Invertebrates of the Imperial Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biscuit Clypeaster Subdepressus (Echinodermata: Clypeasteroida)

Embryonic, Larval, and Juvenile Development of the Sea Biscuit Clypeaster subdepressus (Echinodermata: Clypeasteroida) Bruno C. Vellutini1,2*, Alvaro E. Migotto1,2 1 Centro de Biologia Marinha, Universidade de Sa˜o Paulo, Sa˜o Sebastia˜o, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil, 2 Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biocieˆncias, Universidade de Sa˜o Paulo, Sa˜o Paulo, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil Abstract Sea biscuits and sand dollars diverged from other irregular echinoids approximately 55 million years ago and rapidly dispersed to oceans worldwide. A series of morphological changes were associated with the occupation of sand beds such as flattening of the body, shortening of primary spines, multiplication of podia, and retention of the lantern of Aristotle into adulthood. To investigate the developmental basis of such morphological changes we documented the ontogeny of Clypeaster subdepressus. We obtained gametes from adult specimens by KCl injection and raised the embryos at 260C. Ciliated blastulae hatched 7.5 h after sperm entry. During gastrulation the archenteron elongated continuously while ectodermal red-pigmented cells migrated synchronously to the apical plate. Pluteus larvae began to feed in 3 d and were *20 d old at metamorphosis; starved larvae died 17 d after fertilization. Postlarval juveniles had neither mouth nor anus nor plates on the aboral side, except for the remnants of larval spicules, but their bilateral symmetry became evident after the resorption of larval tissues. Ossicles of the lantern were present and organized in 5 groups. Each group had 1 tooth, 2 demipyramids, and 2 epiphyses with a rotula in between. Early appendages consisted of 15 spines, 15 podia (2 types), and 5 sphaeridia. -

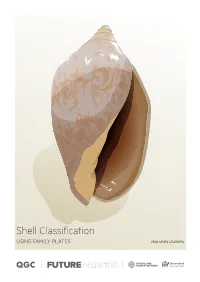

Shell Classification – Using Family Plates

Shell Classification USING FAMILY PLATES YEAR SEVEN STUDENTS Introduction In the following activity you and your class can use the same techniques as Queensland Museum The Queensland Museum Network has about scientists to classify organisms. 2.5 million biological specimens, and these items form the Biodiversity collections. Most specimens are from Activity: Identifying Queensland shells by family. Queensland’s terrestrial and marine provinces, but These 20 plates show common Queensland shells some are from adjacent Indo-Pacific regions. A smaller from 38 different families, and can be used for a range number of exotic species have also been acquired for of activities both in and outside the classroom. comparative purposes. The collection steadily grows Possible uses of this resource include: as our inventory of the region’s natural resources becomes more comprehensive. • students finding shells and identifying what family they belong to This collection helps scientists: • students determining what features shells in each • identify and name species family share • understand biodiversity in Australia and around • students comparing families to see how they differ. the world All shells shown on the following plates are from the • study evolution, connectivity and dispersal Queensland Museum Biodiversity Collection. throughout the Indo-Pacific • keep track of invasive and exotic species. Many of the scientists who work at the Museum specialise in taxonomy, the science of describing and naming species. In fact, Queensland Museum scientists -

