EAFONSI Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Proposed Action Is Located in Winston County, Alabama

U. S. Forest Service Bankhead National Forest Biological Evaluation of Proposed Salvage of Forestland Damaged by Hurricane Rita – 2006 Winston County, Alabama This proposed action is located in Winston County, Alabama. Contact: Glen D. Gaines District Ranger P. O. Box 278 Double Springs, Alabama 35553 Telephone 205-489-5111 FAX 205-489-3427 E-mail [email protected] Summary: Hurricane Rita came through Bankhead National Forest on September of 2005. Several areas within the Bankhead National Forest received damage from high winds associated with the storm. Stands of hardwood and pine trees were uprooted, broken, blown over and root sprung in the areas covered by this evaluation. The damaged, merchantable timber within these three areas is proposed for removal using a Salvage Timber sale. These areas vary in both cover type and age class but are primarily a mixture of mature pine and hardwoods. The salvage timber sale proposed for implementation under this proposal covers an estimated 97 acres over at least three sites. Sites have been proposed for salvage operations south of Fairview in Winston County (see attached map identified as Figure #1). As with any Forest Service activity, considerations of the potential impacts to environmental resources of this project were evaluated. Some of the protected species of plants and wildlife that could potentially be impacted by these activities include those plant communities found in upland areas, riparian areas, streams and those found on rock outcrops. No incidental take of any federally listed species is expected or anticipated with this proposed action. Proposed salvage sale areas were initially located, then reviewed by biological staff. -

Biological Evaluation of Proposed Salvage of Forestland Damaged by Storm on March 01, 2007 Winston County, Alabama

U. S. Forest Service Bankhead National Forest Biological Evaluation of Proposed Salvage of Forestland Damaged by Storm on March 01, 2007 Winston County, Alabama BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION of Proposed, Endangered, Threatened, and Sensitive Species March 01, 2007 Storm Salvage & Restoration of Forest Cover Winston County, Alabama Bankhead National Forest Responsible Agency: USDA Forest Service National Forests in Alabama William B. Bankhead Ranger District Contact: Deciding Officer: District Ranger, Glen D. Gaines BE Preparer: District Wildlife Biologist, Tom Counts Mailing Address P. O. Box 278 Double Springs, Alabama 35553 Telephone 205-489-5111 FAX 205-489-3427 E-mail [email protected] or [email protected] U. S. Forest Service Bankhead National Forest Biological Evaluation of Proposed Salvage of Forestland Damaged by Storm on March 01, 2007 Winston County, Alabama Location and Approximate Size of Project Areas FS Road # 135 D - 18 acres Section -27 / Township –11 South / Range – 7 West Watershed Lewis Smith Lake FS Road # 112 B (PeninsulaTract) - 13 acres Section -22 / Township -11 South / Range -7 West Watershed Lewis Smith Lake FS Road #135C1 – 26 acres Section – 28 / Township – 11 South / Range 7 West Watershed Lewis Smith Lake FS Road #117D – 29 acres Section 31, 32 / Township 11 South / Range 7 West Watershed Lewis Smith Lake U. S. Forest Service Bankhead National Forest Biological Evaluation of Proposed Salvage of Forestland Damaged by Storm on March 01, 2007 Winston County, Alabama This proposed action is located in Winston County, Alabama. Contact: Glen D. Gaines District Ranger P. O. Box 278 Double Springs, Alabama 35553 Telephone 205-489-5111 FAX 205-489-3427 E-mail [email protected] Summary: A series of strong storms swept through Alabama and Georgia on March 1, 2007. -

Camp Mcdowell Project FERC Project No

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR SMALL HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT EXEMPTION Camp McDowell Project FERC Project No. 14793-000 Alabama Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Office of Energy Projects Division of Hydropower Licensing 888 First Street, NE Washington, D.C. 20426 February 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 APPLICATION ............................................................................................................ 1 2.0 PURPOSE OF ACTION AND NEED FOR POWER ................................................ 1 2.1 Purpose of Action ................................................................................... 1 2.2 Need for Power ....................................................................................... 1 3.0 PROPOSED ACTION AND ALTERNATIVES ......................................................... 3 3.1 Proposed Action ............................................................................................ 3 3.1.1 Project Description .............................................................................. 3 3.1.2 Project Operation ................................................................................. 4 3.1.3 Proposed Measures .............................................................................. 4 3.2 Section 30(C) Conditions .............................................................................. 5 3.3 Additional Staff-recommended Measures ..................................................... 5 3.4 No-Action Alternative .................................................................................. -

