Additional Educator Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pipe Band Jackets

Feather Bonnet Hackle and Cap Badge Guards Doublet Plaid Cross Belt Since 1950 Hardies have provided Pipe Bands around the world with a dedicated bespoke service. With over 50 years experience playing in Waist Belt Pipe Bands at all levels we have the knowledge and expertise to deliver Hand Made Heavy Weight Kilt uniforms to ensure your Pipe Band presents a smart and professional Military Doublet image for competitions, parades and public performances. Kilt Pin Our Piper range of uniform products have been designed specifically Horse Hair Sporran for Pipe Bands providing quality, durability and comfort. We offer two complete uniforms known as No.1 and No.2 dress. Hose Tops and Garter Flashes No.1 dress is a magnificent and grand uniform worn by Pipe Bands Spats featured in Tattoos and Highland Gatherings around the world. It will add a touch of class to any occasion such as Weddings, Corporate Brogues Events and Burns Suppers. Competition Pipe Bands today wear No.2 dress as it is comfortable to No.1 Dress wear and more affordable. This uniform offers many options to meet the needs of the modern day Pipe Band and it can be customised to This style of uniform is based on the include band and sponsors logos. requirements set out by the regiments within the British Army. Doublets can be decorated to show the rank and positions within a Pipe Band were we can advise what is appropriate. We offer two styles of doublets known as Military and Guards pattern, available in 19oz wool barathea in black, navy, bottle green or rifle green with silver or gold braid. -

Pipe Band Uniforms, Highland Dress & Accessories

PIPE BAND UNIFORMS, HIGHLAND DRESS & ACCESSORIES KILTS Made in Scotland by Leading Kiltmaker - 100% Worsted Cloth Gent’s Full Kilts Medium Worsted Cloth .............................8 yard Kilt .......$ 720.00 ..................................................................9 yard Kilt .......$ 750.00 Old & Rare Range - Medium Worsted .......8 yard Kilt .......$ 795.00 ..................................................................9 yard Kilt .......$ 825.00 Heavy Weight Stock Cloth .........................8 yard Kilt .......$ 765.00 ..................................................................9 yard Kilt .......$ 795.00 Special Weave - 16oz Cloth .......................8 yard Kilt .......$ 925.00 ..................................................................9 yard Kilt .......$ 990.00 Dancer’s Full Kilts ............................................................................. From $ 475.00 Ladies Semi-Kilt LTWT Wstd Cloth, up to 100 cm hips Machine Sewn ........................ From $ 350.00 Ladies Hostess Kilt Ankle Length 100% Worsted, up to 100cm hips. Machined ....................... $ 590.00 Straight Skirt - Reever cloth ........................................................................ $ 240.00 All of the above to measure - Delivery 8-10 weeks JACKETS Made to measure from Scotland - Delivery 8-10 weeks Several styles including Argyll, Crail, Montrose, Prince Charlie and Band Tunics to detail Plain Barathea Cloth, Crail & Argyll Style .................. $ 490.00 Tweed Crail & Argyll Style ....................................... -

In This Month's Hatalk

Issue 60, March 2011 Next issue due 16th March 2011 HATalk the e-magazine for those who make hats In this month’s HATalk... Millinery in Practice People at work in the world of hats. This month: Maxim - promoting millinery fashion in Japan. Hat of the Month A twisted toyo hat by Tracy Thomson. Focus on... Landelijke Hoedendag 2011 - National Milliner’s Day in the Netherlands. How to… Create a layered effect sinamay brim without a block. Plus – S in the A to Z of Hats, Letters to the Editor, this month’s Give Away and The Back Page. Published by how2hats.com click here to turn over i Issue 60 Contents: March 2011 Millinery in Practice People at work in the world of hats. This month: Maxim - a profile of this successful Japanese millinery firm. Hat of the Month Learn about this colourful hat and something about Tracy Thomson, who created it. Focus on... Landelijke Hoedendag 2011 - National Milliner’s Day in the Netherlands. How to... Create a layered effect sinamay brim without using a block. The A to Z of Hats... More hat words that start with S - continued from February. This Month’s Give Away A chance to win 25 HATalk Back Issues on CD! Letters to the Editor This month - a tip for getting your petersham headband sewn in neatly. The Back Page Interesting hat facts; books; contact us and take part! 1 previous page next page Maxim Millinery Fashion in Japan This month, our spotlight is on a millinery dynasty which has worked tirelessly for the last seventy years to bring hats to the forefront of Japanese fashion. -

