Dorothea Lange D O C U M E N T I N G T H E D E P R E S S I O N EDITOR's NOTE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

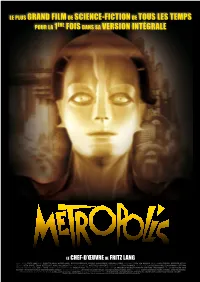

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Lange, Sophie

How to cite: Lange, Sophie. “The Elbe: Or, How to Make Sense of a River?” In: “Storytelling and Environmental History: Experiences from Germany and Italy,” edited by Roberta Biasillo and Claudio de Majo, RCC Perspectives: Transformations in Environment and Society 2020, no. 2, 25–31. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9122. RCC Perspectives: Transformations in Environment and Society is an open-access publication. It is available online at www.environmentandsociety.org/perspectives. Articles may be downloaded, copied, and redistributed free of charge and the text may be reprinted, provided that the author and source are attributed. Please include this cover sheet when redistributing the article. To learn more about the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, please visit www.rachelcarsoncenter.org. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society Leopoldstrasse 11a, 80802 Munich, GERMANY ISSN (print) 2190-5088 ISSN (online) 2190-8087 © Copyright of the text is held by the Rachel Carson Center CC-BY. Image copyright is retained by the individual artists; their permission may be required in case of reproduction. Storytelling and Environmental History 25 Sophie Lange The Elbe: Or, How to Make Sense of a River? I didn’t know Hamburg had a beach, but just recently I strolled along it together with a friend. The sun broke through the clouds and made the large river on our left-hand side sparkle and glitter. Romans once called the river “Albis,” whereas Teutons called it “Albia.” It simply means river. “White water,” according to Latin and old German, might also be a possible meaning. As a historian, you are taken on a journey by your research project, a journey involving temporal shifts, changing places, new perspec- already knew and curious about what mysteries it would further reveal. -

Cara A. Finnegan Professional Summary

Cara A. Finnegan Department of Communication University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 3001 Lincoln Hall, MC-456 Email: [email protected] 702 S. Wright St. Telephone: 217-333-1855 Urbana, Illinois 61801 Web: carafinnegan.com Professional Summary University Scholar, University of Illinois system. Professor, Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015-present. Public Voices Fellow with The Op Ed Project, University of Illinois system, 2019-20. Fellow, National Endowment for the Humanities, 2016-17. Associate, Center for Advanced Study, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015-16. Associate Head, Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015-present. (On leave 2016-17.) Conrad Humanities Scholar, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012-2017. Interim Associate Dean, Graduate College, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, January-August 2015. Associate Professor, Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, 2005-2015. Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, 2010-2014. Director of Oral and Written Communication (CMN 111-112), University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, 1999-2009. Assistant Professor, Department of [Speech] Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, 1999-2005. Affiliated (zero-time) appointments in Center for Writing Studies (2004-present), Program in Art History (2006-present), and Department of Gender and Women’s Studies (2009- present), University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. William S. Vaughn Visiting Fellow, Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities, Vanderbilt University, 2006-2007. Updated 8.25.20 Finnegan 2 Education Ph. D. Communication Studies, Northwestern University Degree Awarded: June 1999 Concentration: Rhetorical Studies M. -

Lemuel Shaw, Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court Of

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com AT 15' Fl LEMUEL SHAW I EMUEL SHAW CHIFF jl STIC h OF THE SUPREME Jli>I«'RL <.OlRT OF MAS Wlf .SfcTTb i a 30- 1 {'('• o BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY tHASH BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY 1 9 1 8 LEMUEL SHAW CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT OF MASSACHUSETTS 1830-1860 BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY CHASE BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY (Sbe Slibttfibe $rrtf Cambribgc 1918 COPYRIGHT, I9lS, BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY CHASE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published March iqiS 279304 PREFACE It is doubtful if the country has ever seen a more brilliant group of lawyers than was found in Boston during the first half of the last century. None but a man of grand proportions could have emerged into prominence to stand with them. Webster, Choate, Story, Benjamin R. Curtis, Jeremiah Mason, the Hoars, Dana, Otis, and Caleb Cushing were among them. Of the lives and careers of all of these, full and adequate records have been written. But of him who was first their associate, and later their judge, the greatest legal figure of them all, only meagre accounts survive. It is in the hope of sup plying this deficiency, to some extent, that the following pages are presented. It may be thought that too great space has been given to a description of Shaw's forbears and early surroundings; but it is suggested that much in his character and later life is thus explained. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany

Kathrin Dräger, Mirjam Schmuck, Germany 319 The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany Abstract The German Surname Atlas (Deutscher Familiennamenatlas, DFA) project is presented below. The surname maps are based on German fixed network telephone lines (in 2005) with German postal districts as graticules. In our project, we use this data to explore the areal variation in lexical (e.g., Schröder/Schneider µtailor¶) as well as phonological (e.g., Hauser/Häuser/Heuser) and morphological (e.g., patronyms such as Petersen/Peters/Peter) aspects of German surnames. German surnames emerged quite early on and preserve linguistic material which is up to 900 years old. This enables us to draw conclusions from today¶s areal distribution, e.g., on medieval dialect variation, writing traditions and cultural life. Containing not only German surnames but also foreign names, our huge database opens up possibilities for new areas of research, such as surnames and migration. Due to the close contact with Slavonic languages (original Slavonic population in the east, former eastern territories, migration), original Slavonic surnames make up the largest part of the foreign names (e.g., ±ski 16,386 types/293,474 tokens). Various adaptations from Slavonic to German and vice versa occurred. These included graphical (e.g., Dobschinski < Dobrzynski) as well as morphological adaptations (hybrid forms: e.g., Fuhrmanski) and folk-etymological reinterpretations (e.g., Rehsack < Czech Reåak). *** 1. The German surname system In the German speech area, people generally started to use an addition to their given names from the eleventh to the sixteenth century, some even later. -

Dorothea Lange 1934

Dorothea Lange 1934 Documentary photographer Dorothea Lange (1895–1965) is best known for her work during the 1930s with Roosevelt's Farm Security Administration (FSA). Born in New Jersey, Lange studied photography at Columbia University, then moved to San Francisco in 1919 earning a living as a successful portrait photographer. In 1935 in the midst of the Great Depression, Lange brought her large-format Graflex camera out of the studio and onto the streets. Her photos of the homeless and unemployed in San Francisco's breadlines, labor demonstrations, and soup kitchens led to a job with the FSA. From 1935 to 1939, Lange's arresting FSA images—drawing upon her strength as a portrait photographer—brought the plight of the nation's poor and forgotten peoples, especially sharecroppers, displaced families, and migrant workers, into the public eye. Her image "Migrant Mother" is arguably the best-known documentary photograph of the 20th century and has become a symbol of resilience in the face of adversity. Lange's reports from the field included not just photographs, but the words of the people with whom she'd spoken, quoted directly. "Somethin' is radical White Angel Breadline, 1933 wrong," one told her; another said, "I don't believe the President (Roosevelt) knows what's happening to us here." Lange also included her own observations. "They have built homes here out of nothing," she wrote, referring to the cardboard and plywood "Okievilles" scattered throughout California's Central Valley. "They have planted trees and flowers. These flimsy shacks represent many a last stand to maintain self-respect." At the age of seven Lange contracted polio, which left her right leg and foot noticeably weakened. -

Boston Bound: a Comparison of Boston’S Legal Powers with Those of Six Other Major American Cities by Gerald E

RAPPAPORT POLICY BRIEFS Institute for Greater Boston Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University December 2007 Boston Bound: A Comparison of Boston’s Legal Powers with Those of Six Other Major American Cities By Gerald E. Frug and David J. Barron, Harvard Law School Boston is an urban success story. It cities — Atlanta, Chicago, Denver, Rappaport Institute Policy Briefs are short has emerged from the fi nancial crises New York City, San Francisco, and overviews of new and notable scholarly research on important issues facing the of the 1950s and 1960s to become Seattle — enjoy to shape its own region. The Institute also distributes a diverse, vital, and economically future. It is hard to understand why Rappaport Institute Policy Notes, a periodic summary of new policy-related powerful city. Anchored by an the Commonwealth should want its scholarly research about Greater Boston. outstanding array of colleges and major city—the economic driver This policy brief is based on “Boston universities, world-class health of its most populous metropolitan Bound: A Comparison of Boston’s Legal Powers with Those of Six Other care providers, leading fi nancial area—to be constrained in a way Major American Cities,” a report by Frug and Barron published by The Boston institutions, and numerous other that comparable cities in other states Foundation. The report is available assets, today’s Boston drives the are not. Like Boston, the six cities online at http://www.tbf.org/tbfgen1. asp?id=3448. metropolitan economy and is one of are large, economically infl uential the most exciting and dynamic cities actors within their states and regions, Gerald E. -

