Madden2019.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studio International Magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’S Editorial Papers 1965-1975

Studio International magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975 Joanna Melvin 49015858 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Joanna Melvin certify that the worK presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this is indicated in the thesis. i Tales from Studio International Magazine: Peter Townsend’s editorial papers, 1965-1975 When Peter Townsend was appointed editor of Studio International in November 1965 it was the longest running British art magazine, founded 1893 as The Studio by Charles Holme with editor Gleeson White. Townsend’s predecessor, GS Whittet adopted the additional International in 1964, devised to stimulate advertising. The change facilitated Townsend’s reinvention of the radical policies of its founder as a magazine for artists with an international outlooK. His decision to appoint an International Advisory Committee as well as a London based Advisory Board show this commitment. Townsend’s editorial in January 1966 declares the magazine’s aim, ‘not to ape’ its ancestor, but ‘rediscover its liveliness.’ He emphasised magazine’s geographical position, poised between Europe and the US, susceptible to the influences of both and wholly committed to neither, it would be alert to what the artists themselves wanted. Townsend’s policy pioneered the magazine’s presentation of new experimental practices and art-for-the-page as well as the magazine as an alternative exhibition site and specially designed artist’s covers. The thesis gives centre stage to a British perspective on international and transatlantic dialogues from 1965-1975, presenting case studies to show the importance of the magazine’s influence achieved through Townsend’s policy of devolving responsibility to artists and Key assistant editors, Charles Harrison, John McEwen, and contributing editor Barbara Reise. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Paul &Bevansky Had an Efibiition Called Inn the Dark a Xdeo

Bruce Nanman will receive the third annual Werner Prize in Columbus, Ohio in May. The $50,000 prize honors an Paul &Bevansky had an efibiition called Inn the Dark A artist who is "consistently original, influential and chdleng- Xdeo BnshiP11aQion in Four Scenes, spread over the four hg to convention." Nauman was preceded by Peter Brook, weeks from 15 February through 15 March 1994 at the theater director, and John Cage, composer and his coi- Sculpture Center, New York City. laborator, the choreogapher, Merce Cunningbarn. Donald dudd, famed minimalist sculptor, died in David Buchan died on 5 January 1994. The whole artists' February at the age of 55. book comuIEityworBdwidehas lost a friend, a colleague and I5etrh-o &BPnscfni, modernist architect famed for the Pan a peerless worker, one who promoted passionately the alter- Am BuHdmg in New York and the Bank of America bugding native media of artists including bookworks, performance, in San Francisco, died in February at the age of 94. video, audio, and multiples, especially when he was working Kathesim Kolta, renowned writer on art and former at Art Metropole from 1975 - 1985. His own assumption of curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, died inJanuary at the various personae such as Lamonte del Monte whose sense age of 89. of style and costume were beyond comparison. David was a Ida Applebroa~ghas created 50 new orighd drawings for true friend of the editor and publisher of this newsletter-- the 150th anniversary of the first pubEcation of Charles someone who helped in times of need, whose generosity was Dickens' A Christmas Carol, published by Arion Press in always there when you needed information, support, San Francisco. -

N.Paradoxa Online Issue 4, Aug 1997

n.paradoxa online, issue 4 August 1997 Editor: Katy Deepwell n.paradoxa online issue no.4 August 1997 ISSN: 1462-0426 1 Published in English as an online edition by KT press, www.ktpress.co.uk, as issue 4, n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal http://www.ktpress.co.uk/pdf/nparadoxaissue4.pdf August 1997, republished in this form: January 2010 ISSN: 1462-0426 All articles are copyright to the author All reproduction & distribution rights reserved to n.paradoxa and KT press. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying and recording, information storage or retrieval, without permission in writing from the editor of n.paradoxa. Views expressed in the online journal are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of the editor or publishers. Editor: [email protected] International Editorial Board: Hilary Robinson, Renee Baert, Janis Jefferies, Joanna Frueh, Hagiwara Hiroko, Olabisi Silva. www.ktpress.co.uk The following article was republished in Volume 1, n.paradoxa (print version) January 1998: N.Paradoxa Interview with Gisela Breitling, Berlin artist and art historian n.paradoxa online issue no.4 August 1997 ISSN: 1462-0426 2 List of Contents Editorial 4 VNS Matrix Bitch Mutant Manifesto 6 Katy Deepwell Documenta X : A Critique 9 Janis Jefferies Autobiographical Patterns 14 Ann Newdigate From Plants to Politics : The Particular History of A Saskatchewan Tapestry 22 Katy Deepwell Reading in Detail: Ndidi Dike Nnadiekwe (Nigeria) 27 N.Paradoxa Interview with Gisela Breitling, Berlin artist and art historian 35 Diary of an Ageing Art Slut 44 n.paradoxa online issue no.4 August 1997 ISSN: 1462-0426 3 Editorial, August 1997 The more things change, the more they stay the same or Plus ca change.. -