The External Soul

Salem State University Digital Commons at Salem State University Graduate Theses Student Scholarship 2018-5 The External Soul Catherine Fahey Salem State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/graduate_theses Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Fahey, Catherine, "The External Soul" (2018). Graduate Theses. 31. https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/graduate_theses/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons at Salem State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Salem State University. Salem State University The Graduate School Department of English The External Soul A thesis in English by: Catherine Fahey Copyright 2018, Catherine Fahey Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2018 2 Table of Contents Faith ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 The Winter Witch ................................................................................................................................... 5 The Fool .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Collins Cove........................................................................................................................................... -

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

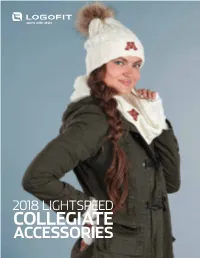

2018 Lightspeed Collegiate Accessories Content

2018 LIGHTSPEED COLLEGIATE ACCESSORIES CONTENT 2 PROGRAM 38 ACCESSORIES Adult 4 SUNWEAR Gift & Novelty Adult Youth 48 FLEECE Adult 12 TWO COLOR CLASSICS Youth Adult Youth 53 INFORMATION 26 CLASSICS 56 INDEX Adult Enhanced 58 CUSTOM CATALOG Youth PROGRAM How do you top LogoFit’s popular LightSpeed™ program? By making it even larger! We’ve expanded your favorite catalog for 2018 by adding more of what you’ve come to expect from us. 95+ high quality specialty headwear, gloves, scarves, and other hard to find styles are in stock and ready for immediate delivery. From sun and fashion headwear, to cozy cold-weather gear, we have you covered for every season, in every climate. Build your order by mixing any of the styles in the program, with minimums as low as 6 pieces per style/color. The possibilities are endless! Each product page reflects product order minimums and non-licensed pricing for easy reference. Take advantage of our LightSpeed program by placing your pre-season order with LogoFit now for fall delivery. With LightSpeed, your artwork purchased pre-season will be back-stocked at 50% of your initial order quantity and replenishment mid-season will be easy and quick with lower minimums and fast delivery. We deliver the product you want, where and when you want it. WHAT IS SONICWELDTM? LogoFit’s unique SonicWeld™ process results in unparalleled embellishment quality made possible by our own engineering. Our people and our equipment create the most consistent and highest quality embroidered weld designs in the industry - even on the most difficult to embellish styles. -

Practical Yet Picturesque Aire Winter's Hats

PRACTICAL YET PICTURESQUE AIRE WINTER'S HATS THE FUR TRIMMED TOQUE AND WIDE-BRIMMED CANO¬ TIER ARE APPROVED BY FASHION, WHICH MAIN¬ TAINS A NEW DIGNITY BY ESCHEWING THE ECCENTRIC IN HATS AND GOWNS. IVingliki ' this tamp» 11 It et hak sail* lightly BOOBS (i rimul.-i BtJ ./.>. |i*»' <¦ -'¦ '».». '//'.' large black rein t ranotier, of el'armuigUi /«> ka» ermine far its erotcn, and a» toU à ration a » scalloped at the edges, may be new¬ er, and certainly more fancitui, than the other designs, but what we want now is something practical, and the .4 àanv.n toan» .**¦ one, both in its color¬ skirt that is not voluminous answers and in ing, ir/ü'r- ermine and black whys, the demand perfectly. It is weara¬ c/ the mounts at each ble indoors with the ever useful fide ¦.¦n'. blouse, and may be made nov. I in The coloring of th» yirnvd hat is éiatine- appearance by a high corselet, pret¬ blaek rclvct brim it a tily braided, and touched with color, dull gold crou-,1, covered by a tomato not all the way around the waist, hut color 'J tissu», »kumk frinyed. where the ornamentation is found to be most effective. n.v mum Ascoi/GH. CtftéUtUte and Velvets drought Out in THK latest millinery models cr I old Weather. ated by Parisian artists are Colder weather has brought soft picturesque as they a corduroys and velveteens, as well as lovely. many forms of velvets, into wear, in¬ a decorative moire all the desigi cluding design. Nearly prominent Dark but lustrous colors are liked, are becoming and practical. -

