Season 2012-2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sarah Mills Bacha 614.563.1066 Andrew Lloyd Webber's

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 22, 2018 Contact: Sarah Mills Bacha 614.563.1066 Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Aspects of Love at CATCO May 30-June 17 Chamber musical by one of musical theatre’s legends explores the many forms of love Love takes many forms – love between couples; romantic infatuation; the devotion of married people; and the ties of children to their parents. This chamber musical, written by one of contemporary musical theatre’s icons, Andrew Lloyd Webber, who gave us beloved classics, such as Phantom of the Opera and Evita, examines all of them. “Love Changes Everything” is the theme song of this musical first produced in 1989 in London and based upon a 1955 novella written by David Garnett, and “nothing in the world will ever be the same.” Aspects of Love, with book and music by Webber and lyrics by Don Black and Charles Hart, is presented through special arrangement with R&H Theatricals: www.rnh.com “Aspects of Love is one of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s lesser known works because it was produced after his blockbuster works of the 1970s and 1980s, but it is no less memorable with beautiful romantic lyrics and music, hallmarks of Webber musicals,” said Steven C. Anderson, CATCO producing director, who will direct CATCO’s chamber production. “If you loved the music of Phantom of the Opera, Cats and Evita and other works by Webber, you won’t want to miss CATCO’s presentation of Aspects of Love,” Anderson, said. CATCO will perform Aspects of Love, May 30-June 17, 2018, in the Studio One Theatre at the Vern Riffe Center, 77 S. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 68, 1948-1949

W fl'r. r^S^ BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON ^r /^:> ,Q 'iiil .A'^ ^VTSOv H SIXTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1948-1949 Carnegie Hall, New York Boston Symphony Orchestra [Sixty-eighth Season, 1948-1949] SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin, Joseph de Pasquale Raymond Allard Concert-master Jean Cauhape Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Georges Fourel Ralph Masters Gaston Elcus Eugen Lehner Roll and Tapley Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Norbert Lauga Emil Kornsand Boaz Piller George Zazofsky George Humphrey Horns Paul Cherkassky Louis Arti^res Harry Dubbs Charles Van Wynbergen Willem Valkenier James Stagliano Vladimir ResnikofiE Hans Werner Principals Joseph Leibovici Jerome Lipson Harry Shapiro Siegfried Gerhardt Einar Hansen Harold Meek Daniel Eisler Violoncellos Paul Keaney Norman Carol Walter Macdonald Carlos P infield Samuel Mayes Osbourne McConathy Alfred Zighera Paul Fedorovsky Harry Dickson Jacobus Langendoen Trumpets Mischa Nieland Minot Beale Georges Mager Hippolyte Droeghmans Roger Voisin Karl Zeise Clarence Knudson Prijicipals Pierre Mayer Josef Zimbler Marcel La fosse Manuel Zung Bernard Parronchi Harry Herforth Samuel Diamond Enrico Fabrizio Ren^ Voisin Leon MarjoUet Victor Manusevitch Trombones James Nagy Flutes Jacob Raichman Leon Gorodetzky Georges Laurent Lucien Hansotte Raphael Del Sordo James Pappoutsakis John Coffey Melvin Bryant Phillip Kaplan Josef Orosz John Murray Lloyd Stonestreet Piccolo Tuba Henri Erkelens George Madsen -

ORCHESTRATINGA PENTHOUSEINNEW YORKFORTHE VIRTUOSOVIOLIMST Renovationarchitecture and Design by Charlesrose, Ata Textby Stevenm

