Non-Conforming Femininity in Game of Thrones: an Analysis of Arya Stark and Brienne of Tarth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hbo Premieres the Third Season of Game of Thrones

HBO PREMIERES THE THIRD SEASON OF GAME OF THRONES The new season will premiere simultaneously with the United States on March 31st Miami, FL, March 18, 2013 – The battle for the Iron Throne among the families who rule the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros continues in the third season of the HBO original series, Game of Thrones. Winner of two Emmys® 2011 and six Golden Globes® 2012, the series is based on the famous fantasy books “A Song of Ice and Fire” by George R.R. Martin. HBO Latin America will premiere the third season simultaneously with the United States on March 31st. Many of the events that occurred in the first two seasons will culminate violently, with several of the main characters confronting their destinies. But new challengers for the Iron Throne rise from the most unexpected places. Characters old and new must navigate the demands of family, honor, ambition, love and – above all – survival, as the Westeros civil war rages into autumn. The Lannisters hold absolute dominion over King’s Landing after repelling Stannis Baratheon’s forces, yet Robb Stark –King of the North– still controls much of the South, having yet to lose a battle. In the Far North, Mance Rayder (new character portrayed by Ciaran Hinds) has united the wildlings into the largest army Westeros has ever seen. Only the Night’s Watch stands between him and the Seven Kingdoms. Across the Narrow Sea, Daenerys Targaryen – reunited with her three growing dragons – ventures into Slaver’s Bay in search of ships to take her home and allies to conquer it. -

GAME of THRONES® the Follow Tours Include Guides with Special Interest and a Passion for the Game of Thrones

GAME OF THRONES® The follow tours include guides with special interest and a passion for the Game of Thrones. However you can follow the route to explore the places featured in the series. Meet your Game of Thrones Tours Guide Adrian has been a tour guide for many years, with a passion for Game of Thrones®. During filming he was an extra in various scenes throughout the series, most noticeably, a stand in double for Ser Davos. He is also clearly seen guarding Littlefinger before his final demise at the hands of the Stark sisters in Winterfell. Adrian will be able to bring his passion alive through his experience, as well as his love of Northern Ireland. Cairncastle ~ The Neck & North of Winterfell 1 Photo stop of where Sansa learns of her marriage to Ramsay Bolton, and also where Ned beheads Will, the Night’s Watch deserter. Cairncastle Refreshment stop at Ballygally Castle, Ballygally Located on the scenic Antrim coast facing the soft, sandy beaches of Ballygally Bay. The Castle dates back to 1625 and is unique in that it is the only 17th Century building still used as a residence in Northern Ireland today. The hotel is reputedly haunted by a friendly ghost and brave guests can visit the ‘ghost room’ in one of the towers to see for themselves. View Door No. 9 of the Doors of Thrones and collect your first stamp in your Journey of Doors passport! In the hotel foyer you will be able to admire the display cabinets of the amazing Steensons Game of Thrones® inspired jewellery. -

Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones

Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Gloria Makjanić Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Zadar, 2018. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Gloria Makjanić dr. sc. Zlatko Bukač Zadar, 2018. Makjanić 1 Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Gloria Makjanić, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Female Archetypes of Game of Thrones rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. Zadar, 13. rujna 2018. Makjanić 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. Game of Thrones ............................................................................................................. 4 3. Archetypes ...................................................................................................................... -

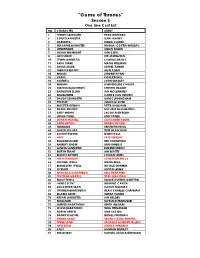

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

William Hope Hodgson's Borderlands

William Hope Hodgson’s borderlands: monstrosity, other worlds, and the future at the fin de siècle Emily Ruth Alder A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 © Emily Alder 2009 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter One. Hodgson’s life and career 13 Chapter Two. Hodgson, the Gothic, and the Victorian fin de siècle: literary 43 and cultural contexts Chapter Three. ‘The borderland of some unthought of region’: The House 78 on the Borderland, The Night Land, spiritualism, the occult, and other worlds Chapter Four. Spectre shallops and living shadows: The Ghost Pirates, 113 other states of existence, and legends of the phantom ship Chapter Five. Evolving monsters: conditions of monstrosity in The Night 146 Land and The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’ Chapter Six. Living beyond the end: entropy, evolution, and the death of 191 the sun in The House on the Borderland and The Night Land Chapter Seven. Borderlands of the future: physical and spiritual menace and 224 promise in The Night Land Conclusion 267 Appendices Appendix 1: Hodgson’s early short story publications in the popular press 273 Appendix 2: Selected list of major book editions 279 Appendix 3: Chronology of Hodgson’s life 280 Appendix 4: Suggested map of the Night Land 281 List of works cited 282 © Emily Alder 2009 2 Acknowledgements I sincerely wish to thank Dr Linda Dryden, a constant source of encouragement, knowledge and expertise, for her belief and guidance and for luring me into postgraduate research in the first place. -