United States of America Federal Energy

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION Alabama Power Company Project No. 2 165-029 NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY OF ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (March 1.2011) In accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s regulations, 18 C.F.R. Part 380, the Office of Energy Projects has reviewed an application filed by Alabama Power Company on June 5, 2009. requesting Commission approval to permit Mr. Lynn Layton (permittee) to construct and operate three covered 10-slip boat docks and a concrete patio at Cushman’s Marina, located on the Lewis Smith Development of the Warrior River Project (FERC No. 2165). The Lewis Smith Development is located on the headwaters of the Black Warrior River on the Sipsey Fork in Cullman, Walker, and Winston Counties, Alabama, and occupies 2,691.44 acres of federal lands administered by the U.S. Forest Service. An environmental assessment lEA) has been prepared as a part of Commission staff’s review. The EA evaluates the environmental impacts that would result from approving the licensee’s proposal and alternatives, and finds that approval of the application would not constitute a major federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment. A copy of the EA is on file with the Commission and is available for public inspection. The EA may also be viewed on the Commission’s website at yyy,.f.çrçoy using the “eLibrary” link. Enter the docket number (P-2165) excluding the last three digits in the docket number field to access the document. For assistance, contact FERC Online Support at FERCOnhineSupport(à),ferc.gov or toll-free at 1-866-208-3676, or for TTY, (202) 502-8659. -

German Guide to ALABAMA

German Guide to ALABAMA A publication of September, 2014 Table of Contents 1. Message from AlabamaGermany Partnership 2. Message from the Governor 3. The State of Alabama 3.1 Overview 3.2 Geography 3.3 Climate/Weather 3.4 Demographics 4. Guide to Alabama Living 4.1 Sports & Leisure 4.2 Emergency Procedures 4.3 Insurance 4.4 Health Care 4.5 Weather Alerts 4.6 Financial & Banking 4.7 Housing 4.8 Utilities & Garbage 4.9 Shopping 4.10 Churches and Religion 4.11 Public Transit 4.12 Educational System 4.13 Holidays 4.14 Entertainment 4.15 Celebrations 4.16 Alcohol Sales 4.17 Etiquette 4.18 Southern Language 4.19 Volunteerism 4.20 German Restaurants, Clubs and Influence in Alabama 5. Government & Issuance 5.1 Social Security 5.2 Taxes 5.3 Automobile license 5.4 Recording Events (Birth, death, etc.) 6. Doing Business in Alabama 7. Major City Guide and Tourist Attractions 7.1 Alabama Beaches 7.2 Auburn/Opelika Area 7.3 Birmingham Area 7.4 Huntsville/Decatur & Cullman Area 7.5 Mobile Area 7.6 Montgomery Area 7.7 Pell City Area 7.8 Tuscaloosa Area 8. Appendix 8.1 AGP Board of Directors 8.2 German Companies in Alabama 8.3 Southern English Guide 1. Welcome to our beautiful state of Alabama! An interest in improving relations between Alabama and Germany began in 1993, when Mercedes-Benz began looking at Alabama as a site for its new North American plant. Many organizations, agencies, corporations and individuals joined together to present Alabama as “the” place to locate the Mercedes-Benz US International (MBUSI) car plant. -

Lewis Smith Lake Transition Zone Project Progress Report

Lewis Smith Lake Transition Zone Project Progress Report 2012-2013 Report prepared by: Craig Roghair1, John Moran2, Colin Krause1, and C. Andrew Dolloff1 March 2014 1USDA Forest Service 2USDA Forest Service Southern Research Station National Forests in Alabama Center for Aquatic Technology Transfer 2946 Chestnut St 1710 Research Center Dr. Montgomery, AL 36107 Blacksburg, VA 24060 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Transition zone delineation ...................................................................................................................... 5 Sample reach selection ............................................................................................................................. 5 Fish sampling ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Boat electrofishing ................................................................................................................................ 6 Mini-trawl.............................................................................................................................................. 6 Mainstem backpack electrofishing ...................................................................................................... -

