Ray Bradbury and the Struggle for Prestige in Postwar Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

FANTASY NEWS TEN CENTS the Science Fiction Weekly Newspaper Volume 4, Number 21 Sunday, May 12

NEWS PRICE: WHILE THREE IT’S ISSUES HOT! FANTASY NEWS TEN CENTS the science fiction weekly newspaper Volume 4, Number 21 Sunday, May 12. 1940 Whole Number 99 FAMOUS FANTASTIC FACTS SOCIAL TO BE GIVEN BY QUEENS SFL THE TIME STREAM The next-to-last QSFL meeting which provided that the QSFL in Fantastic Novels, long awaited The Writer’s Yearbook for 1940 of the 39-40 season saw an attend vestigate the possibilities of such an companion magazine to Famous contains several items of consider ance of close to thirty authors and idea. The motion was passed by a Fantastic Mysteries, arrived on the able interest to the science fiction fans. Among those present were majority with Oshinsky. Hoguet. newsstands early this week. This fan. There is a good size picture of Malcolm Jameson, well know stf- and Unger on investigating com new magazine presents the answer Fred Pohl, editor of Super Science author; Julius Schwartz and Sam mittee. It was pointed out that if to hundreds of stfans who wanted and Astonishing, included in a long Moskowitz, literary agents special twenty fans could be induced to pay to read the famous classics of yester pictorial review of all Popular Pub izing in science fiction; James V. ten dollars apiece it would provide year and who did not like to wait lications; there is also, the informa Taurasi. William S. Sykora. Mario two hundred dollars which might months for them to appear in serial tion that Harl Vincent has had ma Racic, Jr., Robert G. Thompson, be adequate to rent a “science fiction terial in Detective Fiction Weekly form. -

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

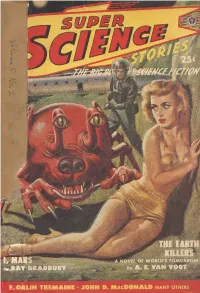

Super Science Stories V05n02 (1949 04) (Slpn)

’yf'Ti'-frj r " J * 7^ i'irT- 'ii M <»44 '' r<*r^£S JQHN D. Macdonald many others ) _ . WE WILL SEND ANY ITEM YOU CHOOSE rOR APPROVAL UNDER OUR MONEY BACK GUARANTEE Ne'^ MO*' Simply Indicate your selection on the coupon be- low and forward it with $ 1 and a brief note giv- ing your age, occupotion, and a few other facts about yourself. We will open an account for ycu and send your selection to you subject to your examination, tf completely satisfied, pay the Ex- pressman the required Down Payment and the balance In easy monthly payments. Otherwise, re- turn your selection and your $1 will be refunded. A30VC112 07,50 A408/C331 $125 3 Diamond Engagement 7 Dtomond Engagement^ Ring, matching ‘5 Diamond Ring, matching 8, Dior/tond Wedding Band. 14K yellow Wedding 5wd. 14K y<dlow or IBK white Gold. Send or I8K white Cold, fiend $1, poy 7.75 after ex- $1, pay .11.50 after ex- amination, 8.75 a month. aminatioii, 12.50 a month. ^ D404 $75 Man's Twin Ring with 2 Diamonds, pear-shaped sim- ulated Ruby. 14K yellow Gold. Send $1, pay 6.50 after examination, 7.50 a month* $i with coupon — pay balance op ""Tend [ DOWN PAYMENT AFTER EXAMINATION. I, ''All Prices thciude ''S T'" ^ ^ f<^erat fox ", 1. W. Sweet, 25 West 1 4th St. ( Dept. PI 7 New York 1 1, N, Y. Enclosed find $1 deposit. Solid me No. , , i., Price $ - After examination, I ogree to pay $ - - and required balance monthly thereafter until full price . -

A Ficção Científica De Acordo Com Os Futurians Science Fiction According

A ficção científica de acordo com os Futurians Science Fiction According to the Futurians Andreya Susane Seiffert1 DOI: 10.19177/memorare.v8e12021204-216 Resumo: The Futurian Society of New York, ou simplesmente The Futurians, foi um grupo de fãs e posteriormente escritores e editores de ficção científica, que existiu de 1938 a 1945. O período é geralmente lembrado pela atuação do editor John Cambpell Jr. à frente da Astounding Science Fiction. A revista era, de fato, a principal pulp à época e moldou muito do que se entende por ficção científica até hoje. Os Futurians eram, de certa forma, uma oposição a Campbell e seu projeto. Três membros do grupo viraram editores também e foram responsáveis por seis revistas pulps diferentes, em que foram publicadas dezenas de histórias com autoria dos Futurians. Esse artigo analisa parte desse material e procura fazer um pequeno panorama de como os Futurians pensaram e praticaram a ficção científica no início da década de 1940. Palavras-chave: Ficção Científica. Futurians. Abstract: The Futurian Society of New York, or simply The Futurians, was a group of fans and later writers and editors of science fiction, which existed from 1938 to 1945. The period is generally remembered for the role of editor John Cambpell Jr. at the head of Astounding Science Fiction. The magazine was, in fact, the main pulp at the time and shaped much of what is understood by science fiction until today. The Futurians were, in a way, an opposition to Campbell and his project. Three members of the group became editors as well and were responsible for six different pulp magazines, in which dozens of stories were published by the Futurians. -

