The Copyrightability of Fictional Characters: Why Harry Potter, Arya Stark, and Matrim Cauthon Are Copyrightable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mhysa Or Monster: Masculinization, Mimicry, and the White Savior in a Song of Ice and Fire

Mhysa or Monster: Masculinization, Mimicry, and the White Savior in A Song of Ice and Fire by Rachel Hartnett A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2016 Copyright 2016 by Rachel Hartnett ii Acknowledgements Foremost, I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to my advisor Dr. Elizabeth Swanstrom for her motivation, support, and knowledge. Besides encouraging me to pursue graduate school, she has been a pillar of support both intellectually and emotionally throughout all of my studies. I could never fully express my appreciation, but I owe her my eternal gratitude and couldn’t have asked for a better advisor and mentor. I also would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Dr. Eric Berlatsky and Dr. Carol McGuirk, for their inspiration, insightful comments, and willingness to edit my work. I also thank all of my fellow English graduate students at FAU, but in particular: Jenn Murray and Advitiya Sachdev, for the motivating discussions, the all-nighters before paper deadlines, and all the fun we have had in these few years. I’m also sincerely grateful for my long-time personal friends, Courtney McArthur and Phyllis Klarmann, who put up with my rants, listened to sections of my thesis over and over again, and helped me survive through the entire process. Their emotional support and mental care helped me stay focused on my graduate study despite numerous setbacks. Last but not the least, I would like to express my heart-felt gratitude to my sisters, Kelly and Jamie, and my mother. -

El Ecosistema Narrativo Transmedia De Canción De Hielo Y Fuego”

UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE VALÈNCIA ESCOLA POLITE CNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Grado en Comunicación Audiovisual “El ecosistema narrativo transmedia de Canción de Hielo y Fuego” TRABAJO FINAL DE GRADO Autor/a: Jaume Mora Ribera Tutor/a: Nadia Alonso López Raúl Terol Bolinches GANDIA, 2019 1 Resumen Sagas como Star Wars o Pokémon son mundialmente conocidas. Esta popularidad no es solo cuestión de extensión sino también de edad. Niñas/os, jóvenes y adultas/os han podido conocer estos mundos gracias a la diversidad de medios que acaparan. Sin embargo, esta diversidad mediática no consiste en una adaptación. Cada una de estas obras amplia el universo que se dio a conocer en un primer momento con otra historia. Este conjunto de historias en diversos medios ofrece una narrativa fragmentada que ayuda a conocer y sumergirse de lleno en el universo narrativo. Pero a su vez cada una de las historias no precisa de las demás para llegar al usuario. El mundo narrativo resultante también es atractivo para otros usuarios que toman parte de mismo creando sus propias aportaciones. A esto se le conoce como narrativa transmedia y lleva siendo objeto de estudio desde principios de siglo. Este trabajo consiste en el estudio de caso transmedia de Canción de Hielo y Fuego la saga de novelas que posteriormente se adaptó a la televisión como Juego de Tronos y que ha sido causa de un fenómeno fan durante la presente década. Palabras clave: Canción de Hielo y Fuego, Juego de Tronos, fenómeno fan, transmedia, narrativa Summary Star Wars or Pokémon are worldwide knowledge sagas. This popularity not just spreads all over the world but also over an age. -

Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones

Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Gloria Makjanić Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Zadar, 2018. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Gloria Makjanić dr. sc. Zlatko Bukač Zadar, 2018. Makjanić 1 Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Gloria Makjanić, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Female Archetypes of Game of Thrones rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. Zadar, 13. rujna 2018. Makjanić 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. Game of Thrones ............................................................................................................. 4 3. Archetypes ...................................................................................................................... -