Brushy Creek Watershed Water Quality Assessment Report

Brushy Creek Watershed Water Quality Assessment Report Environmental Indicators Section Field Operations Division Alabama Department of Environmental Management Brushy Creek Watershed Water Quality Assessment Report January 14, 1999 Environmental Indicators Section Field Operations Division Alabama Department of Environmental Management Brushy Creek Watershed Water Quality Assessment Preface This project was funded or partially funded by the Alabama Department of Environmental Management utilizing a Clean Water Act Section 319(h) nonpoint source demonstration grant provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency - Region 4. Comments or questions related to this report should be addressed to: Alabama Department of Environmental Management Field Operations Division Environmental Indicators Section P.O. Box 301463 Montgomery, AL 36130-1463 Executive Summary Brushy Creek is located in Lawrence County and Winston County, Alabama and is one of the major tributaries to Lewis Smith Reservoir. The drainage area of Brushy Creek is 227.4 km2 (87.8 mi2). In recent years, concerns have developed among area residents concerning the lack of water quality data from Brushy Creek and it’s embayment in Smith Reservoir, which serves as the water supply for the community of Arley, Alabama. Determinations of landuse as well as measurements of water quality and estimates of nutrient loading attempt to address those concerns. Tributary nutrient loading data for other major tributaries to Smith Reservoir was collected for ADEM by Auburn University during the Clean Lakes Program Phase I Diagnostic / Feasibility Study of Smith Reservoir. This report is intended to serve as a companion document to the Phase I study’s final report (ADEM 1998). Much of the Brushy Creek watershed lies within the Bankhead National Forest and is forested with an even mix of deciduous forest, evergreen forest, and mixed forest. -

Flattened Musk Turtle (Sternotherus Depressus) 5-Year Review

Flattened Musk Turtle (Sternotherus depressus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Photograph of an adult and juvenile flattened musk turtle (United States Geological Survey). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Mississippi Ecological Services Field Office Jackson, Mississippi 1 5-YEAR REVIEW Flattened musk turtle (Sternotherus depressus) I. GENERAL INFORMATION A. Methodology used to complete the review: In conducting this 5-year review, we relied on the best available information pertaining to historic and current distributions, life history, and habitats of this species. We announced initiation of this review and requested information in a published Federal Register notice with a 60-day comment period (74 FR 31972). We conducted an internet search, reviewed all information in our files, and solicited information from all knowledgeable individuals including those associated with academia and State conservation programs. Our sources include the final rule listing for this species under the Act; the recovery plan; peer reviewed scientific publications; unpublished field observations by Service, State and other experienced biologists; unpublished survey reports; and notes and communications from other qualified biologists or experts. The completed draft was sent to the other cooperating Service office and three peer reviewers for review. Comments were evaluated and incorporated into this final document as appropriate (see Appendix A). We did not receive any public comments during the 60-day open comment period. B. Reviewers Lead Region – Southeast Region: Kelly Bibb, 404-679-7132 Lead Field Office –Mississippi, Ecological Services: Daniel J. Drennen, 601-321-1127 Cooperating Field Office - Alabama, Ecological Services: Jeff Powell, 251-441-5858 C. Background 1. -

Hydrology of Area 22, Eastern Coal Province, Alabama New York

HYDROLOGY OF AREA 22, EASTERN COAL PROVINCE, ALABAMA NEW YORK MULBERRY FORK LOCUST FORK SIPSEY FORK PENNSYLVANIA BEAR CREEK NORTH CAROLINA (SOUTH CAROLINA \ ALABAMA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-RESOURCES INVESTIGATIONS OPEN-FILE REPORT 81-135 HYDROLOGY OF AREA 22, EASTERN COAL PROVINCE, ALABAMA BY JOE R. HARK1NS AND OTHERS U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-RESOURCES INVESTIGATIONS 81-135 TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA MARCH 1981 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Doyle G. Frederick, Acting Director For additional information write to: U. S. Geological Survey P. O. Box V University, Alabama 35486 CONTENTS Page Abstract .................................................... 1 1.0 Introduction ..................................................................... 2 1.1 Objective .................................................................... 2 F. A. Kilpatrick and J. R. Rollo 1.2 Project area. ................................................................. .4 Joe R. Harkins 1.3 Hydrologic problems related to surface mining. .......................................... .6 Celso Puente 2.0 General features. ................................................................. .8 2.1 Geology .................................................................... .8 A. K. Sparkes 2.2 Land forms .................................................................. 10 A. K. Sparkes 2.3 Surface drainage. .............................................................. 12 Joe R. Harkins -

