Access to Information Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Base 'Less Than Enthusiastic' As PM Trudeau Prepares to Defend

Big Canadian challenge: the world is changing in Health disruptive + powerful + policy transformative briefi ng ways, & we better get HOH pp. 13-31 a grip on it p. 12 p.2 Hill Climbers p.39 THIRTIETH YEAR, NO. 1602 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSPAPER MONDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2019 $5.00 News Liberals News Election 2019 News Foreign policy House sitting last Trudeau opportunity for Liberal base ‘less than ‘masterful’ at Trudeau Liberals soft power, to highlight enthusiastic’ as PM falling short on achievements, hard power, says control the Trudeau prepares to ex-diplomat agenda and the Rowswell message, says a defend four-year record BY PETER MAZEREEUW leading pollster rime Minister Justin Trudeau Phas shown himself to be one to ‘volatile electorate,’ of the best-ever Canadian leaders BY ABBAS RANA at projecting “soft power” on the world stage, but his government’s ith the Liberals and Con- lack of focus on “hard power” servatives running neck W is being called into question as and neck in public opinion polls, say Liberal insiders Canada sits in the crosshairs of the 13-week sitting of the House the world’s two superpowers, says is the last opportunity for the The federal Liberals are heading into the next election with some members of the a former longtime diplomat. Continued on page 35 base feeling upset that the party hasn’t recognized their eff orts, while it has given Continued on page 34 special treatment to a few people with friends in the PMO, say Liberal insiders. Prime News Cybercrime Minister News Canada-China relations Justin Trudeau will RCMP inundated be leading his party into Appointing a the October by cybercrime election to special envoy defend his reports, with government’s a chance for four-year little success in record before ‘moral suasion’ a volatile prosecution, electorate. -

April 28, 2020 Honourable Catherine Mckenna Minister of Infrastructure

April 28, 2020 Honourable Catherine McKenna Minister of Infrastructure and Communities [email protected] Dear Minister McKenna, We write as twenty (20) business organizations representing a broad cross-section of Manitoba’s economy collectively employing tens of thousands of women and men. Those industries include engineering & consulting, heavy civil and 2 vertical construction, commercial and residential development, manufacturing & exporting, retail, agriculture, commercial trucking and skilled trades. Our appeal to the federal government is that it assist in our provincial economic recovery by accelerating the approvals of and flexibility in the allocation from federal programs. Such measures would enable funding of key Manitoba projects that would immediately procure jobs, build legacy assets and be key instruments in help kick-staring Manitoba’s economy. The above is necessary to help correct the lack of confidence in the economy by all its sectors, the alarm, anxiety and fear of what lies ahead around the corner, and indeed where that corner is. That has led to private-sector projects being deferred or outright canceled. Those decision have resulted in lost jobs, supply and equipment sales, all of which reduces the collective ROI to GDP. Addressing consumer and investor confidence is critical to our recovery. In that regard, we understand the Province of Manitoba has communicated its commitment to flow its capital programs, harnessing investment in infrastructure to help Manitoba’s economy recover. We are told Manitoba has more than $6B in project submissions for the Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program (ICIP) with many being shovel ready. We urge the federal government to make the most of the current market conditions - competitive bid prices and extraordinarily low interest rates - to meet the formidable economic challenge in front of us. -

Dealing with Crisis

Briefing on the New Parliament December 12, 2019 CONFIDENTIAL – FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY Regional Seat 8 6 ON largely Flip from NDP to Distribution static 33 36 Bloc Liberals pushed out 10 32 Minor changes in Battleground B.C. 16 Liberals lose the Maritimes Goodale 1 12 1 1 2 80 10 1 1 79 1 14 11 3 1 5 4 10 17 40 35 29 33 32 15 21 26 17 11 4 8 4 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 BC AB MB/SK ON QC AC Other 2 Seats in the House Other *As of December 5, 2019 3 Challenges & opportunities of minority government 4 Minority Parliament In a minority government, Trudeau and the Liberals face a unique set of challenges • Stable, for now • Campaign driven by consumer issues continues 5 Minority Parliament • Volatile and highly partisan • Scaled back agenda • The budget is key • Regulation instead of legislation • Advocacy more complicated • House committee wild cards • “Weaponized” Private Members’ Bills (PMBs) 6 Kitchen Table Issues and Other Priorities • Taxes • Affordability • Cost of Living • Healthcare Costs • Deficits • Climate Change • Indigenous Issues • Gender Equality 7 National Unity Prairies and the West Québéc 8 Federal Fiscal Outlook • Parliamentary Budget Officer’s most recent forecast has downgraded predicted growth for the economy • The Liberal platform costing projected adding $31.5 billion in new debt over the next four years 9 The Conservatives • Campaigned on cutting regulatory burden, review of “corporate welfare” • Mr. Scheer called a special caucus meeting on December 12 where he announced he was stepping -

