Nightmare Magazine, Issue 55 (April 2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Hugo Nominees

Top 2003 Hugo Award Nominations for Each Category There were 738 total valid nominating forms submitted Nominees not on the final ballot were not validated or checked for errors Nominations for Best Novel 621 nominating forms, 219 nominees 97 Hominids by Robert J. Sawyer (Tor) 91 The Scar by China Mieville (Macmillan; Del Rey) 88 The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson (Bantam) 72 Bones of the Earth by Michael Swanwick (Eos) 69 Kiln People by David Brin (Tor) — final ballot complete — 56 Dance for the Ivory Madonna by Don Sakers (Speed of C) 55 Ruled Britannia by Harry Turtledove NAL 43 Night Watch by Terry Pratchett (Doubleday UK; HarperCollins) 40 Diplomatic Immunity by Lois McMaster Bujold (Baen) 36 Redemption Ark by Alastair Reynolds (Gollancz; Ace) 35 The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde (Viking) 35 Permanence by Karl Schroeder (Tor) 34 Coyote by Allen Steele (Ace) 32 Chindi by Jack McDevitt (Ace) 32 Light by M. John Harrison (Gollancz) 32 Probability Space by Nancy Kress (Tor) Nominations for Best Novella 374 nominating forms, 65 nominees 85 Coraline by Neil Gaiman (HarperCollins) 48 “In Spirit” by Pat Forde (Analog 9/02) 47 “Bronte’s Egg” by Richard Chwedyk (F&SF 08/02) 45 “Breathmoss” by Ian R. MacLeod (Asimov’s 5/02) 41 A Year in the Linear City by Paul Di Filippo (PS Publishing) 41 “The Political Officer” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 04/02) — final ballot complete — 40 “The Potter of Bones” by Eleanor Arnason (Asimov’s 9/02) 34 “Veritas” by Robert Reed (Asimov’s 7/02) 32 “Router” by Charles Stross (Asimov’s 9/02) 31 The Human Front by Ken MacLeod (PS Publishing) 30 “Stories for Men” by John Kessel (Asimov’s 10-11/02) 30 “Unseen Demons” by Adam-Troy Castro (Analog 8/02) 29 Turquoise Days by Alastair Reynolds (Golden Gryphon) 22 “A Democracy of Trolls” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 10-11/02) 22 “Jury Service” by Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow (Sci Fiction 12/03/02) 22 “Paradises Lost” by Ursula K. -

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 33 (June 2015)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 33, June 2015 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, June 2015 FICTION The Cellar Dweller Maria Dahvana Headley The Changeling Sarah Langan Snow Dale Bailey The Music of the Dark Time Chet Williamson NONFICTION The H Word: Why Do We Read Horror? Mike Davis Artist Gallery Okan Bülbül Artist Spotlight: Okan Bülbül Marina J. Lostetter Interview: Lucy A. Snyder Lisa Morton AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Maria Dahvana Headley Sarah Langan Dale Bailey Chet Williamson MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions & Ebooks About the Editor © 2015 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Okan Bülbül Ebook Design by John Joseph Adams www.nightmare-magazine.com FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, June 2015 John Joseph Adams Welcome to issue thirty-three of Nightmare! ICYMI last month, the final installment of The Apocalypse Triptych — the apocalyptic anthology series I co-edited with Hugh Howey — is now available. The new volume, The End Has Come, focuses on life after the apocalypse. The first two volumes, The End is Nigh (about life before the apocalypse) and The End is Now (about life during the apocalypse) are also available. If you’d like a preview of the anthology, you’re in luck: You can read Annie Bellet’s The End Has Come story in the May issue of Lightspeed. Pop over there to read it, or visit johnjosephadams.com/apocalypse-triptych for more information about the book. • • • • In other news, this month also marks the publication of our sister- magazine Lightspeed’s big special anniversary issue, Queers Destroy Science Fiction! We’ve brought together a team of terrific queer creators and editors, led by guest editor and bestselling author, Seanan McGuire. -

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

23 YEARS EXPLORING SCIENCE FICTION ^ GOLDFINGER s Jjr . Golden Girl: Tests RicklBerfnanJponders Er_ her mettle MimilMif-lM ]puTtism!i?i ff?™ § m I rifbrm The Mail Service Hold Mail Authorization Please stop mail for: Name Date to Stop Mail Address A. B. Please resume normal Please stop mail until I return. [~J I | undelivered delivery, and deliver all held I will pick up all here. mail. mail, on the date written Date to Resume Delivery Customer Signature Official Use Only Date Received Lot Number Clerk Delivery Route Number Carrier If option A is selected please fill out below: Date to Resume Delivery of Mail Note to Carrier: All undelivered mail has been picked up. Official Signature Only COMPLIMENTS OF THE STAR OCEAN GAME DEVEL0PER5. YOU'RE GOING TO BE AWHILE. bad there's Too no "indefinite date" box to check an impact on the course of the game. on those post office forms. Since you have no Even your emotions determine the fate of your idea when you'll be returning. Everything you do in this journey. You may choose to be romantically linked with game will have an impact on the way the journey ends. another character, or you may choose to remain friends. If it ever does. But no matter what, it will affect your path. And more You start on a quest that begins at the edge of the seriously, if a friend dies in battle, you'll feel incredible universe. And ends -well, that's entirely up to you. Every rage that will cause you to fight with even more furious single person you _ combat moves. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