Loft 212 the Atrium of Cullman

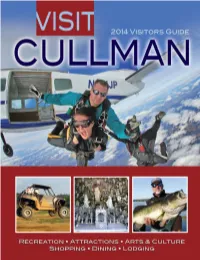

WWW.VISITCULLMAN.ORG 2 VISIT CULLMAN | 2014 1531610 WWW.VISITCULLMAN.ORG 3 VISIT CULLMAN | 2014 5 Welcome to Cullman 6 Tourism Board 7 And the Rest is History… 9 Cullman County Museum 11 Guy Hunt Museum & Library Cover Information: Skydiving photo provided by Soulcameraflyer. Stony 13 Peinhardt Farm Lonesome photo provided by Cullman County Parks & 14 North Alabama Agriplex Rec. All other cover photos contributed. 17 Smith Lake questions? contact: 20 Sportsman Lake Park Cullman Area Chamber of Commerce & Visitor Center 22 Clarkson Covered Bridge 256-734-0454 | 1-800-313-5114 • [email protected] | VisitCullman.org 24 Crooked Creek Civil War Museum Published by The Cullman Times 26 Downtown Cullman 300 4th Ave NE, Cullman | 256-734-2131 | CullmanTimes.com 28 Calendar of Events Layout by Jessica Wells 29 Downtown Mural Project 32 Rock the South 36 Shopping 40 Dining in Cullman 42 Restaurant Directory 46 Visiting the Shrine 48 The Grotto 50 Fairs & Festivals 54 Farm Y’all 56 Oktoberfest 58 Bass Fishing Hall of Fame 60 Festhalle Market Platz 62 The Evelyn Burrow Museum 66 Golf Courses Plentiful 70 Skydive Alabama 71 Hurricane Creek Park 72 Stony Lonesome OHV Park 74 Cullman Venues 78 Heritage Park 79 Field of Miracles 80 Cullman Wellness & Aquatics Center 81 City Parks & Recreation 82 Lodging Directory WWW.VISITCULLMAN.ORG 4 VISIT CULLMAN | 2014 Welcome to Cullman In Cullman, we make every effort to greet our guests with warmth to 5 p.m. Our staff can help you find lodging in the area, recom- and a spirit of welcoming. If you are thinking about visiting Cull- mend delicious restaurants, offer a list of unique attractions and man for the first time, you can expect friendly faces and an expe- fun entertainment events that are going on, and just simply offer rience like none other. -

Alabama Power Company Birmingham, Alabama

ALABAMA POWER COMPANY BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA COOSA AND WARRIOR RIVER PROJECTS E6 – THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES DATABASE SUMMARY REPORT APRIL 2004 Prepared by: ALABAMA POWER COMPANY BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA COOSA AND WARRIOR RIVER PROJECTS E6 – THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES DATABASE SUMMARY REPORT APRIL 2004 Prepared by: ALABAMA POWER COMPANY BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA COOSA AND WARRIOR RIVER PROJECTS E6 – THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES DATABASE SUMMARY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1-1 2.0 DATABASE DEVELOPMENT AND MAINTENANCE..................................2-1 2.1 Content and Geographic Scope........................................................................2-1 2.2 Database Sources.............................................................................................2-2 2.3 Data Reconciliation..........................................................................................2-5 2.4 Maintenance.....................................................................................................2-6 3.0 DATABASE SPECIES SUMMARY..................................................................3-1 3.1 Coosa River Basin............................................................................................3-1 3.2 Black Warrior River Basin...............................................................................3-1 3.3 Alabama River Basin .......................................................................................3-1 -

I-65 @ Exit 305 (Cr 222) Access Concept Plan

I-65 @ EXIT 305 (CR 222) ACCESS CONCEPT PLAN Developed for: The City of Good Hope & The City of Cullman Prepared by: JUNE 13, 2017 I-65 @ EXIT 305 (CR 222) ACCESS CONCEPT PLAN Developed for: The City of Good Hope 135 Municipal Drive Cullman, Alabama 35057 256.739.3757 and The City of Cullman 204 2nd Avenue, NE Cullman, Alabama 35055 P.O. Box 278 Cullman, Alabama 35056 256.775.7102 Prepared by: Skipper Consulting, Inc. 3644 Vann Road, Suite 100 Birmingham, Alabama 35235 205.655.8855 JUNE 13, 2017 skipperinc.com I-65 at Exit 305 (CR 222) Vicinity Access Concept Plan Good Hope, Alabama TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 2.0 PROJECT HISTORY AND BACKGROUND ............................................................. 2 3.0 EXISTING CONDITIONS ...................................................................................... 3 3.1 Project Study Area ........................................................................................ 3 3.2 Study Area Roadways And Intersections ......................................................... 4 3.3 Existing Segment Traffic Volumes .................................................................. 7 3.4 Existing Roadway Segment Capacity Analysis .................................................. 9 3.5 Existing Land Uses and Zoning ...................................................................... 9 4.0 FUTURE CONDITIONS AND ACCESS CONCEPT STRATEGY ............................... 12 4.1 Future