English Studies & CL Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poverty, Inequality, and Development in the Philippines: Official Statistics and Selected Life Stories

European Journal of Sustainable Development (2019), 8, 1, 290-304 ISSN: 2239-5938 Doi: 10.14207/ejsd.2019.v8n1p290 Poverty, Inequality, and Development in the Philippines: Official Statistics and Selected Life Stories David Michael M. San Juan and Prince Jhay C. Agustin1 ABSTRACT Mainstream academia’s and neoliberal economists’ failure to exhaustively explain the roots of the 2008 crisis and point a way towards how the world can fully recover from it, made radical theories of poverty and income inequality more popular and relevant as ever. Official World Bank statistics on poverty and their traditional measurements are put into question and even an IMF-funded study admits that instead of delivering growth, neoliberalism has not succeeded in bringing economic development to the broadest number of people, as massive poverty and income inequality abound in many countries, more especially in the developing world. Drawing from theories on surplus value, labor exploitation, and economic dependency, this paper will present an updated critique of the official poverty line in the Philippines and how official statistics mask the true extent of poverty in the country, thereby figuratively many faces of poverty hidden if not obliterated; analyze the link between poverty and income inequality within the country’s neocolonial set-up; and present summarized selected life stories of ambulant vendors, mall personnel, fast food workers, cleaners, security guards and other typical faces of poverty in the Philippines’ macro-economically rich capital region – Metro Manila – which serve as fitting counterpoints to the official narrative. Such discussion will be the paper’s springboard in presenting an alternative plan towards sustainable development of the Philippines. -

Philippine NGO Network Report on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social,And Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

Philippine NGO Network Report on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social,and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) 1995 to Present Facilitated by the Philippine Human Rights Information Center (PhilRights), an institution of the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA) and the Urban Poor Associates (UPA) for the housing section in partnership with 101* non-government organizations, people’s organizations, alliances, and federations based in the Philippines in solidarity with the Center on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) and Terres des Hommes France (TDHF) (*Please see page iv to vi for the complete list of participating organizations.) ii Table of Contents List of Participating Organizations . p. iv Executive Summary . vii Right to Work . 26 Rights of Migrant Workers . 42 Right to Social Security . 56 Right to Housing . 71 Right to Food . 87 Right to Health . 94 Right to Water . 112 Right to Education . 121 Resource Allocation . 136 iii Participating Organizations Aksiyon Kababaihan ALMANA Alliance of Progressive Labor (APL) Alternate Forum for Research in Mindanao (AFRIM) Aniban ng Manggagawa sa Agrikultura (AMA) Asian South Pacific Bureau of Adult Education - ASPBAE ASSERT Bicol Urban Poor Coordinating Council (BUPCCI) Brethren Inc. Bukluran ng Manggagawang Pilipino (BMP) Center for Migrant Advocacy - Philippines (CMA) Civil Society Network for Education Reforms - E-Net Philippines CO – Multiversity (COM) Commission on Service, Diocese of Malolos Community Organizing for People’s Enterprise (COPE) DPGEA DPRDI Democratic Socialist Women of the Philippines (DSWP) Economic, Social and Cultural Rights-Asia (ESCR-Asia) Education Network – Philippines (E-Net) Families and Relatives of Involuntary Disappearance (FIND) Fellowship of Organizing Endeavors Inc.(FORGE) FIND – SCMR Foodfirst Information Action Network (FIAN-Phils) Freedom from Debt Coalition (FDC) FDC – Cebu FDC – Davao Homenet Philippines Homenet Southeast Asia John J. -

“Democratic” Philippines Luis V

ChasingtheWind: Assessing Teenee (Second Edition) I a r Felipe B. Miranda. | Temario G3Rivera- Editors si ‘na aia’aiees " [oes oat Chasing the Wind Assessing Philippine Democracy (Second Edition) Felipe B. Miranda | Temario C. Rivera Editors Published by the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines (CHRP) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Chasing the Wind Assessing Philippine Democracy (Second Edition) ISBN 978-971-93106-7-9 Printed in the Philippines PUBLISHED BY Commission on Human Rights, Philippines U.P. Complex, Commonwealth Avenue Diliman, Quezon City 1101, Philippipnes United Nations Development Programme Book layout and cover design by Fidel dela Torre Copyright©2016 by the CHRP, UNDP, and the authors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage retrieval system, without written permission from the authors and the publishers, except for brief review. Disclaimer: Any opinion(s) expressed therein do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Development Programme but remain solely those of the author(s). Table of Contents iii Table of Contents Foreword v by Jose Luis Martin C. Gascon Chairperson, Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines Foreword vii by Titon Mitra UNDP Country Director Prologue viii by Felipe B. Miranda Chapter 1 1 Conceptualizing and Measuring Modern Democracy Felipe B. Miranda Chapter 2 43 Rethinking Democratization in the Philippines: Elections, Political Families, and Parties Temario C. Rivera Chapter 3 75 The Never Ending Democratization of the Philippines Malaya C. Ronas Chapter 4 107 Local Governments, Civil Society, Democratization, and Development Ronald D. -

