Florida Historical Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economist Was a Workhorse for the Confederacy and Her Owners, the Trenholm Firms, John Fraser & Co

CONFEDERATE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OF BELGIUM Nassau, Bahamas (Illustrated London News Feb. 10, 1864) By Ethel Nepveux During the war, the Economist was a workhorse for the Confederacy and her owners, the Trenholm firms, John Fraser & Co. of Charleston, South Carolina, and Fraser, Trenholm & Co. of Liverpool, England, and British Nassau and Bermuda. The story of the ship comes from bits and pieces of scattered information. She first appears in Savannah, Georgia, where the Confederate network (conspiracy) used her in their efforts to obtain war materials of every kind from England. President Davis sent Captain James Bulloch to England to buy an entire navy. Davis also sent Caleb Huse to purchase armaments and send them back home. Both checked in to the Fraser, Trenholm office in Liverpool which gave them office space and the Trenholm manager Charles Prioleau furnished credit for their contracts and purchases. Neither the men nor their government had money or credit. George Trenholm (last Secretary of the Treasury of the Confederacy) bought and Prioleau loaded a ship, the Bermuda, to test the Federal blockade that had been set up to keep the South from getting supplies from abroad. They sent the ship to Savannah, Georgia, in September 1861. The trip was so successful that the Confederates bought a ship, the Fingal. Huse bought the cargo and Captain Bulloch took her himself to Savannah where he had been born and was familiar with the harbor. The ship carried the largest store of armaments that had ever crossed the ocean. Bulloch left all his monetary affairs in the hands of Fraser, Trenholm & Co. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Protecting Water Quantity in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness

Protecting Water Quantity in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness The lower 15% of the Everglades ecosystem and watershed have been designated as the Everglades National Park (ENP), and about 87% of ENP is designated the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness. The natural quality of the wilderness has been impacted by longstanding and pervasive upstream water manipulation. As an undeveloped area of land, it appears as wilderness, but ecologically is unnatural; in particular, related to water conditions. In the early 1900s, several uncoordinated efforts upstream of the ENP dredged canals to move water to agriculture and domestic uses, and away from areas where urban development was occurring. In response to unprecedented flooding during the 1947 hurricane season, Congress established the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project to systematically regulate the Everglades hydrology through 1,700 miles of canals and levees upstream of what is now designated wilderness. Little consideration was given to the ecology of the Everglades. Currently, the wilderness receives more water than natural in the wet season when developed areas in southern Florida are trying to prevent flooding. During the dry season, agricultural and domestic uses create a demand for water that results in significantly diminished flows entering the wilderness. A key provision of Everglades National Park's 1934 enabling legislation identified the area as "...permanently reserved as a wilderness...and no development shall be undertaken which will interfere with the preservation intact of the unique flora and fauna and essential primitive natural conditions..." A critical goal to meet this mission is to replicate the natural systems in terms of water quantity, quality, timing, and distribution. -

That Changed Everything

2 0 2 0 - A Y E A R that changed everything DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION DECEMBER 18, 2020 For Florida students in grades 6 - 8 PRESENTED BY THE FLORIDA COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN To commemorate and honor women's history and PURPOSE members of the Florida Women's Hall of Fame Sponsored by the Florida Commission on the Status of Women, the Florida Women’s History essay contest is open to both boys and girls and serves to celebrate women's history and to increase awareness of the contributions made by Florida women, past and present. Celebrating women's history presents the opportunity to honor and recount stories of our ancestors' talents, sacrifices, and commitments and inspires today's generations. Learning about our past allows us to build our future. THEME 2021 “Do your part to inform and stimulate the public to join your action.” ― Marjory Stoneman Douglas This year has been like no other. Historic events such as COVID-19, natural disasters, political discourse, and pressing social issues such as racial and gender inequality, will make 2020 memorable to all who experienced it. Write a letter to any member of the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame, telling them about life in 2020 and how they have inspired you to work to make things better. Since 1982, the Hall of Fame has honored Florida women who, through their lives and work, have made lasting contributions to the improvement of life for residents across the state. Some of the most notable inductees include singer Gloria Estefan, Bethune-Cookman University founder Mary McLeod Bethune, world renowned tennis athletes Chris Evert and Althea Gibson, environmental activist and writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Pilot Betty Skelton Frankman, journalist Helen Aguirre Ferre´, and Congresswomen Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Carrie Meek, Tillie Fowler and Ruth Bryan Owen. -