L'œuvre Et Ses Contextes

L’œuvre et ses contextes I. Radiguet, le jeune homme à la canne A. Quelques repères biographiques 1903 Raymond Radiguet naît le 18 juin à Saint-Maur. Il quitte l’école communale. Il entre au lycée Charlemagne. 1913 Commence une longue période de lecture et d’écriture de poèmes. 1914 Il est témoin du début de la première guerre mondiale. En avril, dans le train il rencontre Alice, âgée de 24 ans, 1917 mariée à un soldat parti au front. Il devient son amant. Il montre ses premiers vers à André Salmon, poète. Il rencontre Max Jacob et commence à fréquenter les milieux littéraires parisiens. Il publie des poèmes et des contes dans le Canard enchaîné 1918 sous un pseudonyme : Rajky. Il écrit dans une revue avant-gardiste : Sic. Il collabore aux revues Dada de Tristan Tzara et Littérature de André Breton. 1919 Il devient un ami très proche de Jean Cocteau. Le Diable au corps 6 Il assiste au lancement du Bœuf sur le toit, ballet-pantomime de Cocteau et Milhaud Il participe à la création de la revue Le coq. Il écrit avec Cocteau le livret d’un opéra comique intitulé Paul et Virginie, 1920 sur une musique de Satie Il écrit une comédie : Les Pélicans. Il publie sa véritable première œuvre littéraire, un recueil de poésie : les Joues en feu. Il part dans le Var et écrit une nouvelle : Denise. 1921 De retour à Paris, il assiste à la représentation de certaines de ses œuvres. Il commence la rédaction de son premier roman : Le Diable au corps. -

Untitled (Forever), 2017

PUBLISHERS DISTRIBUTED BY D.A.P. SP21 CATALOG CAPTIONS PAGE 6: Georgia O’Keeffe, Series I—No. 3, 1918. Oil on Actes Sud | Archive of Modern Conflict | Arquine | Art / Books | Art Gallery of York board, 20 × 16”. Milwaukee Art Museum. Gift of Jane University | Art Insights | Art Issues Press | Artspace Books | Aspen Art Museum | Atelier Bradley Pettit Foundation and the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. PAGE 7: Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Mesa Éditions | Atlas Press | August Editions | Badlands Unlimited | Berkeley Art Museum | Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II, 1930. Oil on canvas. 24.5 x 36”. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Gift Blank Forms | Bokförlaget Stolpe | Bywater Bros. Editions | Cabinet | Cahiers d’Art of the Burnett Foundation. PAGE 8: (Upper) Emil Bisttram, | Canada | Candela Books | Carnegie Museum Of Art | Carpenter Center | Center For Creative Forces, 1936. Oil on canvas, 36 x 27”. Private collection, Courtesy Aaron Payne Fine Art, Santa Fe. Art, Design and Visual Culture, UMBC | Chris Boot | Circle Books | Contemporary Art (Lower) Raymond Jonson, Casein Tempera No. 1, 1939. Casein on canvas, 22 x 35”. Albuquerque Museum, gift Museum, Houston | Contemporary Art Museum, St Louis | Cooper-Hewitt | Corraini of Rose Silva and Evelyn Gutierrez. PAGE 9: (Upper) The Editions | DABA Press | Damiani | Dancing Foxes Press | Deitch Projects Archive | Sun, c. 1955. Oil on board, 6.2 × 5.5”. Private collection. © Estate of Leonora Carrington. PAGE 10: (Upper left) DelMonico Books | Design Museum | Deste Foundation for Contemporary Art | Dia Hayao Miyazaki, [Woman] imageboard, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). © Studio Ghibli. (Upper right) Center For The Arts | Dis Voir, Editions | Drawing Center | Dumont | Dung Beetle | Hayao Miyazaki, [Castle in the Sky] imageboard, Castle Dust to Digital | Eakins Press | Ediciones Poligrafa | Edition Patrick Frey | Editions in the Sky (1986). -

