Mining Camps: Myth Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Governor Ralph Carr an Archival Research Handbook to a Colorado Governor's Collection

Governor Ralph Carr An Archival Research Handbook to a Colorado Governor's Collection Ivona Elenton Institutionen för ABM Uppsatser inom arkivvetenskap ISSN 1651-6087 Magisterexamensarbete, 15 högskolepoäng, 2010, nr 75 Författare/Author Ivona Elenton. Svensk titel Guvernörens papper – Ralph Carr. En arkivvägledning för ett guvernörsarkiv i Colorado. English Title Governor Ralph Carr. An Archival Research Handbook to a Colorado Governor's Collection. Handledare/Supervisor Reine Rydén. Abstract The governor collections at the Colorado State Archives are a rich source for research and information about social science and the history of the state, but they are not always easy to research due to their differences in taxonomy through different eras. In my work with creating an archival research handbook for a governor collection I chose governor Ralph Carr to both illustrate the challenges as well as the thrills with historical research in a collection from the office of the governor. Ralph Carr's collection takes patience to research. Some series will have inconsistent taxonomy and other series lack sub-series, and if a researcher is not familiar with the terminology of state affairs, many documents can pose a challenge. It is my hope that this handbook will be of use for both amateur researchers as well as provide a few short-cuts for more seasoned scholars. Governor Carr's collection covers some of the most dramatic years in Colorado history, the first part of WWII, and it is frequently requested for research, but many researchers get stuck between the vast amount of documents only sorted by dates, for instance in the series marked "Council of Defense", which contains many interesting documents about the Japanese-Americans who were to be deported to the Granada Relocation camp, or Camp Amache, as it was popularly called. -

“John Long Routt” by Mary Peterson, Forest Supervisor

100 YEARS OF CONSERVATION AND PUBLIC SERVICE ON THE ROUTT NATIONAL FOREST “John Long Routt” by Mary Peterson, Forest Supervisor Celebrating the Routt National Forest’s centennial wouldn’t be right without some recognition of the man for whom the Forest was named, John Long Routt. John Long Routt was the last territorial and first state governor of Colorado. He was born in Eddyville, Kentucky on April 25, 1826. Soon after his birth, his family moved to Bloomington, Illinois, where Routt obtained a public school education. Later he became a carpenter and was especially interested in architecture. While living in Illinois, Routt became a town alderman and was elected Sheriff of McLean County. Routt's civil career, however, was interrupted by the Civil War, during which time he began to display some of his remarkable talents for organization and leadership. Routt organized the 94th Illinois Volunteer Regiment, was elected Captain, and served heroically at the battle of Vicksburg and Prairie Grove. Attaining a reputation as a resourceful and valorous individual, Routt was promoted to Colonel by General Ulysses S. Grant. Routt returned to Illinois in 1865 to find himself on the Republican ticket for county treasurer, a post he held successfully for two terms. In 1869 Routt was appointed chief clerk to the second assistant postmaster general, a post he relinquished due to his appointment as a United States Marshal in Illinois. Routt held this office until 1871 when he became the Second Assistant Postmaster General. After ten years and four government positions, President Grant rewarded Routt with the Territorial Governorship of Colorado on March 29, 1875. -