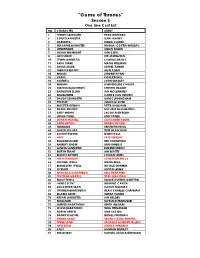

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Untitled Spreadsheet

Priority sector for Name of the project in Summary of the project in English, including goal and results (up Full name of the applicant Total project budget Requested amount ID Competition program LOT Type of project culture and arts English to 100 words) organization in English (in UAH) from UCF (in UAH) The television program is based on facts taken from historical sources, which testify to a fundamental distortion of the history of the Russian Empire, aimed at creating a historical mythology that Muscovy and Kievan Rus have common historical roots, that Muscovy has "inheritance rights" on Kievan Rus. The ordinary fraud of the Muscovites, who had taken possession of the past of The cycle of science- the Grand Duchy of Kiev and its people, dealt a terrible cognitive television blow to the Ukrainian ethnic group. Our task is to expose programs "UKRAINE. the falsehood and immorality of Moscow mythology on Union of STATE HISTORY. Part the basis of true facts. Without a great past, it is impossible Cinematographers "Film 3AVS11-0069 Audiovisual Arts LOT 1 TV content Individual Audiovisual Arts I." Kievan Rus " to create a great nation. Logos" 1369589 1369589 New eight 15-minute programs of the cycle “Game of Fate” are continuation of the project about outstanding historical figures of Ukrainian culture, art and science. The project consists of stories of the epistolary genre and memoirs. Private world of talented personalities, complex and ambiguous, is at the heart of the stories. These are facts from biographies that are not written in textbooks, encyclopedias, or wikipedia, but which are much more likely to attract the attention of different audiences. -

The Art of the Episode - Beginning of the Fifth Act

The art of the episode - beginning of the fifth act. The eighth and final season of Game of Thrones has begun. As a reminder: Dramaturgically speaking, this series is rather a long epic feature film and follows the corresponding rules. This structural structure is complemented by a historical drama in the tradition of Shakespeare. Therefore, Game of Thrones doesn't follow the rules of a series in which each episode must have a dramatic climax on the vertical narrative level. With this series of weekly comments on this series I complete the book "Game of Thrones sehen", published in 2017. With this eighth season the fifth act begins. Accordingly, the art of the first episode of this last season is not only to recall important aspects of the previous action after the long production and waiting period, but also to organize the necessary explicit action for the decisive fifth act. References to previous events must be included, especially to those of the first act, in this case the first and second season, which corresponds to the dramaturgical requirements of a last act of a feature film. This referential level is already established in the first scene when we observe a boy (Felix Jamieson) walking through the crowd to climb a tree to better observe the approaching troops. This scene reflects on the one hand the scene from the first season, in which Bran spotted the approaching caravan of King Robert from the lookout at Winterfell Castle. The boy's about the same age as Bran was in the first season. -

Game of Thrones V1

GAME OF THRONES THE OPEN WEB’S PICK FOR THE THRONE Winter is coming. The 8th and final season of Game of Thrones is right around the corner. While we can’t predict who will be decapitated next, we can analyze who you’re reading about. 65M page views later—read by +30M readers during the 7th season—we’ve got the results. WE ANALYZED +30M +7K +65M +80M Readers Articles Page Views Mins. Reading NUMBER OF READERS YOUR PICK FOR THE THRONE With so many contenders, you found Daenerys Targaryen and Jon Snow to be your favorites. Daenerys Targaryen Jon Snow Tyrion Lannister Cersei Lannister Jaime Lannister Arya Stark Bran Stark Sansa Stark Robert Baratheon Petyr “Littlefinger” Baelish 5M 10M 15M Daenerys Targaryen (AKA Khaleesi) and Jon Snow The Lannister family, allegedly the bad guys, are have almost twice the readers the Lannister family has, far more read about than the Starks. coming right after. Despite the threat he imposes in the series, the Night King isn’t as popular on the open web. MOST FAN INTEREST ON THE WESTEROS MAP We pinned all the main locations on the Westeros map to see which one has the highest number of readers. Almost all of Westeros’ cities attracted many readers, regardless of their size or the number of characters that come from there. +700K The Wall +1.5M Winterfell +50K Pyke +10K +1M +100K Casterly Rock Riverrun The Eyrie +2M King’s Landing +0.5M Highgarden King’s Landing takes the readership throne, as it’s where the Iron Throne sits, with over 2M readers. -