“Actualización Y Sistematización De Los Equinodermos (Phylum

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA “Actualización y sistematización de los equinodermos (Phylum Echinodermata Klein, 1754) de la Colección Paleontológica de la Facultad de Ingeniería, UNAM”. MATERIAL DIDÁCTICO Que para obtener el título de Ingeniero Geólogo P R E S E N T A Luis Manuel Bautista Mondragón ASESORA DE MATERIAL DIDÁCTICO Dra. Blanca Estela Margarita Buitrón Sánchez Ciudad Universitaria, Cd. Mx., 2018 DEDICATORIAS A mi madre Amanda Mondragón. Por ser el pilar más importante, por sus consejos, sus valores, por la motivación constante que me ha permitido ser una persona de bien, pero más que nada, por su apoyo incondicional sin importar nuestras diferencias de opiniones. A mi mamá Raquel González (QEPD). Por quererme y apoyarme siempre, este logro también se lo debo a ella. A Daniel Guido. Por tu apoyo, dedicación, comprensión y amor. Tus palabras, consejos y enseñanzas me hicieron alcanzar este gran logro y sé que nunca me dejarás caer. A mis maestros. A todos mis maestros de la carrera por sembrar en mi los conocimientos, habilidades y experiencias, en especial a la Dra. Blanca Estela Buitrón Sánchez que siempre me apoyo y creyó en mí, que cuando estaba en momentos difíciles me decía "que no me bajara del caballo", palabras que sembró en mi ser y que están dando frutos. A toda mi familia que de una u otra forma ayudaron y creyeron en mí, a mis amigos en especial a Paola Hernández, Raúl Soria, Xóchitl Contreras, Rafael Villanueva, José Carlos Jiménez, entre otros y también a compañeros que directa o indirectamente son parte de este logro. -

Echinoidea: Clypeasteroida)

Zootaxa 3857 (4): 501–526 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3857.4.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:76021E0C-7542-455B-82F4-C670A3DC8806 Phylogenetic re-evaluation of fossil and extant micro-echinoids with revision of Tridium, Cyamidia, and Lenicyamidia (Echinoidea: Clypeasteroida) RICH MOOI1, ANDREAS KROH2,4 & DINESH K. SRIVASTAVA3 1Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Geology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, California 94118, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Burgring 7, 1010 Vienna, Austria. E-mail: [email protected] 3Centre of Advanced Study in Geology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow 226 007, India. E-mail: [email protected] 4Corresponding author Abstract Tridium kieri Tandon & Srivastava, 1980, a clypeasteroid micro-echinoid from the Middle Eocene of Kachchh, India, has an apical system with just 3 gonopores. This condition is otherwise almost unknown among clypeasteroids, yet the mor- phology of Tridium is very similar to that of extant Fibularia, including members of another relatively poorly known ge- nus from the Indian subcontinent and Western Australia, Cyamidia Lambert & Thiéry, 1914. Re-examination of the type and additional material of T. kieri and Cyamidia paucipora Brunnschweiler, 1962, along with specimens identified as C. nummulitica nummulitica (Duncan & Sladen, 1884), allows for redescription of these forms. For the first time, maps of coronal plate architecture of Tridium and Cyamidia are developed, and SEM images of test surface details of the former are provided. -

CROSS-SHELF TRANSPORT of PLANKTONIC LARVAE of INNER SHELF BENTHIC INVERTEBRATES LAURA ANN BRINK a THESIS Presented to the Depart

CROSS-SHELF TRANSPORT OF PLANKTONIC LARVAE OF INNER SHELF BENTHIC INVERTEBRATES by LAURA ANN BRINK I, A THESIS Presented to the Department ofBiology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master ofScience March 1997 11 "Cross-Shelf Transport of Planktonic Larvae of Inner Shelf Benthic Invertebrates," a thesis prepared by Laura Ann Brink in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Department of Biology. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: the Examining Committee Date Committee in charge: Dr. Alan Shanks, Chair Dr. Steve Rumrill Dr. Lynda Shapiro Accepted by: Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School 111 An Abstract of the Thesis of Laura Ann Brink for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Biology to be taken March 1997 Title: CROSS-SHELF TRANSPORT OF PLANKTONIC LARVAE OF INNER SHELF Approved: -l~P:::::::::~~~~'.1------- Ian Shanks There are two schools of thought on the affect of the physical environment in larval transport and dispersal. One is that larvae act as passive particles, being transported solely by physical means. The other idea is that through behavioral changes, larvae can alter their transport so as to improve their chances of successfully settling. Both cross-shelf and 23 hour vertical sampling of meroplanktonic larvae was conducted to investigate the hypothesis that larvae act as passive particles, being dispersed by the currents. The lengths ofbivalve larvae were also measured to determine if there were ontogenetic differences in the vertical distributions of these larvae. -