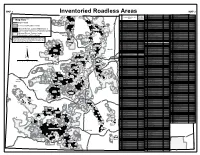

Rulemaking for Colorado Roadless Areas Map 2

MAP 2 Inventoried Roadless Areas MAP 2 IRA acres 114 Porphyry Peak 3,400 233 Treasure Mountain 20,900 194 115 Puma 8,500 234 Turkey Creek 22,300 193 Platte River Inventoried Roadless Area rounded 116 Purgatoire 13,200 235 West Needle 2,500 Wilderness Names to nearest 207 117 Rampart West 23,700 236 West Needle Wilderness 5,900 4 100 acres ** Map Key ** 24 118 Romley 6,900 237 Williams Creek White Fir Natural Area 500 209 Arapaho-Roosevelt National Forest 119 Sangre de Cristo 32,600 White River National Forest 187 204 193 Mount 1 Bard Creek 25,400 120 Scraggy Peaks 8,200 238 Adam Mountain 8,200 195 197 21 Major Roads Zirkel 2 Byers Peak 10,100 121 Sheep Rock 2,200 239 Ashcroft 900 Wilderness 210 205 24 76 208 Rawah 10 25 3 Cache La Poudre Adjacent Areas 3,200 122 Silverheels 6,600 240 Assignation Ridge 13,300 Wilderness 9 11 4 Cherokee Park 7,800 123 Spanish Peaks 5,700 241 Baldy Mountain 6,000 Inventoried Roadless Areas 5 3 5 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas 46,000 124 Spanish Peaks- proposed 1,300 242 Basalt Mountain A 14,000 196 5 3 3 5 5 Cache La Poudre 6 Copper Mountain 13,500 125 Square Top Mountain 5,900 243 Basalt Mountain B 7,400 5 3 3 3 214 Wilderness 7 Crosier Mountain 7,200 126 St. Charles Peak 11,600 244 Berry Creek 8,600 National Forest System Wilderness & Comanche Peak 28 200 24 8 Gold Run 6,500 245 Big Ridge To South Fork A 35,300 191 Wilderness 127 Starvation Creek 8,200 19 5 9 Green Ridge - East 26,700 128 Tanner Peak 17,800 246 Big Ridge To South Fork B 6,000 Other Congressionally Designated Lands 24 Fort 19 5 10 Green Ridge -

Spanish Peaks Wilderness

Mt. Bierstadt Field Trip Trip date: 6/17/2006 Ralph Swain, USFS R2 Wilderness Program Manager Observations: 1). The parking lot was nearly full (approximately 35 + vehicles) at 8:00 am on a Saturday morning. I observed better-than-average compliance with the dog on leash regulation. Perhaps this was due to my Forest Service truck being at the entrance to the parking lot and the two green Forest Service trucks (Dan and Tom) in the lot! 2). District Ranger Dan Lovato informed us of the District’s intent to only allow 40 vehicles in the lower parking lot. Additional vehicles will have to drive to the upper parking lot. This was new information for me and I’m currently checking in with Steve Priest of the South Platte Ranger District to learn more about the parking situation at Mt. Bierstadt. 3). I observed users of all types and abilities hiking the 14er. Some runners, 14 parties with dogs (of which 10 were in compliance with the dog-leash regulation), and a new- born baby being carried to the top by mom and dad (that’s a first for me)! Management Issues: 1). Capacity issue: I counted 107 people on the hike, including our group of 14 people. The main issue for Mt. Bierstadt, being a 14er hike in a congressionally designated wilderness, is a social issue of how many people are appropriate? Thinking back to Dr. Cordell’s opening Forum discuss on demographic trends and the growth coming to the west, including front-range Denver, the use on Mt. -

Directory of Government Officials 2019

The LEAGUE of WOMEN VOTERS of Pueblo Directory of Governmental Officials for Pueblo County 2019 Online at www.lwvpueblo.org 719-470-0723 www.lwvpueblo.org PREFACE This booklet is prepared by the League of Women Voters of Pueblo, Inc. to promote political responsibility through informed and active participation of citizens in government. Through its Voter Services/Citizen Information activities, the League provides nonpartisan information on candidates and issues. Further information about the League of Women Voters may be obtained by calling 470-0723, by writing: LWV Pueblo • P.O. Box 521 • Pueblo, CO 81002 or online at www.lwvpueblo.org and on Facebook TABLE OF CONTENTS Voting Qualifications ............................................................................................ 3 Registration Information ...................................................................................... 3 Election Information ............................................................................................ 4 Mail-in Ballots .................................................................................................... 5 National Officials ................................................................................................. 6 State Officials ..................................................................................................... 7 Courts .............................................................................................................. 10 County Government ......................................................................................... -

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geochronology Database for Central Colorado By T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt, 2009, Geochronology database for central Colorado: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 489, 13 p. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 -