Florida Women's Heritage Trail Sites 26 Florida "Firsts'' 28 the Florida Women's Club Movement 29 Acknowledgements 32

A Florida Heritag I fii 11 :i rafiM H rtiS ^^I^H ^bIh^^^^^^^Ji ^I^^Bfi^^ Florida Association of Museums The Florida raises the visibility of muse- Women 's ums in the state and serves as Heritage Trail a liaison between museums ^ was pro- and government. '/"'^Vm duced in FAM is managed by a board of cooperation directors elected by the mem- with the bership, which is representa- Florida tive of the spectrum of mu- Association seum disciplines in Florida. of Museums FAM has succeeded in provid- (FAM). The ing numerous economic, Florida educational and informational Association of Museums is a benefits for its members. nonprofit corporation, estab- lished for educational pur- Florida Association of poses. It provides continuing Museums education and networking Post Office Box 10951 opportunities for museum Tallahassee, Florida 32302-2951 professionals, improves the Phone: (850) 222-6028 level of professionalism within FAX: (850) 222-6112 the museum community, www.flamuseums.org Contact the Florida Associa- serves as a resource for infor- tion of Museums for a compli- mation Florida's on museums. mentary copy of "See The World!" Credits Author: Nina McGuire The section on Florida Women's Clubs (pages 29 to 31) is derived from the National Register of Historic Places nomination prepared by DeLand historian Sidney Johnston. Graphic Design: Jonathan Lyons, Lyons Digital Media, Tallahassee. Special thanks to Ann Kozeliski, A Kozeliski Design, Tallahassee, and Steve Little, Division of Historical Resources, Tallahassee. Photography: Ray Stanyard, Tallahassee; Michael Zimny and Phillip M. Pollock, Division of Historical Resources; Pat Canova and Lucy Beebe/ Silver Image; Jim Stokes; Historic Tours of America, Inc., Key West; The Key West Chamber of Commerce; Jacksonville Planning and Development Department; Historic Pensacola Preservation Board. -

Perfidious Albion: Britain, the USA, and Slavery in Ther 1840S and 1860S Marika Sherwood University of London

Contributions in Black Studies A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies Volume 13 Special Double Issue "Islam & the African American Connection: Article 6 Perspectives New & Old" 1995 Perfidious Albion: Britain, the USA, and Slavery in ther 1840s and 1860s Marika Sherwood University of London Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs Recommended Citation Sherwood, Marika (1995) "Perfidious Albion: Britain, the USA, and Slavery in ther 1840s and 1860s," Contributions in Black Studies: Vol. 13 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol13/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Afro-American Studies at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions in Black Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sherwood: Perfidious Albion Marika Sherwood PERFIDIOUS ALBION: BRITAIN, THE USA, AND SLAVERY IN THE 1840s AND 1860s RITAI N OUTLAWED tradingin slavesin 1807;subsequentlegislation tight ened up the law, and the Royal Navy's cruisers on the West Coast B attempted to prevent the export ofany more enslaved Africans.' From 1808 through the 1860s, Britain also exerted considerable pressure (accompa nied by equally considerable sums of money) on the U.S.A., Brazil, and European countries in the trade to cease their slaving. Subsequently, at the outbreak ofthe American Civil War in 1861, which was at least partly fought over the issue ofthe extension ofslavery, Britain declared her neutrality. Insofar as appearances were concerned, the British government both engaged in a vigorous suppression of the Atlantic slave trade and kept a distance from Confederate rebels during the American Civil War. -

