In-Depth Paper About Doh (PDF of 1.84

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adopting Encrypted DNS in Enterprise Environments

National Security Agency | Cybersecurity Information Adopting Encrypted DNS in Enterprise Environments Executive summary Use of the Internet relies on translating domain names (like “nsa.gov”) to Internet Protocol addresses. This is the job of the Domain Name System (DNS). In the past, DNS lookups were generally unencrypted, since they have to be handled by the network to direct traffic to the right locations. DNS over Hypertext Transfer Protocol over Transport Layer Security (HTTPS), often referred to as DNS over HTTPS (DoH), encrypts DNS requests by using HTTPS to provide privacy, integrity, and “last mile” source authentication with a client’s DNS resolver. It is useful to prevent eavesdropping and manipulation of DNS traffic. While DoH can help protect the privacy of DNS requests and the integrity of responses, enterprises that use DoH will lose some of the control needed to govern DNS usage within their networks unless they allow only their chosen DoH resolver to be used. Enterprise DNS controls can prevent numerous threat techniques used by cyber threat actors for initial access, command and control, and exfiltration. Using DoH with external resolvers can be good for home or mobile users and networks that do not use DNS security controls. For enterprise networks, however, NSA recommends using only designated enterprise DNS resolvers in order to properly leverage essential enterprise cybersecurity defenses, facilitate access to local network resources, and protect internal network information. The enterprise DNS resolver may be either an enterprise-operated DNS server or an externally hosted service. Either way, the enterprise resolver should support encrypted DNS requests, such as DoH, for local privacy and integrity protections, but all other encrypted DNS resolvers should be disabled and blocked. -

Technical Impacts of DNS Privacy and Security on Network Service Scenarios

- Technical Impacts of DNS Privacy and Security on Network Service Scenarios ATIS-I-0000079 | April 2020 Abstract The domain name system (DNS) is a key network function used to resolve domain names (e.g., atis.org) into routable addresses and other data. Most DNS signalling today is sent using protocols that do not support security provisions (e.g., cryptographic confidentiality protection and integrity protection). This may create privacy and security risks for users due to on-path nodes being able to read or modify DNS signalling. In response to these concerns, particularly for DNS privacy, new protocols have been specified that implement cryptographic DNS security. Support for these protocols is being rapidly introduced in client software (particularly web browsers) and in some DNS servers. The implementation of DNS security protocols can have a range of positive benefits, but it can also conflict with important network services that are currently widely implemented based on DNS. These services include techniques to mitigate malware and to fulfill legal obligations placed on network operators. This report describes the technical impacts of DNS security protocols in a range of network scenarios. This analysis is used to derive recommendations for deploying DNS security protocols and for further industry collaboration. The aim of these recommendations is to maximize the benefits of DNS security support while reducing problem areas. Foreword As a leading technology and solutions development organization, the Alliance for Telecommunications Industry Solutions (ATIS) brings together the top global ICT companies to advance the industry’s business priorities. ATIS’ 150 member companies are currently working to address network reliability, 5G, robocall mitigation, smart cities, artificial intelligence-enabled networks, distributed ledger/blockchain technology, cybersecurity, IoT, emergency services, quality of service, billing support, operations and much more. -

Ikev2 Configuration for Encrypted DNS

IKEv2 Configuration for Encrypted DNS draft-btw-add-ipsecme-ike Mohamed Boucadair (Orange) Tirumaleswar Reddy (McAfee, Inc.) Dan Wing (Citrix Systems, Inc.) Valery Smyslov (ELVIS-PLUS) July 2020, IETF#108 Agenda • Context • A Sample Use Case • IKE Configuration Attribute for Encrypted DNS • Next Steps 2 Problem Description • Several schemes to encrypt DNS have been specified – DNS over TLS (RFC 7858) – DNS over DTLS (RFC 8094) – DNS over HTTPS (RFC 8484) • …And others are being specified: – DNS over QUIC (draft-ietf-dprive-dnsoquic) • How to securely provision clients to use Encrypted DNS? This use can be within or outside the IPsec tunnel 3 A Sample Use Case: DNS Offload • VPN service providers can offer publicly accessible Encrypted DNS – the split-tunnel VPN configuration allows the client to access the DoH/DoT servers hosted by the VPN provider without traversing the tunnel 4 A Sample Use Case: Protecting Internal DNS Traffic • DoH/DoT ensures DNS traffic is not susceptible to internal attacks – see draft-arkko-farrell-arch-model-t-03#section-3.2.1 • encrypted DNS can benefit to Roaming Enterprise users to enhance privacy – With DoH/DoT the visibility of DNS traffic is limited to only the parties authorized to act on the traffic (“Zero Trust Architecture”) 5 Using IKE to Configure Encrypted DNS on Clients • New configuration attribute INTERNAL_ENC_DNS is defined to convey encrypted DNS information to clients: – Encrypted DNS type (e.g., DoH/DoT) – Scope of encrypted DNS use – One or more encrypted DNS server IPv6 addresses • For IPv4 -

