2020 Grade 6 Summer Reading Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Guidance Lyrics

No Guidance Lyrics Before I die I'm tryna f_ck you, baby Hopefully we don't have no babies I don't even wanna go back home Hopefully, I don't leave you on your own Ayy Trips that you plan for the next whole week Bands too long for a nigga so cheap And your flex OD, and your s_x OD You got it, girl, you got it (Ayy) You got it, girl, you got (yeah) Pretty lil' thing, you got a bag and now you wilding You just took it off the lot, no mileage Way they hittin' you, the DM lookin' violent Talkin' wild, you come around and now they silent Flew the coop at seventeen, no guidance You be staying low but you know what the vibes is Ain't never got you nowhere being modest Poppin' shit but only 'cause you know you're popping You got it, girl, you got it (Ayy) You got it, girl, you got it Lil' baby in her bag, in her Birkin No nine to five put the work in Flaws and all, I love 'em all, to me, you're perfect Baby girl, you got it, girl, you got it, girl You got it, girl, you got it, girl (Ooh) I don't wanna play no games, play no games F_ck around, give you my last name Know you tired of the same damn thing That's okay 'cause, baby, you You got it, girl, you got it (Ayy) You got it, girl, you got it You the only one I'm tryna make love to, Picking and choosing They ain't really love you, runnin' games, usin' All your stupid exes, they gon' call again Tell 'em that a real nigga steppin' in Don't let them niggas try you, test your patience Tell 'em that it's over, ain't no debating All you need is me playin' on your playlist You ain't gotta be frustrated -

The Big Urban Game, Re-Play and Full City Tags Art Game Conceptions in Activism and Performance

The big urban game, re-play and full city tags Art game conceptions in activism and performance MARGARETE JAHRMANN The practice of technological tagging of locations in contemporary urban spaces can be seen in relation to the concept of the ‘Re-Play’ of urban space and urban life using performance practices. The performance of technological play with mobile technologies in everyday life serves as the starting point for a new inter- pretation of modern cities as a positive utopia. Re-Play is introduced in this pa- per as an idea of staging knowledge. In my approach to performance, I consider play a method to identify topographies of cultural or historic interest in urban spaces and to frame potential inter-action on such sites. Play consequently ena- bles the extraction of new stories and new knowledge concerning narratives of the urban. The idea of Re-Play draws on the Situationist principle developed in the 1960s (Constant 1972), of a playful and open society living in a ‘New Baby- lon’ that offers zones of play and relaxation as a basis for creativity and a self- determined life – in relation to and through the constructivist use of technolo- gies. Contemporary activist play and performative urban games have to deal with a specific precondition: the electronic, electromagnetic and logic topography of the modern city, which is marked through ‘tags’. Tagging can be understood in two ways, first as an expression of an urban sub-culture of graffiti arts and sec- ondly as a technological term to indicate a virtual-reality marker in physical space. -

TOURNAMENT RULES Inclement Weather Policy SJ Warriors Contact Numbers Are Listed at the End of the Rules

SJ Warriors TOURNAMENT RULES Inclement Weather Policy SJ Warriors contact numbers are listed at the end of the rules. In the event of rain, we will do everything within our power to make up games and stay as close to the original game schedule as possible. However, there may be circumstances in which we will need to deviate from the printed schedule. When this occurs, we will use the following procedures as a guide: Our first priority will always be the safety of each individual at the facility. If inclement weather forces a cancellation of game slots during pool play rounds, we may have to alter the brackets to complete the tournament. If a pool play game cannot be played, the team with the higher seed will advance. SJ WARRIORS will not name a champion of the tournament without a championship game. If rain comes into play, we will do everything we can do to stay close to the original game schedule. • Play No Games - $100 administrative cost is non-refundable. • Play 1 Game - Receive a 50% refund. • Play More Than 1 Game – No refund. Note: Once a game starts it will count as a game played, regardless of its length. Suspended Games Games that do not make it to regulation (3 complete innings for a 6 inning game or 4 complete innings for a 7 inning game) due to weather / darkness will be considered a suspended game and will be resumed (if possible) from the point of suspension at the earliest time available. If there is not enough time to resume the game, it will be considered a complete game at the end of the last complete inning and the team that is winning at that point will be the winner. -

