Azerbaijan by H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Care Systems in Transition

Health Care Systems in Transition Written by John Holley Oktay Akhundov Ellen Nolte Edited by Ellen Nolte Laura MacLehose Martin McKee Azerbaijan 2004 The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies is a partnership between the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, the governments of Belgium, Finland, Greece, Norway, Spain and Sweden, the European Investment Bank, the Open Society Institute, the World Bank, the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Keywords: DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE EVALUATION STUDIES FINANCING, HEALTH HEALTH CARE REFORM HEALTH SYSTEM PLANS – organization and administration AZERBAIJAN © WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2004 This document may be freely reviewed or abstracted, but not for commercial purposes. For rights of reproduction, in part or in whole, application should b e made to the Secretariat of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Scherfigsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies welcomes such applications. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies or its participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The names of countries or areas used in this document are those which were obtained at the time the original language edition of the document was prepared. -

TIGHTENING the SCREWS Azerbaijan’S Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 39176 January 2007 Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement Prepared by the Road Transport Service Department for the Asian Development Bank. The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. 2 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 2 January 2007) Currency Unit – Azerbaijan New Manat/s (AZM) AZM1.00 = $1.14 $1.00 = AZM0.87 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank DRMU – District Road Maintenance Unit EA – executing agency EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan ESS – Ecology and Safety Sector IEE – initial environmental examination MENR – Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources MFF – multitranche financing facility NOx – nitrogen oxides PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance ROW – right-of-way RRI – Rhein Ruhr International RTSD – Road Transport Service Department SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SOx – sulphur oxides TERA – TERA International Group, Inc. UNESCO – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization WHO – World Health Organization WEIGHTS AND MEASURES C – centigrade m2 – square meter mm – millimeter vpd – vehicles per day CONTENTS MAP I. Introduction 1 II. Description of the Project 3 IIII. Description of the Environment 11 A. Physical Resources 11 B. Ecological and Biological Environment 13 C. -

Global Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition

Global Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition doi: 10.39127/GJFSN:1000104 Research Article Aliev Z.H. Gl J Food Sci Nutri: GJFSN-104. The Research of The Radial Growth of The Flora Species Which Do Not Have Special Protection on The South Hillsides of Greater Caucasus Prof. Dr. Aliyev Zakir Huseyn Oglu Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan *Corresponding author: Prof. Dr. Aliyev Zakir Huseyn Oglu, Senior Scientific Officer, Erosion and Irrigation Institute of the National Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijan Republic 1007AZ. Baku city, M. Kashgay house 36, Russia. Tel: +7994 (012) 440-42-67; Email: [email protected] Citation: Aliev Z.H (2020) The Research of The Radial Growth of The Flora Species Which Do Not Have Special Protection on The South Hillsides of Greater Caucasus. Gl J Foo Sci Nutri: GJFSN:104. Received Date: 24 January, 2020; Accepted Date: 30 January, 2020; Published Date: 05 February, 2020. Abstract The radial growth of the trunks of the following flora species which do not have special protection on the south hillsides of Greater Caucasus were studied in the article: Georgioan oak- Quercus iberica M. Bieb Common hornbeam - Caprinus betulus L. Common chestnut - Castanea sativa Mill. Black walnut - Juglans nigra L., Heart leaved alder - Alnus subcordata C.A. Mey. During the dendrochronological analyses, the dynamics of growth over the years were analysed based on the distances between the tree rings. The impact of the climatic factors to the growth of the trees was analysed and the ages of tree species were investigated. -

Təbiəti Qoruyaq! Let’S Protect the Nature!

Hesabat / Report 2013 1 Təbiəti qoruyaq! Let’s protect the nature! Hesabat / Report 2013 Hesabat Report Mündəricat Content Müşahidə Şurası Sədrinin müraciəti / Statement of Supervisory Board Chairman 05 Təməl informasiya / Key information 10 Strategiya və brend quruculuğu / Principles of Corporate Strategy 13 Təşkilatlarda üzvlük / Membership in organizations 16 İdarəetmə sistemi / Management system 20 Korporativ sistem/ Corporate system 21 Təşkilati struktur / Organizational structure 24 Strateji və operativ menecment / Team: strategic and operational management 28 Xarici mühit / Environment 34 Makroiqtisadi vəziyyət / Macroeconomics 35 Bank sistemi / Banking sistem 38 Maliyyə göstəriciləri / Financial Indexes 51 Aktivlər / Assets 52 Aktivlərin dinamikası / Assets breakdown 53 Öhdəliklər / Liabilities 55 Öhdəliklərin strukturu / Liability structure 56 Kapital / Capital 57 Kredit portfeli / Loan portfolio 59 Sektorlar üzrə təhlil / Breakdown by sectors 60 Fiziki şəxslərə verilmiş kreditlər / Loans to individuals 61 Fiziki şəxslərə verilmiş kreditlərin strukturu / Structure of loans to individuals 62 Müştəri hesabları / Customer accounts 63 Gəlirlər / Income 65 Xərclər / Expenses 69 Məhsul və xidmətlər / Products and services 73 Biznes kreditləri / Loans 74 Fiziki şəxslərin kreditləşməsi / Loans to individuals 75 Vəsaitlərin cəlb olunması / Funds Raising 77 Plastik kartlar və pul köçürmə sistemləri / Plastic Cards and Money Transfer 79 FOREX 82 Filiallar / Branches 87 Fəaliyyət şəbəkəsi / Branch network 88 Filialların və şöbələrin siyahısı -

