Oh C’Mon, Those Stories Can’T Count in Continuity!’ Squirrel Girl and the Problem of Female Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Marvel Universe by Hasbro

Brian's Toys MARVEL Buy List Hasbro/ToyBiz Name Quantity Item Buy List Line Manufacturer Year Released Wave UPC you have TOTAL Notes Number Price to sell Last Updated: April 13, 2015 Questions/Concerns/Other Full Name: Address: Delivery Address: W730 State Road 35 Phone: Fountain City, WI 54629 Tel: 608.687.7572 ext: 3 E-mail: Referred By (please fill in) Fax: 608.687.7573 Email: [email protected] Guidelines for Brian’s Toys will require a list of your items if you are interested in receiving a price quote on your collection. It is very important that we Note: Buylist prices on this sheet may change after 30 days have an accurate description of your items so that we can give you an accurate price quote. By following the below format, you will help Selling Your Collection ensure an accurate quote for your collection. As an alternative to this excel form, we have a webapp available for http://buylist.brianstoys.com/lines/Marvel/toys . STEP 1 Please note: Yellow fields are user editable. You are capable of adding contact information above and quantities/notes below. Before we can confirm your quote, we will need to know what items you have to sell. The below list is by Marvel category. Search for each of your items and enter the quantity you want to sell in column I (see red arrow). (A hint for quick searching, press Ctrl + F to bring up excel's search box) The green total column will adjust the total as you enter in your quantities. -

Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 by Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane

ARCHIVE: Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 By Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane The date of the cyclone refers to the day of landfall or the day of the major impact if it is not a cyclone making landfall from the Coral Sea. The first number after the date is the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) for that month followed by the three month running mean of the SOI centred on that month. This is followed by information on the equatorial eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures where: W means a warm episode i.e. sea surface temperature (SST) was above normal; C means a cool episode and Av means average SST Date Impact January 1858 From the Sydney Morning Herald 26/2/1866: an article featuring a cruise inside the Barrier Reef describes an expedition’s stay at Green Island near Cairns. “The wind throughout our stay was principally from the south-east, but in January we had two or three hard blows from the N to NW with rain; one gale uprooted some of the trees and wrung the heads off others. The sea also rose one night very high, nearly covering the island, leaving but a small spot of about twenty feet square free of water.” Middle to late Feb A tropical cyclone (TC) brought damaging winds and seas to region between Rockhampton and 1863 Hervey Bay. Houses unroofed in several centres with many trees blown down. Ketch driven onto rocks near Rockhampton. Severe erosion along shores of Hervey Bay with 10 metres lost to sea along a 32 km stretch of the coast. -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

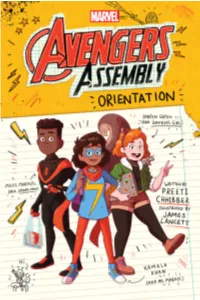

Avengersassembly Orientation

By Preeti Chhibber Illustrated by James Lancett Scholastic Inc. © 2020 MARVEL All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. scholastic and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 978-1-338-58725-8 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Printed in the U.S.A. 23 First printing 2020 Book design by Katie Fitch HERO CARD #148 powers NAME: KAMALA KHAN, AKA MS. MARVEL POWERS: Embiggening! Disembiggening! Stretching! Shape-shifting! ms. marvel HERO CARD #477 powers NAME: MILES MORALES, AKA ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN POWERS: Wall-crawling, expo- nential strength, electric shocks, being invisible, but not being creepy like a spider, that is for sure. spider-man HERO CARD #091 powers NAME: DOREEN GREEN, AKA SQUIRREL GIRL POWERS: Powers of a squirrel and (more importantly) powers of a girl. -

New Spideys Spark New Movie

December 18 , 2018 CK Reporter of the Week Katherine Gagner, Boulder New Spideys spark new movie pider Man into the Spider Verse” brings superhero movie stuff, but “Spider Man into the “Spider Man into the Spider Verse” is rated PG, and is something entirely new to the Spider Man Spider Verse” is different from other superhero movies definitely a family-friendly movie. There is no graphic “Smovie franchise. because of its focus on the characters’ relationships violence, crude humor, or cursing. In fact, it brings six entirely new things to the Spider with their families and friends. Any viewer over eight years old will enjoy this movie Man movie franchise! Like the traditional Spider Man, this movie includes and be able to follow the plot and get most of the Those six things are six unique Spider people, a difficult relationship between Miles, his father jokes. including Spiderwoman, SpiderHam (aka Peter Porker), and his uncle, but the other characters also have Viewers who are already familiar with the and SpiderNoir. interesting backstories. Spiderman story will especially enjoy this movie These additions to the Spiderman story make this These relationship stories do not slow the movie because it relies on some elements of the traditional animated movie funny, dramatic, and action-packed. down, and, in fact, the movie picks up pace and gets storyline, but someone who has not seen the movies Although it is a cartoon, “Spider Man into the Spider funnier when the other Spiderpeople enter the movie. or read the comic books will certainly be able to enjoy Verse” is not childish. -

The Empowering Squirrel Girl Jayme Horne Submitted for History of Art 390 Feminism and History of Art Professor Ellen Shortell M

