The Toyota Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extension of the Lean 5S Methodology to 6S with an Additional Layer to Ensure Occupational Safety and Health Levels

sustainability Article Extension of the Lean 5S Methodology to 6S with An Additional Layer to Ensure Occupational Safety and Health Levels Mariano Jiménez 1,2 , Luis Romero 2,* , Jon Fernández 2, María del Mar Espinosa 2 and Manuel Domínguez 2 1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Technical School of Engineering—ICAI, Comillas Pontifical University, 25, 28015 Madrid, Spain 2 Design Engineering Area, Industrial Engineering School, National Distance Education University (UNED), 38, 28015 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 June 2019; Accepted: 11 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: This paper proposes an expansion of the Lean 5S methodology, which includes the concept of Safety–Security as 6S. Implementation was done by a standardized process tested in a pilot area that is part of the Integrated Industrial Manufacturing System Laboratory at the Higher Technical School of Engineering (ICAI). The additional 6S phase (Safety-Security) thoroughly reviews all areas of an industrial plant by analyzing the risks at each workstation, which let employees be fitted out with protection resources depending on each of their personal characteristics and to guarantee the safety of the workstation by strictly complying with occupational safety and health and machinery use standards, which must hold a CE certificate of compliance. The main objective was to increase the scope of 5S methodology to respond to the occupational safety and health needs for machines required in optimizing production processes. It is important to remember that companies must guarantee that their employees use personal protection equipment (PPE) at their work posts or stations that protect them properly from risks to their health and safety and that cannot be prevented or sufficiently limited by using collective means of protection or by adopting work organization measures. -

Waste Measurement Techniques for Lean Companies

WASTE MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES FOR LEAN COMPANIES Maciej Pieńkowski PhD student Wrocław University of Economics Komandorska 118/120, Wrocław, Poland [email protected] A B S T R A C T K E Y W O R D S Waste measurement, The paper is dedicated to answer the problem of lean manufacturing, lean metrics measuring waste in companies, which are implementing Lean Manufacturing concept. Lack of complex identification, quantification an visualization of A R T I C L E I N F O waste significantly impedes Lean transformation Received 07 June 2014 Accepted 17 June 2014 efforts. This problem can be solved by a careful Available online1 December 2014 investigation of Muda, Muri and Mura, which represent the essence of waste in the Toyota Production System. Measuring them facilitates complete and permanent elimination of waste in processes. The paper introduces a suggestion of methodology, which should enable company to quantify and visualize waste at a shop floor level. 1. Introduction Lean Management, originated from the Toyota Production System, is nowadays one of the most dominating management philosophies, both in industrial and service environment. One of the reasons for such a success is its simplicity. The whole concept is based on a common sense idea of so called “waste”. Removing it is the very essence of Lean Management. Despite seemingly simple principles, eliminating waste is not an easy task. Many companies, even those with many years of Lean experience, still struggle to clear the waste out of their processes. It turns out, that the most difficult part is not removing waste itself, but identifying and highlighting it, which should precede the process of elimination. -

The Toyotatoyota Wayway (The Company That Invented Lean Production)

TheThe ToyotaToyota WayWay (The Company that invented Lean Production) 1414 ManagementManagement PrinciplesPrinciples fromfrom thethe World’sWorld’s GreatestGreatest Manufacturer Manufacturer By: Jeffrey K. Liker (Paperback,330p,ISBN 0-07-058747-7,Rs. 250) (Tata McGraw-Hill) Why to read this book ? •• You’ll learn how Toyota creates an ideal environment for implementing Lean techniques & tools by :: -Fostering an atmosphere of continuous improvement and learning -Satisfying customers (and eliminating waste at the same time) -Getting quality right the first time -Grooming leaders from within rather than recruiting them from the outside -Teaching all employees to become problem solver -Growing together with suppliers and partners for mutual benefits About Toyota •• Market capitalization over $ 105 billion; 2,40,000 employees •• 3rd Largest auto manufacturer in the world; behind GM & Ford •• Global Vehicle sale of over 6 million per year in 170 countries •• Big Brands like Corolla, Camry, Lexus •• Annual Profit margin: 8.3 times higher than industry average Contents… •• DevelopmentDevelopment ofof ToyotaToyota ProductionProduction SystemSystem “TPS”“TPS” (5-9)(5-9) •• FundamentalsFundamentals ofof TPSTPS (10-15)(10-15) •• TheThe ToyotaToyota PrinciplesPrinciples (16-19)(16-19) •• WhatWhat cancan bebe learntlearnt fromfrom ToyotaToyota (20-28)(20-28) •• HowHow toto adoptadopt TPSTPS (29-32)(29-32) DevelopmentDevelopment ofof ToyotaToyota ProductionProduction SystemSystem (TPS)(TPS) •• Toyota customer requirement was in small lots & different verities unlike Ford & GM using ‘mass production’ concepts •• These requirement is to be met with same assembly line •• Toyota was having cash crunch and there was no stable supply chain •• Toyota studied that ‘mass production’ concepts cannot be feasible in Japan. Ford & GM were facing many issues due to same. -

