“Setting Atlanta in Motion”: the Making and Unmaking Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRUID HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT US29 Atlanta Vicinity Fulton County

DRUID HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT HABS GA-2390 US29 GA-2390 Atlanta vicinity Fulton County Georgia PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY DRUID HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT HABS No. GA-2390 Location: Situated between the City of Atlanta, Decatur, and Emory University in the northeast Atlanta metropolitan area, DeKalb County. Present Owner: Multiple ownership. Present Occupant: Multiple occupants. Present Use: Residential, Park and Recreation. Significance: Druid Hills is historically significant primarily in the areas of landscape architecture~ architecture, and conununity planning. Druid Hills is the finest examp1e of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century comprehensive suburban planning and development in the Atlanta metropo 1 i tan area, and one of the finest turn-of-the-century suburbs in the southeastern United States. Druid Hills is more specifically noted because: Cl} it is a major work by the eminent landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted and Ms successors, the Olmsted Brothers, and the only such work in Atlanta; (2) it is a good example of Frederick Law Olmsted 1 s principles and practices regarding suburban development; (3) its overall planning, as conceived by Frederick Law Olmsted and more fully developed by the Olmsted Brothers, is of exceptionally high quality when measured against the prevailing standards for turn-of-the-century suburbs; (4) its landscaping, also designed originally by Frederick Law Olmsted and developed more fully by the Olmsted Brothers, is, like its planning, of exceptionally high quality; (5) its actual development, as carried out oripinally by Joel Hurt's Kirkwood Land Company and later by Asa G. -

Tunnel from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia This Article Is About Underground Passages

Tunnel From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about underground passages. For other uses, see Tunnel (disambiguation). "Underpass" redirects here. For the John Foxx song, see Underpass (song). Entrance to a road tunnel inGuanajuato, Mexico. Utility tunnel for heating pipes between Rigshospitalet and Amagerværket in Copenhagen,Denmark Tunnel on the Taipei Metro inTaiwan Southern portal of the 421 m long (1,381 ft) Chirk canal tunnel A tunnel is an underground or underwater passageway, dug through the surrounding soil/earth/rock and enclosed except for entrance and exit, commonly at each end. A pipeline is not a tunnel, though some recent tunnels have used immersed tube construction techniques rather than traditional tunnel boring methods. A tunnel may be for foot or vehicular road traffic, for rail traffic, or for a canal. The central portions of a rapid transit network are usually in tunnel. Some tunnels are aqueducts to supply water for consumption or for hydroelectric stations or are sewers. Utility tunnels are used for routing steam, chilled water, electrical power or telecommunication cables, as well as connecting buildings for convenient passage of people and equipment. Secret tunnels are built for military purposes, or by civilians for smuggling of weapons, contraband, or people. Special tunnels, such aswildlife crossings, are built to allow wildlife to cross human-made barriers safely. Contents [hide] 1 Terminology 2 History o 2.1 Clay-kicking 3 Geotechnical investigation and design o 3.1 Choice of tunnels vs. -

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

Emory Safety Alliance Members

accreditation 2017 - Emory Emory Safety Alliance Safe America Communities Re A Safe Place to Work, Teach, Study and Live! Toshiba Application prepared by Paris Harper 26 April 2017 Contents Section 1: Contact Information ................................................................................................................... 2 Section 2: Community Description ............................................................................................................. 3 Section 3: Criteria to be a Safe Community ............................................................................................... 4 I. Sustained Collaboration ....................................................................................................................... 4 II. Data collection and application .......................................................................................................... 8 1. Demographic Data ........................................................................................................................... 8 2. Injury and fatality data .................................................................................................................. 10 III-IV. Effective Strategies to Address Unintentional and Intentional Injuries, Evaluation Methods 23 Section 4: Community Inventory .............................................................................................................. 28 Appendix A: Emory Safety Alliance Members ......................................................................................... -

June 2014 [email protected] • Inmanpark.Org • 245 North Highland Avenue NE • Suite 230-401 • Atlanta 30307 Volume 42 • Issue 6

THE Inman Park Advocator Atlanta’s Small Town Downtown News • Newsletter of the Inman Park Neighborhood Association June 2014 [email protected] • inmanpark.org • 245 North Highland Avenue NE • Suite 230-401 • Atlanta 30307 Volume 42 • Issue 6 President’s Message With Gratitude BY DENNIS MOBLEY • [email protected] I know it’s not Thanksgiving, but I wish nonetheless to use this initial President’s Message to express my thanks for a number of things as I embark on my two-year term. First, I wish to thank my friend and predecessor Andy Coffman for the opportunity to retaliate for his portrait in the April issue of the Advocator, showing off all of his Georgia Half Marathon medals. I was in fact by his side every step of the way in all of those races! Second, and on a more serious note, I wish to thank him for believing me capable of following in his presidential footsteps. In fact, I will make every effort to keep him involved so that I and my Board colleagues can benefit from his wisdom and experience during our tenure. Given that this article was written in the aftermath of yet-another successful Inman Park Festival, with glorious and well-deserved sunny weather, I wish to thank the Festival Committee on which I remain, and the more than 900 volunteers who each year help us all pull off a very complicated and wondrous event. Thanks, too, to the vendors, artists, musicians, beer purveyors, and Home Tour families who make this an event that annually attracts people by the tens of thousands from miles around. -

Raise the Curtain

JAN-FEB 2016 THEAtlanta OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE OF AtLANTA CoNVENTI ON &Now VISITORS BUREAU ATLANTA.NET RAISE THE CURTAIN THE NEW YEAR USHERS IN EXCITING NEW ADDITIONS TO SOME OF AtLANTA’S FAVORITE ATTRACTIONS INCLUDING THE WORLDS OF PUPPETRY MUSEUM AT CENTER FOR PUPPETRY ARTS. B ARGAIN BITES SEE PAGE 24 V ALENTINE’S DAY GIFT GUIDE SEE PAGE 32 SOP RTS CENTRAL SEE PAGE 36 ATLANTA’S MUST-SEA ATTRACTION. In 2015, Georgia Aquarium won the TripAdvisor Travelers’ Choice award as the #1 aquarium in the U.S. Don’t miss this amazing attraction while you’re here in Atlanta. For one low price, you’ll see all the exhibits and shows, and you’ll get a special discount when you book online. Plan your visit today at GeorgiaAquarium.org | 404.581.4000 | Georgia Aquarium is a not-for-profit organization, inspiring awareness and conservation of aquatic animals. F ATLANTA JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2016 O CONTENTS en’s museum DR D CHIL ENE OP E Y R NEWL THE 6 CALENDAR 36 SPORTS OF EVENTS SPORTS CENTRAL 14 Our hottest picks for Start the year with NASCAR, January and February’s basketball and more. what’S new events 38 ARC AROUND 11 INSIDER INFO THE PARK AT our Tips, conventions, discounts Centennial Olympic Park on tickets and visitor anchors a walkable ring of ATTRACTIONS information booth locations. some of the city’s best- It’s all here. known attractions. Think you’ve already seen most of the city’s top visitor 12 NEIGHBORHOODS 39 RESOURCE Explore our neighborhoods GUIDE venues? Update your bucket and find the perfect fit for Attractions, restaurants, list with these new and improved your interests, plus special venues, services and events in each ’hood. -

Atlanta's Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class

“To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 by William Seth LaShier B.A. in History, May 2009, St. Mary’s College of Maryland A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Eric Arnesen James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that William Seth LaShier has passed the Final Examinations for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 20, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 William Seth LaShier Dissertation Research Committee Eric Arnesen, James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History, Dissertation Director Erin Chapman, Associate Professor of History and of Women’s Studies, Committee Member Gordon Mantler, Associate Professor of Writing and of History, Committee Member ii Acknowledgements I could not have completed this dissertation without the generous support of teachers, colleagues, archivists, friends, and most importantly family. I want to thank The George Washington University for funding that supported my studies, research, and writing. I gratefully benefited from external research funding from the Southern Labor Archives at Georgia State University and the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Books Library (MARBL) at Emory University. -

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP)