First Record of the Irregular Sea Urchin Lovenia Cordiformis (Echinodermata: Spatangoida: Loveniidae) in Colombia C

Muñoz and Londoño-Cruz Marine Biodiversity Records (2016) 9:67 DOI 10.1186/s41200-016-0022-9 RECORD Open Access First record of the irregular sea urchin Lovenia cordiformis (Echinodermata: Spatangoida: Loveniidae) in Colombia C. G. Muñoz1* and E. Londoño-Cruz1,2 Abstract Background: A first record of occurrence of the irregular sea urchin Lovenia cordiformis in the Colombian Pacific is herein reported. Results: We collected one specimen of Lovenia cordiformis at Gorgona Island (Colombia) in a shallow sandy bottom next to a coral reef. Basic morphological data and images of the collected specimen are presented. The specimen now lies at the Echinoderm Collection of the Marine Biology Section at Universidad del Valle (Cali, Colombia; Tag Code UNIVALLE: CRBMeq-UV: 2014–001). Conclusions: This report fills a gap in and completes the distribution of the species along the entire coast of the Panamic Province in the Tropical Eastern Pacific, updating the echinoderm richness for Colombia to 384 species. Keywords: Lovenia cordiformis, Loveniidae, Sea porcupine, Heart urchin, Gorgona Island Background continental shelf of the Pacific coast of Colombia, filling Heart shape-bodied sea urchins also known as sea por- in a gap of its coastal distribution in the Tropical Eastern cupines (family Loveniidae), are irregular echinoids char- Pacific (TEP). acterized by its secondary bilateral symmetry. Unlike most sea urchins, features of the Loveniidae provide dif- Materials and methods ferent anterior-posterior ends, with mouth and anus lo- One Lovenia cordiformis specimen was collected on cated ventrally and distally on an oval-shaped horizontal October 19, 2012 by snorkeling during low tide at ap- plane. -

Taxonomy of Tropical West African Bivalves V. Noetiidae

Bull. Mus. nati. Hist, nat., Paris, 4' sér., 14, 1992, section A, nos 3-4 : 655-691. Taxonomy of Tropical West African Bivalves V. Noetiidae by P. Graham OLIVER and Rudo VON COSEL Abstract. — Five species of Noetiidae are described from tropical West Africa, defined here as between 23° N and 17°S. The Noetiidae are represented by five genera, and four new taxa are introduced : Stenocista n. gen., erected for Area gambiensis Reeve; Sheldonella minutalis n. sp., Striarca lactea scoliosa n. subsp. and Striarca lactea epetrima n. subsp. Striarca lactea shows considerable variation within species. Ecological factors and geographical clines are invoked to explain some of this variation but local genetic isolation could not be excluded. The relationships of the shallow water West African noetiid species are analysed and compared to the faunas of the Mediterranean, Caribbean, Panamic and Indo- Pacific regions. Stenocista is the only genus endemic to West Africa. A general discussion on the relationships of all the shallow water West African Arcoidea is presented. The level of generic endemism is low and there is clear evidence of circumtropical patterns of similarity between species. The greatest affinity is with the Indo-Pacific but this pattern is not consistent between subfamilies. Notably the Anadarinae have greatest similarity to the Panamic faunal province. Résumé. — Description de cinq espèces de Noetiidae d'Afrique occidentale tropicale, ici définie entre 23° N et 17° S. Les Noetiidae sont représentés par cinq genres. Quatre taxa nouveaux sont décrits : Stenocista n. gen. (espèce-type Area gambiensis Reeve) ; Sheldonella minutalis n. sp., Striarca lactea scoliosa n. -