Mass Cancellations Put Artists' Livelihoods at Risk; Arts Organizations in Financial Distress

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau March 17, 2020 Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland The Honourable Steven Guilbeault The Honourable William Francis Morneau Minister of Canadian Heritage Minister of Finance The Honourable Mona Fortier The Honourable Navdeep Bains Minister of Middle-Class Prosperity Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry Associate Minister of Finance The Honourable Mélanie Joly Minister of Economic Development and Official Languages Re: Mass cancellations put artists’ livelihoods at risk; arts organizations in financial distress Dear Prime Minister Trudeau; Deputy Prime Minister Freeland; and Ministers Guilbeault, Morneau, Fortier, Joly, and Bains, We write as the leadership of Opera.ca, the national association for opera companies and professionals in Canada. In light of recent developments around COVID-19 and the waves of cancellations as a result of bans on mass gatherings, Opera.ca is urgently requesting federal aid on behalf of the Canadian opera sector and its artists -- its most essential and vulnerable people -- while pledging its own emergency support for artists in desperate need. Opera artists are the heart of the opera sector, and their economic survival is in jeopardy. In response to the dire need captured by a recent survey conducted by Opera.ca, the board of directors of Opera.ca today voted for an Opera Artists Emergency Relief Fund to be funded by the association. Further details will be announced shortly. Of the 14 professional opera companies in Canada, almost all have cancelled their current production and some the remainder of the season. This is an unprecedented crisis with long-reaching implications for the entire Canadian opera sector. -

Canadian Union of Public Employees

CANADIAN UNION OF PUBLIC EMPLOYEES LOCAL 500 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Central Council October 28, 2019 TO: All Central Council Delegates RE: PRESIDENT’S REPORT BARGAINING UPDATES Local 500 members working at the St. Boniface Museum have ratified a new collective agreement. The new agreement will provide members with improvements in a number of areas such as training and development, inclement weather and hours of work. The new agreement will expire on December 31, 2022. JOINT LABOUR MANAGEMENT MEETING – CITY/LOCAL 500 On September 25, a joint labour management meeting took place between Local 500 and the City of Winnipeg. The purpose of these meetings is to provide a forum for meaningful consultation and discussion between the employer and the union regarding workplace issues and matters of mutual concern (i.e. city-wide policies, programs, and operational issues). It is not a substitute for the grievance procedure and collective bargaining process. Both parties have agreed to meet on a quarterly basis and alternate meeting locations. The next meeting has been tentatively set for December. FEDERAL ELECTION On October 21, Canadians elected a Liberal minority government. While it wasn’t the outcome we were hoping for, workers will now have a strong voice in Parliament given the NDP hold the balance of power. CUPE will continue to work with the NDP to make the sure that the new government respects its promises to Canadians. Justin Trudeau will have to translate his campaign commitments into meaningful actions to fight climate change, to create a public and universal pharmacare program, and to make life more affordable for Canadian families. -

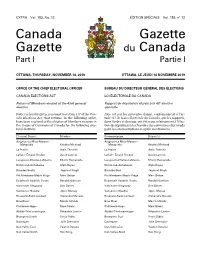

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

Core 1..16 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 42e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 22 No 22 Monday, February 22, 2016 Le lundi 22 février 2016 11:00 a.m. 11 heures PRAYER PRIÈRE GOVERNMENT ORDERS ORDRES ÉMANANT DU GOUVERNEMENT The House resumed consideration of the motion of Mr. Trudeau La Chambre reprend l'étude de la motion de M. Trudeau (Prime Minister), seconded by Mr. LeBlanc (Leader of the (premier ministre), appuyé par M. LeBlanc (leader du Government in the House of Commons), — That the House gouvernement à la Chambre des communes), — Que la Chambre support the government’s decision to broaden, improve, and appuie la décision du gouvernement d’élargir, d’améliorer et de redefine our contribution to the effort to combat ISIL by better redéfinir notre contribution à l’effort pour lutter contre l’EIIL en leveraging Canadian expertise while complementing the work of exploitant mieux l’expertise canadienne, tout en travaillant en our coalition partners to ensure maximum effect, including: complémentarité avec nos partenaires de la coalition afin d’obtenir un effet optimal, y compris : (a) refocusing our military contribution by expanding the a) en recentrant notre contribution militaire, et ce, en advise and assist mission of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in développant la mission de conseil et d’assistance des Forces Iraq, significantly increasing intelligence capabilities in Iraq and armées canadiennes (FAC) en Irak, en augmentant theatre-wide, deploying CAF medical personnel, -