Metahorror #1992

MetaHorror #1992 MetaHorror #Dell, 1992 #9780440208990 #Dennis Etchison #377 pages #1992 Never-before-published, complete original works by 20 of today's unrivaled masters, including Peter Straub, David Morrell, Whitley Strieber, Ramsey Campbell, Thomas Tessier, Joyce Carol Oates, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, and William F. Nolan. The Abyss line is . remarkable. I hope to be looking into the Abyss for a long time to come.-- Stephen King. DOWNLOAD i s. gd/l j l GhE www.bit.ly/2DXqbU6 Collects tales of madmen, monsters, and the macabre by authors including Peter Straub, Joyce Carol Oates, Robert Devereaux, Susan Fry, and Ramsey Campbell. #The Museum of Horrors #Apr 30, 2003 #Dennis Etchison ISBN:1892058030 #The death artist #Dennis Etchison #. #Aug 1, 2000 Santa Claus and his stepdaughter Wendy strive to remake the world in compassion and generosity, preventing one child's fated suicide by winning over his worst tormentors, then. #Aug 1, 2008 #Santa Claus Conquers the Homophobes #Robert Devereaux #ISBN:1601455380 STANFORD:36105015188431 #Dun & Bradstreet, Ltd. Directories and Advertising Division #1984 #. #Australasia and Far East #Who Owns Whom, https://ozynepowic.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/maba.pdf Juvenile Fiction #The Woman in Black #2002 #Susan Hill, John Lawrence #ISBN:1567921892 #A Ghost Story #1986 Set on the obligatory English moor, on an isolated cause-way, the story stars an up-and-coming young solicitor who sets out to settle the estate of Mrs. Drablow. Routine. #https://is.gd/lDsWvO #Javier A. Martinez See also: Bram Stoker Award;I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream;The Whim- per of Whipped Dogs; World Fantasy Award. -

Lucius Shepard, He Was a Friend of Mine

EDITORIAL Sheila Williams LUCIUS SHEPARD, HE WAS A FRIEND OF MINE “Not Long after the Christlight of the world’s first morning faded, when birds still flew to heaven and back, and even the wickedest things shone like saints, so pure was their portion of evil, there was a village by the name of Hangtown that clung to the back of the dragon Griaule.” These are the evocative opening words to Lucius Shepard’s “The Scalehunter’s Beautiful Daughter,” a novella that won the 1988 Lo- cus Poll and came in second in our own Readers’ Award poll. In all the years that I’ve worked at Asimov’s, this is, perhaps, the loveliest beginning to a story I’ve ever en- countered. My own friendship with Lucius began about thirty years ago when we published “A Traveler’s Tale” in our July 1984 issue. I first met him in our office in the spring of 1984. He was moving to New York from Florida, and for a while I got to see him in person fairly often. After a couple of sublets in Manhattan, he moved to Staten Island and visits became rare. But, like many of his friendships, our relationship continued to grow and deepen over the telephone. In those days before Amazon, he was a bit iso- lated in that outer borough, so calls would come in asking for favors—can you mail me a ream of computer paper? How about a copy of the I Ching? I need its advice for a story I’m working on. -

Exhibition Hall

exhibition hall 15 the weird west exhibition hall - november 2010 chris garcia - editor, ariane wolfe - fashion editor james bacon - london bureau chief, ric flair - whooooooooooo! contact can be made at [email protected] Well, October was one of the stronger months for Steampunk in the public eye. No conventions in October, which is rare these days, but there was the Steampunk Fortnight on Tor.com. They had some seriously good stuff, including writing from Diana Vick, who also appears in these pages, and myself! There was a great piece from Nisi Shawl that mentioned the amazing panel that she, Liz Gorinsky, Michael Swanwick and Ann VanderMeer were on at World Fantasy last year. Jaymee Goh had a piece on Commodification and Post-Modernism that was well-written, though slightly troubling to me. Stephen Hunt’s Steampunk Timeline was good stuff, and the omnipresent GD Falksen (who has never written for us!) had a couple of good piece. Me? I wrote an article about how Tomorrowland was the signpost for the rise of Steampunk. You can read it at http://www.tor.com/blogs/2010/10/goodbye-tomorrow- hello-yesterday. The second piece is all about an amusement park called Gaslight in New Orleans. I’ll let you decide about that one - http://www.tor.com/blogs/2010/10/gaslight- amusement. The final one all about The Cleveland Steamers. This much attention is a good thing for Steampunk, especially from a site like Tor.com, a gateway for a lot of SF readers who aren’t necessarily a part of fandom. -