Earthlings, Meet Venus” Informational Text and Questions

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.2 Determine two or more central ideas in a text and analyze their development over the course of the text CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.3 Analyze the interactions between individuals, events, and ideas in a text (e.g., how ideas influence individuals or events, or how individuals influence ideas or events). CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.6 Determine an author's point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author distinguishes his or her position from that of others. “Earthlings, Meet Venus” Informational Text and Questions Due: Friday, May 29th Directions: Read the informational text “Earthlings, Meet Venus”, and answer the questions that follow. EARTHLINGS, MEET VENUS 7th GradeLexile: 1100 by Rachel Slivnick 2018 In this informational text, Rachel Slivnick describes one of the planets in our Solar System, Venus. As you read, take notes on Venus’ environment. "Size comparison of Venus and Earth. Approximate scale is 29 km/px." by NASA is in the public domain. [1] What are your neighbors like? Chances are you have some friendly neighbors, some quiet neighbors, and some people who live on your block that are downright weird and maybe even a little CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.2 Determine two or more central ideas in a text and analyze their development over the course of the text CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.3 Analyze the interactions between individuals, events, and ideas in a text (e.g., how ideas influence individuals or events, or how individuals influence ideas or events). CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.6 Determine an author's point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author distinguishes his or her position from that of others. -

Danger Ahead

DANGER AHEAD FOR THE SOCIALIST PARTY IN PL.4YING THE GAME OF POLITICS 7 3 EUGEN& DEBS AND CHARLES EDWARD RUSSELL Price, 5 cents; 10 for 20 cents; $1.00 a hundred; $7.00 a thousand CHICAGO 7RARLES H. KERR & CXMPASY 118 West Kinzie Street FOREWORD. Th.e two articles herein republished first appeared in the International Socialist Re- view, the former in January and the latter in September, 1911. Both of them causd wide comment, both favorable and unfavor. abie. The Socialist movement develops itsi revolutionary character and clarifies it purposes by constant self-criticism. An, democratic organization can be properly regulated only by the frankest and freest dis-;lssion of its problems on the part of its membership. The contents of this book- let have a peculiar value for the SociaIist movement of America just at present. They demonstrate and emphasize the utter impotency of compromise. The labor par- ties of England and Australasia have proven themselves miserable failures. The revolutionary message which Marx ana Engels stated as a scientific principle, Debs and Russell herein deliver from the actual field of the class struggle. DANGER AHEAD. BT ECTGESE V. DEBS. The large increase in the Socialist vote in the late national and state elections is quite naturally hailed with elation and re- joicing by party members, but I feel prompted to remark, in the light of some personal observations during the campaign, that it is not entirely a matter of jubilation. I am not given to pessimism, or captious criticism, and yet I cannot but feel that some of the votes placed to our credit this year were obtained by methods not consis- tent with the principles of a revolutionary party, and in the long run will do more harm :han good. -

MCNAIR.Thesis.July 16.FINAL

THE HISTORY OF KAKAWANGWA by Kristen McNair A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 2012 THE mSTORY OF KAKAWANGW A by Kristen. MeN air This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Professor Andrew Furman, Department of English, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. AndrewThriAdVisor Furman, Ph.D. Ayse 'r:t{tBU~ Johnnie Stover, Ph.D~ Heather Coltman, D .M.A. Interim Dean, The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts & Letters B!r7;ss":pr!---. Dean, Graduate College 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the professors who worked with me on this project: Dr. Andrew Furman, Ayse Papatya Bucak, and Dr. Johnnie Stover. Your feedback regarding my writing and my novel has been invaluable. Thank you for the encouragement and for requiring my very best. To mom, Tory, my siblings, and extended family and friends, you encouraged me to embrace my identity as a storyteller. Thanks to Robert Olen Butler, Melvin Sterne, Paul Shepherd, and Elizabeth Stuckey- French for teaching me how to write fiction in the first place. Thanks to my loving husband and daughter, for allowing me to ignore the world and write this novel. -