Autumn Winter 2021/22

AUTUMN WINTER 2021/22 cover: CLOCHE, wool felt soft, M21506, this page: CAP, lambskin, P21601, following page, left: BUCKET HAT, melusine felt, M21514, right: BUCKET HAT, melusine felt, M21515 AUTUMN WINTER 2021/22 BIG HUG Where have you gone, you intimate, stormy, friendly, romantic, comforting hugs? We have missed you so much. The autumn winter 2021/22 collection invites you to join it in a big, all-enveloping hug. The hats are fluffy and light as a feather, voluminous, as soft and padded as cotton wool. You can wrap yourself up in them, squeeze them heartily, literally crawl into them for comfort. In return they will hug you back and wrap themselves protectively around you. These are materials that invite cuddles, to feel, to sense, to lose ourselves in them. Because it’s simply impossible to keep your hands off cashmere loden, melusin felt, soft sherpa wool and thickly padded fabrics. The pieces in this collection are approachable, easy to grasp, and just as easy to experience and wear. This feels so good. Wo seid ihr geblieben, ihr innigen, stürmischen, freund- schaftlichen, romantischen, tröstenden Umarmungen? Wir haben euch so vermisst. Die Modelle der Kollektion Herbst Winter 2021/22 laden zu einer großen Umarmung ein. Sie sind flauschig und federleicht, watteweich gepolstert und mit Volumen gefüllt. Man kann sich darin einwickeln, sie herzhaft drücken, förmlich in sie hineinkriechen. Sie sind uns nahe und legen sich schützend um uns. Da sind Materialien, die zum Kuscheln einladen, zum Spüren, Fühlen, sich darin verlieren. Denn von Kaschmir- loden, Melusinfilz, weicher Sherpa-Wolle und dick gepolster- ten Stoffen kann man einfach nicht die Finger lassen. -

Canadian Armed Forces Dress Instructions

National A-DH-265-000/AG-001 Defence CANADIAN ARMED FORCES DRESS INSTRUCTIONS (English) (Supersedes A-AD-265-000/AG-001 dated 2017-02-01) Issued on Authority of the Chief of the Defence Staff OPI: DHH 2017-12-15 A-DH 265-000/AG-001 FOREWORD 1. A-DH-265-000/AG-001, Canadian Armed Forces Dress Instructions, is issued on authority of the Chief of Defence Staff. 2. The short title for this publication shall be CAF Dress Instructions. 3. A-DH-265-000/AG-001 is effective upon receipt and supersedes all dress policy and rules previously issued as a manual, supplement, order, or instruction, except: a. QR&O Chapter 17 – Dress and Appearance; b. QR&O Chapter 18 – Honours; c. CFAO 17-1, Safety and protective equipment- Motorcycles, Motor scooters, Mopeds, Bicycles and Snowmobiles; and 4. Suggestions for revision shall be forwarded through the chain of command to the Chief of the Defence Staff, Attention: Director History and Heritage. See Chapter 1. i A-DH 265-000/AG-001 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................... i CHAPTER 1 COMMAND, CONTROL AND STAFF DUTIES ............................................................. 1-1 COMMAND ...................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 CONTROL ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Ahead Corporate HEADWEAR & ACCESSORIES SECOND EDITION