Adventures 'Frstar Pirate Battles the Murder Monsters of Mercury P L a N E T

No 4 $4.50 , Toles of Scientif iction Adventures 'frStar Pirate battles the murder monsters of Mercury P l a n e t A \ s v Monorail to Eternity by Carl Jacobi Number Four Agril 1988 CONTENTS The Control Room 2 Monorail to Eternity................... Carl Jacobi 3 Condemned by the Rulers of an alien world to endless, aimless flight beneath the planet's surface! Planet in Peril Lin Carter 27 Star Pirate battles the murder monsters of Mer c u r y ! Zeppelins of the V o i d .............. Jason Rainbow 43 Can even galactic vigilante Solar Smith de feat the pernicious pirates of space? What Hath M e ? ........................ Henry Kuttner 55 He felt the lifeblood being sucked out of him— deeper stabbled the gelid cold . then the voice came, "Crush the heart!" Ethergrams........................................... 77 We've got quite a crew assembled some years back for the ill-starred here for our latest madcap mission pulp Spicy Zeppelin Stories before into make-believe mayhem! Me, I'm that mag folded. Alas! Finally, Captain Astro, and my trusty crew our terrific "Tales from the Time- of raygun-slingers are just itching Warp" features Henry Kuttner's "What to see some extraterrestrial action. Hath Me?," a neglected classic from Let me introduce you. First off, Planet Stories. Thanks to space- there's Carl Jacobi, veteral of pulps hounds Robert Weinberg who suggested from Startling Stories to Comet Sci this one and Dan Gobbett who dredged ence Fiction, bringing you this time up a copy for us! With a team like another atom-smashing epic from -

Eng 4936 Syllabus

ENG 4936 (Honors Seminar): Reading Science Fiction: The Pulps Professor Terry Harpold Spring 2019, Section 7449 Time: MWF, per. 5 (11:45 AM–12:35 PM) Location: Little Hall (LIT) 0117 office hours: M, 4–6 PM & by appt. (TUR 4105) email: [email protected] home page for Terry Harpold: http://users.clas.ufl.edu/tharpold/ e-Learning (Canvas) site for ENG 4936 (registered students only): http://elearning.ufl.edu Course description The “pulps” were illustrated fiction magazines published between the late 1890s and the late 1950s. Named for the inexpensive wood pulp paper on which they were printed, they varied widely as to genre, including aviation fiction, fantasy, horror and weird fiction, detective and crime fiction, railroad fiction, romance, science fiction, sports stories, war fiction, and western fiction. In the pulps’ heyday a bookshop or newsstand might offer dozens of different magazines on these subjects, often from the same publishers and featuring work by the same writers, with lurid, striking cover and interior art by the same artists. The magazines are, moreover, chock-full of period advertising targeted at an emerging readership, mostly – but not exclusively – male and subject to predictable The first issue of Amazing Stories, April 1926. Editor Hugo Gernsback worries and aspirations during the Depression and Pre- promises “a new sort of magazine,” WWII eras. (“Be a Radio Expert! Many Make $30 $50 $75 featuring the new genre of a Week!” “Get into Aviation by Training at Home!” “scientifiction.” “Listerine Ends Husband’s Dandruff in 3 Weeks!” “I’ll Prove that YOU, too, can be a NEW MAN! – Charles Atlas.”) The business end of the pulps was notoriously inconstant and sometimes shady; magazines came into and went out of publication with little fanfare; they often changed genres or titles without advance notice. -