Review on Implementation 5S System in Educational

REVIEW ON IMPLEMENTATION 5S SYSTEM IN EDUCATIONAL LABORATORIES L.Ramanathan1, S.Jeevanantham2, D.Logu3, V.Purushothaman4 1Assistant Professor, 2,3,4UG Scholar, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Sri Ramakrishna Engineering College, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India ABSTRACT educational laboratory. Using 5S, the The purpose of this review paper is to laboratory was expected to improve in the study the significance of imple menting areas of working environment, safety, s ome of principles of the 5s and kaizen to reduction of equipment search time, and enhance the productivity of increase deficiency. manufacturing organizations to become Educational laboratories that provide more efficient and more productive. 5s is students with experiential learning that a basic tool of lean manufacturing systems create knowledge through insights gained by which is used for sorting, organizing and practical experience has become an integral systemizing the necessary things for job part of undergraduate STEM education place enhance ment. The research findings (Reck, 2016). Universities and technical from the literature review shows that the colleges aim to close the gap between theory industries have developed the necessity of and industrial practice using educational imple menting the 5s in the job shop and laboratories. These laboratories have according to them, implementing the 5s is technical resources and comparable relatively possible. Moreover, the functional characteristics with industrial educational institute’s labs has been a facilities (Jimenez et. al., 2015). They platform whe re 5s can also be prepare students with the skills required to imple mented. It is also to make the work in a professional environment (Gibbins student teachers become aware of & Perkin, 2013). -

Toyota Production System Toyota Production System

SNS COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AN AUTONOMOUS INSTITUTION Kurumbapalayam (Po), Coimbatore – 641 107 Accredited by NBA – AICTE and Accredited by NAAC – UGC with ‘A’ Grade Approved by AICTE, New Delhi & Affiliated to Anna University, Chennai TOYOTA PRODUCTION SYSTEM 1 www.a2zmba.com Vision Contribute to Indian industry and economy through technology transfer, human resource development and vehicles that meet global standards at competitive price. Contribute to the well-being and stability of team members. Contribute to the overall growth for our business associates and the automobile industry. 2 www.a2zmba.com Mission Our mission is to design, manufacture and market automobiles in India and overseas while maintaining the high quality that meets global Toyota quality standards, to offer superior value and excellent after-sales service. We are dedicated to providing the highest possible level of value to customers, team members, communities and investors in India. www.a2zmba.com 3 7 Principles of Toyota Production System Reduced setup time Small-lot production Employee Involvement and Empowerment Quality at the source Equipment maintenance Pull Production Supplier involvement www.a2zmba.com 4 Production System www.a2zmba.com 5 JUST-IN-TIME Produced according to what needed, when needed and how much needed. Strategy to improve return on investment by reducing inventory and associated cost. The process is driven by Kanban concept. www.a2zmba.com 6 KANBAN CONCEPT Meaning- Sign, Index Card It is the most important Japanese concept opted by Toyota. Kanban systems combined with unique scheduling tools, dramatically reduces inventory levels. Enhances supplier/customer relationships and improves the accuracy of manufacturing schedules. A signal is sent to produce and deliver a new shipment when material is consumed. -