PHED Committee in January

PHED ITEM #3 January 25, 2021 Worksession M E M O R A N D U M January 20, 2021 TO: Planning, Housing, and Economic Development (PHED) Committee FROM: Gene Smith, Legislative Analyst SUBJECT: Review of Pandemic-related Business Assistance Programs PURPOSE: Discussion, no votes expected Those expected for this worksession: Jerome Fletcher, Office of the County Executive Laurie Boyer, Office of the County Executive Ben Wu, Montgomery County Economic Development Corporation (MCEDC) Bill Tompkins, MCEDC Sarah Miller, MCEDC The PHED committee requested a review of all the business assistance programs implemented by the County in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Program implementation was divided between the County and the MCEDC. I. Background and Summary The COVID-19 pandemic has created an uneven recession with certain industry sectors more impacted than others. Hospitality, leisure, restaurants, and retail businesses have seen the largest decline in economic activity. Much of this decline is due to the State and County health orders that restrict gathering size to limit the spread of the virus. While there was some expectation that the health orders and restrictions would be short-term measures, the reality is the pandemic has required that these orders remain in place for many months. The Council created many new business assistance programs for the impacted industry sectors to respond to this uneven recession. These new programs were funded and administered by the County or its partners. This memo provides a summary for each program implemented and includes detailed program information in the attachments. Table 1 provides an overview of all the programs included in this report. -

'Iron Throne' with a Noncompete? by Emily Wajert (May 16, 2019, 6:01 PM EDT)

Portfolio Media. Inc. | 111 West 19th Street, 5th Floor | New York, NY 10011 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Claiming The 'Iron Throne' With A Noncompete? By Emily Wajert (May 16, 2019, 6:01 PM EDT) I can’t seem to take off my employment lawyer hat, even when watching my favorite shows. True to form, the final season of “Game of Thrones” has been filled with twists and turns, battles and heroics, and, of course, alliances and betrayals. With the highly anticipated series finale set to premiere this weekend, one burning question remains[1] — who will end up on the Iron Throne? Over the course of the show’s eight seasons, there have been many worthy (and not-so-worthy) contenders. Up until recently, it seemed the character with the strongest claim to rule Westeros was Daenerys Stormborn of the House Targaryen, the First of Her Name, the Unburnt, Queen of the Andals, the Rhoynar and the First Emily Wajert Men, Queen of Meereen, Khaleesi of the Great Grass Sea, Protector of the Realm, Breaker of Chains and Mother of Dragons (aka Dany). However, Dany’s claim came under threat once characters learned that the honorable Jon Snow actually had an even stronger claim. (For those unfamiliar, Jon Snow recently learned his true identity, which arguably places him ahead of Dany in the line of succession for the throne). Even after learning of his true identity and potentially stronger claim to the throne, Jon Snow continued to swear his allegiance to Dany as his “Queen.” Despite these assurances, Dany was clearly distraught over the idea of a popular Jon Snow competing against her for the throne. -