Alternative Report Concluding Observations

Alternative Report Executive Summary Right to Work Rights of Migrant Workers Right to Social Security and Protection Right to Adequate Housing Right to Food Right to Health Right to Water Right to Education Debt and ESC Rights Concluding Observations Executive Summary 19 Executive Summary 20 Philippine NGO Network Report on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), 1995 – 2008 Executive Summary IN DECEMBER 2006, the Philippine Government submitted a consolidated document of its second, third, and fourth 1. periodic reports on the implementation of the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. This report, on the other hand, is a product of a Philippine NGO initiative that started in October 2007, facilitated by the Philippine Human Rights Information Center (PhilRights) and the Urban Poor Associates (UPA) for the housing section, that reflects civil society Executive perspective on the situation of these rights and how they could be Summary further respected, protected, and fulfilled by the State. 2. Crucial to this NGO process were the three inter-island consultations conducted from August 26 to September 10, 2008 for people’s organizations (POs) and non-government organizations (NGO) based in the National Capital Region/Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. 101 individuals and 72 groups and institutions validated and improved the observations, analyses, and recommendations included in the draft reports. 3. This report was also completed in solidarity and coordination with the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) and Terre des Hommes-France (TdHF). COHRE also provided comments on the draft text during the writing of this information to the Committee. -

A Child-Centered Ethnographic Study on the Street Careers of Children in Tondo, Manila

i Graduate School of Social Sciences Research Master International Development Studies Cover Pictures: Children playing and working in Tondo, Manila. (Source: Author) ii MSc (Res) Thesis A Child-Centered Ethnographic Study on the Street Careers of Children in Tondo, Manila Charlotte Prenen Msc (Res) International Development Studies June 30th, 2017 Contact: [email protected] iii Thesis Supervision and Evaluation Supervisor: Dr. Jacobijn Olthoff Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences University of Amsterdam Nieuwe Achtergracht 166, Amsterdam [email protected] Second Reader: Dr. Yatun Sastramidjaja Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences University of Amsterdam Nieuwe Achtergracht 166, Amsterdam [email protected] iv Abstract Starting from a ‘street careers’ framework, this thesis studies the lives of children in street situations in Tondo, the Philippines. Although academic research on the lives of children in street situations is increasing, a gap persists between researcher’s interpretations and representations of children’s realities, and the heterogeneous ways that children understand their realities. Representations based on researchers’ interpretations often result in portraying children in street situations as one homogeneous group of children, posing the risk of the stigmatization and marginalization of all poor children on the street. To do justice to the heterogeneities in children’s lives, this thesis presents a ‘street careers’ framework with three pillars as building blocks: livelihoods, social identity, and life trajectories. Building on the three pillars, the empirical findings from the child-centered ethnographic research conducted in Tondo reveal substantial differences in how children experience livelihood activities and opportunities, and demonstrates how public opinion influences children’s social identity constructions differently. -

Isang Kritikal Na Pagsusuri Sa Pagpa-Pagpag Ng Mga Maralitang

Unibersidad ng Pilipinas Maynila Kolehiyo ng Agham at Sining Departamento ng Agham Panlipunan LIPUNAN, BITUKA AT ALIKABOK: Isang Kritikal na Pagsusuri sa Pagpa-Pagpag ng mga Maralitang Naninirahan sa Barangay Payatas sa Lungsod ng Quezon at Tatlong Barangay sa Tondo Slum Areas at ang Implikasyon nito sa Kanilang Panlipunang Pamumuhay Isang undergradweyt tesis bilang parsyal na katuparan sa mga rekisito sa kursong BA Araling Pangkaunlaran Ipinasa ni Cesar A. Mansal 2011-85004 BA Araling Pangkaunlaran Ipinasa kay Propesor Ida Marie Pantig Tagapayo Mayo 2016 PAGKILALA AT PASASALAMAT Naging madugo at mapanghamon ang pagsusulat ko ng tesis sa aking huling taon sa pamantasan. Kalakip ng bawat titik na inilalagak ko sa manyuskriptong ito ay ang pagtambad sa aking mga mata ng masasakit na reyalidad na hindi ko kahit kailanman inakalang masasaksihan ng aking mga mata. Naging mahapdi para sa aking damdamin ang makita ang totoong kalagayan ng mga abang maralita sa Kamaynilaan habang masayang namumuhay sa karangyaan ang marami. Ang kanilang kasadlakan sa hirap na nakikita ko araw-araw sa Tondo ang siyang nagtulak sa akin upang isulat ng pananaliksik na ito. Wala man akong kakayahan sa kasalukuyan na makatulong sa pagpapataas sa antas ng pamumuhay ng mga maralitang Pilipino, nawa’y sa pamamagitan ng panananaliksik na ito ay makapag-ambag ako ng kaalaman patungkol sa pamamagpag ng mga maralita at makapagmulat ako ng isip ng maraming Pilipinong hindi batid ang pag-iral nito. At dahil naging matagumpay ang pagsulat ko sa tesis na ito, nais kong magpasalamat at ialay ang pananaliksik na ito sa lahat ng umagapay sa akin sa araw-araw na paglubog at pag-inog sa mga pook maralita. -

27-167 Import.Pdf

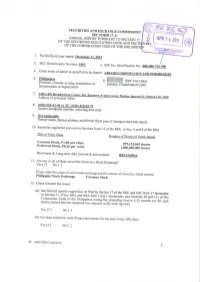

COVER SHEET FOR AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A B S - C B N C O R P O R A T I O N A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S Principal Office (No./Street/Barangay/City/Town/Province) A B S - C B N B r o a d c a s t i n g C e n t e r , S g t . E s g u e r r a A v e n u e c o r n e r M o t h e r I g n a c i a S t . Q u e z o n C i t y Form Type Department requiring the report Secondary License Type, If Applicable A A F S COMPANY INFORMATION Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Number/s Mobile Number [email protected] (632) 415-2272 ─ Annual Meeting Fiscal Year No. of Stockholders Month/Day Month/Day 5,478 May 5 December 31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Number/s Mobile Number Rolando P. Valdueza [email protected] (632) 415-2272 ─ Contact Person’s Address ABS-CBN Broadcast Center, Sgt. Esguerra Avenue corner Mother Ignacia St. Quezon City Note : In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated.