Portsmouth, NH, Early Brick Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allington Saved

Autumn 2005 Your Number One REGULAR Newsletter Editor : Cllr David Goodall No.102 Allington Saved Your Local Garage for Servicing & repairs MOTs arranged Vehicle tuning AT COMPETITIVE PRICING Tel: 023 8047 4553 __________ Car Sales Carol Boulton & Chris Huhne with one pleased Allington resident Good selection In this Issue Cllr Carol Boulton reports: The recently published All Sales Cars Serviced planning inspector’s report into the Eastleigh Borough and Warranted by us ———— Council Local Plan has backed the Liberal Democrat Photo Action Part Exchange File controlled council plans NOT to have major development ———— area consisting of 4000 houses up Allington Lane. Licensed Credit Broker Green Power The smaller Borough Council made a brave decision to ———— ignore the advice of the structural planning authority the Tories Cut Tel: 023 8047 6481 County Council, for a major development area south east Bus Services __________ ———— of Eastleigh and the planning inspector has fully backed Lib Dem the decision. nitebus service The decision will mean the required houses for the area 34 HIGH STREET extended will mainly be built on brownfield sites within the urban ———— WEST END New Hospital edge of existing towns and villages across the Borough. Taxi Service Most of these will be within Eastleigh itself on sites like SOUTHAMPTON ———— the old Pirelli works. SO30 3DR Policy Point: This is a great decision for West End and naturally, as an Council Tax Allington Lane resident myself, I am very pleased that Revaluation this particular battle has finally been won. I and my ———— Liberal Democrat colleagues will continue to be on our Europe Spot: guard against any such uncontrolled development in the www.newchapelcars.co.uk New MEP countryside. -

Hampshire Top Ten Things You Never Knew

Ten things you never knew about Hampshire Famous for any number of reasons, Hampshire is also regarded as the birthplace of modern fly-fishing, wind-surfing and bird-watching. But here’s our list of Top 10 Things You Never Knew about the county… 1. Winchester - once King Alfred’s capital, and the venue for the marriage of Queen Mary I to King Philip II of Spain – has been crowned the best place to live in Britain by The Sunday Times. The cathedral city inspired John Keats to write his famous Ode To Autumn in 1819. Today, the ancient capital includes restaurants such as Chesil Rectory and Michelin-starred Black Rat. 2. Leckford Estate in the Test Valley was purchased by John Spedan Lewis in 1929, and has been farmed for over 87 years. Home to The Waitrose Farm, it’s a place where visitors will find a fabulous farm shop, café, a garden nursery in nearby Longstock, and see one of the finest water gardens in the world. Leckford village itself comprises around 40 houses and cottages, which are occupied by present or retired employees of the John Lewis Partnership, and are painted in the partnership colours of green and white. 3. 2017 will see the county mark the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen. Less well-known is the fact that 50 years later, Sweet Fanny Adams was brutally murdered by solicitor's clerk Frederick Baker in nearby Alton. A couple of years later, new rations of tinned mutton - introduced to sailors in Portsmouth - failed to impress the seamen, who suggested it might even be the butchered remains of poor Fanny Adams. -

HISTORIC RESOURCES CHAPTER 2015 REGIONAL MASTER PLAN for the Rockingham Planning Commission Region

HISTORIC RESOURCES CHAPTER 2015 REGIONAL MASTER PLAN For the Rockingham Planning Commission Region Rockingham Planning Commission Regional Master Plan Historical Resources C ONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 What the Region Said About Historical Resources ............................................................................ 2 Historical Resources Goals ............................................................................................................... 3 Existing Conditions ........................................................................................................................... 5 Historical Background and Resources in the RPC Region....................................................................... 5 Preservation Tools .......................................................................................................................... 9 Key Issues and Challenges ............................................................................................................. 18 What Do We Preserve? ................................................................................................................. 18 Education and Awareness .............................................................................................................. 19 Redevelopment, Densification, and Tear-Downs ................................................................................ 20 -