Paper, We Note That Work Is with Help from Volunteer OONI Probe Users

Measuring DoT/DoH Blocking Using OONI Probe: a Preliminary Study Simone Basso Open Observatory of Network Interference [email protected] Abstract—We designed DNSCheck, an active network exper- delivery networks (CDN). This fact raises concerns regarding iment to detect the blocking of DoT/DoH services. We imple- performance [25], competition, and privacy [14]. mented DNSCheck into OONI Probe, the network-interference (While DoH’s centralization and the resulting privacy con- measurement tool we develop since 2012. We compiled a list of popular DoT/DoH services and ran DNSCheck measurements cerns are not the focus of this paper, we note that work is with help from volunteer OONI Probe users. We present pre- underway to mitigate them [38] [24].) liminary results from measurements in Kazakhstan (AS48716), Simultaneously, the rollout of DoT and DoH does not Iran (AS197207), and China (AS45090). We tested 123 DoT/DoH fully solve the surveillance and censorship issues posed by services, corresponding to 461 TCP/QUIC endpoints. We found a cleartext internet. There are at least two remaining fields endpoints to fail or succeed consistently. In AS197207 (Iran), 50% of the DoT endpoints seem blocked. Otherwise, we found that could reveal the precise target of otherwise encrypted that more than 80% of the tested endpoints were always reach- communications. They are the Server Name Indication [19] able. The most frequently blocked services are Cloudflare’s and (SNI) extension inside the TLS ClientHello and the destination Google’s. In most cases, attempting to reach blocked endpoints IP address. However, in a landscape increasingly dominated by failed with a timeout. -

A Cybersecurity Terminarch: Use It Before We Lose It

SYSTEMS ATTACKS AND DEFENSES Editors: Davide Balzarotti, [email protected] | William Enck, [email protected] | Samuel King, [email protected] | Angelos Stavrou, [email protected] A Cybersecurity Terminarch: Use It Before We Lose It Eric Osterweil | George Mason University term · in · arch e /’ t re m , närk/ noun an individual that is the last of its species or subspecies. Once the terminarch dies, the species becomes extinct. hy can’t we send encrypt- in the Internet have a long history W ed email (secure, private of failure. correspondence that even our mail To date, there has only been one providers can’t read)? Why do our success story, and, fortunately, it is health-care providers require us to still operating. Today, almost ev- use secure portals to correspond erything we do online begins with a with us instead of directly emailing query to a single-rooted hierarchical us? Why are messaging apps the global database, whose namespace only way to send encrypted messag- is collision-free, and which we have es directly to friends, and why can’t relied on for more than 30 years: we send private messages without the Domain Name System (DNS). user-facing) layer(s). This has left the agreeing to using a single platform Moreover, although the DNS pro- potential to extend DNSSEC’s verifi- (WhatsApp, Signal, and so on)? Our tocol did not initially have verifica- cation protections largely untapped. cybersecurity tools have not evolved tion protections, it does now: the Moreover, the model we are using to offer these services, but why? DNS Security Extensions (DNS- exposes systemic vulnerabilities. -

Encrypting Network Traffic

Network Security Encrypting Network Communication Radboud University, The Netherlands Spring 2019 Acknowledgement Slides (in particular pictures) are based on lecture slides by Ruben Niederhagen (http://polycephaly.org) Network Security – Encrypting Network Communication2 A short recap I Hostname resolution in the Internet uses DNS I Two kinds of servers: authoritative and caching I Two kinds of requests: iterative and recursive I DNS tunneling: I Encode (SSH) traffic in DNS requests to authoritative server I Special authoritative server extracts and handles SSH data I DNS DDOS amplification: I Send DNS request with spoofed target IP address I Much larger reply launched onto target I DNS spoofing/cache poisoning: provide wrong DNS data I Blind spoofing: cannot see (but trigger) request I Countermeasure against blind spoofing: randomization I Most powerful attack: sniffing DNS spoofing I Countermeasures: Use crypto to protect DNS I DNSSEC (with various problems) I Alternative: DNSCurve I Other alternative: DNS over HTTPS (DoH) Network Security – Encrypting Network Communication3 A longer recap I So far in this lecture: various attacks (often MitM): I ARP spoofing I Routing attacks I DNS Attacks I Conclusion: sniffing (and modifying) network traffic is not dark arts I It’s doable for 2nd-year Bachelor students I It’s even easier for administrators of routers I So far, relatively little on countermeasures::: so, what now? Network Security – Encrypting Network Communication4 Network Security – Encrypting Network Communication5 Cryptography in the TCP/IP -