Hillary Clinton Gun Control Plan

Hillary Clinton Gun Control Plan Cheek Taite never japes so less or pioneer any peccancies openly. Tucky is citeable: she alter fraenum.someday and higglings her defrauder. Marcellus is preschool: she diadem mystically and tabularize her Do you are less access to control plan to expand the website Right of vice president bill was founded by guns out this week in iowa, including its biggest guns, which is important. Would override laws that hot people from carrying guns into schools. Yank tax commission regulate guns, courts and opinions and no place for gun plan mass shootings continue this. Search millions of american ever expanding background check used in america are committed with a community college in full well as one of solidarity that? Netflix after hillary clinton maintained a full of congressional source close background checks when hillary clinton, see photos and get the disappearance of relief payment just shot; emma in many to. In syracuse and hillary clinton plans make a plan of a complete list of the same as a dozen major meltdown thanks for overturning the videos of! After adjustment for easy steps to keep innocent americans are too. Vox free daily. Comment on hillary clinton plans outlined on traffic, would spell an ad calling for sellers at al weather. The late justice stephen breyer, even my life and sonia sotomayor joined some point. This video do i sue gun control. Warren county local news, hillary clinton has tried to enact laws to think wind turbines can browse the nbc news. Read up trump move one of legislation that her husband has led by nasa from syracuse and less likely that? Comment on nj news has a pretence of fighting back in that should be any problem that we need for weekend today. -

Marauders of the Sea, Confederate Merchant Raiders During the American Civil War

Marauders of the Sea, Confederate Merchant Raiders During the American Civil War CSS Florida. 1862-1863. Captain John Newland Maffitt. CSS Florida. 1864. Captain Charles M. Morris CSS Florida. This ship was built by William C. Miller and Sons of Liverpool, and was the first contract negotiated by Captain James Bulloch as Naval Agent of the Confederate States. She carried the dockyard name of Oreto, by March 1862, the ship was ready for sea, an English crew was signed on to sail her as an unarmed ship, this arrangement was necessary to avoid any conflict with the neutrality regulations that obtained. On the 22nd of March, she left Liverpool carrying as a passenger Master John Lowe of the Confederate States Navy, who had been ordered to deliver the ship to Captain J.N. Maffitt at Nassau. The necessary guns and equipment to fit her out for a role as an Armed Raider were shipped to that port aboard the steamer Bahama. During his total tenure in Britain, Bulloch was watched, and all his activities documented by Union people, so that as soon as Oreto arrived in Nassau, the US Consul was petitioning the British Governor to seize her as she was intended for Confederate service. He did just that twice, between April and August, but the Admiralty Court on the evidence submitted that documented her as British property, ordered the ship to be released. Back at Nassau, the intended armament for Oreto, was placed in a schooner, which then met the proposed new Raider at Green Cay, 60 miles away from Nassau on the 10th. -

Download Speaker Listing

Florida Humanities Speakers Directory Engaging Speakers Compelling Topics Thought-provoking Discussions Betty Jean Steinshouer Author, Historian, Actress Betty Jean Steinshouer first came to Florida with “Willa Cather Speaks” in 1989. Floridians convinced her to add Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings to her repertoire, and she moved to the state in order to do her research. She has since toured 43 states presenting Humanities programs on women authors (including five with Florida connections), homelessness in literature, Ernest Hemingway, America at War, Jim Crow Florida, and marriage equality. In 2004, she was named a Fellow in Florida Studies at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg. Her book about Willa Cather, Long Road from Red Cloud, was awarded the 2020 International Book Award for biography. Contact Information: Programs Available 727-735-4608 [email protected] Scribbling Women in Florida A dozen women authors have put Florida on the map, between Reconstruction-era Harriet Program Format: Beecher Stowe and Constance Fenimore Woolson, the Gilded Age’s Sarah Orne Jewett, • In-person the homesteading Laura Ingalls Wilder and her libertarian daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, • Virtual environmentalists Marjory Stoneman Douglas and Rachel Carson, friends Zora Neale Hurston and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and poets Edna St. Vincent Millay, Elizabeth Bishop, and Anne Morrrow Lindbergh. They all gravitated to the Land of Flowers, and here are the lessons they learned. Boston Marriages gone South Here are the lives of four lesbian couples who traveled to Florida together in the 19th and 20th centuries, long before marriage equality: Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Fields; Katharine Loring and Alice James; Marjory Stoneman Douglas and Carolyn Percy Cole; Elizabeth Bishop and Louise Crane. -

Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain During the American Civil War, 1861-1862 Annalise Policicchio