1 to the PRESIDENT of the AZERBAIJAN REPUBLIC Mr

TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE AZERBAIJAN REPUBLIC Mr. HEYDAR ALIYEV* Dear Heydar Aliyevich, According to the exchange of views on the issues of strengthening the ceasefire regime, which took place in Baku, I am sending to you, as it was agreed, the proposals of the Minsk Conference co- chairmen. The proposals of the mediator on strengthening the ceasefire in the Nagorno Karabakh conflict On behalf of the Co-chairmanship of the OSCE Minsk Conference (hereinafter – the Mediator), with the purpose of strengthening the ceasefire regime established in the conflict region since May 12, 1994 and creating more favourable conditions for the progress of the peace process, we jointly suggest that the conflicting sides (hereinafter – the Sides) should assume the following obligations: 1. In the event of incidents threatening the ceasefire, to immediately inform the other Side (and in a copy – the Mediator) in written form by facsimile or by the PM line with an exact specification of the place, time and character of the incident and its consequences. The other Side is informed that measures are being taken for non-admission of reciprocal actions which could lead to the aggravation of the incident. Accordingly, the other Side is expected to take appropriate measures immediately. If possible, proposals about taking urgent measures to overcome this incident as quickly as possible and restore the status quo ante are also reported. 2. Upon receiving such a notification from the other Side, to immediately check the facts and give a written response not later than within 6 hours (in a copy – to the Mediator). -

Media in a Chokehold

REPORT Azerbaijan’s broadcast media assessment Media in a Chokehold Institute for Reporters' Freedom and Safety March 2013 Azerbaijan Broadcasting Media Assessment Report- March, 2013 Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety 2 Azerbaijan Broadcasting Media Assessment Report – March, 2013 Acronyms ANS TV Azerbaijan News Service TV ATV Azad Azerbaycan TV (Free Azerbaijan Television) AzTV Azerbaijani Television BBC British Broadcasting Corporation DDT Digital Terrestrial Television EBU European Broadcasting Union EPRA European Platform of Regulatory Authorities IFEX International Freedom of Expression Exchange IRFS Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety ITR Ictimai Radio (Public Radio) ITV Ictimai Television (Public Television) NGO Non-governmental organization NTRC National Television and Radio Council OSCE Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe PSB Public Service Broadcasting RFE/RL Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty RTPA Radio and Television Production Association UGC User Generated Content 3 Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety Azerbaijan Broadcasting Media Assessment Report- March, 2013 Contents 1 Acknowledgments.................................. 5 2 Recommendations.................................. 7 Executive Summary . .............................. 17 Introduction . ............................ 20 Chapter One: Broadcasting and Media Policy . 23 Chapter Two: The National TV and Radio Council . 28 Chapter Three: Public Service Broadcasting . ....... 32 Conclusion. ............................. 37 Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety 4 Azerbaijan Broadcasting Media Assessment Report – March, 2013 Acknowledgments This report is a publication of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), an independent, non-profit organization dedicated to promoting freedom of expression in Azerbaijan. The report is part of a larger initiative, implemented by IRFS and supported by the OSCE Office in Baku--Change in the air: Advancing the debate on broadcast pluralism and diversity in Azerbaijan. -

Nationalist Rhetoric and Public Legitimacy in Ilham Aliyev’S Azerbaijan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository NATIONALIST RHETORIC AND PUBLIC LEGITIMACY IN ILHAM ALIYEV’S AZERBAIJAN Benjamin Midas A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts in the Global Studies department in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Erica Johnson Michael Morgan Chad Bryant © 2016 Benjamin Midas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Benjamin Midas: Nationalist Rhetoric and Public Legitimacy in Ilham Aliyev’s Azerbaijan (Under the Direction of Erica Johnson) This thesis explores the question of why nondemocratic leaders use nationalist rhetoric in ways very similar to democratic leaders through a case study of Azerbaijan. I argue that Azerbaijan’s president Ilham Aliyev uses nationalist rhetoric in order to build public legitimacy for his regime. Despite not needing to build a base of support for legitimate elections, Aliyev needs to legitimate his regime in the eyes of his citizens. To do so he uses nationalist themes in his speeches that resonate with Azerbaijani population to develop popular support. These themes come from applying theories of nationalism to the context of Azerbaijan. I will show the nationalist themes Aliyev utilizes in his speeches and how the use of those themes changes in response to events in Azerbaijan. Aliyev modulates his nationalist rhetoric in response to events in predictable ways, which shows how he manipulates nationalist themes to generate support. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………1 CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW………………………………………………………...11 CHAPTER 3: CASE STUDY……………………………………………………………………28 CHAPTER 4: CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..47 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………......................50 iv INTRODUCTION Azerbaijan is a small country in the southern Caucasus ruled by President Ilham Aliyev. -

