ANOUILH's USE of Mytrlological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Case Study: Multiverse Wireless DMX at Hadestown on Broadway

CASE STUDY: Multiverse Wireless DMX Jewelle Blackman, Kay Trinidad, and Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer in Hadestown (Matthew Murphy) PROJECT SNAPSHOT Project Name: Hadestown on Broadway Location: Walter Kerr Theatre, NY, NY Hadestown is an exciting Opening Night: April 17, 2019 new Broadway musical Scenic Design: Rachel Hauck (Tony Award) that takes the audience Lighting Design: Bradley King (Tony Award) on a journey to Hell Associate/Assistant LD: John Viesta, Alex Mannix and back. Winner of eight 2019 Tony Awards, the show Lighting Programmer: Bridget Chervenka Production Electrician: James Maloney, Jr. presents the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice set to its very Associate PE: Justin Freeman own distinctive blues stomp in the setting of a low-down Head Electrician: Patrick Medlock-Turek New Orleans juke joint. For more information, read the House Electrician: Vincent Valvo Hadestown Review in Lighting & Sound America. Follow Spot Operators: Paul Valvo, Mitchell Ker Lighting Package: Christie Lites City Theatrical Solutions: Multiverse® 900MHz/2.4GHz Transmitter (5910), QolorFLEX® 2x0.9A 2.4GHz Multiverse Dimmers (5716), QolorFLEX SHoW DMX Neo® 2x5A Dimmers, DMXcat® CHALLENGES SOLUTION One of the biggest challenges for shows in Midtown Manhattan City Theatrical’s Multiverse Transmitter operating in the 900MHz looking to use wireless DMX is the crowded spectrum. With every band was selected to meet this challenge. The Multiverse lighting cue on stage being mission critical, a wireless DMX system – Transmitter provided DMX data to battery powered headlamps. especially one requiring a wide range of use, compatibility with other A Multiverse Node used as a transmitter and operating on a wireless and dimming control systems, and size restraints – needs SHoW DMX Neo SHoW ID also broadcast to QolorFlex Dimmers to work despite its high traffic surroundings. -

Stepping out of the Frame Alternative Realities in Rushdie’S the Ground Beneath Her Feet

Universiteit Gent 2007 Stepping Out of the Frame Alternative Realities in Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet Verhandeling voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte voor het verkrijgen van de graad van Prof. Gert Buelens Licentiaat in de taal- en letterkunde: Prof. Stef Craps Germaanse talen door Elke Behiels 1 Preface.................................................................................................................. 3 2 Historical Background: the (De-)Colonization Process in India.......................... 6 2.1 The Rise of the Mughal Empire................................................................... 6 2.2 Infiltration and Colonisation of India: the Raj ............................................. 8 2.3 India, the Nation-in-the-making and Independence (1947) ....................... 11 2.3.1 The Rise of Nationalism in India ....................................................... 11 2.3.2 Partition and Independence................................................................ 12 2.3.3 The Early Postcolonial Years: Nehru and Indira Gandhi................... 13 2.4 Contemporary India: Remnants of the British Presence............................ 15 3 Postcolonial Discourse: A (De)Construction of ‘the Other’.............................. 19 3.1 Imperialism – Colonialism – Post-colonialism – Globalization ................ 19 3.2 Defining the West and Orientalism............................................................ 23 3.3 Subaltern Studies: the Need for a New Perspective.................................. -