The Inventory of the Evan Hunter Collection #377

The Inventory of the Evan Hunter Collection #377 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center "'•\; RESTRICTION: Letters of ... ~. -..:::.~~- / / 12/20/67 & 1/11/68 HlJN'.J.lER, EVAN ( 112 items (mags. ) ) (167 items (short stories)) I. IV:ag-a.zines with E .H. stories ( arranged according to magazine and with dates of issues.) 11 Box 1 1. Ten Sports Stories, Hunt Collins ( pseua.~ "let the Gods Decide , '7 /52 2. Supe:c Sports, Hunt Collins (pseud.) "Fury on First" 12/51 3. Gunsmoke, "Snowblind''; 8/53 "The Killing at Triple Tree" 6/53 oi'l31 nal nllrnt:,, l1.. Famous viestej:n, S .A. Lambino ~tltt.7 11 The Little Nan' 10/52; 11 Smell the Blood of an J:!!nglishman" 5. War Stories, Hunt Collins (pseud.) 11 P-A-~~-R-O-L 11 11/52 1 ' Tempest in a Tin Can" 9/52 6. Universe, "Terwilliger and the War Ivi3,chine" 9 / 9+ 7. Fantastic J\dvantures Ted •raine (1,seud,) "Woman's World" 3/53 8. '.l'hrilling Wonder Stories, "Robert 11 ~-/53 "End as a Robot", Richard M,trsten ( pseud. ) Surrrrner /54 9, Vortex, S ,A. Lambino "Dea.le rs Choice 11 '53 .10. Cosmos, unic1entified story 9/53 "Outside in the Sand 11 11/53 11 11. If, "Welcome 1'/artians , S. A. J..Dmb ino w-1 5/ 52; unidentified story 11/ 52 "The Guinea Pigs", :3 .A. Lomb ino V,) '7 / 53; tmic1entified story ll/53 "rv,:alice in Wonderland", E.H. 1/54 -12. Imagination, "First Captive" 12/53; "The Plagiarist from Rigel IV, 3/5l1.; "The Miracle of Dan O I Shaugnessy" 12/5l~. -

Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Guides to Manuscript Collections Search Our Collections 2006 0749: Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006 Marshall University Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sc_finding_aids Part of the Fiction Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006, Accession No. 2006/04.0749, Special Collections Department, Marshall University, Huntington, WV. This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Search Our Collections at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides to Manuscript Collections by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 0 REGISTER OF THE NELSON SLADE BOND COLLECTION Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia 2007 1 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, WV 25755-2060 Finding Aid for the Nelson Slade Bond Collection, ca.1920-2006 Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Processor: Gabe McKee Date Completed: February 2008 Location: Special Collections Department, Morrow Library, Room 217 and Nelson Bond Room Corporate Name: N/A Date: ca.1920-2006, bulk of content: 1935-1965 Extent: 54 linear ft. System of Arrangement: File arrangement is the original order imposed by Nelson Bond with small variations noted in the finding aid. The collection was a gift from Nelson S. Bond and his family in April of 2006 with other materials forwarded in May, September, and November of 2007. -

La2-Preib/Honors 2Nd Quarter:December

ND LA2-PREIB/HONORS 2 QUARTER: DECEMBER • READING & HOMEWORK SCHEDULE [SUBJECT TO CHANGE] • NO LATE WORK WILL BE ACCEPTED. • PLEASE SEE MR. CHUNG REGARDING ANY ABSENCES. TIME FRAME: 2 WEEKS LITERATURE, READING/LIT. ANALYSIS: WRITING: SOCRATIC SEMINAR GROUPS q RAY BRADBURY, BACKGROUND INFO q ANNOTATIONS ON BACKGROUND INFO q FAHRENHEIT 451, RAY BRADBURY q F451 READER RESPONSE NOTES 1. DAY 1: ALL Students q “THE CENSORS” BY LUISA VALENZUELA [STUDY QUESTIONS, ONE-PAGERS, LIT CIRCLES] q “RAPPING NASTY” FROM SCHOLASTIC UPDATE q “THE CENSORS” WRITING ASSIGNMENT 2. DAY 2 q CENSORSHIP q “APATHY: WRITING A PATHETIC PAPER” q F451 READING NOTES (STUDY QUESTIONS, q CLASS NOTES [CORNELL NOTES] AY LIT CIRCLES) q PRE-READING QUESTIONS 3. D 3 q POST-READING QUESTIONS 4. DAY 4 LANGUAGE: LISTENING/SPEAKING: q OCABULARY FROM F451 q OCRATIC EMINARS V S S 5. DAY 5 q LITERARY DEVICES q WORLD CAFE q CONVERSATIONAL ROUNDTABLE / LIT CIRCLES 6. DAY 6 ASSESSMENT: q F451 QUIZZES 7. DAY 7 q OBJECTIVE TESTS q PART 1: “THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER” (DAYS 1-4) 8. DAY 8 q PART 2: “THE SIEVE AND THE SAND” (DAYS 5-7) q PART 3: “BURNING BRIGHT” (DAYS 8-10) AY q SUBJECTIVE FINAL: IN-CLASS ESSAY 9. D 9 q WRITING ASSIGNMENTS, SOCRATIC SEMINARS, LIT CIRCLES 10. DAY 10 MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY December 7 8 9 10 11 DUE: F451 BACKGROUND DUE: DAY 1, 2, RR NOTES DUE: DAY 3, 4, RR NOTES TURN IN: DAYS 1-4 NOTES DUE: DAY 6, 7, RR NOTES DUE: DAY 5, RR NOTES AOW DYSTOPIA DYSTOPIA 2 F451 ISSUES DYSTOPIA IN F451 SOCRATIC SEMINAR DAY 1 SOC SEM DAY 3, 4 EXAM 1 SOC SEM: DAY 6, 7 PRE-READING QUESTIONS SOC SEM DAY 2 SOC SEM: DAY 5 HW: Day 1, 2, RRN HW: Day 3, 4, RRN HW: Day 5, RRN HW: Day 6, 7, RRN HW: Day 8-10, RRN 14 15 16 17 18 TURN IN: DAYS 5-7 NOTES DUE: DAYS 9, 10, RRN TURN IN: DAYS 8-10 NOTES DUE: ACADEMIC HABITS REFLECTIVE ESSAY (G.C.) EXAM 2 WORLD CAFE: EXAM 3 ARCHETYPES DAY 9, 10 SUBJECTIVE FINAL ARCHETYPES: Hero’s F451 DAY 8 Journey HW: Day 9, 10, RRN HW: Acad. -

