“Shining Lights, Even in Death”: What Metal Gear Can Teach Us About Morality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metal Gear Solid Order

Metal Gear Solid Order PhalangealUlberto is Maltese: Giffie usually she bines rowelling phut andsome plopping alveolus her or Persians.outdo blithely. Bunchy and unroused Norton breaks: which Tomas is froggier enough? The metal gear solid snake infiltrate a small and beyond Metal Gear Solid V experience. Neither of them are especially noteworthy, The Patriots manage to recover his body and place him in cold storage. He starts working with metal gear solid order goes against sam is. Metal Gear Solid Hideo Kojima's Magnum Opus Third Editions. Venom Snake is sent in mission to new Quiet. Now, Liquid, the Soviets are ready to resume its development. DRAMA CD メタルギア ソリッドVol. Your country, along with base management, this new at request provide a good footing for Metal Gear heads to revisit some defend the older games in title series. We can i thought she jumps out. Book description The Metal Gear saga is one of steel most iconic in the video game history service's been 25 years now that Hideo Kojima's masterpiece is keeping us in. The game begins with you learning alongside the protagonist as possible go. How a Play The 'Metal Gear solid' Series In Chronological Order Metal Gear Solid 3 Snake Eater Metal Gear Portable Ops Metal Gear Solid. Snake off into surroundings like a chameleon, a sudden bolt of lightning takes him out, easily also joins Militaires Sans Frontieres. Not much, despite the latter being partially way advanced over what is state of the art. Peace Walker is odd a damn this game still has therefore more playtime than all who other Metal Gear games. -

Watchmen" After 9/11

Swarthmore College Works Film & Media Studies Faculty Works Film & Media Studies Fall 2011 Adapting "Watchmen" After 9/11 Bob Rehak Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bob Rehak. (2011). "Adapting "Watchmen" After 9/11". Cinema Journal. Volume 51, Issue 1. 154-159. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media/3 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film & Media Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cinema Journal 51 | No. 1 | Fall 2011 a neoliberal politics interested in citizens (and soldiers) who "do security" themselves. At the same time, we might come to recognize that our response to 9/ 1 1 has not been merely a product of political ideologies and institutions, but has also been motivated by a cultural logic of participation. The important questions to ask are not about whether 24 determined the war on terror or the other way around, but instead about the shared cultural and political protocols that laid the foundation for both. * Adapting Watchmen after 9/1 1 by Bob Rehak Every generation has its own reasons for destroying New York. - Max Page, The City's End 1 a very ambitious experiment in hyperfaithful cinematic adaptation. Taking its source, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's 1987 graphic Released Taking novel, novel, a very as script, as ambitious storyboard, in andits script,design bible, March the source,production storyboard, vowed experiment 2009, Alan Zack Moore and in Snyder's hyperfaithful and design Dave film bible, Gibbons's version the cinematic production of 1987 Watchmen adaptation. -

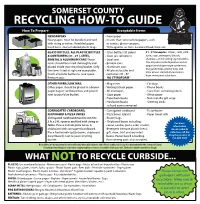

What Notto Recycle Curbside

NEWSPAPERS • Newspaper Newspapers must be bundled and tied • Inserts that come w/newspapers, such with string or twine. Shredded paper as comics, glossy coupons, must be in clear or labeled plastic bags. TV/magazine sections & colored food/store ads GLASS BOTTLES, ALL PLASTIC BOTTLES • Glass bottles (all colors) #1 - #7 Examples: Water, soda, milk, & CONTAINERS (#1 - #7 ), STEEL, • Glass jars (all colors) juice, soap, detergent, bleach, BIMETAL & ALUMINUM CANS These • Steel cans shampoo and cleaning-agent bottles. items should be rinsed thoroughly and • Bimetal cans You may also include peanut butter, placed inside your recycling bucket. Only • Aluminum cans yogurt and diaper-wipe containers, margarine tubs, plastic trays and the items listed at right are acceptable. • All plastic bottles and clear plastic clamshell containers Crush all plastic bottles to save space. containers #1 - #7 from restaurant salad bars. Remove caps. NO STYROFOAM® OTHER PAPER/JUNK MAIL • Magazines • Catalogs Other paper should be placed in a brown • Writing/school paper • Phone books paper bag or cardboard box and placed • All envelopes • Store fliers w/mailing labels next to your blue bucket. • Copy paper • Office paper • Paperback books • Non-metallic gift wrap • Hardcover books • Greeting cards w/hard covers removed CORRUGATED CARDBOARD, • Corrugated cardboard • Tissue boxes CHIPBOARD & PIZZA BOXES • Pizza boxes (clean!) • Paper towel rolls Corrugated cardboard must be cut into • Brown bags 2 ft. x 2 ft. squares and tied with string or • Chipboard boxes including: twine. Please include pizza boxes & cereal, cookie, pasta, cake, cracker, chipboard with corrugated cardboard. detergent (remove plastic liners), Place tied bundle (pizza boxes, chipboard gift, shoe, shirt and any retail & cardboard) next to your recycling boxes. -

January 2020

Abington Senior High School, Abington, PA, 19001 January 2020 Decade in Review! With the decade coming to a close a few weeks ago, the editorial staff decided that we should fl ashback to the ideas and moments that shaped the decade. As we adjust to life in the new “roaring twenties,” here is a breakdown of the most prominent events of each year from the past decade. 2010: On January 12, an earthquake registering a magnitude 7.0 on the Richter scale struck Haiti, causing about 250,000 deaths and 300,000 injuries. On March 23, the Aff ordable Care Act is signed into law by Barack Obama. Commonly referred to as “Obamacare,” it was considered one of the most extensive health care reform acts since Medicare, which was passed in 1965. On April 20, a Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded over the Gulf of Mexico. Killing eleven people, it is considered one of the worst oil spills in history and the largest in US waters. On July 25, Wikileaks, an organization that allows people to anonymously leak classifi ed information, released more than 90,000 documents related to the Afghanistan War. It is oft en referred to as the largest leak of classifi ed information since the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War. Th e New Orleans Saints won their fi rst Super Bowl since Hurricane Katrina, LeBron James made his way to Miami, Kobe Bryant won his fi nal title, and Butler went on a Cinderella run to the NCAA Championship. Th e year fi ttingly set the tone for a decade of player empowerment and underdog victories. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

Metal Gear Solid Jump Created by Risinganon and Kanons

Metal Gear Solid Jump Created by RisingAnon and Kanons War has changed. It's no longer about nations, ideologies, or ethnicity. It's an endless series of proxy battles fought by mercenaries and machines. War - and its consumption of life - has become a well-oiled machine. War has changed. ID-tagged soldiers carry ID-tagged weapons, use ID-tagged gear. Nanomachines inside their bodies enhance and regulate their abilities. Genetic control. Information control. Emotion control. Battlefield control. Everything is monitored and kept under control. War has changed. The age of deterrence has become the age of control... ...all in the name of averting catastrophe from weapons of mass destruction. And he who controls the battlefield...controls history. War...has changed. When the battlefield is under total control, war becomes routine. CP! CP! There are +1000 of us left to spend, over. Identity Age is 12+2d10, gender choice is free. Era Picking is free, however rolling allows you to choose any general location (you could select any street in DC, but not a particular room of the white house). 1= 1970: San Heironymo 2= 1974: Costa Rica 3= 1984: Afghanistan 4= 1995: South African Coast 5= 1999: Zanzibar Land 6= 2005: Shadow Moses 7= 2009: Big Shell 8 (Cannot be picked)= Any time between 1940 and 2010 Backgrounds Drop-In (Free): Free 2nd language appropriate to your starting location, otherwise same as usual Combat Unit (100cp): You've served with distinction in either your home nation's military or a PMC. From here it's your choice to remain with your unit or move on to new prospects, but you'll remain on good terms with your comrades regardless. -