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP) Prepared By: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT JUNE 2015 Page is left blank intentionally for document formatting City of Atlanta 2016‐2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) and Community Work Program (CWP) June 2015 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Office of Planning 55 Trinity Avenue Suite 3350 Atlanta, GA 30303 http://www.atlantaga.gov/indeex.aspx?page=391 Online City Projects Database: http:gis.atlantaga.gov/apps/cityprojects/ Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adreaan Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Mary Norwood Andre Dickens Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development Terri M. Lee, Deputy Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Project Staff Jessica Lavandier, Assistant Director, Strategic Planning Rodney Milton, Principal Planner Lenise Lyons, Urban Planner Capital Improvements Program Sub‐Cabinet Members Atlanta BeltLine, -

The New York City Subway

John Stern, a consultant on the faculty of the not-for-profit Aesthetic Realism Foundation in New York City, and a graduate of Columbia University, has had a lifelong interest in architecture, history, geology, cities, and transportation. He was a senior planner for the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission in New York, and is an Honorary Director of the Shore Line Trolley Museum in Connecticut. His extensive photographs of streetcar systems in dozens of American and Canadian cities during the late 1940s, '50s, and '60s comprise a major portion of the Sprague Library's collection. Mr. Stern resides in New York City with his wife, Faith, who is also a consultant of Aesthetic Realism, the education founded by the American poet and critic Eli Siegel (1902-1978). His public talks include seminars on Fiorello LaGuardia and Robert Moses, and "The Brooklyn Bridge: A Study in Greatness," written with consultant and art historian Carrie Wilson, which was presented at the bridge's 120th anniversary celebration in 2003, and the 125th anniversary in 2008. The paper printed here was given at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, 141 Greene Street in NYC on October 23rd and at the Queens Public Library in Flushing in 2006. The New York Subway: A Century By John Stern THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27, 1904 was a gala day in the City of New York. Six hundred guests assembled inside flag-bedecked City Hall listened to speeches extolling the brand-new subway, New York's first. After the last speech, Mayor George B. McClellan spoke, saying, "Now I, as Mayor, in the name of the people, declare the subway open."1 He and other dignitaries proceeded down into City Hall station for the inau- gural ride up the East Side to Grand Central Terminal, then across 42nd Street to Times Square, and up Broadway to West 145th Street: 9 miles in all (shown by the red lines on the map). -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

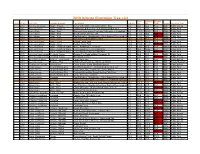

2019 Champion Trees

2019 Atlanta Champion Tree List CIR HEIGHT SPREA Rank YEAR SPECIES COMMON NAME LOCATION CIR (ft) (in) (ft) D (ft) Points Location Type 1 2014 Acer buergerianum Maple - Trident corner of Peachtree Rd and Peachtree Way 2.2 26.0 36.0 18.0 66.5 Public Access 1 2015 Acer japonicum Maple - Japanese Callanwolde Arts Center - in dedication garden area 2.3 27.5 23.2 22.5 56.3 Public Park 1 2011 Acer rubrum Maple - Red McLendon Ave, across from Lake Claire park on boardwalk 9.2 110.0 109.3 52.5 232.5 Public Park 2 2012 Acer rubrum Maple - Red Dearborn Park, Decatur, GA 9.5 114.5 95.2 50.0 222.2 Public Park 3 2010 Acer rubrum Maple - Red East Palisades, Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area8.5 101.5 88.0 45.0 200.8 Public Park 1 2002 Acer saccharinum Maple - Silver 310 Robinhood Rd Atlanta 30309 14.9 178.8 85.0 95.0 287.6 Private Residence 1 2010 Acer saccharinum Maple - Silver Herbert Taylor Park 13.7 164.0 101.6 91.0 288.4 Public Park 1 2012 Acer saccharinum Maple - Silver Herbert Taylor Park 12.6 151.0 111.0 60.0 277.0 Public Park 1 2014 Acer saccharum Maple - Southern Sugar 207 E. Parkwood, Decatur, GA 10.9 131.0 81.8 70.0 230.3 Private Residence 2 2010 Acer saccharum Maple - Southern Sugar Lionel Hampton- Beecher Hills Park 8.0 96.0 104.3 52.0 213.3 Public Park 2 2012 Acer saccharum Maple - Southern Sugar Lionel Hampton- Beecher Hills Park 6.2 74.0 119.4 50.0 205.9 Public Park 1 2010 Aesculus hippocastanumChestnut - Horse Decatur City Parks building, Sycamore St.