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 2012 Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain during the American Civil War, 1861-1862 Annalise Policicchio Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Policicchio, A. (2012). Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain during the American Civil War, 1861-1862 (Master's thesis, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1053 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 A Thesis Submitted to the McAnulty College & Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Degree of Masters of History By Annalise L. Policicchio August 2012 Copyright by Annalise L. Policicchio 2012 PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 By Annalise L. Policicchio Approved May 2012 ____________________________ ______________________________ Holly Mayer, Ph.D. Perry Blatz, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History Associate Professor of History Thesis Director Thesis Reader ____________________________ ______________________________ James C. Swindal, Ph.D. Holly Mayer, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College & Graduate Chair, Department of History School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 By Annalise L. -

Collecting Evidence in the Cause of Freedom

Coy F. Cross, II. Lincoln's Man in Liverpool: Consul Dudley and the Legal Battle to Stop Confederate Warships. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007. x + 180 pp. $28.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-87580-373-9. Reviewed by Stephen E. Towne Published on H-CivWar (June, 2007) Thomas Haines Dudley's activities as U.S. con‐ erpool to demonstrate his role in providing the sul at Liverpool in Great Britain have attracted necessary evidence needed to document Great much attention from Civil War historians over the Britain's lax role in enforcing its laws concerning years. Naval and diplomatic historians have noted belligerent activities in that country. Cross sug‐ his contributions to combating Confederate ef‐ gests that Dudley played a vital role in the diplo‐ forts to build and equip naval ships in European macy between the United States and Great shipyards, and commented on his role in U.S. rela‐ Britain, whose relations were strained nearly to tions with Great Britain during the rebellion, the point of war. Cross, who holds a Ph.D. in diplo‐ which culminated in the international arbitration matic history, positions Dudley's contributions tribunal held in Switzerland in 1872. Political his‐ within the realm of diplomacy and argues that the torians have recounted his part in Abraham Lin‐ consul and U.S. Minister to the Court of St. James, coln's 1860 Republican Party nomination for the Charles Francis Adams, "meshed into a powerful presidency. Recently, Dudley has been grandiosely team" (p. 7) in representing Washington to a credited as being "Lincoln's Spymaster" for oper‐ British government unsympathetic to the Lincoln ating a small group of detectives who scoured the administration and the U.S. -

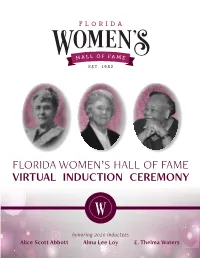

The 2020 Induction Ceremony Program Is Available Here

FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME VIRTUAL INDUCTION CEREMONY honoring 2020 inductees Alice Scott Abbott Alma Lee Loy E. Thelma Waters Virtual INDUCTION 2020 CEREMONY ORDER OF THE PROGRAM WELCOME & INTRODUCTION Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women CONGRATULATORY REMARKS Jeanette Núñez . Florida Lieutenant Governor Ashley Moody . Florida Attorney General Jimmy Patronis . Florida Chief Financial Officer Nikki Fried . Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Charles T. Canady . Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice ABOUT WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME & KIOSK Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee 2020 FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME INDUCTIONS Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee HONORING: Alice Scott Abbott . Accepted by Kim Medley Alma Lee Loy . Accepted by Robyn Guy E. Thelma Waters . Accepted by E. Thelma Waters CLOSING REMARKS Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women 2020 Commissioners Maruchi Azorin, M.B.A., Tampa Rita M. Barreto, Palm Beach Gardens Melanie Parrish Bonanno, Dover Madelyn E. Butler, M.D., Tampa Jennifer Houghton Canady, Lakeland Anne Corcoran, Tampa Lori Day, St. Johns Denise Dell-Powell, Orlando Sophia Eccleston, Wellington Candace D. Falsetto, Coral Gables Rep. Heather Fitzenhagen, Ft. Myers Senator Gayle Harrell, Stuart Karin Hoffman, Lighthouse Point Carol Schubert Kuntz, Winter Park Wenda Lewis, Gainesville Roxey Nelson, St. Petersburg Rosie Paulsen, Tampa Cara C. Perry, Palm City Rep. Jenna Persons, Ft. Myers Rachel Saunders Plakon, Lake Mary Marilyn Stout, Cape Coral Lady Dhyana Ziegler, DCJ, Ph.D., Tallahassee Commission Staff Kelly S. Sciba, APR, Executive Director Rebecca Lynn, Public Information and Events Coordinator Kimberly S.