The Application of Lean in Healthcare

The Application of Lean in Healthcare Exploratory Paper Erik Liu, MBA, FACMPE August 01, 2018 This paper is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Fellowship in the American College of Medical Practice Executives Abstract The current healthcare environment poses many challenges to medical group practice managers. Aside from their daily tasks of managing operational issues in their medical practices, healthcare administrators must deal with the burgeoning issues of physician burnout, attracting and keeping talented staff, taking charge of the practice’s financial stewardship and ensuring the delivery of quality health care. Healthcare managers are increasingly asked to do more with less. Can Lean management systems help practice managers thrive, not only survive, in the current dynamic healthcare environment? This exploratory paper will attempt to answer this question and explore how practice managers can improve patient and employee satisfaction, improve healthcare quality and safety, and lower operating costs by consistently practicing Lean principles aimed at creating value and removing waste, surfacing and solving problems, and engaging and empowering employees in continuous improvement. Keywords: Lean, Toyota Production System, TPS, Continuous Process Improvement, Kaizen, Problem Solving, Coaching, Standardization, Patient Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, 5S, Andon, Kanban, Value Stream Map, Flow, A3 Report, Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act 1 Introduction The current healthcare environment poses many challenges to medical group practice managers. Government mandates concerning the meaningful use of Electronic Health Records (EHR) have created mountains of administrative tasks for physicians and managers. Reimbursement trends are changing from “pay for volume” to “pay for value”. Big insurance payors are merging and dictating how medicine should be practiced. -

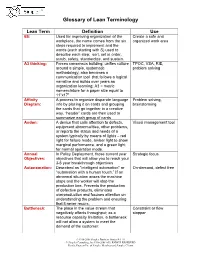

Glossary of Lean Terminology

Glossary of Lean Terminology Lean Term Definition Use 6S: Used for improving organization of the Create a safe and workplace, the name comes from the six organized work area steps required to implement and the words (each starting with S) used to describe each step: sort, set in order, scrub, safety, standardize, and sustain. A3 thinking: Forces consensus building; unifies culture TPOC, VSA, RIE, around a simple, systematic problem solving methodology; also becomes a communication tool that follows a logical narrative and builds over years as organization learning; A3 = metric nomenclature for a paper size equal to 11”x17” Affinity A process to organize disparate language Problem solving, Diagram: info by placing it on cards and grouping brainstorming the cards that go together in a creative way. “header” cards are then used to summarize each group of cards Andon: A device that calls attention to defects, Visual management tool equipment abnormalities, other problems, or reports the status and needs of a system typically by means of lights – red light for failure mode, amber light to show marginal performance, and a green light for normal operation mode. Annual In Policy Deployment, those current year Strategic focus Objectives: objectives that will allow you to reach your 3-5 year breakthrough objectives Autonomation: Described as "intelligent automation" or On-demand, defect free "automation with a human touch.” If an abnormal situation arises the machine stops and the worker will stop the production line. Prevents the production of defective products, eliminates overproduction and focuses attention on understanding the problem and ensuring that it never recurs. -

Lean Manufacturing Techniques for Textile Industry Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017

Lean Manufacturing Techniques For Textile Industry Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017 First published (2017) Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ILO Cataloging in Publication Data/ Lean Manufacturing Techniques for Textile Industry ILO Decent Work Team for North Africa and Country Office for Egypt and Eritrea- Cairo: ILO, 2017. ISBN: 978-92-2-130764-8 (print), 978-92-2-130765-5 (web pdf) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. -

Using PDCA Cycle to Improve the Process of Supplying Cooling Hydrogen for a Combined Cycle Generator at Rabigh Power Plant

Using PDCA Cycle to Improve the process of Supplying Cooling Hydrogen for a Combined Cycle Generator at Rabigh Power Plant Engineer, Waleed Basheer Alsaadi Saudi Electricity Company, Generation Sector, Rabigh Power Plant, Engineering Department, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Prof, Hani Alamri Faculty of Economics & Administration, King Abdul-Aziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Organizations seek to improve their performance by reducing costs and increasing profits to stay in the market and increase competitiveness. Optimal allocation of available resources helps organizations make optimal decisions in customization, minimizes costs and improves performance. This project aims to utilized Kaizen continuous improvement method within the power generation industry. Rabigh Power Plant, as many other generation stations, has ongoing effort to improve daily work activities. The project highlights the experience of using continuous improvement methodology to incrementally increase plant performance, achieve economic savings, and maintain the continuity of electricity flow. The study applied Kaizen methodology to improve the procedure of supplying hydrogen cooling gas to the third combined cycle‟s (CC3) generator at the fourth stage of Rabigh Power Plant. The study recommends to re-engineering the existing system to utilize stage one‟s hydrogen generation plant. The finding shows that re- engineering the system will improve the process cycle by around 98% and reduce the number of tasks by 86%. Keyword: Kaizen; PDCA Cycle; Total Quality; Continuous Improvement Process (CIP), Saudi Arabia; Power Plant; Hydrogen Cooling System; Resources Optimal allocation. ملخص البحث : حسؼً انمىظماث إنً ححسيه أدائها مه خﻻل خفض انخكانيف وصيادة اﻷسباح نهبماء في انسىق وصيادة انمذسة انخىافسيت. -