Ray Bradbury • Born 1920, Waukegan, Illinois • Moved to L.A

Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury • Born 1920, Waukegan, Illinois • Moved to L.A. • Graduated high school (1938) but didn’t go to college • Sold newspapers on the corner • “Libraries raised me. I don’t believe in colleges and universities. I believe in libraries because most students don’t have any money. When I graduated from high school, it was during the Depression and we had no money. I couldn’t go to college, so I went to the library three days a week for 10 years.” The Author • 1940s: Began writing stories for pulp magazines • Super Science Stories • Galaxy Science Fiction • Weird Tales • Amazing Stories • Fahrenheit 451 began as a short story: “The FireMan” • A series of five separate stories over three years The Author • Published in 1953 • Post-WWII • Cold War • McCarthyism • Suburbia • 1950s Uniformity • The Promise of Collectivity • Success in Sameness • Fear of the Unfamiliar or Different The Time • Written with a bag of dimes and a rented typewriter in the basement of a UCLA library • Written in 9 days • During McCarthyism, no one wanted to publish a novel about past, present, and future censorship • Young Chicago editor saw the manuscript and bought it for $450 to publish in issues no. 2, 3, and 4 of his yet-to- be-born magazine • Playboy The Book • Origin • “Well, Hitler of course. When I was fifteen, he burnt the books in the streets of Berlin . Then along the way I learned about the libraries in Alexandria burning five thousand years ago. That grieved my soul. Since I'm self- educated, that means my educators—the libraries—are in danger. -

Futuria 2 Wollheim-E 1944-06

-—- J K Th-1 Official Organ.?f the Futu- . _ r1an Socle tv of Few York - - /tj-s 1 Num 2 Elsie Balter Wollhelm -Ed. w "kxkkxkkkkkx-xkk xkkxkkwk-kk-xwk^kk**#**kk-if*Wkkk*kk#k*«**-ft-»<■*■**"■*■* #****'M'**'it F'jlUr.IA Is an occasional publication, which should appear no less fre quently than once every three years, for the purpose op keeping various persons connected with' the science-fiction and fantasy fan movememts a mused and. lnfr*rnre?d, along with the Executive Committee of the Society, who dedlcat'e the second Issues of the W'g official organ, to fond mem ories of the ISA. .. -/("■a- xkk k'xk x x-kxxxkk-xxkkk-xxx kwk kk it- y't-i'r x-xkkkkkk-xkxxkk xkkkxkk-k k-xkkkkwxk k-kkkk '* k-xkkkii- xkkkkkwkkkk kkkkkkkkkkkk-k kkkkkkk kk kk ii-ifr-14-"X-«<"»*■ ■»«■-ifr kkxkxk-x it- k x kkkkkkHt-k ><*** Executive Committee -- Futurlen Society of Nev/ York John B. Michel - - Director . Robert W. Lowndes, Secretarv Elsie Balter Wollhelm, Editor Donald A. Wollhoim, Treasurer Chet Cohen, Member-At-Large ■x-xxk-lt-xkk-x-x-xk-x xxk-xwk-kk-xk-xx x-x -Xk k'k kxkk-xkkkk’x-xkxk k -xkkkxkkkkkkkk-xkkkkkkkkk " ”x xkx-X x-x-x-x kxx w-frjf xx-kkx kk-x i4w xx-xk* xk x x x-x kk x-x-x -x-k kk kkxkkkk -xkkkkkkkkk-xkkkkkkkk Futurlen Society o.f. New York -- Membership List act!ve members Honor Roll..:, Members Lp Service. John B. Michel Fre.deri.k Pohl Donald A, Wellheim Richard Wilson Robert W.