAMELOT on the Mainstage as part of our 2019-2020 OSeason. -

East & West Towers Can Calgary

Country City Landmark Name can calgary Art Gallery of Calgary can calgary Bankers Hall - East & West Towers can calgary Calgary Chinese Cultural Centre can calgary Calgary City Hall can calgary Calgary Exhibition & Stampede can calgary Calgary Police Service Interpretive Centre can calgary Calgary Tower can calgary Canada Olympic Park can calgary Devonian Gardens can calgary Firefighters Museum can calgary Foothills Stadium can calgary Fort Calgary can calgary Glenbow Museum can calgary Grace Presbyterian Church can calgary Lougheed House can calgary McMahon Stadium can calgary Museum of the Regiments can calgary Naval Museum of Alberta can calgary Nickle Arts Museum can calgary Olympc Hall of Fame & Museum can calgary Olympic Plaza can calgary Pengrowth Saddledome can calgary Suncor Energy Centre - West Tower can calgary Russ Boyle Statue can calgary Spruce Meadows can calgary TELUS World of Science Calgary can calgary Fairmont Palliser can calgary Uptown Stage Screen can calgary EPCOR Centre for the Performing Arts can calgary Canterra Tower can calgary TELUS Convention Centre can calgary Tribute To The Famous Five can calgary Calgary Zoo, Botanical Garden & Prehistoric Park can edmonton Commonwealth Stadium can edmonton Bell Tower can edmonton Commerce Place can edmonton EPCOR Centre can edmonton Father Lacombe Chapel can edmonton Alberta Government House can edmonton Rutherford House can edmonton City Hall can edmonton Oxford Tower can edmonton TD Tower, Edmonton can edmonton Manulife Place can edmonton Telus Plaza South can edmonton