The Marine Mollusca of Suriname (Dutch Guiana) Holocene and Recent

THE MARINE MOLLUSCA OF SURINAME (DUTCH GUIANA) HOLOCENE AND RECENT Part II. BIVALVIA AND SCAPHOPODA by G. O. VAN REGTEREN ALTENA Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden "The student must know something of syste- matic work. This is populary supposed to be a dry-as-dust branch of zoology. In fact, the systematist may be called the dustman of biol- ogy, for he performs a laborious and frequently thankless task for his fellows, and yet it is one which is essential for their well-being and progress". Maud D. Haviland in: Forest, steppe and tundra, 1926. CONTENTS Ι. Introduction, systematic survey and page references 3 2. Bivalvia and Scaphopoda 7 3. References 86 4. List of corrections of Part I 93 5. Plates 94 6. Addendum 100 1. INTRODUCTION, SYSTEMATIC SURVEY AND PAGE REFERENCES In the first part of this work, published in 1969, I gave a general intro- duction to the Suriname marine Mollusca ; in this second part the Bivalvia and Scaphopoda are treated. The system (and frequently also the nomen- clature) of the Bivalvia are those employed in the "Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, (N) Mollusca 6, Part I, Bivalvia, Volume 1 and 2". These volumes were issued in 1969 and contain the most modern system of the Bivalvia. For the Scaphopoda the system of Thiele (1935) is used. Since I published in 1968 a preliminary list of the marine Bivalvia of Suriname, several additions and changes have been made. I am indebted to Messrs. D. J. Green, R. H. Hill and P. G. E. F. Augustinus for having provided many new coastal records for several species. -

The Panamic Biota: Some Observations Prior to a Sea-Level Canal

Bulletin of the Biological Society of Washington No. 2 THE PANAMIC BIOTA: SOME OBSERVATIONS PRIOR TO A SEA-LEVEL CANAL A Symposium Sponsored by The Biological Society of Washington The Conservation Foundation The National Museum of Natural History The Smithsonian Institution MEREDITH L. JONES, Editor September 28, 1972 CONTENTS Foreword The Editor - - - - - - - - - - Introduction Meredith L. Jones ____________ vi A Tribute to Waldo Lasalle Schmitt George A. Llano 1 Background for a New, Sea-Level, Panama Canal David Challinor - - - - - - - - - - - Observations on the Ecology of the Caribbean and Pacific Coasts of Panama - - - - Peter W. Glynn _ 13 Physical Characteristics of the Proposed Sea-Level Isthmian Canal John P. Sheffey - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 31 Exchange of Water through the Proposed Sea-Level Canal at Panama Donald R. F. Harleman - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 41 Biological Results of the University of Miami Deep-Sea Expeditions. 93. Comments Concerning the University of Miami's Marine Biological Survey Related to the Panamanian Sea-Level Canal Gilbert L. Voss - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 49 Museums as Environmental Data Banks: Curatorial Problems Posed by an Extensive Biological Survey Richard S. Cowan - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 59 A Review of the Marine Plants of Panama Sylvia A. Earle - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 69 Ecology and Species Diversity of -

Invertebrate Predators and Grazers

9 Invertebrate Predators and Grazers ROBERT C. CARPENTER Department of Biology California State University Northridge, California 91330 Coral reefs are among the most productive and diverse biological communities on earth. Some of the diversity of coral reefs is associated with the invertebrate organisms that are the primary builders of reefs, the scleractinian corals. While sessile invertebrates, such as stony corals, soft corals, gorgonians, anemones, and sponges, and algae are the dominant occupiers of primary space in coral reef communities, their relative abundances are often determined by the activities of mobile, invertebrate and vertebrate predators and grazers. Hixon (Chapter X) has reviewed the direct effects of fishes on coral reef community structure and function and Glynn (1990) has provided an excellent review of the feeding ecology of many coral reef consumers. My intent here is to review the different types of mobile invertebrate predators and grazers on coral reefs, concentrating on those that have disproportionate effects on coral reef communities and are intimately involved with the life and death of coral reefs. The sheer number and diversity of mobile invertebrates associated with coral reefs is daunting with species from several major phyla including the Annelida, Arthropoda, Mollusca, and Echinodermata. Numerous species of minor phyla are also represented in reef communities, but their abundance and importance have not been well-studied. As a result, our understanding of the effects of predation and grazing by invertebrates in coral reef environments is based on studies of a few representatives from the major groups of mobile invertebrates. Predators may be generalists or specialists in choosing their prey and this may determine the effects of their feeding on community-level patterns of prey abundance (Paine, 1966). -