Azerbaijan's Deteriorating Media Environment

Free Expression Under Attack: Azerbaijan’s Deteriorating Media Environment Report of the International Freedom of Expression Mission to Azerbaijan 7-9 September 2010 October 2010 ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7324 2500 Fax: +44 20 7490 0566 E-mail: [email protected] © ARTICLE 19, London, 2010 ISBN 978-1-906586-21-8 This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial- ShareAlike 2.5 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, provided you: 1) give credit to ARTICLE 19; 2) do not use this work for commercial purposes; 3) distribute any works derived from this publication under a licence identical to this one. To access the full legal text of this licence, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/legalcode This report is published thanks to generous support from Open Society Institute - Assistance Foundation/Azerbaijan, which also provided support for the coordination of the mission. List of endorsing organizations This report was written and endorsed by (in alphabetical order): ARTICLE 19: Global Campaign for Free Expression Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R United Kingdom Contact: Rebecca Vincent Azerbaijan Advocacy Assistant E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 207324 2500 www.article19.org Freedom House 1301 Connecticut Avenue NW Floor 6 Washington D.C. 20036 USA Contact: Courtney C. Radsch Senior Program Officer E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +1 202 296 -

Azerbaijan | Freedom House

Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan About Us DONATE Blog Mobile App Contact Us Mexico Website (in Spanish) REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Subscribe Donate NATIONS IN TRANSIT - View another year - ShareShareShareShareShareMore 7 Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Nations in Transit 2014 DRAFT REPORT 2014 SCORES PDF version Capital: Baku 6.68 Population: 9.3 million REGIME CLASSIFICATION GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,410 Consolidated Source: The data above are drawn from The World Bank, Authoritarian World Development Indicators 2014. Regime 6.75 7.00 6.50 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 1 of 23 6/25/2014 11:26 AM Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan Azerbaijan is ruled by an authoritarian regime characterized by intolerance for dissent and disregard for civil liberties and political rights. When President Heydar Aliyev came to power in 1993, he secured a ceasefire in Azerbaijan’s war with Armenia and established relative domestic stability, but he also instituted a Soviet-style, vertical power system, based on patronage and the suppression of political dissent. Ilham Aliyev succeeded his father in 2003, continuing and intensifying the most repressive aspects of his father’s rule. -

SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR

SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR Aslan Ismayilov SUMGAYIT - BEGINNING OF THE COLLAPSE OF THE USSR 1 Aslan Ismayilov ЧАШЫОЬЛУ 2011 Aslan Ismayilov Sumgayit – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR Baku Aslan Ismayilov Sumgayit – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR Baku Translated by Vagif Ismayil and Vusal Kazimli 2 SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR SUMGAYIT PROCEEDINGS 3 Aslan Ismayilov 4 SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR HOW I WAS APPOINTED AS THE PUBLIC PROSECUTOR IN THE CASE AND OBTAINED INSIGHT OF IT Dear readers! Before I start telling you about Sumgayit events, which I firmly believe are of vital importance for Azerbaijan, and in the trial of which I represented the government, about peripeteia of this trial and other happenings which became echoes and continuation of the tragedy in Sumgayit, and finally about inferences I made about all the abovementioned as early as in 1989, I would like to give you some brief background about myself, in order to demonstrate you that I was not involved in the process occasionally and that my conclusions and position regarding the case are well grounded. Thus, after graduating from the Law Faculty of of the Kuban State University of Russia with honours, I was appointed to the Neftekumsk district court of the Stavropol region as an interne. After the lapse of some time I became the assistant for Mr Krasnoperov, the chairman of the court, who used to be the chairman of the Altay region court and was known as a good professional. The existing legislation at that time allowed two people’s assessors to participate in the court trials in the capacity of judges alongside with the actual judge. -

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

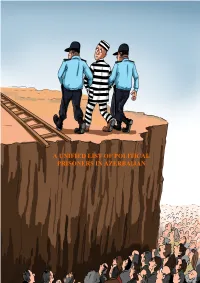

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested