Temples, Courts, and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Indian Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

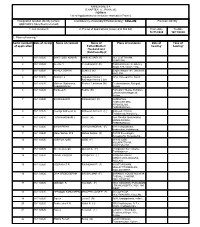

(CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for Inclusion

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): KOLLAM Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 SANTHOSH KUMAR MANI ACHARI (F) 163, CHITTAYAM, PANAYAM, , 2 16/11/2020 Geethu Y Yesodharan N (F) Padickal Rohini, Residency Nagar 129, Kollam East, , 3 16/11/2020 AKHILA GOPAN SUMA S (M) Sagara Nagar-161, Uliyakovil, KOLLAM, , 4 16/11/2020 Akshay r s Rajeswari Amma L 1655, Kureepuzha, kollam, , Rajeswari Amma L (M) 5 16/11/2020 Mahesh Vijayamma Reshmi S krishnan (W) Devanandanam, Mangad, Gopalakrishnan Kollam, , 6 16/11/2020 Sandeep S Rekha (M) Pothedath Thekke Kettidam, Lekshamana Nagar 29, Kollam, , 7 16/11/2020 SIVADASAN R RAGHAVAN (F) KANDATHIL THIRUVATHIRA, PRAKKULAM, THRIKKARUVA, , 8 16/11/2020 Neeraja Satheesh G Satheesh Kumar K (F) Satheesh Bhavan, Thrikkaruva, Kanjavely, , 9 16/11/2020 LATHIKAKUMARI J SHAJI (H) 184/ THARA BHAVANAM, MANALIKKADA, THRIKKARUVA, , 10 16/11/2020 SHIVA PRIYA JAYACHANDRAN (F) 6/113 valiyazhikam, thekkecheri, thrikkaruva, , 11 16/11/2020 Manu Sankar M S Mohan Sankar (F) 7/2199 Sreerangam, Kureepuzha, Kureepuzha, , 12 16/11/2020 JOSHILA JOSE JOSE (F) 21/832 JOSE VILLAKATTUVIA, -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

In the High Court of Kerala at Ernakulam

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM PRESENT THE HONOURABLE MR.JUSTICE BECHU KURIAN THOMAS TUESDAY, THE 28TH DAY OF APRIL, 2020/8TH VAISAKHA, 1942 W.P(C) TMP NO.182 OF 2020 PETITIONERS: 1.KERALA VYDYUTHI MAZDOOR SANGHAM (BMS), I.S. PRESS ROAD, ERNAKULAM, KOCHI – 682 018. REPRESENTED BY ITS GENERAL SECRETARY GIREESH KULATHOOR, AGED 39 YEARS, S/O. K. CHANDRASEKHARAN NAIR, METER READER, K.S.E.B., UDIYANKULANGARA ELECTRICAL SECTION, THIRUVANATHAPURAM – 695 122; RESIDING AT MANGALYA, NALLOORVATTOM, PLAMOOTTUKADA, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM - 695 120) 2.P.S. MANOJ KUMAR, AGED 47 YEARS, S/O. SREEDHARAN NAIR, OVERSEER, K.S.E.B., ELECTRICAL SECTION, ALUVA TOWN, ERNAKULAM – 683 101; (RESIDING AT PARAMATTU HOUSE, V.K.C. P.O., KOCHI – 682 021) BY ADVOCATES SRI. DR. K.P. SATHEESAN (SR.), SRI. P. MOHANDAS, SRI. K. SUDHINKUMAR SRI. S.K. ADHITHYAN SRI.SABU PULLAN RESPONDENTS: 1.STATE OF KERALA, REPRESENTED BY THE CHIEF SECRETARY, GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 001. W.P(C) TMP NOS.182, 183, 184, 196 & 198 OF 2020 2 2. THE ADDITIONAL CHIEF SECRETARY (FINANCE), FINANCE DEPARTMENT, GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 001. R1-2 BY SRI. GOVERNMENT PLEADER SRI.K.P.HARISH THIS WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) TMP HAVING COME UP FOR ADMISSION ON 28.04.2020, ALONG WITH WPC.183, 184, 196 AND 198 OF 2020 THE COURT ON THE SAME DAY DELIVERED THE FOLLOWING: W.P(C) TMP NOS.182, 183, 184, 196 & 198 OF 2020 3 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM PRESENT THE HONOURABLE MR.JUSTICE BECHU KURIAN THOMAS TUESDAY, THE 28TH DAY OF APRIL, 2020/8TH VAISAKHA, 1942 W.P(C) TMP NO.183 OF 2020 PETITIONER: 1.AIDED HIGHER SECONDARY TEACHERS ASSOCIATION, REPRESENTED BY ITS GENERAL SECRETARY S. -

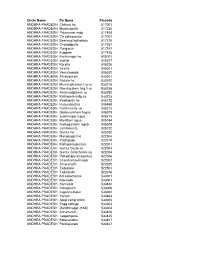

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958 (24 of 1958)

The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958 (24 of 1958) as amended by The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Amendment and Validation) Act, 2010(10 of 2010) CONTENTS THE ANCIENT MONUMENTS AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES AND REMAINS ACT, 1958 The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Amendment and Validation) Act, 2010 (10 of 2010) Introduction PRELIMINARY Sections 1. Short title, extent and commencement 2. Definitions 2A Construction of references to any law not in force in the State of Jammu and Kashmir ANCIENT MONUMENTS AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES AND REMAINS OF NATIONAL IMPORTANCE 3. Certain ancient monuments/ etc., deemed to be of national importance 4. Power of Central Government to declare ancient monument, etc., to be of national importance 4A Categorisation and classification in respect of ancient monuments or archaeological sites and remains declared as of national importance under sections 3 and 4 PROTECTED MONUMENTS 5. Acquisition of rights in a protected monument 6. Preservation of protected monument by agreement 7. Owners under disability or not in possession 8. Application of endowment to repair a protected monument 9. Failure or refusal to enter into an agreement 10. Power to make order prohibiting contravention of agreement under section 6 11. Enforcement of agreement 12. Purchasers at certain sales and persons claiming through owner bound by instrument executed by owner 13. Acquisition of protected monuments 14. Maintenance of certain protected monuments 15. Voluntary contributions 16. Protection of place of worship from misuse, pollution or desecration 17. Relinquishment of Government rights in a monument 18. Right of access to protected monument PROTECTED AREAS 19. -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

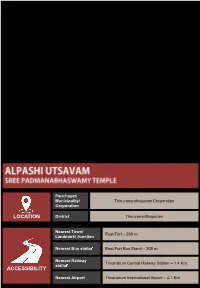

Location Accessibility

Panchayat/ Municipality/ Thiruvananthapuram Corporation Corporation LOCATION District Thiruvananthapuram Nearest Town/ East Fort – 200 m Landmark/ Junction Nearest Bus statio East Fort Bus Stand – 200 m Nearest Railway Trivandrum Central Railway Station – 1.4 Km statio ACCESSIBILITY Nearest Airport Trivandrum International Airport – 4.1 Km The Executive Officer Mathilakam Office, West Nada Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple East Fort, Thiruvananthapuram -695023 Phone: +91-471-2450233 +91-471-2466830 (Temple) CONTACT +91-471-2464606 (Helpline) Email: [email protected] Website: www.sreepadmanabhaswamytemple.org DATES FREQUENCY DURATION TIME October – November (Thulam) Annual 10 Days ABOUT THE FESTIVAL (Legend/History/Myth) The festival is a ritualistic and colourful celebration at the Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple. Ritualistic circumambulations in different kinds of vehicles called Vahanams are an important part of the festivities. In olden times, idols were carried by elephants, however, the practice was given up after an elephant ran amok. Now, a number of priests carry the idols in special Vahanams placed on their shoulders. Six kinds of vehicles are used for these processions. These are the Simhasana Vahanam (Throne), Anantha Vahanam (Serpent), Kamala Vahanam (Lotus), Pallakku Vahanam (Palanquin), Garuda Vahanam (Garuda) and Indra Vahanam (Gopuram). Of these , the Pallakku and Garuda Vahanas are repeated twice and four times respectively. The Garuda Vahanam is considered as the favourite conveyance of the Lord. The different days on which the Vahanams are taken out for procession are as follows: Simhasana Vahanam, Anantha Vahanam, Kamala Vahanam, Pallakku Vahanam, Garuda Vahanam, Indra Vahanam, Pallakku Vahanam and Garuda Vahanam on the following days. Sree Padmanabhaswamy’s Vahanam is in gold while Narayana Swamy’s and Sree Krishna Swamy’s Vahanas are in silver. -

Day Tour to Guruvayur Temple and Elephant Camp

DAY TOUR TO GURUVAYUR TEMPLE AND ELEPHANT CAMP Around 07:30 AM, pick up from respective hotels in Cochin and proceed to Guruvayur (Around 2 ½ hrs drive). Upon arrival visit Punnathur Elephant Court. Punnathurkotta was once the palace of a local ruler, but the palace grounds are now used to house the elephants belonging to the Guruvayoor temple, and has been renamed Anakkotta (meaning "Elephant Fort"). There were 86 elephants housed there, but currently there are about 59 elephants. The elephants are ritual offerings made by the devotees of Lord Guruvayurappa. This facility is also used to train the elephants to serve Lord Krishna as well as to participate in many festivals that occur throughout the year. The oldest elephant is around 82 years of age and is called 'Ramachandran'. Later visit the famous Guruvayur Temple. Guruvayur Sri Krishna Temple is a Hindu temple dedicated to the god Krishna (an avatar of the god Vishnu), located in the town of Guruvayur in Kerala, India. It is one of the most important places of worship for Hindus of Kerala and is often referred to as "Bhuloka Vaikunta" which translates to the "Holy Abode of Vishnu on Earth". Have lunch from Guruvayur and proceed back to conference venue. En route visit Kodungaloor. Once a maritime port of international repute because of its strategic location at the confluence of the Periyar River and the Arabian Sea, Kondugalloor was considered the gateway to ancient India or the Rome of the East, because of its status as a centre for trade. It was also the entry point of three major religions to India - Christianity, Judaism and Islam. -

The Role of Hindu Code Bill in Social Reconstruction of India (With Special Reference to Dr

P: ISSN NO.: 2394-0344 RNI No.UPBIL/2016/67980 VOL-2* ISSUE-10* January- 2018 E: ISSN NO.: 2455-0817 Remarking An Analisation The Role of Hindu Code Bill in Social Reconstruction of India (With Special Reference to Dr. B. R. Ambedkar) Abstract The Hindu Code Bill are the thoughts of such a social reformer who want to reforme the conditions of women making the important laws and regulations about Indian women. In this series Dr. B.R. Ambedkar proves himself such a thinker in India who thinks about reformation of Indian women legally. According to Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, “Women is a main piller of a family whose role is an important in a family i.e. she is first teacher of a child and to make a personality of a child, she has in the centre of a family. If a women in a family is literate, then she will try to literate her child in any condition and literacy is very essential for a civilized society as well as literacy is aware to a women for her rights in a society. Before this Bill, the conditions of Indian women were very miserable—she has no right to take education, no right to live free life, she always depend on her family members like a slave in society. So, the Hindu Code Bill was a step which tried to reform the conditions of Indian women and tried to give the rights of education, services, freedom and to live the life like a man. Pitamber Dass Jatav Keywords: Reforms, Hindu, Code, Bill, Assembly, Debates, Act, Women, Assistant Professor, Indian Society, Religion, Mitakshra, Tradition, Laws. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Dated 9Th October, 2018 Reg. Elevation

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA This file relates to the proposal for appointment of following seven Advocates, as Judges of the Kerala High Court: 1. Shri V.G.Arun, 2. Shri N. Nagaresh, 3. Shri P. Gopal, 4. Shri P.V.Kunhikrishnan, 5. Shri S. Ramesh, 6. Shri Viju Abraham, 7. Shri George Varghese. The above recommendation made by the then Chief Justice of the th Kerala High Court on 7 March, 2018, in consultation with his two senior- most colleagues, has the concurrence of the State Government of Kerala. In order to ascertain suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have consulted our colleagues conversant with the affairs of the Kerala High Court. Copies of letters of opinion of our consultee-colleagues received in this regard are placed below. For purpose of assessing merit and suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have carefully scrutinized the material placed in the file including the observations made by the Department of Justice therein. Apart from this, we invited all the above-named recommendees with a view to have an interaction with them. On the basis of interaction and having regard to all relevant factors, the Collegium is of the considered view that S/Shri (1) V.G.Arun, (2) N. Nagaresh, and (3) P.V.Kunhikrishnan, Advocates (mentioned at Sl. Nos. 1, 2 and 4 above) are suitable for being appointed as Judges of the Kerala High Court. As regards S/Shri S. Ramesh, Viju Abraham, and George Varghese, Advocates (mentioned at Sl.