BilB ORCHESTRATINGA PENTHOUSEINNEW YORKFORTHE VIRTUOSOVIOLIMST RenovationArchitecture and Design by CharlesRose, AtA Textby StevenM. L.Aronson Photographyby ScottFrances To create his Manhattan residence,Joshua Bell (above) workedwith architect Charles Rose. RrcHr: The 4pO0-square-foot penthouse's living area. Robsiohn-Gibbings low table and Harvey Probber bentwood bench, Eric Appel. Drapery fabric, Larsen. Sofas, Cassina. Odegard rug. 110| www.ArchitecturalDigest.com Asovn: At Bell's request, the archi- tar quality: that thing r,r'hich,as the Ed- to mention the Avery Fisher Prize. On the tect put a fireplace between the liv- wardianartistWalter Sickert - ing and dining areas, one with a oncesho\\ more corporeal side,Bell was one of Glnntour's mantel that cantilevers out on one ily definedit, "can shine, on peacock "It Men of the Millennium" and one of Peopte end to double as a bar. Rietveld days,like a plume of luck abole \-our magazine's"50 Most Beautiful." chair and dining chairs, Cassina. genius."JoshuaBell hasit. Resoundineh. Home is the top two floors, Pollack shade fabric in dining area. plus roof, of a for- Ffe'sa world-classclassical r-iolinist equalh-..rt rner manufacturing plant in Manhattan's Flat- home with popular music (Jos/:rt,rBell tr Hcttte iron District, namedforits signaturebuilding- with Ft'iends,hrsfirst duetsCD. u..rsrccenrh- "To me, the Flatiron Buildinfis NewYork," Eell released,and the friendstellinelr- inclu;- Strne. enthuses.He hired architectCharles Rose to gut Josh Groban, Kristin Chenowethanti -\i.r:. rn and then combine the floors and to transfo".m Hamlisch).And he'sstarred in sir i...-.:s:,,n the saggingold roof into a positivelypagan our- specials,performed all the soloson rh: Llsc:r- door spa(there's a hot tub and a showeropen to -i+i:;: '.i., winning soundtrackforThe Redt ,:.,i ,n the sky,a trellisedpergola, a fireplaceand a cop- a Grammy, a Gramophoneand a -\It:: -.r-.-.r,-r[ per-cladchimney). -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 Fadi Kheir Fadi LETTERS from the LEADERSHIP

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 Fadi Kheir Fadi LETTERS FROM THE LEADERSHIP The New York Philharmonic’s 2019–20 season certainly saw it all. We recall the remarkable performances ranging from Berlioz to Beethoven, with special pride in the launch of Project 19 — the single largest commissioning program ever created for women composers — honoring the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Together with Lincoln Center we unveiled specific plans for the renovation and re-opening of David Geffen Hall, which will have both great acoustics and also public spaces that can welcome the community. In March came the shock of a worldwide pandemic hurtling down the tracks at us, and on the 10th we played what was to be our final concert of the season. Like all New Yorkers, we tried to come to grips with the life-changing ramifications The Philharmonic responded quickly and in one week created NY Phil Plays On, a portal to hundreds of hours of past performances, to offer joy, pleasure, solace, and comfort in the only way we could. In August we launched NY Phil Bandwagon, bringing live music back to New York. Bandwagon presented 81 concerts from Chris Lee midtown to the far reaches of every one of the five boroughs. In the wake of the Erin Baiano horrific deaths of Black men and women, and the realization that we must all participate to change society, we began the hard work of self-evaluation to create a Philharmonic that is truly equitable, diverse, and inclusive. The severe financial challenge caused by cancelling fully a third of our 2019–20 concerts resulting in the loss of $10 million is obvious. -

The-Music-Of-Andrew-Lloyd-Webber Programme.Pdf

Photograph: Yash Rao We’re thrilled to welcome you safely back to Curve for production, in particular Team Curve and Associate this very special Made at Curve concert production of Director Lee Proud, who has been instrumental in The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber. bringing this show to life. Over the course of his astonishing career, Andrew It’s a joy to welcome Curve Youth and Community has brought to life countless incredible characters Company (CYCC) members back to our stage. Young and stories with his thrilling music, bringing the joy of people are the beating heart of Curve and after such MUSIC BY theatre to millions of people across the world. In the a long time away from the building, it’s wonderful to ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER last 15 months, Andrew has been at the forefront of have them back and part of this production. Guiding conversations surrounding the importance of theatre, our young ensemble with movement direction is our fighting for the survival of our industry and we are Curve Associate Mel Knott and we’re also thrilled CYCC LYRICS BY indebted to him for his tireless advocacy and also for alumna Alyshia Dhakk joins us to perform Pie Jesu, in TIM RICE, DON BLACK, CHARLES HART, CHRISTOPHER HAMPTON, this gift of a show, celebrating musical theatre, artists memory of all those we have lost to the pandemic. GLENN SLATER, DAVID ZIPPEL, RICHARD STILGOE AND JIM STEINMAN and our brilliant, resilient city. Known for its longstanding Through reopening our theatre we are not only able to appreciation of musicals, Leicester plays a key role make live work once more and employ 100s of freelance in this production through Andrew’s pre-recorded DIRECTED BY theatre workers, but we are also able to play an active scenes, filmed on-location in and around Curve by our role in helping our city begin to recover from the impact NIKOLAI FOSTER colleagues at Crosscut Media. -

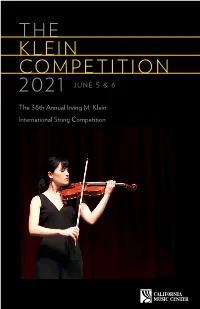

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 68, 1948

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON SIXTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1948- 1949 Academy of Music, Brooklyn Under the auspices of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences and the Philharmonic Sooety of Brooklyn Boston Symphony Orchestra [Sixty-eighth Season, 1948-1949] SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin, Joseph de Pasquale Raymond Allard Concert-master Jean Cauhape Ernst Panenka Alfred Rrips Georges Fourel Ralph Masters Gaston Elcus Eugen Lehner Rolland Tapley Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Norbert Lauga Emil Kornsand Boaz Piller George Zazofsky George Humphrey " Horns Paul Cherkassky Louis Arti^res Harry Dubbs Charles Van Wynbergen Willem Valkenier James Stagliano Vladimir Resnikoff Hans Werner Principals Joseph Leibovici Jerome Lipson Harry Shapiro Siegfried Gerhardt Einar Hansen Harold Meek Daniel Eisler Violoncellos Paul Keaney Norman Carol Walter Macdonald Carlos Pinfield Samuel Mayes Osbourne McConathy Alfred Zighera Paul Fedorovsky Harry Dickson Jacobus Langendoen Trumpets Mischa Nieland Minot Beale Georges Mager Hippolyte Droeghmans Roger Voisin Karl Zeise Clarence Knudson Principals Pierre Mayer Josef Zimbler Marcel La fosse Manuel Zung Bernard Parronchi Harry Herforth Samuel Diamond Enrico Fabrizio Rene Voisin Leon Marjollet Victor Manusevitch Trombones James Nagy Flutes Jacob Raichman Leon Gorodelzky Georges Laurent Lucien Hansotte Raphael Del Sordo James Pappoutsakii John Coffey Melvin Bryant Phillip Kaplan Josef Orosz John -

By MARTIN BOOKSPAN

December 31, 2007, 8:00pm on PBS New York Philharmonic New Year’s Eve Gala with Joshua Bell In September Live From Lincoln Center observed one of its longtime traditions: the Gala opening concert of the new season of the New York Philharmonic. On December 31 we'll re-invent another longtime Live From Lincoln Center tradition: the Gala New Year's Eve concert by the New York Philharmonic. Music Director Lorin Maazel will be on the podium for a program of music appropriate for the festive occasion, and the guest artist will be the acclaimed violinist, Joshua Bell. I first encountered Joshua Bell at the Spoleto Festival, U.S.A. in Charleston, South Carolina. He was then barely into his teens but he was already a formidable violinist, playing chamber music with some of the world's most honored musicians. Not long afterward he burst upon the international scene at what was described as "a sensational debut" with the Philadelphia Orchestra and its Music Director of the time, Riccardo Muti. Joshua Bell was brought up in Bloomington, Indiana, where his father was a Professor at Indiana University. I.U., as it is known in academia, is an extraordinary university, with a School of Music that is world-renowned. Among its outstanding faculty was the eminent violinist Josef Gingold, who became Josh's inspired (and inspiring) mentor and devoted friend. Indeed it was the presence of Gingold in Indiana that led to the establishment of the Indianapolis International Violin Competition. One way for a young musician to attract attention is to win one of the major international competitions. -

N E W S R E L E A

N E W S R E L E A S E CONTACT: Katherine Blodgett Vice President of Public Relations and Communications Phone: 215.893.1939 E-mail: [email protected] Jesson Geipel Public Relations Manager FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Phone: 215.893.3136 DATE: October 18, 2012 E-mail: [email protected] YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN’S INAUGURAL SEASON AS MUSIC DIRECTOR OF THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA BEGINS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2012, WITH A GALA CONCERT FEATURING THE INCOMPARABLE RENÉE FLEMING Opening Weeks of Nézet-Séguin’s Tenure to Feature Verdi’s Requiem, His Carnegie Hall Debut, and Concerts with Violinist Joshua Bell (Philadelphia, October 18, 2012)—Yannick Nézet-Séguin officially begins his tenure as The Philadelphia Orchestra’s eighth music director with a gala Opening Concert on October 18, 2012, two weeks of subscription concerts at the Orchestra’s home in Verizon Hall at the Kimmel Center, and with his Carnegie Hall debut on October 23 in New York City. Nézet-Séguin was named music director designate of the legendary ensemble in 2010. The gala concert, featuring soprano Renée Fleming, includes Ravel’s Shéhérazade, Brahms’s Symphony No. 4, and “Mein Elemer!” from Arabella by Richard Strauss. For the Orchestra’s first subscription series at the Kimmel Center and for his Carnegie Hall debut, Nézet-Séguin has chosen Verdi’s Requiem, featuring soprano Marina Poplavskaya, mezzo-soprano Christine Rice, tenor Rolando Villazón, bass Mikhail Petrenko, and the Westminster Symphonic Choir. Philadelphia Orchestra Association President and CEO Allison Vulgamore said, “This is the launch of a new chapter for The Philadelphia Orchestra. We have been anticipating this moment for what seems a very long time, and the entire organization couldn’t be more thrilled that it is finally upon us. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 69, 1949