Gastropods Diversity in Thondaimanaru Lagoon (Class: Gastropoda), Northern Province, Sri Lanka

Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 2021, 9, 21-30 https://www.scirp.org/journal/gep ISSN Online: 2327-4344 ISSN Print: 2327-4336 Gastropods Diversity in Thondaimanaru Lagoon (Class: Gastropoda), Northern Province, Sri Lanka Amarasinghe Arachchige Tiruni Nilundika Amarasinghe, Thampoe Eswaramohan, Raji Gnaneswaran Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Jaffna, Jaffna, Sri Lanka How to cite this paper: Amarasinghe, A. Abstract A. T. N., Eswaramohan, T., & Gnaneswa- ran, R. (2021). Gastropods Diversity in Thondaimanaru lagoon (TL) is one of the three lagoons in the Jaffna Penin- Thondaimanaru Lagoon (Class: Gastropo- sula, Sri Lanka. TL (N-9.819584, E-80.134086), which is 74.5 Km2. Fringing da), Northern Province, Sri Lanka. Journal these lagoons are mangroves, large tidal flats and salt marshes. The present of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 9, 21-30. study is carried out to assess the diversity of gastropods in the northern part https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2021.93002 of the TL. The sampling of gastropods was performed by using quadrat me- thod from July 2015 to June 2016. Different sites were selected and rainfall Received: January 25, 2020 data, water temperature, salinity of the water and GPS values were collected. Accepted: March 9, 2021 Published: March 12, 2021 Collected gastropod shells were classified using standard taxonomic keys and their morphological as well as morphometrical characteristics were analyzed. Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and A total of 23 individual gastropods were identified from the lagoon which Scientific Research Publishing Inc. belongs to 21 genera of 15 families among them 11 gastropods were identified This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International up to species level. -

CONE SHELLS - CONIDAE MNHN Koumac 2018

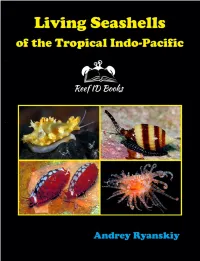

Living Seashells of the Tropical Indo-Pacific Photographic guide with 1500+ species covered Andrey Ryanskiy INTRODUCTION, COPYRIGHT, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION Seashell or sea shells are the hard exoskeleton of mollusks such as snails, clams, chitons. For most people, acquaintance with mollusks began with empty shells. These shells often delight the eye with a variety of shapes and colors. Conchology studies the mollusk shells and this science dates back to the 17th century. However, modern science - malacology is the study of mollusks as whole organisms. Today more and more people are interacting with ocean - divers, snorkelers, beach goers - all of them often find in the seas not empty shells, but live mollusks - living shells, whose appearance is significantly different from museum specimens. This book serves as a tool for identifying such animals. The book covers the region from the Red Sea to Hawaii, Marshall Islands and Guam. Inside the book: • Photographs of 1500+ species, including one hundred cowries (Cypraeidae) and more than one hundred twenty allied cowries (Ovulidae) of the region; • Live photo of hundreds of species have never before appeared in field guides or popular books; • Convenient pictorial guide at the beginning and index at the end of the book ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The significant part of photographs in this book were made by Jeanette Johnson and Scott Johnson during the decades of diving and exploring the beautiful reefs of Indo-Pacific from Indonesia and Philippines to Hawaii and Solomons. They provided to readers not only the great photos but also in-depth knowledge of the fascinating world of living seashells. Sincere thanks to Philippe Bouchet, National Museum of Natural History (Paris), for inviting the author to participate in the La Planete Revisitee expedition program and permission to use some of the NMNH photos.