The Empowering Squirrel Girl Jayme Horne Submitted for History of Art 390 Feminism and History of Art Professor Ellen Shortell Massachusetts College of Art and Design All the strength of a squirrel multiplied to the size of a girl? That must be the Unbeatable Squirrel Girl (fig. 1)! This paper will explore Marvel’s Squirrel Girl character, from her introduction as a joke character to her 2015 The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl comic series which is being harold as being extremely empowering. This paper aims to understand why a hero like Squirrel Girl would be harold and celebrated by fans, while other female heroes with feminist qualities like Captain Marvel or the New Almighty Thor might be receiving not as much praise. Squirrel Girl was created by Will Murray and artist Steve Ditko. Despite both of them having both worked for Marvel and DC, and having written stories about fan favorites like Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, Iron Man, and others, they are most known for creating Squirrel Girl, also known as Doreen Green. Her powers include superhuman strength, a furry, prehensile tail (roughly 3-4 feet long), squirrel-like buck teeth, squirrel-like retractable knuckle claws, as well as being able to communicate with squirrels and summon a squirrel army. She was first introduced in 1991, where she ambushed Iron Man in attempt to impress him and convince him to make her an Avenger. That’s when they were attacked one of Marvel’s most infamous and deadly villains, Doctor Doom. After Doctor Doom has defeated Iron Man, Squirrel Girl jumps in with her squirrel army and saves Iron Man1 (fig. -

Marvel Comics Marvel Comics

Roy Tho mas ’Marvel of a ’ $ Comics Fan zine A 1970s BULLPENNER In8 th.e9 U5SA TALKS ABOUT No.108 MARVELL CCOOMMIICCSS April & SSOOMMEE CCOOMMIICC BBOOOOKK LLEEGGEENNDDSS 2012 WARREN REECE ON CLOSE EENNCCOOUUNNTTEERRSS WWIITTHH:: BIILL EVERETT CARL BURGOS STAN LEE JOHN ROMIITA MARIIE SEVERIIN NEAL ADAMS GARY FRIIEDRIICH ALAN KUPPERBERG ROY THOMAS AND OTHERS!! PLUS:: GOLDEN AGE ARTIIST MIKE PEPPE AND MORE!! 4 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 6 2 8 1 Art ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Human Torch & Sub-Mariner logos ™ Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 108 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) AT LAST! Ronn Foss, Biljo White LL IN Mike Friedrich A Proofreader COLOR FOR Rob Smentek .95! Cover Artists $8 Carl Burgos & Bill Everett Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Writer/Editorial: Magnificent Obsession . 2 “With The Fathers Of Our Heroes” . 3 Glenn Ald Barbara Harmon Roy Ald Heritage Comics 1970s Marvel Bullpenner Warren Reece talks about legends Bill Everett & Carl Burgos— Heidi Amash Archives and how he amassed an incomparable collection of early Timelys. Michael Ambrose Roger Hill “I’m Responsible For What I’ve Done” . 35 Dave Armstrong Douglas Jones (“Gaff”) Part III of Jim Amash’s candid conversation with artist Tony Tallarico—re Charlton, this time! Richard Arndt David Karlen [blog] “Being A Cartoonist Didn’t Really Define Him” . 47 Bob Bailey David Anthony Kraft John Benson Alan Kupperberg Dewey Cassell talks with Fern Peppe about her husband, Golden/Silver Age inker Mike Peppe. -

Gerry Conway Mike Del Mundo Clayton Crain Devin Lewis

SERIAL KILLER CLETUS KASADY BONDED WITH A DERANGED ALIEN SYMBIOTE THAT GRANTED HIM POWERS SIMILAR TO THOSE OF SPIDER-MAN AND ENABLED HIM TO CRAFT BLADED WEAPONS OUT OF THE CREATURE’S ORGANIC TISSUE. WITH NEWFOUND POWER TO ACT OUT HIS DEADLIEST IMPULSES, CLETUS BECAME LED BY CLAIRE DIXON, THE F.B.I. CREATED A TASK FORCE TO CAPTURE CARNAGE. DIXON ENLISTED JOHN JAMESON, WAR HERO AND ASTRONAUT, AND EDDIE BROCK, FORMER HOST TO THE VENOM SYMBIOTE, AND DEVISED A PLAN TO CAPTURE THE RED MENACE IN AN ABANDONED MINE. THE MINE’S OWNER, BARRY GLEASON, VOLUNTEERED MANUELA CALDERONTHE MINE’S DIRECTOR OF SECURITY AND THE SOLE SURVIVOR OF CLETUS’ FIRST HOMICIDAL RAMPAGEAS BAIT TO LURE CARNAGE TO THEIR FACILITY. THE PLAN TO USE SONIC WEAPONRY TO TRAP CARNAGE WENT HORRIBLY WRONG WHEN IT COLLAPSED THE GROUND BENEATH THE KILLER, DROPPING HIM AND SEVERAL F.B.I. AGENTS INTO THE MINE BELOW. GERRY CONWAY MIKE PERKINS ANDY TROY VC’S JOE SABINO WRITER ARTIST COLOR ARTIST LETTERER MIKE DEL MUNDO CLAYTON CRAIN DEVIN LEWIS NICK LOWE COVER ARTIST VARIANT COVER ARTIST ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PUBLISHER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER CARNAGE No. 2, January 2016. Published Monthly except in November by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2015 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental.