Guerrillas in Our Midst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Tale of Two Cities - Walsh 76

A TALE OF TWO CITIES - WALSH 76. SCENE 19 (The scene shifts to the Manettes’ home in London. Lucie and Miss Pross enter. Lucie is upset. Miss Pross has to work hard to keep up.) MISS PROSS Miss Lucie! Miss Lucie! What on earth is wrong? LUCIE He has oppressed no man. He has imprisoned no man. Rather than harshly exacting payment of his dues, he relinquished them of his own free will. He left instructions to his steward to give the people what little there was to give. And for this service, he is to be imprisoned. MISS PROSS What are you talking about, Miss Lucie? LUCIE The decree. MISS PROSS What decree? There have been so many decrees I’ve lost count. LUCIE They are arresting emigrants. (The doorbell rings.) MISS PROSS But you remember what Mister Carton said, how unreliable the news is from France during these troubled times. LUCIE I must go to him. MISS PROSS You what? LUCIE If I leave now, there is a chance I may overtake him before he arrives in Paris. (Carton enters.) MISS PROSS Oh, Mister Carton! Thank goodness. Do talk some sense into her. A TALE OF TWO CITIES - WALSH 77. CARTON I, Miss Pross? When have I ever been known to talk sense? MISS PROSS She’s got it in her head to go to Paris! CARTON She... what? Lucie, you can’t be serious. LUCIE I am quite serious. Charles would do no less if our positions were reversed. CARTON Charles would not have let you go to Paris in the first place. -

Growing a Commons Food Regime: Theory and Practice

Growing a Commons Food Regime: Theory and Practice Thesis Submitted to University College London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Marina Chang Development Planning Unit The Bartlett, Faculty of the Built Environment University College London 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Marina Chang, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract Existing food regimes theory has a strong analytical power to help us understand the reality of contemporary global food politics and has a political commitment to provoke a new direction in our thinking. Yet, it falls short on how we can actually engage with such a change, especially with the pressing need for strategic alliances among multiple food movements which aim to advance a regime change. By exploring both theory and practice, this research addresses this gap and responds to a call for a new food regime in the 21st century. Firstly, this research proposes the notion of growing a commons food regime. With care as the core, an integrative framework for growing a commons food regime is presented, drawing on reviews of literature on food regimes theory, commons regimes, adaptive governance and critical food studies. This framework aims at building an adaptive capacity to transform the current food system towards sustainability. Secondly, applying the framework as ‘a tool of insight’, the current landscape of community food initiatives was investigated in order to identify implications and opportunities to grow a commons food regime in London. Finally, considering the significant role of universities in helping to form multiple and reciprocal connections with society; and as a catalyst and an experiment in integrating theory and practice in growing a commons food regime, a journey of university-led community food initiatives was carried out at University College London (UCL) as a case study. -

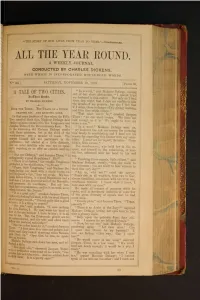

All the Year Round. a Weekly Journal

"THE STORY OF OUR LIVES FROM YEAR TO YEAR."---SHAKEsPEArE. ALL THE YEAR ROUND. A WEEKLY JOURNAL. CONDUCTED BY CHARLES DICKENS. WITH WHICH IS INCORPORATED HOUSEHOLD WORDS. SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 1859. N°- 30.] [PRICE 2d. "In a word," said Madame Defarge, coming A TALE OF TWO CITIES. out of her short abstraction, "I cannot trust In Three Books. my husband in this matter. Not only do I feel By CHARLES DICKENS. since last night, that I dare not confide to him the details of my projects; but also I feel that if I delay, there is danger of his giving warning, BOOK THE THIRD. THE TRACK OF A STORM. and then they might escape." CHAPTER XIV. THE KNITTING DONE. "That must never be," croaked Jacques IN that same juncture of time when the Fifty- Three; "no one must escape. We have not Two awaited their fate, Madame Defarge held half enough as it is. We ought to have six darkly ominous council with The Vengeance and score a day." Jacques Three of the Revolutionary Jury. Not "In a word," Madame Defarge went on, in the wine-shop did Madame Defarge confer "my husband has not my reason for pursuing with these ministers, but in the shed of the this family to annihilation, and I have not his wood-sawyer, erst a mender of roads. The reason for regarding this Doctor with any sensi- sawyer himself did not participate in the bility. I must act for myself, therefore. Come conference, but abided at a little distance, hither, little citizen." like an outer satellite who was not to speak The wood-sawyer, who held her in the re- until required, or to offer an opinion until in- spect, and himself in the submission, of mor- vited. -

Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens A Tale of Two Cities (1859) It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, Intro Horner it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness… Spring ‘ 06 This piece of fiction is based on many actual historical events. The Plot The action of A Tale of Two Cities takes place over a period of about eighteen years, beginning in 1775, and ending in 1793. Some of the story takes place earlier, as told in the flashbacks. It centers around the years leading up to French Revolution and culminates in the Jacobin Reign of Terror. It tells the story of two men, Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton, who look very alike but are entirely different in character. Darnay is a romantic descended from French aristocrats, while Carton is a cynical English barrister. The two are in love with the same woman, Lucie Manette: one will love her from afar and make a courageous sacrifice for her and the other will marry her. Lucie Manette Charles Darnay Sydney Carton In France after more than seventeen years of unjust imprisonment, Dr. Alexandre Manette (Lucie’s father) is released from the infamous Bastille, setting into motion this time spanning story of revenge and resurrection. Upon his release, Manette is sheltered and cared for by an old servant, Ernest Defarge, the wine vendor and his wife Madame Defarge. Madame Defarge The Setting London, England Paris, France Conflict In his dual focus on the French Revolution and the individual lives of his characters, Dickens draws many comparisons between the historical developments taking place and the characters’ triumphs and travails. -

A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities CHARLES DICKENS A Tale of Two Cities is set before and during the French Revolution, and examines the harsh con- 1859 ditions and brutal realities of life during this difficult time. While the conditions before the revolution were deplorable, things were far from ideal afterward as the violence toward, and oppression of, one class was reversed once the poor overthrew the nobility. In the end, the only glimmer of hope comes with the heroic sacrifice of Sydney Carton, as he gives his life for the good of others. According to Dickens’s Preface, the inspira- tion for the story came from two sources. The first was Wilkie Collins’s play The Frozen Deep, in which two rivals unknowingly embark on the same doomed Arctic expedition, and one ends up dying to save his rival. The second was Thomas Carlyle’s The French Revolution: A History. The details in the portions of A Tale of Two Cities that take place in France closely echo Carlyle’s work, and critics have noted that Carlyle’s account seems to be Dickens’s only source of historical information. One of the most-discussed aspects of A Tale of Two Cities is the ambivalence with which Dickens seems to regard the revolution and the revolutionaries. Although he clearly under- stands why the French people rose up to over- throw their government and seize power for themselves, he seems troubled by the manner in which this occurred. The violence and brutality 494 ATaleofTwoCities THE NEW ERA BEGAN; THE KING WAS TRIED, DOOMED, AND BEHEADED; THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY, OR DEATH, DECLARED FOR BIOGRAPHY VICTORY OR DEATH AGAINST THE WORLD IN ARMS; THE Charles Dickens BLACK FLAG WAVED NIGHT AND DAY FROM THE GREAT Charles Dickens, one of England’s most famous TOWERS OF NOTRE DAME; THREE HUNDRED THOUSAND and beloved authors, was born February 7, 1812 MEN, SUMMONED TO RISE AGAINST THE TYRANTS OF in Portsmouth, England. -

Furies of the Guillotine: Female Revolutionaries In

FURIES OF THE GUILLOTINE: FEMALE REVOLUTIONARIES IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND IN VICTORIAN LITERARY IMAGINATION A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History by Tori Anne Horton FALL 2016 © 2016 Tori Anne Horton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii FURIES OF THE GUILLOTINE: FEMALE REVOLUTIONARIES IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND IN VICTORIAN LITERARY IMAGINATION A Thesis by Tori Anne Horton Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Mona Siegel __________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Rebecca Kluchin ____________________________ Date iii Student: Tori Anne Horton I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Department Chair ___________________ Dr. Jeffrey Wilson Date Department of History iv Abstract of FURIES OF THE GUILLOTINE: FEMALE REVOLUTIONARIES IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND IN VICTORIAN LITERARY IMAGINATION by Tori Anne Horton The idea of female revolutionaries struck a particular chord of terror both during and after the French Revolution, as represented in both legislation and popular literary imagination. The level and form of female participation in the events of the Revolution varied among social classes. Female participation during the Revolution led to an overwhelming fear of women demanding and practicing democratic rights in both a nonviolent manner (petitioning for education, demanding voting rights, serving on committees), and in a violent manner (engaging in armed protest and violent striking). The terror surrounding female democratic participation was manifested in the fear of the female citizen, or citoyenne. -

English Round Between How a Word/Phrase Should 2017 – Senior Division Coaches Practice Be Pronounced and What You See

Students: Throughout this competition, foreign Indiana Academic Super Bowl names and words may be used. If there are any discrepancies English Round between how a word/phrase should 2017 – Senior Division Coaches Practice be pronounced and what you see A Program of the Indiana Association of School Principals on the screen, the screen supersedes what is spoken. SD-CP-E-1 SD-CP-E-2 The opening sentence of A Tale of Two The epigraph to “Don Juan: Dedication” is “Difficile est proprie communia dicere.” Which of the Cities, offers examples of each of the following BEST translates that sentence? following EXCEPT _______ A. It is appropriate to tell the truth as one laughs. A. antithesis B. It is difficult to speak of the universal specifically. B. metonymy C. It is desirable to use one’s gifts for the good of C. parallelism the community. D. It is sufficient to combine well-chosen words D. polysyndeton in a well-ordered line. 1 SD-CP-E-3 SD-CP-E-4 In Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, Jarvis Lorry protests, “Feelings! I have no time for them, no change of them.” In the first stanza of “Don Juan: Dedication,” Byron However, the truth that he does have feelings is BEST says Southey “turned out a Tory.” In fact, he was a supported by the way he ________ Tory Member of Parliament. A Tory is understood to support each of the following EXCEPT _______ A. observes the intricately carved frame of the pier-glass in the room in which Lucie sits A. -

Monsters Most Dreadful: Institutions in a Tale of Two Cities

Monsters Most Dreadful: Institutions in A Tale of Two Cities by Natalie Kopp, Westerville South High School Resurrection, in a variety of forms, arises as a central motif throughout Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. Repeatedly, individuals are “recalled to life” by someone who loves them—Lucie Manette brings her father back after he has been “buried alive for eighteen years” (20); she gives testimony that helps save her husband-to-be from almost certain death by the English courts; Sydney Carton gives his life to save Lucie’s family, resurrecting them; and, in turn, Lucie’s family recalls Carton to life through their memories for years to come. Examples abound of loving individuals who, in recalling and being recalled, create a legacy for themselves and their principles. But what about the powerful institutions that ensnare the lives of all these individuals? What ensures their longevity? Writing the novel in a time of political unrest and fear of revolution in England (just a decade after the European revolutions of 1848), Dickens devotes considerable detail to creating portraits of such institutions as the French aristocracy, the new French Republic, the British and French court systems, and Tellson’s Bank. Through these portrayals, he sends a message to his country and to future societies about the fate of such institutions: A group or institution that depersonalizes and does not respect individuals will ultimately die out, while a group that honors such basic human virtues as empathy, love, and compassion will live on. Individual virtues can be quite easily overshadowed by group dynamics, but Dickens makes it clear that love and empathy are so essential to the human spirit that, so long as there are individuals who will stand up for these virtues, no group or society can sustain itself without them. -

A Tangible Resistance WORDS and PHOTOGRAPHS: Leanne Fischler

005 PROTEST A tangible resistance WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHS: Leanne Fischler WHISPER Revolutions have always played a vital part in shaping the way our society and political systems are run today. Yet behind every revolution there are secret objects, ingeniously shaped by raw necessity, to guide, unite, hide and inspire. 005 PROTEST Above Solidarnosc badge and moc resistor Image courtesy of V&A London hildren love the idea of secrets; Social movements is the art of hiding messages communication in history amongst these: chess puzzles, lovers ‘kisses’ more than a tool of communication between book, also called “Disobedient they allow them to know something are one of the in plain sight. It is the art of through the literature of the at the end of letters, and knitted jumpers. the revolutionaries, Madame Defarge’s Objects”, Flood and Grindon Cabove other people, yet why are primary engines whispering your secret in a Victorian poets. In his study Before the advances of digital knitting itself is turned from something described their choice of title as secret communications needed in today’s producing our crowded room. “Cowley’s Lemmon: Secrecy cryptography, intelligence agencies had domestic into an object full of horrific, inspired by normal, every day adult society? When people feel a lack of culture and politics, Objects have always been and Interpretation in The to use physical objects to convey their fastidious secrecy. things that are used in new and and this is no less openness in a political situation, when used as part of revolutions, for Mistress” he describes the communications and signals. -

MADAME DEFARGE Copyright © 2019, Wendy Kesselman

MADAME DEFARGE This score has been downloaded from www.dramatists.comwritten and composedand is for perusal by only. WENDY KESSELMAN No performancearranged or use by of this score is CHRISTOPHER BERG allowed without written authorization from Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Full Score MADAME DEFARGE This score has been downloaded from www.dramatists.comwritten and composedand is for perusal by only. WENDY KESSELMAN No performancearranged or use by of this score is CHRISTOPHER BERG allowed without written authorization from Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Full Score MADAME DEFARGE Copyright © 2019, Wendy Kesselman All Rights Reserved MADAME DEFARGE is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), or stored in any retrieval systemThis in any way score (electronic has or mechan beenical) withoutdownloaded written permission from of the publisher. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessionswww.dramatists.com and Canada for MADAME DEFARGE andare cont rolledis for exclusively perusal by Dramatists only. Play Service, 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of Dramatists Play Service and paying the requisite fee. -

A Tale of Two Cities Charles Dickens Charles Dickens

A Tale of Two Cities Charles Dickens Charles Dickens • Born February 7, 1812 • Died June 9, 1870 Charles Dickens • Famous writer and social critic Charles Dickens CHILDHOOD • Dickens was raised in poverty. • His father was put in debtor’s prison. • His mother and younger siblings eventually joined their father in debtor’s prison. Charles Dickens FACTORY WORK • At the age of 12, he was forced to drop out of school to work. • He was sent to Warren’s Blacking Factory, where he worked 10 hour shifts. • His job was to paste labels on pots of black shoe polish. Warren’s Blacking Factory “The blacking-warehouse …was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again.” –Charles Dickens Charles Dickens HIS MOTHER, LATER WORK • Later, Dickens’ family received an inheritance, allowing his family to leave debtor’s prison. • However, his mother did not immediately remove him from the factory. She fought to send him back. • Later, he worked for a lawyer and as a reporter. "I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back.“ –Charles Dickens Charles Dickens WRITING INFLUENCES • These experiences never left Dickens. • His novels include depictions of child poverty, debtor’s prison, cruel adults, factory life, courtrooms, and social injustice. -

A Masterpiece Teacher's Guide

A Tale of Two Cities A MASTERPIECE TEACHER’S GUIDE ILLUSTRATION BY JOHN MCLENAN, 1859 INTRODUCTION his Teacher’s Guide is a resource for educators to be used with the Masterpiece Tfilm,A Tale of Two Cities. The film, which Masterpiece originally aired in 1989 on PBS, is available for purchase from shopPBS.org. Starring James Wilby, Xavier Deluc, and Serena Gordon, and directed by Philippe Monnier, the film is a detailed adaptation of Dickens’s complex story of the lives of English and French characters caught up in the turmoil preceding and during the French Revolution. Written in 1859, A Tale of Two Cities explores issues also associated with other works of Charles Dickens: poverty, oppression, cruelty, social disruption, justice, personal redemption, and class struggle. As scenes in the story shift between the cities of Paris and London, Dickens explores these themes in both locations. The circumstances that provoked the revolution, as well as the chaotic consequences of the revolutionaries’ victory, serve as a warning directed at unaddressed and unresolved social concerns in England. Everywhere, poverty and oppression stand in sharp contrast to justice and love. Through the lives of characters drawn from many class levels in both England and France, Dickens weaves his intricate plot. A master of dramatic narrative full of vivid scenes and coincidences, Dickens is able to link the lives of diverse characters who represent the competing forces of that memorable era. To this day, Madame Defarge personifies revenge, just as the Marquis St. Evrémonde stands for corruption and cruelty. Sydney Carton represents the extremes to which one might go to salvage a wasted life.