Narrative Structure of a Song of Ice and Fire Creates a Fictional World

Narrative structure of A Song of Ice and Fire creates a fictional world with realistic measures of social complexity Thomas Gessey-Jonesa , Colm Connaughtonb,c , Robin Dunbard , Ralph Kennae,f,1 ,Padraig´ MacCarrong,h, Cathal O’Conchobhaire , and Joseph Yosee,f aFitzwilliam College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0DG, United Kingdom; bMathematics Institute, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom; cLondon Mathematical Laboratory, London W6 8RH, United Kingdom; dDepartment of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, e f 4 Oxford OX2 6GG, United Kingdom; Centre for Fluid and Complex Systems, Coventry University, Coventry CV1 5FB, United Kingdom; L Collaboration, Institute for Condensed Matter Physics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 79011 Lviv, Ukraine; gMathematics Applications Consortium for Science and Industry, Department of Mathematics & Statistics, University of Limerick, Limerick V94 T9PX, Ireland; and hCentre for Social Issues Research, University of Limerick, Limerick V94 T9PX, Ireland Edited by Kenneth W. Wachter, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved September 15, 2020 (received for review April 6, 2020) Network science and data analytics are used to quantify static and Schklovsky and Propp (11) and developed by Metz, Chatman, dynamic structures in George R. R. Martin’s epic novels, A Song of Genette, and others (12–14). Ice and Fire, works noted for their scale and complexity. By track- Graph theory has been used to compare character networks ing the network of character interactions as the story unfolds, it to real social networks (15) in mythological (16), Shakespearean is found that structural properties remain approximately stable (17), and fictional literature (18). To investigate the success of Ice and comparable to real-world social networks. -

“I'm All That Stands Between Them and Chaos:” a Monstrous Way of Ruling In

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00562-3 OPEN “I’m all that stands between them and chaos:” a monstrous way of ruling in A Song of Ice and Fire ✉ Györgyi Kovács 1 The article explores Tyrion Lannister’s rule in King’s Landing in the second volume of A Song of Ice and Fire books, A Clash of Kings. In the reception of ASOIAF and the TV show Game of Thrones, Tyrion was considered one of the best rulers, and the TV show ended by making him 1234567890():,; Hand to a king who delegated the greatest part of ruling to him. The analysis is based on Foucault’s notion of monstrosity in power, which is characterized by a monstrous conduct and includes the excess and potential abuse of power. The article argues that monstrosity in his rule reveals deeper layers in Tyrion’s personality, which is initially suggested to be defined by morality. The article also comes to the conclusion that his morality limits the scope of his monstrous methods, which eventually leads to his fall from power. ✉ 1 Eötvös Loránd University, Faculty of Humanities, Budapest, Hungary. email: [email protected] HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2020) 7:70 | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00562-3 1 ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00562-3 Introduction ne of the most compelling features of George R. R. of his character and anticipates that in the books Tyrion will turn OMartin’s A Song of Ice and Fire (ASOIAF) books is the a villain motivated by vengeance (Bryndenbfish, 2019), which is way they present a richly detailed medieval fantasy world exactly the opposite of how his storyline ended in the TV show. -

A Game of Thrones a Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

A Game of Thrones A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin Book One: A Game of Thrones Book Two: A Clash of Kings Book Three: A Storm of Swords Book Four: A Feast for Crows Book Five: A Dance with Dragons Book Six: The Winds of Winter (being written) Book Seven: A Dream of Spring “ Fire – Dragons, Targaryens Lord of Light Ice – Winter, Starks, the Wall White Walkers Spoilers!! Humans as meaning-makers – Jerome Bruner Humans as story-tellers – narrative theory Humans as mythopoeic–Carl G. Jung, Joseph Campbell The mythic themes in A Song of Ice and Fire are ancient Carl Jung: Archetypes are powerful & primordial images & symbols Collective unconscious Carl Jung’s archetypes Great Mother; Father; Hero; Savior… Joseph Campbell – The Power of Myth The Hero’s Journey Carole Pearson – the 12 archetypes Ego stage: Innocent; Orphan; Caretaker; Warrior Soul transformation: Seeker; Destroyer; Lover; Creator; Self: Ruler; Magician; Sage; Fool Maureen Murdock – The Heroine’s Journey The Great Mother (& Maiden, & Crone), the Great Father, the child, the Shadow, the wise old man, the trickster, the hero…. In the mystery of the cycle of seasons In ancient gods & goddesses In myth, fairy tale & fantasy & the Seven in A Game of Thrones The Gods: The Old Gods The Seven (Norse mythology): Maiden, Mother, Crone Father, Warrior, Smith Stranger (neither male or female) R’hilor (Lord of light) Others: The Drowned God, Mother Rhoyne The family sigils Stark - Direwolf Baratheon – Stag Lannister – Lion Targaryen