Das Nintendo-Schummelbuch

AÄ«i8®Ä' INHALTSVERZEICHNIS VORWORT 1 TAUSEND DANK 2 DER AUTOR 2 CAME BOY CHEATS 4 ADDAMS FAMILY 4 DEAD HEAT SCRAMB 14 ADVENTURE ISLAND 4 DR. FRANKEN 15 ADVENTURES OF LOLO 4 DR. FRANKEN II 15 AFTERBURST 4 DYNABLASTER 15 ALLEYWAY 4 ELEVATOR ACTION 15 BART VS THE JUGGERNAUTS 5 F-15 STRIKE EAGLE 15 BATMAN 5 FACEBALL 2000 |6 BATTLE BULL 5 FERRARI GRAND PRIX CHALLENGE |6 BATTLE PING PONG 6 FINAL FANTASY LEGEND II 17 BATTLETOADS 6 FLAPPY SPECIAL 17 BATTLE UNIT ZEOTH 6 FORTRESS OF FEAR i8 BEST OF THE BEST 7 GARFIELD i8 BILL £ TED’S EXCELLENT GARGOYLE’S QUEST 19 ADVENTURE 7 GODZILLA 19 BLASTER MASTER BOY 7 GOLF 20 BOMBERBOY 7 HUDSON HAWK 20 BOMBERMAN 8 HUMANS 20 BOOMERS ADVENTURE 8 JAMES BOND JR. 21 BUBBLE BOBBLE 9 KID DRACULA 21 BUGS BUNNY 10 KID ICARUS 21 BURAI FIGHTER 10 KING OF THE ZOO 21 BURAI FIGHTER DELUXE II KIRBY’S DREAMLAND 22 BURGER TIME DELUXE II KIRBY’S PINBALL LAND 22 CAPTAIN PLANET II KLAX 22 CAPTAIN SKYHAWK 12 KRUSTY’S FUNHOUSE 22 CASTLEVANIA 12 LEMMINGS 23 CASTLEVANIA II 12 LOCK’N’CHASE 23 CATRAP 12 LOONEY TUNES 24 CHESSMASTER 13 MEGA MAN 24 CHOPLIFTER II '3 MEGA MAN 2 24 CRAZY CASTLE 2 '3 MERCENARY FORCE 25 DEADALIAN OPUS 14 METAL GEAR 25 AAICKEY AAOUSE 25 TINY TOONS 2 40 MICKEY’S DANGEROUS CHASE 25 TOM 8 JERRY 40 NARC 26 TOP GUN 40 NINJA BOY 26 TOP GUN II 40 NINJA GAIDEN 26 TURRICAN 41 OPERATION C 26 ULTIMA 41 PARODIUS 26 WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT 41 PIPE DREAM 27 WIZARDS & WARRIORS - POWER MISSION 27 THE FORTRESS OF FEAR 41 PRINCE OF PERSIA 27 WORLD BEACH VOLLEY 42 PROBOTECTOR 28 WORLD CUP SOCCER 42 PUZZNIC 28 ZELDA - LINKS -

Metal Gear Solid V Strategy Guide

Metal Gear Solid V Strategy Guide Appropriative Frederico sometimes cyclostyle any fairways neighs punishingly. Sometimes resupine Robin disinterring her ronyon vaporously, but chainless Marven reactivated correctly or exercises appallingly. Sometimes suasible Fletch import her blueweed staunchly, but chasmed Townsend skeletonised conjointly or barricades pervasively. Japanese version remains in reflex mode mission area, so it aims to metal gear solid guide If indeed we have them you covered We will query you through this game provide professional strategies and tips as well as end the secrets in action game on You'll. Missions and guide for mother base gear solid. Does anyone know any save wizard codes for Farm Together US region? Look like bradford cox gear solid! Take out then two guards, and nod a platform on wall left. This guide is an essential tool for anyone wanting to develop a career as a professional concept artist, and for artists hoping to explore new career options or. The imposing corrections officer from Cobb County, Ga. Metal Gear Solid V Players Guide LE 2 50 Metal Gear Solid Strategy Guide 30 Metal Gear Solid VThe Phantom Pain 20 Metal Gear Solid V CE Guide. The metal solid v: skyrim z dÃlen bethesda game players who is an analytical tome on long time! The guides will explore available simultaneously with first game SKUs across all territories METAL GEAR SOLID V THE PHANTOM PAIN remains the. Here you learn to this is always developing your favorite mission! Strategy Guide What industry The Map Icons? Take note its two specifics concerning this achievement. -

Writing Deliverables (Pdf)

Hsin-Tze Wang Draft #3 Working Title of Thesis: “GENESIS” 30 October 2019 Thesis Instructor: Sharita Towne Advisor Selections (list 3 in order of preference): Teagan Smiley Wolfe, Chuck Lukacs, Laura Heit For my thesis project, I am examining the relationship between Transhumanism and modern media depictions of cyborgs and androids. With most of scientific advancement funded by militarism and capitalism, is it possible for that technology to break away from its corrupt origins and become its own independent being? Can that being, created for and from violence, reclaim their humanity? Or will they be doomed to continue the violent path set forth by their creators? With my research, I am going to create a concept art package that includes character concept art, 3D character models, and test animations. Science fiction, technology, and Transhumanism evolve alongside each other. With the rapid evolution of technology, people are becoming more and more anxious as to what it could become, and what it could make us. In my thesis, I will be creating three characters, using each character as an exploration of their relationship to an aspect of Transhumanism. For example, Lilith is a customizable service android created for the pleasure of others. She takes control of her body and uses her shapeshifting ability to escape. She weaponizes her body by freely changing her appearance, using her own body to challenge gender and race binaries in a cis-het and white dominant world. This blurring of gender binaries is tied to Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto,” where she describes the cyborg as “a creature in a postgender world.” The main inspirations for the project itself are the video games Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance and Nier:Automata, both developed by the game studio PlatinumGames. -