Meet the Hampshire, Southampton, and Isle of Wight Complex Care Team

Meet the Hampshire, Southampton, and Isle of Wight Complex Care team Our team consists of both clinical and operational staff who are responsible for commissioning the care provision for children and young people eligible for NHS continuing care up to the age of 18. We operate across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, excluding Portsmouth. Currently we are overseeing the care for approx. 116 children and their families across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. It is important to us that the supported children and their families receive the best possible care. In the coming weeks we are hoping to engage with children and their families in our care to fully understand the barriers that they face with the service they received from us and any other services which are being provided. We are aware our families face issues and challenges around the care provided by our Care Providers, Direct Payments and employment of their own PA’s. Hampshire Parent Network and Parent Voice have generously offered to host a meet and greet session to look at the pressures families face on a day-to-day basis. This will help us try to address some of these issues which are within our remit. Our aim is that these meetings will continue on a regular basis so that we can build a relationship with families and better understand any issues faced from a family perspective. We have also commenced a co-production group which families can join for specific topics or on an ongoing basis. Our initial meeting will be held on Zoom on Monday 28 June, 11-12pm - here is the link Zoom meeting details: Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81922934944?pwd=OXl3c2lYeFpKOFJveWlBOU1qYy9hQT09 Meeting ID: 819 2293 4944 Passcode: NHS The initial meeting will not have a set agenda, as we would just like to get to know our families issues first. -

![Lco~[), Nrev~ Lham~Sfn~[E ]977 SUPREME COURT of NEW HAMPSHIRE Appoi Nted](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9794/lco-nrev-lham-sfn-e-977-supreme-court-of-new-hampshire-appoi-nted-1049794.webp)

Lco~[), Nrev~ Lham~Sfn~[E ]977 SUPREME COURT of NEW HAMPSHIRE Appoi Nted

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. 6~N ~~~~'L~©DUCu~©u~ U(Q ll~HE ~£~"~rr»~~h\~lE (ot1l~u g~ U\]~V~ li"~A[~rr~s.~~Du 8 1.\ COU\!lCO~[), NrEV~ lHAM~Sfn~[E ]977 SUPREME COURT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Appoi nted_ Frank R. Kenison, Chief Justice Apri 1 29, 1952 Edward J. Lampron, Senior Justice October 5, 1949 William A. Grimes, Associate Justice December 12, 1966 Maurice P. Bois, Associate Justice October 5, 1976 Charles G. Douglas, III, Associate Justice January 1, 1977 George S. Pappagianis Clerk of Supreme Court Reporter of Decisions li:IDdSlWi&iImlm"'_IIIII'I..a_IIIHI_sm:r.!!!IIIl!!!!__ g~_~= _________ t.':"':iIr_. ____________ .~ • • FE~l 2 ~: 1978 J\UBttst,1977 £AU • "1 be1.J..e.ve. tha..:t oWl. c.oWtt hM pWl-Oue.d a. -6te.a.dy c.OWl-Oe. tfvtoughoL1;t the. ye.aJlA, tha..:t U ha.6 pll.ogll.u-6e.d . a.nd a.ppUe.d the. pJUnuplu 06 OUll. law-6 -Ln a. ma.nne.ll. c.o Y!.-6-L-6te.r"t wUh the. pubUc. iMe.Il.Ut a.nd that aU the. jud-LuaJty w-L.U c..oJ1-ti.nue. to be, a. -6a.6e.guaJtd to the. .V,b eJr.;t,[u, 1l.e..6 po MibiJ!ft[u a.nd d-Lg nUy we. c.heJLU h. " Honorable Frank R. Kenison, Chief Justice, Supreme Court of New Hampshire, liThe State of the Judiciary,1I 3 MAR 77 House Record, page 501. -