MfG ^:^ (^^^^^ ' ^ ?9 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY 4 HENRY LEE HIGGIMSON 4y 7 %. m Ai j-^ r/z/iiiin/iui/if H s^ Vvv! SIXTY-NINTH SEASON 1949-1950 Sanders Theatre, Cambridge \^arvard University^ Boston Symphony Orchestra [Sixty-ninth Season, 1949-1950] CHARLES MUNCH, Conductor RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin, Joseph de Pasquale Raymond Allard Concert-master Jean Cauhap6 Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Georges Fourel Theodore Brewster Eugen Lehner Gaston Elcus Contra-Bassoon Rolland Tapley Albert Bernard Emil Kornsand Boaz Piller Norbert Lauga George Zazofsky George Humphrey Louis Horns Cherkassky Arti^res Paul Willem Valkenier Harry Dubbs Charles Van Wynbergen Hans Werner James Stagliano Vladimir ResnikofE Principals Joseph Leibovici Jerome Lipson Siegfried Gerhardt Harry Shapiro Einar Hansen Harold Meek , Daniel Eisler Paul Keaney Norman Carol Violoncellos Walter Macdonald Carlos Pinfield Samuel Mayes Osbourne McConathy Paul Fedorovsky Alfred Zighera Harry Dickson Jacobus Langendoen Trumpets Minot Beale Mischa Nieland Georges Mager Hippolyte Droeghmans Roger Voisin Clarence Knudson Karl Zeise Principals Pierre Mayer Josef Zimbler Marcel Lafosse Manuel Zung Bernard Parronchi Harry Herforth Rene Voisin Samuel Diamond Enrico Fabrizio Victor Manusevitch Leon Marjollet Trombones James Nagy Leon Gorodetzky Flutes Jacob Raichman Lucien Hansotte Raphael Del Sordo Georges Laurent John Coffey Melvin Bryant James Pappoutsakis Josef Orosz John Murray Phillip Kaplan Lloyd Stonestreet -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

St. Louis Symphony Orchestra 2018/2019 Season at a Glance

Contacts: St. Louis Symphony Orchestra: Eric Dundon [email protected], (314) 286-4134 National/International: Nikki Scandalios [email protected], (704) 340-4094 ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 2018/2019 SEASON AT A GLANCE Season highlights include: • Music Director Designate Stéphane Denève conducts four weeks at Powell Hall, with a wide range of repertoire including works by Berlioz, Brahms, Lieberson, Mozart, Prokofiev, Ravel, Scriabin, Vaughan Williams, Wagner, and the SLSO premiere of Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Nyx. • Resident Conductor Gemma New leads the season-opening concert, including the SLSO premiere of Aaron Jay Kernis’ Musica celestis, along with Sibelius’ Finlandia and Elgar’s Enigma Variations. She leads a second concert including the SLSO premiere of Thomas Adès’ Three Studies from Couperin. • Marking the 50th anniversary of his SLSO debut, Conductor Laureate Leonard Slatkin leads two weeks of concerts, including a program of Leonard Bernstein’s “Kaddish” Symphony, Rachmaninoff’s First Piano Concerto, and the SLSO premiere of Loren Loiacono’s Smothered by Sky. His second program features Barber’s Symphony No. 1, Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, and the world premiere of an SLSO-commissioned work by Emmy Award-winning composer Jeff Beal, known for his music from the Netflix series House of Cards. • Conductors Karina Canellakis, Michael Francis, Gustavo Gimeno, Jakub Hrůša, and Matthias Pintscher make their SLSO debuts; returning guest conductors include Matthew Halls, Hannu Lintu, Jun Märkl, Cristian Măcelaru, Nicholas McGegan, Peter Oundjian, Nathalie Stutzmann, John Storgårds, Bramwell Tovey, and Gilbert Varga. • World premieres of two SLSO-commissioned works, Christopher Rouse’s Bassoon Concerto and a composition by Jeff Beal, along with a U.S.