Game of Thrones V1

GAME OF THRONES THE OPEN WEB’S PICK FOR THE THRONE Winter is coming. The 8th and final season of Game of Thrones is right around the corner. While we can’t predict who will be decapitated next, we can analyze who you’re reading about. 65M page views later—read by +30M readers during the 7th season—we’ve got the results. WE ANALYZED +30M +7K +65M +80M Readers Articles Page Views Mins. Reading NUMBER OF READERS YOUR PICK FOR THE THRONE With so many contenders, you found Daenerys Targaryen and Jon Snow to be your favorites. Daenerys Targaryen Jon Snow Tyrion Lannister Cersei Lannister Jaime Lannister Arya Stark Bran Stark Sansa Stark Robert Baratheon Petyr “Littlefinger” Baelish 5M 10M 15M Daenerys Targaryen (AKA Khaleesi) and Jon Snow The Lannister family, allegedly the bad guys, are have almost twice the readers the Lannister family has, far more read about than the Starks. coming right after. Despite the threat he imposes in the series, the Night King isn’t as popular on the open web. MOST FAN INTEREST ON THE WESTEROS MAP We pinned all the main locations on the Westeros map to see which one has the highest number of readers. Almost all of Westeros’ cities attracted many readers, regardless of their size or the number of characters that come from there. +700K The Wall +1.5M Winterfell +50K Pyke +10K +1M +100K Casterly Rock Riverrun The Eyrie +2M King’s Landing +0.5M Highgarden King’s Landing takes the readership throne, as it’s where the Iron Throne sits, with over 2M readers. -

Download 1St Season of Game of Thrones Free Game of Thrones, Season 1

download 1st season of game of thrones free Game of Thrones, Season 1. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. The PlayOn Blog. Record All 8 Seasons Game of Thrones | List of Game of Thrones Episodes And Running Times. Here at PlayOn, we thought. wouldn't it be great if we made it easy for you to download the Game of Thrones series to your iPad, tablet, or computer so you can do a whole lot of binge watching? With the PlayOn Cloud streaming DVR app on your phone or tablet and the Game of Thrones Recording Credits Pack , you'll be able to do just that, AND you can do it offline. That's right, offline . -

Narrative Structure of a Song of Ice and Fire Creates a Fictional World

Narrative structure of A Song of Ice and Fire creates a fictional world with realistic measures of social complexity Thomas Gessey-Jonesa , Colm Connaughtonb,c , Robin Dunbard , Ralph Kennae,f,1 ,Padraig´ MacCarrong,h, Cathal O’Conchobhaire , and Joseph Yosee,f aFitzwilliam College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0DG, United Kingdom; bMathematics Institute, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom; cLondon Mathematical Laboratory, London W6 8RH, United Kingdom; dDepartment of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, e f 4 Oxford OX2 6GG, United Kingdom; Centre for Fluid and Complex Systems, Coventry University, Coventry CV1 5FB, United Kingdom; L Collaboration, Institute for Condensed Matter Physics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 79011 Lviv, Ukraine; gMathematics Applications Consortium for Science and Industry, Department of Mathematics & Statistics, University of Limerick, Limerick V94 T9PX, Ireland; and hCentre for Social Issues Research, University of Limerick, Limerick V94 T9PX, Ireland Edited by Kenneth W. Wachter, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved September 15, 2020 (received for review April 6, 2020) Network science and data analytics are used to quantify static and Schklovsky and Propp (11) and developed by Metz, Chatman, dynamic structures in George R. R. Martin’s epic novels, A Song of Genette, and others (12–14). Ice and Fire, works noted for their scale and complexity. By track- Graph theory has been used to compare character networks ing the network of character interactions as the story unfolds, it to real social networks (15) in mythological (16), Shakespearean is found that structural properties remain approximately stable (17), and fictional literature (18). To investigate the success of Ice and comparable to real-world social networks. -

Cheat Sheet to Westeros and Beyond, Your Guide on Catching up to “Game of Thrones” Before Season 8 Starts April 14

“Game of Thrones” has several great battle scenes, and the sixth season features the Battle of the Bastards, one of the most epic battle scenes ever filmed, movie or television. COURTESY/HBO ith the final season of “Game of Thrones” fast approaching, you might feel a little left out of the pop culture phenomenon as ‘GAME OF your friends and family discuss Targaryens, Starks and Lan- nisters. But it’s not too late to get caught up, if you’re willing to Wtake a crash course in the Seven Realms. THRONES’ Today we’re giving you a cheat sheet to Westeros and beyond, your guide on catching up to “Game of Thrones” before Season 8 starts April 14. This is by no means complete. We definitely recommend you take time later to go back and watch the entire series, which is epic in scale and qual- TV ity. We’ve boiled the show’s 67 episodes down to 28, or a little over 26 hours ‘Game of CHEAT Thrones’ season of viewing. While you won’t get every detail, this list will give you what you 8 premiere need to understand the major plot points. With a bit of dedication, you can 8 p.m. April 14, HBO get through it all in a week. SHEET And if you’re already familiar with Game of Thrones, you can use this as a guide to re-familiarize yourself with the world you’ve been missing for the last 18 months. Your guide to catching up on the Seven Tip: Wikipedia has pretty good summaries for each episode. -