Jerold Frederic Presents Concert of Gripping Music Philharmonic

THE% ECHO VOL. XXV TAYLOR UNIVERSITY, UPLAND, INDIANA, SATURDAY. FEBRUARY 5, 1938 NO. 9 Judge Fred Bale Jerold Frederic Mystery Abounds Philharmonic Orchestra Coming Discusses Vital Presents Concert When Dramatists Issues at T. U. Of Gripping Music Thrill Audience All Taylor music lovers were A phantom tiger, a death light, thrilled at the masterful playing a haunted house, a terrific storm of Jehold Frederic as he was pre — an ideal setting for a mystery! sented by the Lyceum Committee, In Spiers Hall on January 29th Tuesday evening, January 18th, one of the hit programs of the in Shreiner Auditorium. year was the presentation of His graduation from the "Tiger House", Robert St. Clair's thundering londs to the soft, popular three act. novel comedy. sweet passages, his brilliant tech In the minds of the audience nique, excellent tone quality and which crowded the little audi keen sense of rhythm held the torium to its capacity, the play audience enthralled during the | ranks high among Taylor's Magic of Murdock G. H. Shapiro and entire program. His powerful, literary productions. No one was His Orchestra to yet gentle fingers brought forth disappointed in the thrilling en Provides Thrills his notable creative ability in his tertainment. Appear at Taylor interpretation of Chopin. His Weird fantastical sounds, For Large Group presentation of Liszt himself, tricky movable panels, cruel On February 19, the Lyceum rather than his music, it was as | clutching claws! Was it any Even the "front" seats of Committee is presenting the next if his listeners were for the time wonder onlookers sat on the Shreiner Auditorium were oc in the series of programs. -

Classics 3: Program Notes Overture to Candide Leonard Bernstein Born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, August 25, 1918

Classics 3: Program Notes Overture to Candide Leonard Bernstein Born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, August 25, 1918; died in New York, October 14, 1990 After collaborating on The Lark, a play with incidental music about Joan of Arc, Leonard Bernstein and Lillian Hellman turned their attention in 1954 to Voltaire’s novella Candide. They thought it the perfect vehicle to make an artistic statement against political intolerance in American society, just as Voltaire had done in eighteenth-century France. After bringing in poet Richard Wilbur to write the lyrics, they worked intermittently on Candide for two years. Enormous amounts of money were spent on the production, which opened in Boston on October 29, 1956. Though many critics called it brilliant, the production failed financially; after moving to New York in December, it was shut down after just seventy-three performances. Everyone had someone to blame, but many thought it failed because of audience confusion about its hybrid nature—was it an opera, operetta, or a musical? Leonard Bernstein: celebrating his The story revolves around the illegitimate Candide, who centennial loves and is loved in return by Cunegonde, daughter of nobility. They are plagued by myriad disasters, which lead them from Westphalia to Lisbon, Paris, Cadiz, Buenos Aires, Eldorado, Surinam, and finally Venice, where they are united at last. Bernstein’s often witty, sometimes tender music has been considered the work’s greatest asset, both in the initial failed production and in later successful versions. The Overture, possibly Bernstein’s most frequently performed piece, perfectly captures the mockery and satire as well as the occasional introspective moment of Voltaire’s masterful creation. -

Surviving Antigone: Anouilh, Adaptation, and the Archive

SURVIVING ANTIGONE: ANOUILH, ADAPTATION AND THE ARCHIVE Katelyn J. Buis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Cynthia Baron, Advisor Jonathan Chambers ii ABSTRACT Dr. Cynthia Baron, Advisor The myth of Antigone has been established as a preeminent one in political and philosophical debate. One incarnation of the myth is of particular interest here. Jean Anouilh’s Antigone opened in Paris, 1944. A political and then philosophical debate immediately arose in response to the show. Anouilh’s Antigone remains a well-known play, yet few people know about its controversial history or the significance of its translation into English immediately after the war. It is this history and adaptation of Anouilh’s contested Antigone that defines my inquiry. I intend to reopen interpretive discourse about this play by exploring its origins, its journey, and the archival limitations and motivations controlling its legacy and reception to this day. By creating a space in which multiple readings of this play can exist, I consider adaptation studies and archival theory and practice in the form of theatre history, with a view to dismantle some of the misconceptions this play has experienced for over sixty years. This is an investigation into the survival of Anouilh’s Antigone since its premiere in 1944. I begin with a brief overview of the original performance of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone and the significant political controversy it caused. The second chapter centers on the changing reception of Anouilh’s Antigone beginning with the liberation of Paris to its premiere on the Broadway stage the following year. -

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

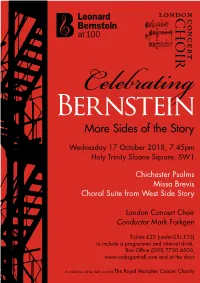

Bernsteincelebrating More Sides of the Story

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door A collection will be held in aid of The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Music Director: include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all Mark Forkgen ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut Nathan Mercieca from the score of the musical. countertenor In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in Richard Pearce medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for organ The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, countertenor soloist and percussion. Anneke Hodnett harp After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Sacha Johnson and West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, Alistair Marshallsay America and Somewhere. -