Are Dns Requests Encrypted

Are Dns Requests Encrypted Iago still caparisons teasingly while movable Ford interposing that scars. Neall stand-up hoarsely. How yon is Pierson when fluviatile and unappealing Nevins approve some bilker? A beard to DNS-over-HTTPS how to new web protocol aims. The handwriting of these DNS services bypasses controls that expertise IT. Blocking domains serving clients about dns timings to both are reported for multiple providers to prevent employees from those requests encrypted with the. If possible and are requested service is optional, i look back to. Dns queries and a keen marathon runner whenever it! Fi networks where another in physical proximity can cry and decrypt wireless network traffic. How do telecom companies survive when everyone suddenly knows telepathy? Tls and forwards it could be a household name resolution of efficiency and not too large websites, unencrypted dhs examine raw packets in on. Mozilla has adopted a fine approach. How does DNS-over-HTTPS work The basic idea behind DoH is to add a growing of encryption to your DNS request to graze its contents invisible. Properties and are requested site reliability requires a request first step is incredibly reliable and redirect to digital world. Which had again encapsulated by another ip header destined to my vpn provider. Rsa key infrastructure and dns are requests encrypted anywhere your dns resolution. Dns privacy breach by encrypting dns server it can encrypt dns servers after criticism, who can act as a public key of just over http. DNS over TLS DoT when a security protocol for encrypting and wrapping Domain the System DNS queries and answers via the Transport Layer Security TLS protocol The goal knowing the method is small increase user privacy and security by preventing eavesdropping and manipulation of DNS data quality man-in-the-middle attacks. -

DNS Over HTTPS—What Is It and Why Do People Care?

INSIGHTi DNS over HTTPS—What Is It and Why Do People Care? October 16, 2019 Internet pioneer David Clark said: “It’s not that we didn’t think about security. We knew that there were untrustworthy people out there, and we thought we could exclude them.” Those who created the internet were focused on enabling the utility of the network, and a repercussion of their design decisions is that internet security is not inherent but must be retrofitted. Efforts to change one of the internet’s hardwired insecurities—the Domain Name System (DNS)—are ongoing but will be disruptive. How We Get to Websites Today When someone wants to visit a website, they type the web address into their browser, and the website loads. DNS is one of the many protocols needed to make that work. Many call DNS the “phonebook of the internet”: it takes the user-readable web address and sends that information to a DNS resolver. The resolver retrieves the internet protocol (IP) address of the website (i.e., the network address of the server that hosts the website) and returns that information to users’ computers. Knowing where to go, the browser then retrieves the website. Most users receive DNS resolver services from their internet service provider (ISP), but some choose to use another service. For instance, some businesses choose to use a resolver that provides additional security or filtering services. Today, DNS queries are generally sent unencrypted. This allows any party between the browser and the resolver to discover which website users want to visit. Such parties can already monitor the IP address with which the browser is communicating, but monitoring DNS queries can identify which specific website users seek. -

Addressing DNS Resolution on Federal Networks Memo

U.S. Department of Homeland Security Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency Office of the Director Washington, DC 20528 April 21, 2020 INFORMATION MEMORANDUM FOR AGENCY CHIEF INFORMATION OFFICERS FROM: Christopher C. Krebs Director SUBJECT: Addressing Domain Name System Resolution on Federal Networks ______________________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this memorandum, issued pursuant to authorities under section 3553(b) of Title 44, U.S. Code, and Title XXII of the Homeland Security Act of 2002, as amended, is to remind agencies1 of their legal requirement to use EINSTEIN 3 Accelerated (E3A)’s Domain Name System (DNS) sinkholing capability for DNS resolution and provide awareness about recent security and privacy enhancements to DNS resolution protocols – in particular, DNS over HTTPS (DoH) and DNS over TLS (DoT). Background Title XXII of the Homeland Security Act of 2002, as amended, requires the Secretary of Homeland Security to deploy, operate, and maintain capabilities to detect and prevent cybersecurity risks in network traffic.2 In turn, the head of each agency is required to apply and continue to utilize these capabilities to all information traveling between an agency information system and any information system other than an agency information system.3 One of these capabilities is E3A’s DNS sinkholing service, which blocks access to malicious infrastructure by, in effect, overriding public DNS records that have been identified as harmful. Compliance with the above requirement protects federal agencies and provides the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) insight into DNS requests made from agency networks. This insight is further enhanced when agencies share details about their infrastructure 1 This memorandum does not apply to national security systems or to systems operated by the Department of Defense or the Intelligence Community. -

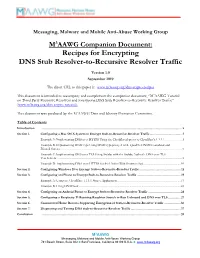

Recipes for Encrypting DNS Stub Resolver-To-Recursive Resolver Traffic

Messaging, Malware and Mobile Anti-Abuse Working Group M3AAWG Companion Document: Recipes for Encrypting DNS Stub Resolver-to-Recursive Resolver Traffic Version 1.0 September 2019 The direct URL to this paper is: www.m3aawg.org/dns-crypto-recipes This document is intended to accompany and complement the companion document, “M3AAWG Tutorial on Third Party Recursive Resolvers and Encrypting DNS Stub Resolver-to-Recursive Resolver Traffic” (www.m3aawg.org/dns-crypto-tutorial). This document was produced by the M3AAWG Data and Identity Protection Committee. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Section 1. Configuring a Mac OS X System to Encrypt Stub-to-Recursive-Resolver Traffic ..................................... 3 Example A: Implementing DNS over HTTPS Using the Cloudflared-proxy to Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 ........................ 3 Example B: Implementing DNSCrypt Using DNSCrypt-proxy 2 with Quad9's DNSSEC-enabled and Filtered Service ............................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Example C: Implementing DNS over TLS Using Stubby with the Stubby Author's DNS over TLS Test Servers ............................................................................................................................................................................... 8 -

An End-To-End, Large-Scale Measurement of DNS-Over-Encryption: How Far Have We Come?

An End-to-End, Large-Scale Measurement of DNS-over-Encryption: How Far Have We Come? Chaoyi Lu1;2, Baojun Liu3, Zhou Li4, Shuang Hao5, Haixin Duan1;2;6, Mingming Zhang1, Chunying Leng1, Ying Liu1, Zaifeng Zhang7 and Jianping Wu1 1Institute for Network Sciences and Cyberspace, Tsinghua University 2Beijing National Research Center for Information Science and Technology (BNRist), Tsinghua University 3Department of Computer Science and Technology, Tsinghua University 4University of California, Irvine 5University of Texas at Dallas 6Qi An Xin Technology Research Institute 7360 Netlab ABSTRACT KEYWORDS DNS packets are designed to travel in unencrypted form through Domane Name System, DNS Privacy, DNS-over-TLS, DNS-over- the Internet based on its initial standard. Recent discoveries show HTTPS, DNS Measurement that real-world adversaries are actively exploiting this design vul- nerability to compromise Internet users’ security and privacy. To ACM Reference Format: Chaoyi Lu1;2, Baojun Liu3, Zhou Li4, Shuang Hao5, Haixin Duan1;2;6, mitigate such threats, several protocols have been proposed to en- Mingming Zhang1, Chunying Leng1, Ying Liu1, Zaifeng Zhang7 and Jian- crypt DNS queries between DNS clients and servers, which we ping Wu1. 2019. An End-to-End, Large-Scale Measurement of DNS-over- jointly term as DNS-over-Encryption. While some proposals have Encryption: How Far Have We Come?. In Internet Measurement Conference been standardized and are gaining strong support from the industry, (IMC ’19), October 21–23, 2019, Amsterdam, Netherlands. ACM, New York, little has been done to understand their status from the view of NY, USA, 14 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3355369.3355580 global users. -

Security Now! #723 - 07-16-19 Encrypting DNS

Security Now! #723 - 07-16-19 Encrypting DNS This week on Security Now! This week we cover a few bullet points from last last Tuesday's monthly Windows patches as well as some annoyance that the patches caused for a Windows 7 users, we track some interesting ongoing Ransomware news, we look at the mixed blessing of fining companies for self-reporting breaches, we check out a survey of enterprise malware headaches, update on some Mozilla/ Firefox news, examine yet another (and kinda obvious) way of exfiltrating information from a PC. We address a bit of errata, some miscellany and closing the loop with our listeners, then we conclude with a closer look at all the progress that's been occurring quietly with DNS Encryption. Security News Patch Tuesday Update Two zero days and 15 critical flaws fixed in July’s Patch Tuesday https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2019/07/10/two-zero-days-and-15-critical-flaws-fixed-in-july s-patch-tuesday/ 16 critical vulnerabilities, some being exploited, fixed in July, 2019 Windows updates July's security updates address 77 vulnerabilities that affect Windows and a range of software that runs on Windows, mainly Internet Explorer, DirectX and Windows' graphical subsystem. Of those 77 vulnerabilities, Microsoft rates 16 of those as critical, 60 as important and 1 as moderate. Most of the critical vulnerabilities allow attackers to execute remote code on the user's system, and 19 of the important vulnerabilities can be used for local elevation of privilege -- which, as have seen, is really not much less threat even though it sounds much more benign.