1St Annual Berlin Brawl Tournament

Colossal Sports Academy 2021 Tournament Rules Tournament Fee and format Fee: 8U - $375 9U thru 12U - $495 13U & 14U - $595 15U/16U - $625 Guaranteed 3 games (weather permitting) Inclement Weather Policy In the event of rain, we will do everything within our power to make up games and stay as close to the original game schedule as possible. However, there may be circumstances in which we will need to deviate from the printed schedule. If and when this occurs, we will use the following procedures as a guide: • our first priority will always be the safety of each individual at the facility. • if inclement weather forces a cancellation of game slots; we may have to alter the brackets to complete the tournament. If a game cannot be played, the team with the higher seed will advance. • a champion of the tournament will not be named without a championship game. Suspended Games Games that do not make it to regulation (4 complete innings for a 6-inning game; 5 innings for a 7 inning game) due to weather / darkness will be considered a suspended game and will be resumed (if possible) from the point of suspension at the earliest time available. If there is not time to resume the game, it will be considered a complete game at the end of the last complete inning and the team that is winning at that point will be the winner. Game not suspended if time limit has expired. Weather Related Refund Policy • Play No Games (Receive full credit for a future tournament or Full refund less a $100 Administrative fee • Play only 1 Game (Receive a credit or refund of tournament fee less $200 Administrative fee) • Play 2 games (no refund) Note: Once a game starts it will count as a game played, regardless of its length. -

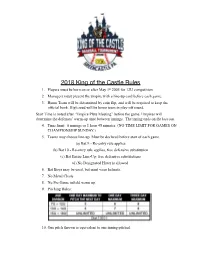

2018 King of the Castle Rules Copy

2018 King of the Castle Rules 1. Players must be born on or after May 1st 2005 for 12U competition 2. Managers must present the umpire with a line-up card before each game. 3. Home Team will be determined by coin flip, and will be required to keep the official book. High seed will be home team in play-off round. Start Time is noted after “Umpire Plate Meeting” before the game. Umpires will determine the defenses’ warm-up time between innings. The inning ends on the last out. 4. Time limit: 6 innings or 1 hour 45 minutes (NO TIME LIMIT FOR GAMES ON CHAMPIONSHIP SUNDAY.) 5. Teams may choose line-up. Must be declared before start of each game. (a) Bat 9 - Re-entry rule applies (b) Bat 10 - Re-entry rule applies, free defensive substitution (c) Bat Entire Line-Up: free defensive substitutions (d) No Designated Hitter is allowed. 6. Bat Boys may be used, but must wear helmets. 7. No Metal Cleats 8. No Pre Game infield warm up. 9. Pitching Rules: 10. One pitch thrown is equivalent to one inning pitched. 11. Pitcher: Manager has 1 free trip to the mound each inning. The 2nd trip pitcher must be removed. Once a pitcher is removed, they cannot return to the mound in that game. 12. Pitching cards will be kept for each game. Home team will be responsible to log innings pitched for both teams. At the completion of the game, both managers will initial the pitching card that they agree with the total innings pitched by their team. -

CHAPTER 10 ONLY Revised August 24, 2020

US CHESS FEDERATION’S OFFICIAL RULES OF CHESS 7TH EDITION FREE DOWNLOAD VERSION: CHAPTER 10 ONLY Revised August 24, 2020 Tim Just, Chief Editor US Chess National Tournament Director FIDE National Arbiter 2 Contents Chapter 10: Rules for Online Tournaments and Matches .................................................................4 1. Introduction. ..........................................................................................................................4 1A. Purview. .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1B. Online Tournaments and Matches. ..................................................................................................... 4 2. The US Chess Online Rating System. ........................................................................................4 2A. Online Ratings and Over-The-Board (OTB) Ratings. ............................................................................. 4 2B. Ratable Time Controls for Online Play. ................................................................................................ 4 2C. US Chess Rating System and FIDE Rating System. ................................................................................ 5 2D. Calculating Player Ratings. .................................................................................................................. 5 2E. Assigning Ratings to Unrated Players. ................................................................................................. -