A Parliamentarian's

A Parliamentarian’s Year in Review 2018 Table of Contents 3 Message from Chris Dendys, RESULTS Canada Executive Director 4 Raising Awareness in Parliament 4 World Tuberculosis Day 5 World Immunization Week 5 Global Health Caucus on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria 6 UN High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis 7 World Polio Day 8 Foodies That Give A Fork 8 The Rush to Flush: World Toilet Day on the Hill 9 World Toilet Day on the Hill Meetings with Tia Bhatia 9 Top Tweet 10 Forging Global Partnerships, Networks and Connections 10 Global Nutrition Leadership 10 G7: 2018 Charlevoix 11 G7: The Whistler Declaration on Unlocking the Power of Adolescent Girls in Sustainable Development 11 Global TB Caucus 12 Parliamentary Delegation 12 Educational Delegation to Kenya 14 Hearing From Canadians 14 Citizen Advocates 18 RESULTS Canada Conference 19 RESULTS Canada Advocacy Day on the Hill 21 Engagement with the Leaders of Tomorrow 22 United Nations High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis 23 Pre-Budget Consultations Message from Chris Dendys, RESULTS Canada Executive Director “RESULTS Canada’s mission is to create the political will to end extreme poverty and we made phenomenal progress this year. A Parliamentarian’s Year in Review with RESULTS Canada is a reminder of all the actions decision makers take to raise their voice on global poverty issues. Thank you to all the Members of Parliament and Senators that continue to advocate for a world where everyone, no matter where they were born, has access to the health, education and the opportunities they need to thrive. “ 3 Raising Awareness in Parliament World Tuberculosis Day World Tuberculosis Day We want to thank MP Ziad Aboultaif, Edmonton MPs Dean Allison, Niagara West, Brenda Shanahan, – Manning, for making a statement in the House, Châteauguay—Lacolle and Senator Mobina Jaffer draw calling on Canada and the world to commit to ending attention to the global tuberculosis epidemic in a co- tuberculosis, the world’s leading infectious killer. -

List of Mps on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency

List of MPs on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency Adam Vaughan Liberal Spadina – Fort York, ON Alaina Lockhart Liberal Fundy Royal, NB Ali Ehsassi Liberal Willowdale, ON Alistair MacGregor NDP Cowichan – Malahat – Langford, BC Anthony Housefather Liberal Mount Royal, BC Arnold Viersen Conservative Peace River – Westlock, AB Bill Casey Liberal Cumberland Colchester, NS Bob Benzen Conservative Calgary Heritage, AB Bob Zimmer Conservative Prince George – Peace River – Northern Rockies, BC Carol Hughes NDP Algoma – Manitoulin – Kapuskasing, ON Cathay Wagantall Conservative Yorkton – Melville, SK Cathy McLeod Conservative Kamloops – Thompson – Cariboo, BC Celina Ceasar-Chavannes Liberal Whitby, ON Cheryl Gallant Conservative Renfrew – Nipissing – Pembroke, ON Chris Bittle Liberal St. Catharines, ON Christine Moore NDP Abitibi – Témiscamingue, QC Dan Ruimy Liberal Pitt Meadows – Maple Ridge, BC Dan Van Kesteren Conservative Chatham-Kent – Leamington, ON Dan Vandal Liberal Saint Boniface – Saint Vital, MB Daniel Blaikie NDP Elmwood – Transcona, MB Darrell Samson Liberal Sackville – Preston – Chezzetcook, NS Darren Fisher Liberal Darthmouth – Cole Harbour, NS David Anderson Conservative Cypress Hills – Grasslands, SK David Christopherson NDP Hamilton Centre, ON David Graham Liberal Laurentides – Labelle, QC David Sweet Conservative Flamborough – Glanbrook, ON David Tilson Conservative Dufferin – Caledon, ON David Yurdiga Conservative Fort McMurray – Cold Lake, AB Deborah Schulte Liberal King – Vaughan, ON Earl Dreeshen Conservative -