History of Portsmouth NH for Children-Revised

History of Portsmouth NH for Children-Revised People, Places, and Events 1603 1800 1600 1700 1800 Printed Spring, 2005 Revised Summer, 2011 2 Dedicated to the former, current, and future third graders at Dondero School, Portsmouth, NH Printed Spring, 2005 Revised Summer, 2011 © Mrs. Bodwell, Mrs. Hinton, Mrs. George Special thank you to: Jerrianne Boggis and Valerie Cunningham 3 Table of Contents In the Beginning.................................................. .............4, 5 Others Followed...............................................................6, 7 Strawbery Banke.............................................................8, 9 Slave Trade...................................................................10, 11, 12 Early Portsmouth.........................................................13, 14, 15 Jackson House............................................................ ....16, 17 Indian Conflict…..........................................................1 8, 19, 20 Warner House.................................................................21, 22 Prince Whipple..............................................................23, 24, 25 Moffat-Ladd..................................................................26, 27 Chase House...................................................................28, 29 Pitt Tavern.....................................................................30, 31 John Paul Jones...........................................................32, 33, 34 Langdon House.............................................................35, -

Media and Press Contacts

Media and Press Contacts Television BBC South East Today Covers East and West Sussex, Surrey and Kent Website: www.bbc.co.uk/southeasttoday Tel: 01892 675580 (Newsroom) Address: BBC South East Today, The Great Hall, Mount Pleasant Road, Tunbridge Wells TN1 1QQ Meridian Broadcasting (ITV) Website: www.itv.com/meridian-east Tel: 0844 881 4353 Address: Olivier House 18 Marine Parade, Brighton BN2 1TL Radio BBC Surrey BBC local radio for Surrey and NE Hampshire. Much of its programming is shared with BBC Sussex. Website: bbc.co.uk/surrey Tel: Main switchboard: 01483 306306 On-air - call a show: 0370 411 1046 News desk Email: [email protected] Surrey News Editor: Mark Carter Email: [email protected] Fax: 01483 304952 Surrey Breakfast Show Producer: Jack Fiehn Email: [email protected] Address: BBC Surrey, Broadcasting Centre, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7AP Newspapers Get Surrey Web Team Address: Stoke Mill, Woking road, Guildford GU1 1QA Online Editor: Stuart Richards [email protected] Telephone: 01483 508914 Online Reporter: Amy De-Keyzer [email protected] (East Surrey) Surrey Advertiser/Woking Advertiser/Surrey Herald/Staines News/Surrey Times/Informer Series Address: Stoke Mill, Woking road, Guildford GU1 1QA News Editor Tony Green [email protected] (Surrey Advertiser, Surrey Times) News Editor Beth Duffell [email protected] (Surrey Advertiser 01483 508858 Elmbridge, Woking Advertiser, Woking Informer) News Editor Amy Taylor [email protected] (Herald & News, Staines -

Chapter 2 Formative Influences

Chapter- 2 Formative Influences South Downs: Landscape Character Assessment October 2020 Chapter 2 Formative Influences Physical Influences Geology and Topography 2.1 The South Downs is dominated by a spine of Chalk that stretches from Winchester in the west to the cliffs of Beachy Head in the east. To the north of the Chalk the older sandy rocks of the Lower Greensand and soft shales of the Wealden Clays are exposed. The Chalk is separated from the Lower Greensand by a belt of low-lying ground marked by the Gault and a ‘terrace’ of Upper Greensand that lies at the foot of the Chalk scarp. To the south of the chalk the younger Tertiary rocks overlie the Chalk. The solid geology within in South Downs National Park can be viewed on the South Downs National Park LCA online map. The different rock formations are considered in chronological order below. The description includes the development of each rock formation, its composition, and its influence on the topography and character of the South Downs. A topographical map is also available on the LCA online map. Cretaceous rocks Wealden Series 2.2 The oldest rocks in the South Downs are those of the low lying clays of the Wealden Series that are exposed along the northern boundary of the study area. During the early part of the Cretaceous period, some 140 million years ago, a lake covered the area and it was during this time that the Wealden Clay was laid down. It consists of shales and mudstones with outcrops of siltstones, sandstones, shelly limestones and clay ironstones. -