2017 Capps Stephanie Carol

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE WHAT YOU READ AND WHAT YOU BELIEVE: GENRE EXPOSURE AND BELIEFS ABOUT RELATIONSHIPS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE BY STEPHANIE CAROL CAPPS Norman, Oklahoma 2017 WHAT YOU READ AND WHAT YOU BELIEVE: GENRE EXPOSURE AND BELIEFS ABOUT RELATIONSHIPS A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Jennifer Barnes, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Lara Mayeux ______________________________ Dr. Mauricio Carvallo © Copyright by STEPHANIE CAROL CAPPS 2017 All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents List of Tables ……………………………………………………………………………v List of Figures …………………………...……………………………………………..vi Abstract ………………………………………………………………………...……...vii Introduction …………………………...……………………………………………….. 1 Study 1 ……………………………………...………………………………………….. 9 Methods …………………………...……...………………………………………… 9 Participants ………………………………...……………………………………….. 9 Materials ………………………………………………………………………...… 10 Study 1 Results ……………………………………………………………………….. 12 Study 1 Discussion …………………………………………………………………… 15 Study 2 ………………………………………………………………………………... 16 Methods …………………………………………………………………………... 16 Participants ……………………………………………………………………….. 16 Materials ………………………………………………………………………….. 16 Procedure …………………………………………………………………………. 18 Study 2 Results …...…………………………………………………………………... 18 Study 2 Discussion .…………………………………………………………………... 20 General Discussion. …………………………………………………………………... 21 References ………………………………...…………………………………………. -

Bulletin 7/13C

Southern Fandom Confederation Contents SFC Handbooks Off the Wall . .1 This amazing 196 page tome of Southern Fannish lore, edited Treasurer’s Report . .3 by T.K.F. Weisskopf, is now available to all comers for $5, plus Contributors . .3 a $2 handling and shipping charge if we have to mail it. The Nebula Award Winners . .3 Handbook is also available online, thanks to the efforts of Sam Hugo Nominees . .4 Smith, at http://www.smithuel.net/sfchb Convention Reports . .6 T-Shirts Convention Listing . .8 Fanzine Listings . .10 Size S to 3X LoCs . .12 Price $10 {{Reduced!}} Plus $3 shipping and handling fee if we have to mail it. Policies Art Credits The Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin Vol. 7, No. 13, Cover, Page 1 . .Teddy Harvia June 2002, is the official publication of the Southern Fandom This page, Page 2,3,6,7,12,14,18 . .Trinlay Khadro Confederation (SFC), a not-for-profit literary organization and Page 5, 17 . .Scott Thomas . information clearinghouse dedicated to the service of Southern Page 19 . .Sheryl Birkhead Science Fiction and Fantasy Fandom. The SFC Bulletin is edit- ed by Julie Wall and is published at least three times per year. Addresses of Officers Membership in the SFC is $15 annually, running from DeepSouthCon to DeepSouthCon. A club or convention mem- Physical Mail: bership is $75 annually. Donations are welcome. All checks President Julie Wall, should be made payable to the Southern Fandom 470 Ridge Road, Birmingham, AL 35206 Confederation. Vice-President Bill Francis, Permission is granted to reprint all articles, lists, and fly- PO Box 1271, Brunswick, GA 31521 ers so long as the author and the SFCB are credited. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

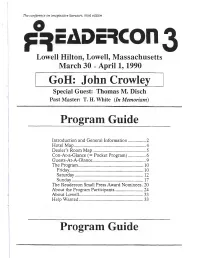

John Crowley Program Guide Program Guide

The conference on imaginative literature, third edition pfcADcTCOn 3 Lowell Hilton, Lowell, Massachusetts March 30 - April 1,1990 GoH: John Crowley Special Guest: Thomas M. Disch Past Master: T. H. White (In Memoriam) Program Guide Introduction and General Information...............2 Hotel Map........................................................... 4 Dealer’s Room Map............................................ 5 Con-At-a-Glance (= Pocket Program)...............6 Guests-At-A-Glance............................................ 9 The Program...................................................... 10 Friday............................................................. 10 Saturday.........................................................12 Sunday........................................................... 17 The Readercon Small Press Award Nominees. 20 About the Program Participants........................24 About Lowell.....................................................33 Help Wanted.....................................................33 Program Guide Page 2 Readercon 3 Introduction Volunteer! Welcome (or welcome back) to Readercon! Like the sf conventions that inspired us, This year, we’ve separated out everything you Readercon is entirely volunteer-run. We need really need to get around into this Program (our hordes of people to help man Registration and Guest material and other essays are now in a Information, keep an eye on the programming, separate Souvenir Book). The fact that this staff the Hospitality Suite, and to do about a Program is bigger than the combined Program I million more things. If interested, ask any Souvenir Book of our last Readercon is an committee member (black or blue ribbon); they’ll indication of how much our programming has point you in the direction of David Walrath, our expanded this time out. We hope you find this Volunteer Coordinator. It’s fun, and, if you work division of information helpful (try to check out enough hours, you earn a free Readercon t-shirt! the Souvenir Book while you’re at it, too).