Outspoken Liberal MP Wayne Long Could Face Contested Nomination

THIRTIETH YEAR, NO. 1617 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSPAPER WEDNESDAY, MARCH 27, 2019 $5.00 Senate to ditch Phoenix in January p. 5 The Kenney campaign con and the new meaning of narrative: PCO clerk Budget puts off transition: what pharmacare reform, but Lisa Van Dusen feds say it takes the fi rst p. 9 to expect p. 6 ‘concrete steps’ p. 7 News Politics News Parliamentary travel Tories block some House Outspoken Liberal MP committee travel, want to stay in Ottawa as election looms Wayne Long could face Half of all committee trips BY NEIL MOSS that have had their travel he Conservatives are blocking budgets approved by THouse committee travel, say contested nomination some Liberal committee chairs, the Liaison Committee’s but Tory whip Mark Strahl sug- gested it’s only some trips. Budgets Subcommittee A number of committees have Liberal MP had travel budgets approved by Wayne Long since November have the Liaison Committee’s Subcom- has earned a not been granted travel mittee on Committee Budgets, reputation as an but have not made it to the next outspoken MP, authority by the House of step to get travel authority from something two New Brunswick Commons. Continued on page 4 political scientists say should help News him on the Politics campaign trail in a traditionally Conservative Ethics Committee defeats riding. The Hill Times photograph by opposition parties’ motion to Andrew Meade probe SNC-Lavalin aff air Liberal MP Nathaniel BY ABBAS RANA Erskine-Smith described week after the House Justice the opposition parties’ ACommittee shut down its He missed a BY SAMANTHA WRIGHT ALLEN The MP for Saint John- probe of the SNC-Lavalin affair, Rothesay, N.B., is one of about 20 motion as ‘premature,’ the House Ethics Committee also deadline to meet utspoken Liberal MP Wayne Liberal MPs who have yet to be as the Justice Committee defeated an opposition motion Long could face a fi ght for nominated. -

George Committees Party Appointments P.20 Young P.28 Primer Pp

EXCLUSIVE POLITICAL COVERAGE: NEWS, FEATURES, AND ANALYSIS INSIDE HARPER’S TOOTOO HIRES HOUSE LATE-TERM GEORGE COMMITTEES PARTY APPOINTMENTS P.20 YOUNG P.28 PRIMER PP. 30-31 CENTRAL P.35 TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR, NO. 1322 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2016 $5.00 NEWS SENATE REFORM NEWS FINANCE Monsef, LeBlanc LeBlanc backs away from Morneau to reveal this expected to shed week Trudeau’s whipped vote on assisted light on deficit, vision for non- CIBC economist partisan Senate dying bill, but Grit MPs predicts $30-billion BY AbbaS RANA are ‘comfortable,’ call it a BY DEREK ABMA Senators are eagerly waiting to hear this week specific details The federal government is of the Trudeau government’s plan expected to shed more light on for a non-partisan Red Cham- Charter of Rights issue the size of its deficit on Monday, ber from Government House and one prominent economist Leader Dominic LeBlanc and Members of the has predicted it will be at least Democratic Institutions Minister Joint Committee $30-billion—about three times Maryam Monsef. on Physician- what the Liberals promised dur- The appearance of the two Assisted ing the election campaign—due to ministers at the Senate stand- Suicide, lower-than-expected tax revenue ing committee will be the first pictured at from a slow economy and the time the government has pre- a committee need for more fiscal stimulus. sented detailed plans to reform meeting on the “The $10-billion [deficit] was the Senate. Also, this is the first Hill. The Hill the figure that was out there official communication between Times photograph based on the projection that the the House of Commons and the by Jake Wright economy was growing faster Senate on Mr. -

Charitable Registration Number: 10684 5100 RR0001 Hon. Patty Hajdu Minister of Health Government of Canada February 27, 2021

Cystic Fibrosis Canada Ontario Suite 800 – 2323 Yonge Street Toronto, ON M4P 2C9 416.485.9149 ext. 297 [email protected] www.cysticfibrosis.ca Hon. Patty Hajdu Minister of Health Government of Canada February 27, 2021 Dear Minister Hajdu, We are members of an all-party caucus on emergency access to Trikafta, a game-changing therapy that can treat 90% of the cystic fibrosis population. We are writing to thank you for your commitment to fast- tracking access to Trikafta and to let you know that we are here to collaborate with you in this work. We know that an application for review of Trikafta was received by Health Canada on December 4th, 2020 and was formally accepted for review on December 23rd. We are also aware that the Canadian Agency for Drugs Technologies in Health (CADTH) body that evaluates the cost effectiveness of drugs is now reviewing Trikafta for age 12 plus for patients who have at least one F508del mutation. This indicates that Trikafta was granted an ‘aligned review,’ the fastest review route. The aligned review will streamline the review processes by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) to set the maximum amount for which the drug can be sold, and by Health Technology Assessment bodies (CADTH and INESSS) to undertake cost-effective analyses, which can delay the overall timeline to access to another 6 months or more. An aligned review will reduce the timelines of all of these bodies to between 8-12 months or sooner. But that is just one half of the Canadian drug approval system.