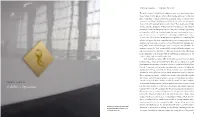

'Seth Price's Operations' by Michael Newman, From

“Here is an operation . ” Seth Price, Was ist los? The walls of several of Seth Price’s exhibitions since 2007 have featured kite- shaped panels in what appears to be a yellow metal—“gold keys,” as the artist likes to call them—with an embossed area in black, white, or various colors, somewhat resembling a leaping figure, which in each picks out the negative shape of a hand dropping keys into another hand. These may be placed high, and are sometimes grouped to form horizontal or vertical friezes.1 The image of passing keys is an everyday gesture raised to the power of a logo, representing an interaction, which may be an exchange, the outcome of a sale or a mort- gage, the loan of a car or an apartment—intimating security, freedom, a place of one’s own. A key also has the metaphorical significance of something that unlocks and opens, lays bare, suggesting the process of interpretation that is applied to the work of art, or a body of work. But is there any meaning, any- thing hidden that needs unlocking? In much contemporary art and culture, the intensive concept of a “deep” meaning has been replaced by the extensive con- cept of networks, nodes that link to other nodes in all directions. The images in the “diamonds” come from tiny GIFs downloaded from the Internet, so the origin is a digital file obtained through a link. In the way that he explores different articulations across various mediums between source, object, and redistribution, Price has developed in an exem- plary manner the experience of an artist born in 1973, and based in New York. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title No such thing as society : : art and the crisis of the European welfare state Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mz626hs Author Lookofsky, Sarah Elsie Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO No Such Thing as Society: Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Sarah Elsie Lookofsky Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Lesley Stern, Co-Chair Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Grant Kester Professor Barbara Kruger 2009 Copyright Sarah Elsie Lookofsky, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Sarah Elsie Lookofsky is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii Dedication For my favorite boys: Daniel, David and Shannon iv Table of Contents Signature Page…….....................................................................................................iii Dedication.....................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents..........................................................................................................v Vita...............................................................................................................................vii -

JEAN COCTEAU (1889-1963) Compiled by Curator Tony Clark, Chevalier Dans L’Ordre Des Arts Et Des Lettres

JEAN COCTEAU (1889-1963) Compiled by curator Tony Clark, Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres 1889 Jean Maurice Clement Cocteau is born to a wealthy family July 5, in Maisons Laffite, on the outskirts of Paris and the Eiffel Tower is completed. 1899 His father commits suicide 1900 - 1902 Enters private school. Creates his first watercolor and signs it “Japh” 1904 Expelled from school and runs away to live in the Red Light district of Marsailles. 1905 - 1908 Returns to Paris and lives with his uncle where he writes and draws constantly. 1907 Proclaims his love for Madeleine Carlier who was 30 years old and turned out to be a famous lesbian. 1908 Published with text and portraits of Sarah Bernhardt in LE TEMOIN. Edouard de Max arranges for the publishing of Cocteau’s first book of poetry ALLADIN’S LAMP. 1909 - 1910 Diaghailev commissions the young Cocteau to create two lithographic posters for the first season of LES BALLETS RUSSES. Cocteau creates illustrations and text published in SCHEHERAZADE and he becomes close friends with Vaslav Nijinsky, Leon Bakst and Igor Stravinsky. 1911 - 1912 Cocteau is commissioned to do the lithographs announcing the second season of LES BALLETS RUSSES. At this point Diaghailev challenges Cocteau with the statement “Etonnez-Moi” - Sock Me. Cocteau created his first ballet libretti for Nijinsky called DAVID. The ballet turned in the production LE DIEU BLU. 1913 - 1915 Writes LE POTOMAK the first “Surrealist” novel. Continues his war journal series call LE MOT or THE WORD. It was to warn the French not to let the Germans take away their liberty or spirit. -