Few Americans in the 1790S Would Have Predicted That the Subject Of

AMERICAN NAVAL POLICY IN AN AGE OF ATLANTIC WARFARE: A CONSENSUS BROKEN AND REFORGED, 1783-1816 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jeffrey J. Seiken, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor John Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Margaret Newell _______________________ Professor Mark Grimsley Advisor History Graduate Program ABSTRACT In the 1780s, there was broad agreement among American revolutionaries like Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton about the need for a strong national navy. This consensus, however, collapsed as a result of the partisan strife of the 1790s. The Federalist Party embraced the strategic rationale laid out by naval boosters in the previous decade, namely that only a powerful, seagoing battle fleet offered a viable means of defending the nation's vulnerable ports and harbors. Federalists also believed a navy was necessary to protect America's burgeoning trade with overseas markets. Republicans did not dispute the desirability of the Federalist goals, but they disagreed sharply with their political opponents about the wisdom of depending on a navy to achieve these ends. In place of a navy, the Republicans with Jefferson and Madison at the lead championed an altogether different prescription for national security and commercial growth: economic coercion. The Federalists won most of the legislative confrontations of the 1790s. But their very success contributed to the party's decisive defeat in the election of 1800 and the abandonment of their plans to create a strong blue water navy. -

Eastleigh Borough Council and Parishes (Hampshire)

Case study on service delegations to local (parish and town) councils EASTLEIGH BOROUGH COUNCIL AND PARISHES (HAMPSHIRE) This is an example of service delegation being undertaken across a whole Borough, namely Eastleigh in Hampshire and its ten local parish and town councils. Eastleigh Borough Council has been forward looking in its approach to delegations and it actively encourages local councils to explore the benefits of delivering services more locally to citizens. Context "The welfare of the people is the most important law is the motto of Eastleigh Borough Council. The current Borough was formed in 1974, when the then Borough of Eastleigh was expanded to include part of Winchester Rural District. Since 1994 it has a policy of encouraging the formation of new parishes. The Borough now consists of ten parishes – the oldest set up in 1894 and the two newest, Chadlers Ford and Allbrook, created in April 2010 – plus the town of Eastleigh which remains unparished. Eastleigh District Association of Local Councils (EDALC) has been established and it works with the Hampshire Association of Local Councils to support the parishes. The Chairman of EDALC, believes that The elatioship etee us [the parishes] and the Borough is much better in Eastleigh than other parts of Hapshie, ad oe the hole out. The Chief Executive of the Hampshire Association of Local Councils also believes Eastleigh has an excellent and collaborative approach to service delegation: This comes at a time when in other areas of the country relatively few local councils have taken on delivery of delegated services and a number of [principal] local authorities are cautious about delegatig otol do a tie. -

1. Name of Property Historic Name Margeson, Richman, Estate Other Names/Site Number Hawkridge, Edwin, Estate; Loomis, Ralph, Estate

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior i r National Park Service 01990' National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Margeson, Richman, Estate other names/site number Hawkridge, Edwin, Estate; Loomis, Ralph, Estate 2. Location street & number Long Point Road N/A I I not for publication city, town Newington (Pease Air Force Base) N/A I I vicinity" state New Hampshire code NH county Rockingham code 015 zip code 03801 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property private 1 1 building(s) Contributing Noncontributing public-local [x"| district 2 ____buildings I public-State site ____ sites [xl public-Federal structure 1 structures 1 object ____ objects 1 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A listed in the National Register ____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this IS! nomination ED request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

H. Doc. 108-222

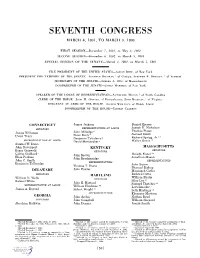

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802.