Chapter W-9 - Wildlife Properties

07/15/2021 CHAPTER W-9 - WILDLIFE PROPERTIES Index Page ARTICLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS #900 REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL WILDLIFE 1 PROPERTIES, EXCEPT STATE TRUST LANDS ARTICLE II PROPERTY SPECIFIC PROVISIONS #901 PROPERTY SPECIFIC REGULATIONS 8 ARTICLE III STATE TRUST LANDS #902 REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL STATE TRUST LANDS 53 LEASED BY COLORADO PARKS AND WILDLIFE #903 PROPERTY SPECIFIC REGULATIONS 55 ARTICLE IV STATE FISH UNITS #904 REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL STATE FISH UNITS 71 #905 PROPERTY SPECIFIC REGULATIONS 72 ARTICLE V BOATING RESTRICTIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL DIVISION CONTROLLED PROPERTIES, INCLUDING STATE TRUST LANDS LEASED BY COLORADO PARKS AND WILDLIFE #906 AQUATIC NUISANCE SPECIES (ANS) 72 APPENDIX A 74 APPENDIX B 75 Basis and Purpose 81 Statement CHAPTER W-9 - WILDLIFE PROPERTIES ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS #900 - REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL WILDLIFE PROPERTIES, EXCEPT STATE TRUST LANDS A. DEFINITIONS 1. “Aircraft” means any machine or device capable of atmospheric flight, including, but not limited to, airplanes, helicopters, gliders, dirigibles, balloons, rockets, hang gliders and parachutes, and any models thereof. 2. "Water contact activities" means swimming, wading (except for the purpose of fishing), waterskiing, sail surfboarding, scuba diving, and other water-related activities which put a person in contact with the water (without regard to the clothing or equipment worn). 3. “Youth mentor hunting” means hunting by youths under 18 years of age. Youth hunters under 16 years of age shall at all times be accompanied by a mentor when hunting on youth mentor properties. A mentor must be 18 years of age or older and hold a valid hunter education certificate or be born before January 1, 1949. -

A Compendium of Niosh Mining Research 2002

A COMPENDIUM OF NIOSH MINING RESEARCH 2002 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Washington, DC December 2001 ORDERING INFORMATION Copies of National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) documents and information about occupational safety and health are available from NIOSH–Publications Dissemination 4676 Columbia Parkway Cincinnati, OH 45226-1998 FAX: 513-533-8573 Telephone: 1-800-35-NIOSH (1-800-356-4674) E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.cdc.gov/niosh This document is the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. Disclaimer: Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by NIOSH. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2002-110 FOREWORD The mining community serves the needs of our Nation in virtually every aspect of our daily lives by providing the materials we use for construction, electronics, manufacturing, energy, agriculture, medicine, and electricity. This industry has demonstrated time and time again an almost unbelievable ability to rise to any and all challenges it faces. Productivity has increased over the past 20 years to levels never before imagined, and the industry operates in one of the most difficult and challenging environments imaginable. The professionalism and pride of our mine workers are unmatched throughout the world, and our mining community is held in the highest regard around the globe. Interactions with mining professionals from other countries have always left me with a deep feeling of respect for what our mining community accomplishes. The recent tragedy we faced with the coal mine explosion in Alabama is a reminder to all of us about the dangers of rock and mineral extraction. -

UNSCEAR 2006 Report to the General Assembly with Scientific Annexes

EFFECTS OF IONIZING RADIATION United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation UNSCEAR 2006 Report to the General Assembly with Scientific Annexes VOLUME II Scientific Annexes C, D and E UNITED NATIONS New York, 2009 NOTE The report of the Committee without its annexes appears as Official Records of the General Assembly, Sixty-first Session, Supplement No. 46 and corrigendum (A/61/46 and Corr. 1). The report reproduced here includes the corrections of the corrigendum. The designation employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations con- cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The country names used in this document are, in most cases, those that were in use at the time the data were collected or the text prepared. In other cases, however, the names have been updated, where this was possible and appropriate, to reflect political changes. UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.09.IX.5 ISBN 978-92-1-142270-2 Corrigendum to Sales No. E.09.IX.5 May 2011 Effects of Ionizing Radiation: United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation 2006 Report to the General Assembly, with Scientific Annexes—Volume II Annex E (“Sources-to-effects assessment for radon in homes and workplaces”), paragraph 460 The ninth sentence should read For residential exposure to 150 Bq/m3, the authors estimated a combined OR of 1.1 (95% CI: 1.0, 1.3). -

Broadway East (Running North and South)

ROTATION OF DENVER STREETS (with Meaning) The following information was obtained and re-organized from the book; Denver Streets: Names, Numbers, Locations, Logic by Phil H. Goodstein This book includes additional information on how the grid came together. Please email [email protected] with any corrections/additions found. Copy: 12-29-2016 Running East & West from Broadway South Early businessman who homesteaded West of Broadway and South of University of Denver Institutes of Higher Learning First Avenue. 2000 ASBURY AVE. 50 ARCHER PL. 2100 EVANS AVE.` 2700 YALE AVE. 100 BAYAUD AVE. 2200 WARREN AVE. 2800 AMHERST AVE. 150 MAPLE AVE. 2300 ILIFF AVE. 2900 BATES AVE. 200 CEDAR AVE. 2400 WESLEY AVE. 3000 CORNELL AVE. 250 BYERS PL. 2500 HARVARD AVE. 3100 DARTMOUTH 300 ALAMEDA AVE. 2600 VASSAR AVE. 3200 EASTMAN AVE. 3300 FLOYD AVE. 3400 GIRARD AVE. Alameda Avenue marked the city 3500 HAMPDEN AVE. limit until the town of South 3600 JEFFERSON AVE. Denver was annexed in 3700 KENYON AVE. 1894. Many of the town’s east- 3800 LEHIGH AVE. west avenues were named after 3900 MANSFIELD AVE. American states and 4000 NASSAU AVE. territories, though without any 4100 OXFORD AVE. clear pattern. 4200 PRINCETON AVE. 350 NEVADA PL. 4300 QUINCY AVE. 400 DAKOTA AVE. 4400 RADCLIFF AVE. 450 ALASKA PL. 4500 STANFORD AVE. 500 VIRGINIA AVE. 4600 TUFTS AVE. 600 CENTER AVE. 4700 UNION AVE. 700 EXPOSITION AVE. 800 OHIO AVE. 900 KENTUCKY AVE As the city expanded southward some 1000 TENNESSEE AVE. of the alphabetical system 1100 MISSISSIPPI AVE. disappeared in favor 1200 ARIZONA AVE. -

Broad Overview Reputation of Mining and Exploration

INFACT DELIVERABLE D2.3 BROAD OVERVIEW REPUTATION OF MINING AND EXPLORATION Summary: This study analyses the reputation and attitudes towards mining and mineral exploration in the three reference countries of INFACT Project (Spain, Finland and Germany) and in leading mining countries based on literature review. The report reflects the difference in availability of literature on this matter between Finland and the other reference countries, mainly explained by differences in the evolution and development of the mining sector over the last decades. Mineral exploration is inherently perceived as a prior stage of mining production itself. The general acceptance of mining in Europe is slightly positive, being higher in traditional mining regions. The main factors laying out mining reputation or acceptance are the trust in public governance over mining companies, the potential negative environmental impacts perceived and the fairness of wealth distribution within local communities. Authors: Asistencias Técnicas University of Eastern Suomen Dialogik (DIA) Clave (ATC) Finland (UEF) Ymparistokeskus (SYKE) Virginia del Río Juha M. Kotilainen Sari Kauppi Ludger Benighaus Javier GómeZ Tuija Mononen Kari Oinonen Christina Benighaus Jari Lyytimäki Matti Kattainen Lisa Kastl Spain Finland Germany INFACT DELIVERABLE D2.3 Title: Broad overview reputation of mining and exploration Lead beneficiary: At Clave (ATC) Other beneficiaries: ITA-Suomen Yliopisto – University of Eastern Finland (UEF) Dialogik (DIA) Suomen Ymparistokeskus (SYKE) Due date: 30th April -

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published by the State Historical and Natural History Society of Colorado

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published by The State Historical and Natural History Society of Colorado VOL. Ill Denver Colorado, August, 1926 NO. 3 The Colorado Constitution By Henry J. Hersey (Formerly Judge of the District Court of Denver) Colorado's admission to the Union is not alone significant because it occurred 100 years after the Declaration of Independ ence, but also because the efforts for governmental independence were accompanied by heroic and almost revolutionary (though peaceful) acts. The early settlers and gold seekers of 1858 found themselves in a country which the various explorers had reported as a barren desert and worthless for human habitation ; though nominally a part of the Territory of Kansas, yet it was so remote, because of the slow means of transportation and communication, that it was outside the pale of governmental consideration or interest, and the pioneers were forced by existing conditions to establish some sort of a government, provide courts and make laws for themselves. So on the plains we find them quickly creating the People's Courts by the methods of pure democracies, assemblies of the peo ple hurriedly called together and accused persons brought before them and tried before a judge selected from the people, the people themselves acting as a jury ;1 in the mountains a civil, rather than a criminal, court was the need of the hour and the Miners' Court was created, having, however, both civil and criminal jurisdiction. The Miners' Court was also established by the mass meeting meth ods used in the ancient, pure democracies, for representative or republican form of government is always a matter of growth and later development.