For Peer Review1 19 Number of Peers Who Added Some Critical Insights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bonaire Reporter Columnist Siomara Albertus with Her Mother, Fabric Artist Maria Johnita "Jo" Albertus-Marcera, at Dia Di Arte

P.O. Box 407, Bonaire, Netherlands Antilles, Phone 790-6518, 786-6125, www.bonairereporter.com email: [email protected] Since 1994 Printed every fortnight On-line every day, 24/7 Bonaire Reporter columnist Siomara Albertus with her mother, fabric artist Maria Johnita "Jo" Albertus-Marcera, at Dia di Arte. Bonaire Reporter- July 16-30, 2010 Page 1 he Police Dutch Table of Contents Bonaire Government photo Traffic Minister of T This Week’s Stories Department Transport recorded 368 Camiel Runway repair 2 collisions in Eurlings Power Plus For Bonaire II -Pollution 3 the first six (right in Yes/No/Nothing-Referendum 3 month of 2010, more or less two photo) Preserving Island Culture-Papiamentu 3 a day. There were 92 injuries, launched the Parrot watch-Hard Times for chicks 6 two of them serious, but no renovation Weight Loss Winners –Tina Woodley 6 Letters to the Editor-Crime Lament 7 deaths. Most of the accidents of the Fla- were because drivers did not Internet photo In Memorium-Albert Romijn 8 mingo Air- Posada Para Mira 8 maintain a proper distance be- port run- Dia di Arte-Art Day– 18th 10 tween vehicles and couldn’t stop ceremony to dismantle the way on Essence Opens 11 in time. Country of the Netherlands Monday, Soccer Training f for Kids 11 Thirty-four of the incidents were Antilles on October 10. The July 5. Groupers Eat Lionfish 11 “hit and run,” and 14 of these royal couple announced this dur- The renova- Sebiki Winners at Mangazina 11 were solved by the Traffic De- ing the customary annual gather- tion is a Miss Bonaire Beach Pageant 15 partment. -

Traditionele Muziek Zit in Mijn Bloed!

Traditionele muziek zit in mijn bloed! Een studie naar de verbeelding van een nieuwe politieke status in traditionele muziek op Curaçao en St. Eustatius. Curaçao Sint Eustatius Jennifer Groeneveld en Naomi Hortencia Bachelor Scriptie Culturele Antropologie Universiteit Utrecht Juni 2013 Traditionele muziek zit in mijn bloed1 Een studie naar de verbeelding van een nieuwe politieke status in traditionele muziek op Curaçao en St. Eustatius. Curaçao Sint Eustatius Jennifer Groeneveld en Naomi Hortencia 3536165 3216241 [email protected] [email protected] 28 juni 2013 Begeleidster: N. van der Heide Universiteit Utrecht 1 Uitspraak van Edward, tumbamusicus, op Curaçao. “Traditionele muziek zit in mijn bloed, omdat ik het heb meegekregen van mijn voorouders.” Titelvertaling in het Papiamentu: Musiká tradishonal ta den mi sanger. Titelvertaling in het Engels: Traditional music is in my blood. Afbeelding 1: Gemaakt door Thuraia, vriendin van Jennifer Groeneveld, woonachtig op Curaçao (febr. 2013) van carnavalsband Cache tijdens de Gran Marcha op Curaçao. Afbeelding 2: St. Eustatius gemaakt door Naomi Hortencia van leden van de Killy Killy Band die voor the Culture Tea Party hun snaarinstrumenten aan het stemmen zijn (24 februari 2013). Afbeelding 3: Vlag Curaçao http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Cura%C3%A7ao.svg Geraadpleegd: juni 2013 Afbeelding 4: Vlag St.Eustatius http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Sint_Eustatius.svgGeraadpleegd: juni 2013 2 INHOUDSOPGAVE pagina Voorwoord 5 Kaarten 7 Inleiding 9 1 Theoretisch kader 16 Inleiding 16 1.1 Slavernij en Racisme 16 1.2 Nieuwe politieke status 18 1.3 Autonomie en onafhankelijkheid 20 1.4 Popular Culture 21 1.5 Space and Place 23 1.6 Caribische en traditionele muziek 24 1.7 Carnaval 26 2 Context 27 Inleiding 27 2.1 Politieke veranderingen 27 2.1.1 Curaçao 27 2.1.2 St. -

Caribbean 3.0

Caribbean 3.0 This work is published by: Uitgeverij Eigen Boek B.V., Hoofddorp - Netherlands www.uitgeverijeigenboek.nl [email protected] Copyright, © 2013 Miguel Goede All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be re- produced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ISBN 978-94-6129-122-6 Caribbean 3.0 Transforming Small Island Developing States Dr. Miguel Goede June 2013 Uitgeverij Eigen Boek B.V. | Hoofddorp Dedicated to my parents Contents Start 3.0 right away 11 1. Introduction 13 Talk show 13 Why CSIDS 3.0? 14 What's in a name? 16 Christmas 2012 17 5 May 2013 20 2. 3.0 22 The principles of 3.0 25 Generation 3.0 30 Democracy 3.0 33 3. Capitalism 3.0: The End of Capitalism 2.0 (As We Knew It) 36 The history of capitalism 40 A brief account of the recent history 40 A more philosophical approach 44 Analysis 49 Possible solutions to the crisis 52 Concluding remarks 53 4. Storytelling 54 Story Curaçao 54 5. The CSIDS 59 Anguilla 65 Antigua and Barbuda 65 Aruba 66 Bahamas 66 Barbados 67 Belize 68 British Virgin Island 69 Cuba 69 Dominica 70 Dominican Republic 71 Grenada 72 Guyana 72 Haiti 72 Jamaica 73 Montserrat 73 Netherlands Antilles 73 Puerto Rico 75 St. -

2013 Niscuracao EN.Pdf

Transparency International is the global civil society organisation leading the fight against corruption. Through more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we raise awareness of the damaging effects of corruption and work with partners in government, business and civil society to develop and implement effective measures to tackle it. Authors: P.C.M. (Nelly) Schotborghchotborgh--vanvan dede VenVen MscMsc CFECFE andand Dr. S. (Susan) van Velzen © Cover photo: Flickr/Jessica Bee Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believedbelieved toto bebe correctcorrect asas ofof XXXJune 2013. 2013. Nevertheless, Nevertheless, Transparency Transparency InternationalInternational cannotcannot accept accept responsibility responsibility for for thethe consequencesconsequences ofof itsits useuse forfor otherother purposespurposes oror inin otherother contexts.contexts. ISBN:ISBN: 978978--33--943494349797--3535--99 Printed on Forest Stewardship Council certifiedcertified paper.paper. © 2013 Transparency International. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION 2 II. ABOUT THE NATIONAL INTEGRITY SYSTEM ASSESSMENT 5 III. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 13 IV. COUNTRY PROFILE: FOUNDATIONS FOR THE NATIONAL INTEGRITY SYSTEM 19 V. CORRUPTION PROFILE 27 VI. ANTI-CORRUPTION ACTIVITIES 31 VII. NATIONAL INTEGRITY SYSTEM 1. LEGISLATURE 35 2. EXECUTIVE 54 3. JUDICIARY 72 4. PUBLIC SECTOR 84 5. LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES 103 6. ELECTORAL MANAGEMENT BODY 118 7. OMBUDSMAN 129 8. SUPREME AUDIT AND SUPERVISORY INSTITUTIONS (PUBLIC SECTOR) 141 9. ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCIES 158 10. POLITICAL PARTIES 160 11. MEDIA 173 12. CIVIL SOCIETY 185 13. BUSINESS 195 14. SUPERVISORY INSTITUTIONS (PRIVATE SECTOR) 208 VIII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 230 IX. ANNEX 242 I. -

The Development of a Caribbean Island As Education Hub

Master Thesis The Development of a Caribbean Island as Education Hub The Case of Curacao Daniel Lohmann September 2015 University of Twente Daniel Lohmann I Master Thesis I University of Twente General Information Student: Daniel Lohmann University of Twente Business Administration Track: Financial Management Date of publication: Osnabrück, 24th September 2015 First supervisor: M.R. Stienstra (MSc) NIKOS / BMS/ University of Twente International Entrepreneurship & Management Second supervisor: Prof. Dr. P. B. Boorsma University of Twente Department of Public Administration Number of pages/words: 114 / 40,128 II Daniel Lohmann I Master Thesis I University of Twente Preface In some way, a thesis about a small island in the Caribbean seems to be unusual in connection with the studies of Business Administration but it fits perfectly to my studies content and my desire to learn more about the internationalized world, bringing me one step closer towards goal to work in an international environment. I wanted to gain further knowledge regarding the world’s economy and its interconnected relations. During the last six years, I had the chance of traveling a lot and studying abroad, leaving me with many different impressions and experiences that developed my own character. After all this time, I had to find out how to complete my studies while connecting the current content of Business Administration with my interests. The solution was found after contacting the chair of Innovation & Entrepreneurship, who currently has a high interest in collaboration with students, representatives and experts concerning the economy of the Caribbean Islands. The topic given to me was initially looking at Curacao as a logistic hub for Latin America and Europe and had its focus on trade barriers and trade agreements. -

1 the Global Financial Crisis and Its Aftermath: Economic and Political

The global financial crisis and its aftermath: economic and political recalibration in the non-sovereign Caribbean Abstract in English The small non-sovereign island jurisdictions (SNIJs) of the Caribbean have a privileged position in the global political economy, with significant political and economic autonomy on the one hand, and useful protections and support structures provided by their metropolitan powers on the other. However, the global financial and economic crisis of 2007-2008 highlighted starkly some of the fragilities of this privileged status—in particular their economic vulnerability and the unequal and often fractious relationship with their metropolitan powers. This article considers the British, Dutch, French and United States jurisdictions and the short and longer-term impacts of the crisis. The article’s key concern is to assess the extent to which the instability in the global economy over the last decade has affected both the economic and political dynamic of these jurisdictions, and to what extent their unique position in the global political economy has been compromised. Abstract in Spanish Las pequeñas jurisdicciones no soberanas del Caribe (SNIJs) del Caribe, tienen una posición privilegiada en la economía política global. De un lado gozan de autonomía política y económica significativa, y del otro gozan de protecciones y estructuras de apoyo provistas por sus metrópolis. No obstante, la crisis financiera global de 2007-08 hizo evidente algunas de las fragilidades de este status privilegiado—en particular su vulnerabilidad económica y su relación desigual y fragmentada con sus poderes metropolitanos. Este artículo considera las jurisdicciones inglesas, holandesas, francesas y estadounidenses y los impactos de la crisis a corto y largo plazo. -

Bonaire/Kralendijk

P. O. Box 407, Bonaire, Dutch Caribbean, Phone 786-6518, 786-6125, www.bonairereporter.com email: [email protected] Since 1994 Bonaire/Kralendijk – passing, the smallest-ever lion fish was caught.) The photo- n Sunday, May 12, about 20 experienced volunteers graph shows the bunch of tired and satisfied volunteers after O joined the activities of the Fishing Line Project, a divi- the recovery dive. The author, more or less in the middle of sion of the STCB (Sea Turtle Conservation Bonaire). They the photo, held firm by STCB Coordinator Mabel Nava, dis- met at the Dive Inn, one of the many locations of Dive plays the broken plate with the smallest lion fish ever. But Friends Bonaire, which provided free air fills to the SCUBA let’s take life seriously. But not too seriously. After the recov- divers, to plan a major elimination of discarded fishing line ery dive all volunteers were invited for a tasty sandwich from the Town Pier area. lunch aboard the Freewinds. Sue Willis from the Fishing Line Project had finally re- Good job, volunteers! Thank you, Freewinds. And thank ceived permission from the Harbormaster and the cruise ship you again Dive Friends Bonaire for the supply of free air, the Freewinds to remove as much new or newish fishing line as location and fresh water to rinse the diving gear. We pre- possible from the underwater world. sumably can’t save this world, but at least we can make it Weather conditions and water temperature were optimal– better. Let’s continue tilting at the windmills. -