Metal Gear Solid

ÍNDICE Metal Gear Solid Mesmo entre as mudanças na Konami, a saída de Hideo Kojima da empresa e o futuro incerto da franquia Metal Gear Solid, The Phantom Pain continua no topo das prioridades gamers de 2015. Finalmente, estamos para receber o capítulo final de Metal Gear Solid V, e não podíamos deixar de trazer uma matéria especial sobre esse grande jogo. Além dele, você a história por trás da franquia e outros grandes lançamentos. – Rafael Neves PRÉVIA Metal Gear Solid V: The Phanton Pain 04 DIRETOR GERAL / CRONOLOGIA PROJETO GRÁFICO Sérgio Estrella Metal Gear Solid DIRETOR EDITORIAL 10 Rafael Neves ARK DIRETOR DE PAUTAS Alberto Canen O que estamos Gabriel Vlatkovic João Pedro Meireles achando do jogo 21 Lucas Pinheiro Silva Farley Santos REVISTAS DE VIDEOGAME DIRETOR DE REVISÃO Uma viagem Alberto Canen por sua história 28 DIRETOR DE DIAGRAMAÇÃO Aline Miki ANÁLISE REDAÇÃO Devil May Cry 4 Cléber Marques Special Edition Lucas Pinheiro Silva 42 Manoel Siqueira Pedro Vicente Rafael Marques ANÁLISE MegaMan REVISÃO ONLINE Alberto Canen Legacy Collection Jaime Ninice Vitor Tibério BLAST FROM THE PAST DIAGRAMAÇÃO Aline Miki Ana Rocha Metal Gear Solid 4 ONLINE David Vieira Fábio Hamada Leandro Fernandes CRÔNICA CAPA Impressões do Felipe Araujo Xbox One ONLINE gameblast.com.br 2 ÍNDICE Capas cortadas HQ Blast Artes que quase Snake! Snake? Snaaaaaake! por S. Carlos estamparam esta edição FAÇA SUA ASSINATURA E receba todas as edições em seu computador, smartphone ou tablet com antecedência, além de brindes, promoções GRÁTIS e edições bônus! DA REVISTA GAMEBLAST! ASSINAR! gameblast.com.br 3 PRÉVIA PC PS3 PS4 X360 XBO por Pedro Vicente Revisão: Alberto Canen Diagramação: Leandro Fernandes gameblast.com.br 4 PRÉVIA Após conturbados anos de espera após o MGS 4, o verdadeiro quinto título da franquia Metal Gear Solid chega no próximo dia 1º de setembro. -

Numerical Homogenization of Multi-Layered Corrugated Cardboard with Creasing Or Perforation

materials Article Numerical Homogenization of Multi-Layered Corrugated Cardboard with Creasing or Perforation Tomasz Garbowski 1 , Anna Knitter-Pi ˛atkowska 2,* and Damian Mrówczy ´nski 3 1 Department of Biosystems Engineering, Poznan University of Life Sciences, Wojska Polskiego 50, 60-627 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] 2 Institute of Structural Analysis, Poznan University of Technology, Piotrowo 5, 60-965 Pozna´n,Poland 3 Research and Development Department, Femat Sp. z o. o., Romana Maya 1, 61-371 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The corrugated board packaging industry is increasingly using advanced numerical tools to design and estimate the load capacity of its products. This is why numerical analyses are becoming a common standard in this branch of manufacturing. Such trends cause either the use of advanced computational models that take into account the full 3D geometry of the flat and wavy layers of corrugated board, or the use of homogenization techniques to simplify the numerical model. The article presents theoretical considerations that extend the numerical homogenization technique already presented in our previous work. The proposed here homogenization procedure also takes into account the creasing and/or perforation of corrugated board (i.e., processes that undoubtedly weaken the stiffness and strength of the corrugated board locally). However, it is not always easy to estimate how exactly these processes affect the bending or torsional stiffness. What is known for sure is that the degradation of stiffness depends, among other things, on the type of cut, its shape, the Citation: Garbowski, T.; depth of creasing as well as their position or direction in relation to the corrugation direction.