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 Timeline Large Print Guide

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 12 April – 29 August 2016 Timeline Large Print Guide Please return to exhibition entrance Contents 1964 Page 1 1965 Page 3 1966 Page 6 1967 Page 9 1968 Page 12 1969 Page 16 1970 Page 23 1971 Page 30 1972 Page 36 1973 Page 41 1974 Page 46 1975 Page 50 1976 Page 54 1977 Page 57 1978 Page 60 1979 Page 63 1964 1 AUG The Centre for Advanced Creative Study publishes Signals Newsbulletin, a forum for the discussion of experimental art exhibitions and events. It also includes poetry and essays on science and technology. The group becomes known as Signals London when it moves to premises in Wigmore Street in central London. The gallery closes in 1966. OCT The Labour party wins the general election under the leadership of Harold Wilson. Wilson speaks about the need ‘to think and speak in the language of our scientific age’. 2 1965 3 FEB Arts minister Jennie Lee publishes the first (and only) white paper on the arts – A Policy for the Arts. She argues that the arts must occupy a central place in British life and be part of everyday life for children and adults. She announces a 30% increase to the Arts Council grant. JUL Comprehensive education system replaces grammar and secondary modern schools, aiming to serve all pupils on an equal basis. Between Poetry and Painting Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 22 October – 27 November Curated by Jasia Reichardt Includes: Barry Flanagan, John Latham 4 NOV Indica gallery and bookshop opens at Mason’s Yard, London. -

Bibliographie De La Correspondance De Max Jacob Antonio Rodriguez, Patricia Sustrac

Bibliographie de la correspondance de Max Jacob Antonio Rodriguez, Patricia Sustrac To cite this version: Antonio Rodriguez, Patricia Sustrac. Bibliographie de la correspondance de Max Jacob. Les Cahiers Max Jacob, Association des Amis de Max Jacob (AMJ), 2014, pp.311-325. hal-01806622 HAL Id: hal-01806622 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01806622 Submitted on 9 Jun 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. BIBLIOGRAPHIE DE LA CORRESPONDANCE DE MAX JACOB Antonio RODRIGUEZ et Patricia SUSTRAC ous mentionnons dans cette section les correspondances parues unique- Nment en recueils, incluant celles parues dans Les Cahiers Max Jacob. Les correspondances sont classées par leur titre après l’astérisque si elles sont éditées de manière chronologique ou par ordre alphabétique selon leur destinataire. Lorsque le lieu d’édition est Paris, celui-ci n’a pas été indiqué. Pour les publi- cations parues en revues, se reporter à l’instrument bibliographique : GREEN Maria, Bibliographie et documentation sur Max Jacob, Saint-Étienne : Les Amis de Max Jacob, 1988. Nous indiquons également les correspondances à paraître, les fonds archivistiques contenant des correspondances de Max Jacob appar- tenant à des collections publiques ou privées, ainsi que les principales études consacrées à l’épistolaire de l’auteur. -

N°27 - 2009 Mep Clio 94 20092.Qxd 16/09/09 11:52 Page 2

mep clio 94 20092.qxd 16/09/09 11:52 Page 1 N°27 - 2009 mep clio 94 20092.qxd 16/09/09 11:52 Page 2 Volume publié avec le concours de la Direction Régionale des Affaires Culturelles d’Ile-de-France et du Conseil Général du Val-de-Marne. Clio 94 mep clio 94 20092.qxd 16/09/09 11:52 Page 3 SOMMAIRE PRÉFACE ................................................................................................. P.5 (MICHEL BALARD) LES COURS DE MANDRES .......................................................................... P.7 (JEAN-PIERRE NICOL) MANDRES VUE PAR SES ÉCRIVAINS .......................................................... P.23 (JEAN-PIERRE NICOL) ALFORTVILLE EN TOILE DE FOND (1870-1944) ......................................... P.31 (LOUIS COMBY) MAIRIE, ÉCOLE ET PAUVRETÉ, L’EXEMPLE DU SUD-EST PARISIEN, 1880-1900 .......................................... P.44 (CÉCILE DUVIGNAC-CROISÉ) PAUVRETÉ ET MARGINALITÉ DANS LE SUD-EST PARISIEN (ACTES DU COLLOQUE DE CLIO 94 DU 2 NOVEMBRE 2008) INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... P.59 (GENEVIEVE ARTIGAS-MENANT) TOURISME ET VILLÉGIATURE À ARCUEIL ET EN VALLÉE INFÉRIEURE DE LA BIÈVRE EN AMONT DE PARIS DU XVIE SIECLE AU DÉBUT DU XXIE SIECLE ...............................................P.65 (ROBERT TOUCHET) MAISONS-ALFORT, À TRAVERS L’ÉCRITURE, LA PEINTURE ET LA PHOTOGRAPHIE ......................................................... P.69 (MARCELLE AUBERT) LA ZONE, DE L’UNIVERS LITTÉRAIRE À LA RÉALITÉ HISTORIQUE ............... P.83 (ÉLISE