The Newtown Classic Tournament Rules U13, U14, U15, U18 Updated 9/25/2015

The Newtown Classic Tournament Rules U13, U14, U15, U18 Updated 9/25/2015 PAYMENT/WEATHER RELATED REFUND POLICY Full payment must be received by the date listed on the Tournament Registration website page. Absolutely no refunds/credits for any reason will be given for withdrawals within thirty days of tournament start date. Three game minimum tournaments will have the following weather-related refunds/credits: Play NO games: Full refund Play 1 game: $150 credit for next year’s tournament only or refund Play 2 games: $75 credit for next year’s tournament only (no refund – credits cannot be combined for any new registration.) INSURANCE Each team is required to carry its own insurance and submit a certificate of insurance to CRNAA prior to the beginning of the tournament. No team will be allowed to play until we have that information and it is verified. The certificate must have the following entities listed as “additional insured”: Council Rock Newtown Athletic Association Newtown Township Newtown Borough Council Rock School District The Certificate Holder will be CRNAA, PO Box 173, Newtown PA 18940. This can be obtained by simply calling your insurance company and asking them to provide a certificate. OFFICIAL GAME/RESCHEDULED GAMES/PROTESTS All games played at The Newtown Classic are Official at the end of ONE (1) complete inning, regardless of age or reason for the stoppage (weather, darkness, etc.) This ruling is in place due to the time constrictions of weekend pool play. All age groups shall play 7-inning games. A team must have 9 players ready to play by the start of their game time as determined by Tournament schedule. -

Synopsis Radio Golf, August Wilson's Last Play, Is Also the Last Play

RADIO GOLF Synopsis Radio Golf, August Wilson’s last play, is also the last play chronologically in his famous Pittsburgh Cycle. In the play we find Harmond Wilks, a man who discovers both himself and the place that birthed him at a crossroads. On the verge of an almost-guaranteed win as a mayoral candidate, Wilks finds his identity shaken when his morals and ideals are questioned by those around him. Ultimately, he must recognize what the price of his success is and decide whether he is willing to pay it. Characters ELDER JOSEPH “OLD JOE” BARLOW: Recently returned to the Hill District where he was born in 1918. Although ostensibly as harmless as he is homespun, his temperament belies a life checkered by run-ins with the law and a series of wives. He sees and calls things plainly, requires little and seeks only harmony. HARMOND WILKS: Real-estate developer seeking mayoral candidacy. He grew up a privileged and responsible son of the Hill District and intends to bring the neighborhood back from urban blight through gentrification, while making a fortune in the process. He cares about the city of Pittsburgh, the neighborhood and its people, but is caught between what is politically expedient and what is morally and ethically just. ROOSEVELT HICKS: Bank vice president and avid golfer, as well as Harmond’s business partner and college roommate. Roosevelt is preoccupied with his financial status and getting green time. He values the end result of a transaction more than the practical or spiritual virtues of a job well done. -

The Championship Program

The Championship Program Throwing Period—Jan. 10 | 1st Team Practice—Jan. 31 | 1st Contest—Feb. 17 Online Requirements For All Sports POSTING SCHEDULES Schools must post season schedules on the AHSAA website in the Members’ Area by the deadline dates listed below. Failure to do so could result in a fine assessed to the school. Schools may go online and make any changes immediately as they occur. Deadlines for posting schedules: May 1 — fall sports (football only) June 1 — fall sports (cross country, swimming & diving, volleyball) Sept. 15 — winter sports (basketball, bowling, indoor track, wrestling) Jan. 15 — spring sports (baseball, golf, outdoor track, soccer, softball, tennis) POSTING ROSTERS Schools are required to post team rosters prior to its first contest of the season. POSTING SCORES Schools are also required to post scores of contests online immediately following all contests in the regular season (and within 24 hours after regular season tournaments) and in the playoffs or be subject to a fine. In the post-season playoffs, failure to report scores immediately after a contest will subject the school to a fine. 1. The baseball program provides for competition in seven classes—1A, 2A, 3A, 4A, 5A, 6A and 7A. Classes 1A-6A are divided into 16 areas. 7A is divided into 8 areas. Championship play shall be on a play-at-home basis. Every school fielding a team must play in the cham- pionship program. 2. Each high school is permitted 28 varsity/junior varsity games (1A-6A), 32 games (7A) during regular season excluding games played during “Spring Break.” Each junior high or middle school is permitted 24 regular season (26 for 7A) games excluding games played during “Spring Break.” The Baseball Committee recommends that a team play a minimum of 12 regular season games prior to the playoffs.