Page 1 of 8 Process Improvement Concepts and Terminology

Process Improvement Concepts and Terminology (A Guide to the Jargon) Disclaimer: Some statements/definitions are broad generalities intended as an initial introduction to Lean and Six Sigma concepts. (Not in alphabetical order) Methodologies and Related Concepts Lean – Process improvement methodology focused on reducing waste in a system. It is based heavily on the teachings of W. Edwards Deming and the Toyota Production System. The term Lean is derived from the idea that the approach reduces “wastes” that contribute to inefficient processes and poor outcomes. It does NOT refer to the idea that it is a way to cut staff as in the management adage: “lean and mean.” Mura – Japanese term that means “waste.” Key concept in Lean, which focuses on the reduction of “waste.” Muda – Japanese term that means “unevenness.” Workaround – Temporary fix to a system or process breakdown – a reaction to an immediate problem. In some cases, may not work well. Equivalent to “Duct tape on a split on a car radiator hose.” Not a permanent solution. Sometimes the result of procedures created without input from those involved in the process. A workaround does nothing to improve the situation in the future. PDCA/PDSA – Plan, Do, Check or Study, Act – A change process originally developed by Walter Shewhart (PDCA) and later revised by W. Edwards Deming (PDSA). It is sometimes referred to as the Deming wheel. It is intended to be used in multiple, successive cycles. © 2015 PCPI. All rights reserved. Page 1 of 8 Process Improvement Terminology (Jargon) Handout Error-proofing (“poka yoke” Japanese term) – the practice of making a process error proof, or make errors more apparent. -

Lean Manufacturing

8 Lean manufacturing Lean manufacturing, lean enterprise, or lean production, often simply, "Lean", is a production practice that considers the expenditure of resources for any goal other than the creation of value for the end customer to be wasteful, and thus a target for elimination. Working from the perspective of the customer who consumes a product or service, "value" is defined as any action or process that a customer would be willing to pay for. Essentially, lean is centered on preserving value with less work. Lean manufacturing is a management philosophy derived mostly from the Toyota Production System (TPS) (hence the term Toyotism is also prevalent) and identified as "Lean" only in the 1990s. TPS is renowned for its focus on reduction of the original Toyota seven wastes to improve overall customer value, but there are varying perspectives on how this is best achieved. The steady growth of Toyota, from a small company to the world's largest automaker, has focused attention on how it has achieved this success. 8.1 Overview Lean principles are derived from the Japanese manufacturing industry. The term was first coined by John Krafcik in his 1988 article, "Triumph of the Lean Production System," based on his master's thesis at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Krafcik had been a quality engineer in the Toyota-GM NUMMI joint venture in California before coming to MIT for MBA studies. Krafcik's research was continued by the International Motor Vehicle Program (IMVP) at MIT, which produced the international best-seller book co-authored by Jim Womack, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos called The Machine That Changed the World.] A complete historical account of the IMVP and how the term "lean" was coined is given by Holweg (2007). -

Apply Lean Thinking in Project Management

Chi Pham Ngoc Lan Apply Lean Thinking in Project Management Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Engineering Media Engineering Thesis 21 April 2015 Abstract Author(s) Chi Pham Ngoc Lan Title Apply Lean thinking in project management Number of Pages 47 pages + 3 appendices Date 5 May 2010 Degree Bachelor of Engineering Degree Programme Media Engineering Specialisation option Audio Visual Technology, Quality Management Instructor(s) Aarne Klemetti, Senior Lecturer The purpose of this thesis was to study the effects of Lean Thinking in Project Manage- ment and how applying Lean Project Management could enhance the productivity of pro- ject work. The study was carried using theoretical research and collecting empirical data from three interviews and one case study at a local company. At the end of the study, the major project management problems at the company were identified and analyzed following Lean Principles. It was also pointed out where there is a need to adjust and modify Lean Thinking in order to efficiently apply it in project work. The case study also demonstrates the intinital effects of using Lean tools in more dynamic en- vironment as marketing projects. The results of this study show how using Lean principles can solve problems in project management activities, demonstrate the potential and suggest a suitable approach to ap- plying Lean Thinking in business. Keywords project management, Lean thinking, Lean principles, Kan- ban, waste, Mura, Muri, Muda Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Methodology 3 2.1