A Game of Thrones a Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

A Game of Thrones A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin Book One: A Game of Thrones Book Two: A Clash of Kings Book Three: A Storm of Swords Book Four: A Feast for Crows Book Five: A Dance with Dragons Book Six: The Winds of Winter (being written) Book Seven: A Dream of Spring “ Fire – Dragons, Targaryens Lord of Light Ice – Winter, Starks, the Wall White Walkers Spoilers!! Humans as meaning-makers – Jerome Bruner Humans as story-tellers – narrative theory Humans as mythopoeic–Carl G. Jung, Joseph Campbell The mythic themes in A Song of Ice and Fire are ancient Carl Jung: Archetypes are powerful & primordial images & symbols Collective unconscious Carl Jung’s archetypes Great Mother; Father; Hero; Savior… Joseph Campbell – The Power of Myth The Hero’s Journey Carole Pearson – the 12 archetypes Ego stage: Innocent; Orphan; Caretaker; Warrior Soul transformation: Seeker; Destroyer; Lover; Creator; Self: Ruler; Magician; Sage; Fool Maureen Murdock – The Heroine’s Journey The Great Mother (& Maiden, & Crone), the Great Father, the child, the Shadow, the wise old man, the trickster, the hero…. In the mystery of the cycle of seasons In ancient gods & goddesses In myth, fairy tale & fantasy & the Seven in A Game of Thrones The Gods: The Old Gods The Seven (Norse mythology): Maiden, Mother, Crone Father, Warrior, Smith Stranger (neither male or female) R’hilor (Lord of light) Others: The Drowned God, Mother Rhoyne The family sigils Stark - Direwolf Baratheon – Stag Lannister – Lion Targaryen -

Mariana Lima Terres FEMININE POWER in the HBO TV SERIES GAME of THRONES: the CASE of DAENERYS TARGARYEN

Mariana Lima Terres FEMININE POWER IN THE HBO TV SERIES GAME OF THRONES: THE CASE OF DAENERYS TARGARYEN Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Inglês: Estudos Linguísticos e Literários da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para a obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Inglês. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Viviane M. Heberle FLORIANÓPOLIS 2019 Mariana Lima Terres FEMININE POWER IN THE HBO TV SERIES GAME OF THRONES: THE CASE OF DAENERYS TARGARYEN Esta Dissertação foi julgada adequada para obtenção do Título de “Mestre” e aprovada em sua forma final pelo Programa de Pós Graduação em Inglês: Estudos Linguísticos e Literários. Florianópolis, 27 de fevereiro de 2019. ________________________ Prof. Dr. Celso H. Soufen Tumolo Coordenador do Curso Banca Examinadora: ________________________ Prof.ª Dr.ª Viviane M. Heberle Orientadora Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina ________________________ Prof.ª Dr.ª Susana Bornéo Funck Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina ________________________ Profª. Drª. Renata Kabke Pinheiro Universidade Federal de Pelotas – via interação virtual This is dedicated to my family and friends. ACNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank my family, friends and those who helped me going through this incredible journey, which is to produce a Master thesis; for all the support in moments of doubt and anxiety you gave me; for sharing so many moments of happiness and joy during these two years. I know that this would not have happened if I did not have you by my side. Thank you mother and father, Sonia and Ubirajara, for your unconditionally love and help. Thank you dear sisters, Gabriela and Alanna, who gave me strength and persistence all the way. -

Love Enthroned

Love Enthroned Author(s): Steele, Daniel (1824-1914) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Daniel Steele firmly agreed with John Wesley that Christians can and should live a life free of voluntary sin. This striving towards perfection of faith became known as the ªHoliness Movement.º Originally a Methodist/Wesleyan phenomenon, the movement came to have profound effects on later Pentecostal and evangelical Christian communities. This work lays out the doctrine of sanctification, and urges readers to seek further sanctification in everyday life. Because Steele shares his own personal testimony of his faith, the book takes on a decidedly more intimate and relatable nature. Kathleen O'Bannon CCEL Staff Subjects: Doctrinal theology Salvation i Contents Title Page 1 Chapter 1. Love Revealed. 2 Chapter 2. Love Militant. 5 Chapter 3. Love Triumphant Over Original Sin 11 Chapter 4. Full Salvation Immediately Attainable 14 Chapter 5. Bible Texts For Sin Examined 20 Chapter 6. Deliverance Deferred 24 Chapter 7. Metaphorical Representations of Perfect Love 28 Chapter 8. St. Paul's Great Prayer of the Higher Life 40 Chapter 9. The Three Dispensations 47 Chapter 10. Perfect Love as a Definite Blessing 54 Chapter 11. The Fruits of Perfect Love 57 Chapter 12. Salvation From Artificial Appetites 67 Chapter 13. The Full Assurance of Faith 72 Chapter 14. The Evidences of Perfect Love 88 Chapter 15. Testimony 95 Chapter 16. Spiritual Dynamics 109 Chapter 17. Stumbling-Blocks in the King's Highway 114 Chapter 18. Growth in Grace 119 Chapter 19. Objections Answered. 122 Chapter 20. An Address to the Young Convert--the Higher Path 127 Chapter 21.