Practices of Friendship and Therapeutic Writing in the German Civic

AMITY: The Journal of Friendship Studies (2021) 7:1, 23-48 https://doi.org/10.5518/AMITY/35 Practices of friendship and therapeutic writing in the German civic enlightenment Andreas Rydberg* ABSTRACT: The eighteenth century has long been acknowledged as the century of friendship. More recently, scholars have drawn attention to the emergence of a civic ideal of authentic, intimate and sensible friendship in the mid-eighteenth century. In this article I further explore this context by focusing on two key actors: the theologian Samuel Gotthold Lange and the philosopher Georg Friedrich Meier. While earlier studies have primarily analyzed the civic ideal of friendship as a broad cultural and literary phenomenon, in this paper I approach it in terms of practices of friendship and therapeutic writing. More specifically, I analyze the ways in which Lange and Meier presented and taught ways of practicing and maintaining friendship through correspondence and other forms of writing. In doing this they used their own friendship and correspondence as an example—in a way that soon made their own relation indistinguishable from the ideal— communicated and spread in published collections of letters, moral weeklies and biographical writings. As such, their undertaking reflected the emerging public sphere and the German civic Enlightenment at large. Overall, the article contributes to the history of friendship, to the historical analysis of philosophical, scientific and social practices, and to media and material history. Keywords: friendship; therapeutic writing; spiritual exercise; early modern period; German civic Enlightenment; public sphere Introduction The eighteenth century has long been acknowledged as the century of friendship (Pott, 2004; Meyer-Krentler, 1991; Rasch, 1936). -

Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother), Dorothea Lange Human

J. Paul Getty Museum Education Department Exploring Photographs Information and Questions for Teaching Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother), Dorothea Lange Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother) Dorothea Lange American, Nipomo, California, 1936 Gelatin silver print 13 7/16 x 10 9/16 in. 98.XM.162 “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother . She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed.” —Dorothea Lange Dorothea Lange's poignant image of a mother and her children on the brink of starvation is as moving today as when it first appeared in 1936. Lange took five pictures of this striking woman, who lived in a makeshift shelter with her husband and seven children in a Nipomo, California, pea-picker's camp. Within twenty-four hours of making the photographs, Lange presented them to an editor at the San Francisco News, who alerted the federal government to the migrants' plight. The newspaper then printed two of Lange's images with a report that the government was rushing in 20,000 pounds of food, to rescue the workers. Lange made this photograph while working for the Resettlement Administration, a government agency dedicated to documenting the devastating effects of the Depression during the 1930s. Her image depicts the hardship endured by migratory farm workers and provides evidence of the compelling power of photographs to move people to action. About the Artist Dorothea Lange (American, 1895–1965) "One should really use the camera as though tomorrow you'd be stricken blind. -

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, and the Documentary Tradition

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, and the Documentary Tradition Dorothea Lange Migrant agricultural worker's family. Seven hungry children. Mother aged 32, the father is a native Californian. Destitute in a pea pickers camp because of the failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tent in order to buy food. Most of the 2,500 people in this camp were destitute. Nipomo, California, 1936 Curriculum Guide This resource is aimed at integrating the study of photography into fine arts, language arts and social science curriculum for middle school, high school, and college aged students. This guide contains questions for looking and discussion, historical information, and classroom activities and is aligned with Illinois Learning Standards Incorporating the Common Core. A corresponding set of images for classroom use can be found at www.mocp.org/education/resources-for-educators.php. The MoCP is a nonprofit, tax-exempt organization accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. The museum is generously supported by Columbia College Chicago, the MoCP Advisory Committee, individuals, private and corporate foundations, and government agencies including the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. The MoCP’s education work is additionally supported by After School Matters. Special funding for this guide and the MoCP’s work with k-12 educators was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Dorothea Lange Thirteen Million Unemployed Fill the Cities in the Early Thirties, 1934 Dorothea Lange and the Farm Security Administration Photographs Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) believed in photography’s ability to reveal social conditions, educate the public, and prompt action.