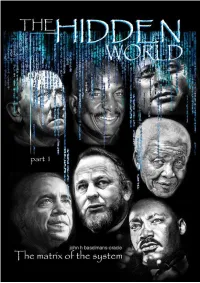

THE HIDDEN WORLD -The Matrix of the System

THE HIDDEN WORLD -The Matrix of the system- Part 1 John H. Baselmans - Oracle Curaçao, 2015 This book is written / compiled by John H Baselmans-Oracle Layout and drawings by John H Baselmans-Oracle Free translation: Amy Mcintosh and Jeffrey Josef With special thanks to those people who have helped me. Copyrights Included all writers who have contributed to this anthology. This reference is to show from the widest possible spectrum, how the matrix of this system works. Personally I do not believe in these rights because as a free man of flesh and blood you own nothing. ISBN 978-1-326-03644-7 THE HIDDEN WORLD -The Matrix of the system- Part 1 - Whether it is the criminal or rapist in the neighborhood - Or the murderer who is still out there. - Or the police, the courts or the judiciary abusing their power. - Or Politicians - Presidents or royal houses who claim to be inviolable. - Or the faiths with their churches and their popes high on a throne. They play the game of the matrix, which is ordered, the game where they are enslaved and know no way out. Don’t be upset, have no feelings of revenge and see them as weak pitiable energies who do not know the way out and still wandering in a suppressed matrix. Fear and revenge are not the tools to show these people differently. Act as a human being, connected to the absolute, don’t allow them affect your life in their search in a choked matrix. Namasté john from the baselmans-oracle family - The matrix of the system part 1 5 INDEX -The hidden world- Part 1- Introduction 24 CHAPTER 1 Public opinions and letters 26 1-1 Who is john h. -

Curaçao, Our Nation

! ! ! Curaçao, our nation ! !"#!$$%&'()*(+&#,"-.(%/#0"#*1.*.%#3.%)4)0#! ! "#$%&!'()(*+! ! Master Thesis Research Master Public Administration and Organisational Science Utrecht University 1 Title Curaçao, our nation An Appreciative Inquiry on the future of Curaçao Date Utrecht, September 2011 Master Research Master in Public Administration and Organisational Science Utrecht School of Governance Utrecht University Author Joeri Kabalt Student number: 3065642 Stroomstraat 35, 3513 VM Utrecht, The Netherlands [email protected] Supervisors Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Dian Marie Hosking Second Reader: Prof. Dr. Arjen Boin Cover Painting by Nena Sanchez, www.nenasanchez.com 2 Table of contents ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................... 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER 1: BEGINNINGS OF A JOURNEY .............................................................. 10 1.1 TRAVELLING TO CURAÇAO ........................................................................................... 10 A MENTALITY CHANGE? ............................................................................................................................................ 11 YOU ARE A HUMAN! .................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.2 DEVELOPING AN INTEREST IN APPROACHES TO DEVELOPMENT -

Peeters, Bernd 1.Pdf

Hugo Chávez A threat to the Netherlands Antilles? B. Peeters Human Geography Master specialisation “Conflicts, Territories & Identities” Radboud University Nijmegen Supervisor: Dr. B. Bomert Department of Human Geography Nijmegen, October 2011 1 Executive Summary The main research question that is being discussed in this thesis is: ‘What is Chávez’ rationale for uttering provocative remarks concerning the United States of America and The Netherlands?’ In order to come to a feasible answer to the main research question, there will be made use of both discourse analysis and the Post Colonialism theory. In addition to finding an explanation for Chávez provocative discourse, this thesis also analyses whether these provocative statements are just discourse, or if Chávez is also able to support and underpin his discourse with actual deeds or actions. Another reason for not only focussing on Chávez’ discourse, but also on his actions or deeds is to satisfy the main critique on Post Colonialism theory, namely that it is too much focussed on just discourse and to a certain extent ignores the actions or deeds that often accompany the discourse. The analysis shows that Chávez is certainly able to support his discourse with convincing actions or deeds. Regarding the main research question it appeared that the rationale for his provocative remarks should not be seen as an assault primarily focussed on The Netherlands or the Netherlands Antilles itself. On the contrary it should be seen as part of the bigger, overarching metier of Chávez denigrating and being critical about the United States. This metier of being critical about the United States comes forth out of a feeling of being surrounded by the US (military) presence in the countries neighbouring Venezuela as well as by means of the US Navy Fourth Fleet patrolling the sea area nearby Venezuela.