Ahead Corporate HEADWEAR & ACCESSORIES SECOND EDITION 20 19 WWW.AHEADCORPORATE.COM INTRODUCING SONICWELD! SONIC BOOM! Use AHEAD’s new SONICWELD technique to add POP to your logo with texture, dimension, & dynamic color. This proprietary technique offers a modern alternative to traditional embroidery. ORNAMENTATION - MIX IT UP Nobody has more ways than AHEAD to help you present your logo in so many eye catching, and innovative ways. With variety like this, Ahead can offer you a multitude of was to transform and present your logo. Direct Embroidery Name Drop Name Drop w/ Logo 3D/Bounce Embroidery Printed Label-Coolmax Printed Label-Canvas 3D Printed Vintage Label Custom Vin Therm Vintage Label w/Embroidery 3D Printed Label w/Embroidery Applique W/ Embroidery Open Edge Printed Applique Woven Applique Label Rubber Applique Sonic Weld Grafix Weld *Please contact your AHEAD Sales Representative for pricing. TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 MODERN TREND HATS 37 KATE LORD 50 MONEY CLIPS/HAT CLIPS/BAG TAGS 06 CLASSIC COTTONS 41 PRIVATE LABEL 51 STOCK LEATHER/POKER CHIPS 13 FITTED 42 PERSONALIZATION 52 TOWELS/BLANKETS/BAGS 14 PERFORMANCE 43 T-SHIRT CAP COMBO 53 CHROMAPLATE 24 CASUALS 44 TOURNAMENT GIFT PACKS 54 APPAREL 29 VISORS 47 CORPORATE ACCESSORIES 56 T-SHIRTS 32 BRIMMED HATS 48 BALLMARKER/COMMEMORATIVE 58 PANTONE MATCHES 34 KNITS 49 DIVOT TOOLS 59 INDEX Icon Legend GRAFIXWELD SONIC WELD SO MANY WAYS TO GET AHEAD! LADIES’ APPAREL MEN’S APPAREL HEADWEAR ACCESSORIES & GIFTS CORPORATE HEADWEAR TEAM/COLLEGIATE HEADWEAR ASI#33220 PPAI#552592 EVEN MORE REASONS TO GET AHEAD! Corporate Social Responsibility AHEAD, LLC is committed to a platform corporate responsibility, striving for business solutions that integrate financial responsibility with long term social and environmental perspectives. -

13, 53, 56-57 Imogene Shawl. Knits: 13, 53, 57-58 Corsage Scarf

Knits Index Through Knits Summer 2017 Issue abbreviations: F = Fall W = Winter Sp = Spring Su = Summer This index covers Knits magazine, and special issues of Crochet, Knit.Wear, Knit.Purl and Knitscene magazine before they became independent journals. To find an article, translate the issue/year/page abbreviations (for example, “Knitting lace. Knits: Su06, 11” as Knits, Summer 2006, page 11.) This index also includes references to articles and patterns on the website, some of which are for subscribers only. Some of these are reprinted from the magazine; others appear only on the website. The first issue of Crochet magazine appeared in Fall, 2007. This index includes all of the special issues of Knits magazine devoted to crochet before Crochet became its own publication. After Spring, 2007, Crochet issues do not appear in this index, but can be found in the Crochet index. For articles indexed before that time, translate “City Stripes. Knits (Crochet): special issue F06, 90” as the special issue of Knits, labeled “Interweave Crochet,” Fall 2006, p. 90. The first issue of Knitscene magazine as an independent journal appeared in Spring, 2011. This index includes all of the special issues of Knitscene magazine before Knitscene became its own publication. After Spring, 2011, Knitscene issues do not appear in this index, but can be found in the Knitscene index. For articles indexed before that time, translate “City Stripes. Knits (Knitscene): special issue F06, 90” as the special issue of Knitscene, labeled “Interweave Knitscene,” Fall 2006, p. 90. The first issue of Knit.wear as an independent journal appeared in Spring, 1017. -

How Many Names for Hats Can You Find?

How many names for hats can you find? D A D E L C O G R O O N S H E W K E G V D L F A S C I N A T O R Y J R S F O I T M T A I I B I B N U J B B C C S G U R J L O S S Y G K D Y H M B K R N M O A Q E Z F W U F E Z Y L B I H R T W E C O O N S K I N C A P C B E G E H X A C T O Q U E N F B E R E T O W Q E P R V U O B E A N I E D M P I C T U R E S I D L T T A F B O H A R D H A T C O A Q O R B U R P P S Z Y X O O R C V P T O R K C E B O W L E R A L H H U N G P D S T E T S O N C A P A J N A I B N F F M L K E I V I T D E P E A C H B A S K E T A S C O T ASCOT A hard style of hat, usually worn by men, dating back to the 1900s.