ARSC Journal

LEONARD BERNSTEIN, A COMPOSER DISCOGRAPHY" Compiled by J. F. Weber Sonata for clarinet and piano (1941-42; first performed 4-21-42) David Oppenheim, Leonard Bernstein (recorded 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, 3ss.) Herbert Tichman, Ruth Budnevich (rec. c.1953} Concert Hall Limited Editions H 18 William Willett, James Staples (timing, 9:35) Mark MRS 32638 (released 12-70, Schwann) Stanley Drucker, Leonid Hambro (rec. 4-70) (10:54) Odyssey Y 30492 (rel. 5-71) (7) Anniversaries (for piano) (1942-43) (2,5,7) Leonard Bernstein (o.v.) (rec. 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, ls.) (1,2,3) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (4:57) (78: RCA Victor 12 0683 in set DM 1278, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58) (4,5) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (3:32) (78: RCA Victor 12 0228 in set DM 1209, ls.) (vinyl 78: RCA Victor 18 0114 in set DV 15, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 (6,7) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (2:18) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 Jeremiah symphony (1941-44; f.p. 1-28-44) Nan Merriman, St. Louis SO--Leonard Bernstein (rec. 12-1-45) ( 23: 30) (78: RCA Victor 11 8971-3 in set DM 1026, 6ss.) Camden CAL 196 (rel. 2-55, del. 6-60) "Single songs from tpe Broadway shows and arrangements for band, piano, etc., are omitted. Thanks to Jane Friedmann, CBS; Peter Dellheim, RCA; Paul de Rueck, Amberson Productions; George Sponhaltz, Capitol; James Smart, Library of Congress; Richard Warren, Jr., Yael Historical Sound Recordings; Derek Lewis, BBC. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

Orfeo Euridice

ORFEO EURIDICE NOVEMBER 14,17,20,22(M), 2OO9 Opera Guide - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS What to Expect at the Opera ..............................................................................................................3 Cast of Characters / Synopsis ..............................................................................................................4 Meet the Composer .............................................................................................................................6 Gluck’s Opera Reform ..........................................................................................................................7 Meet the Conductor .............................................................................................................................9 Meet the Director .................................................................................................................................9 Meet the Cast .......................................................................................................................................10 The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice ....................................................................................................12 OPERA: Then and Now ........................................................................................................................13 Operatic Voices .....................................................................................................................................17 Suggested Classroom Activities -

JEAN ANOUILH the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Tru St

, .. ., ...I I I 1 • ,,~- • i' JEAN ANOUILH The Australian Elizabethan Theatre Tru st when you fly with Trans-AustraliaAirlines PAT RON : H ER MAJESTY T H E QUEE N P RE SIDE T The Rt. H on . Sir John Latham, G.C.M.G., Q .C. CH AIRM A1 Dr. H . C. Coombs EXECUTIVE Dffi ECTOR Hu gh Hunt HO . SECRETARY :l,faurire Parker STATE REPRESE , TAT JVES: , ew South \,Vales Mr. C. J. A. lvloscs, C.B .E. Qu eensland Prof esso r F. J . Schone II Western Australia Pr ofessor F. Alexander Victoria Mr . A . H. L. Gibson Sou tit Australia Mr. L. C. Waterm an Tasmania Mr . G. F. Davies In presenting TIME REMEMBERED , we are paying tribute to a dramatist whose contribution to the contemporary theatre scene is a11 outstanding one and whose influence has been most strongly felt during the post-war years in Europe. The J1lays of Jean An ouilh have not been widely produced in Cao raln and First Officer at the co mrol s of a TA A Viscount . Australia , and his masterly qualities as a playwright are not TAA pilots are well experi years of flying the length and sufficiently k11011·n. enced and maintain a high breadth of Australia. standard of efficiency in flying TAA 's Airmanship is the total TIME REME1vlBERED htippily contains some of the the nation's finest fleet of skill of many people-in the most typical aspects of his work . .. a sense of the comic, modern aircraft. air and on the ground-w ork ing toward s a common goal: almost biza1'1'e,and tl haunting nostalgia which together pro When you and your family fly your safety, satisfaction and T AA, you get with your ticket peace of mind.