Australia and New Zealand Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Layer Cake Fact Tech Sell Sheet Working File MASTER.Indd

SHIRAZ SOUTH AUSTRALIA | VINTAGE 2015 Winemaker Notes For our Shiraz, we pull from vineyards in McLaren Vale and the Barossa Valley— from the sandy-soiled blocks on the sea coast of Gulf St. Vincent to the Terra Rosa- based, tiny-berried, wind-blown rolling hills in the Barossa Zone. The microclimates give us a broad array of fl avors to blend into a complex, rich, full wine. Vineyard Notes South Australia is arguably one of the top Shiraz-growing regions of the world. Within SA, the McLaren Vale and the Barossa are the most diverse and historic sub-regions, with vines dating back to the 1830s. The microclimates within these areas are what give Layer Cake Shiraz its complexity. The McLaren Vale is bordered on one side by water and the other by an ancient mountain range – Gulf St. Vincent and the Adelaide Hills, in this case. The Vale is moderated in temperature by the sea, as the warm air gets trapped in pockets of the undulating hills. These blocks have deeper soils and produce wines with big, mouth-fi lling fruit. The Barossa has shallow red soils with limestone underneath and is directly in the path of the brutal heat and dust storms that emanate from the Great Australian Outback. The vines struggle to survive, producing tiny berries with thick skins and wines with big structure and intensity. Tasting Notes The aromas of cocoa, warm spice and dark fruit are very powerful from the fi rst whiff. In the mouth, the wine is layered with rich blackberry, dark cherries and hints of dark, creamy chocolate ganache. -

Fleurieu Zone

WINEGRAPE UTILISATION AND PRICING SURVEY 2005 63 Fleurieu zone (other) 64 FLEURIEU ZONE (OTHER) VINTAGE OVERVIEW The long dry and mild finish to the ripening season created an ideal environment for the development of intense colour and flavours. The Fleurieu zone (other) includes the GI regions Southern Fleurieu, Currency Creek and Harvest began two weeks earlier than 2004 with crops being slightly above average across Kangaroo Island, as well as any other plantings in the zone that are outside the major regions all white varieties. Continued favourable ripening conditions through February and March of McLaren Vale and Langhorne Creek. Because of the small size of the GI regions, they meant that there was no rest between whites and reds, with all red varieties ripening two to are not reported separately. However, tonnage and forecast data are available for these three weeks earlier than the previous vintage. Crop yields in Cabernet Sauvignon were the regions on request from the Board. most affected by a less than average set while Merlot was slightly above average in yield. All other red varieties produced average yields. Vintage report - Currency Creek Early indications are that 2005 has the hallmarks of a great vintage. Intense flavour and It was a near perfect growing season in Currency Creek. There were soaking spring rains colour in the reds and an abundance of fruit balanced with natural acidity in the whites. though October to November and soil moisture levels were adequate right up until the David Watkins beginning of December. Fruit set in the red varieties was affected by the cooler conditions. -

3.2 Mb PDF File

The Australian Wine Research Institute 2008 Annual Report Board Members The Company The AWRI’s laboratories and offices are located within an internationally renowned research Mr R.E. Day, BAgSc, BAppSc(Wine Science) The Australian Wine Research Institute Ltd was cluster on the Waite Precinct at Urrbrae in the Chairman–Elected a member under Clause incorporated on 27 April 1955. It is a company Adelaide foothills, on land leased from The 25.2(d) of the Constitution limited by guarantee that does not have a University of Adelaide. Construction is well share capital. underway for AWRI’s new home (to be com- Mr J.F. Brayne, BAppSc(Wine Science) pleted in October 2008) within the Wine Innova- Elected a member under Clause 25.2(d) The Constitution of The Australian Wine tion Cluster (WIC) central building, which will of the Constitution (until 12 November 2007) Research Institute Ltd (AWRI) sets out in broad also be based on the Waite Precinct. In this new terms the aims of the AWRI. In 2006, the AWRI building, AWRI will be collocated with The Mr P.D. Conroy, LLB(Hons), BCom implemented its ten-year business plan University of Adelaide and the South Australian Elected a member under Clause 25.2(c) Towards 2015, and stated its purpose, vision, Research and Development Institute. The Wine of the Constitution mission and values: Innovation Cluster includes three buildings which houses the other members of the WIC concept: Mr P.J. Dawson, BSc, BAppSc(Wine Science) Purpose CSIRO Plant Industry and Provisor Pty Ltd. Elected a member under Clause 25.2(d) of the To contribute substantially in a measurable Constitution way to the ongoing success of the Australian Along with the WIC parties mentioned, the grape and wine sector AWRI is clustered with the following research Mr T.W.B. -

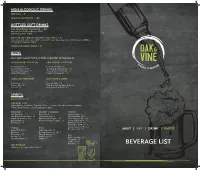

Beverage List

NON ALCOHOLIC DRINKS RED BULL | 5 LEMON LIME BETTERS | 4.5 BOTTLED SOFT DRINKS SAN PELLEGRINO SPARKLING | 5.5 Aranciata Rossa (Blood Orange) 330ml Limonata (Lemon) 330ml BOTTLED SOFT DRINKS AND BOTTLED JUICES | 5 Coca cola, Sprite, Coke Zero, Orange Juice,Pineapple Juice, Apple Juice, Bottlled water (400ml), Bottled sparkling water (250ml) SPARKLING WATER 750ML | 8 BEERS Ask your waiter for our wide selection of tap beers. IMPORTED BOTTLED BEERS CRAFTED BOTTLED BEERS Kirin (Japan) | 9.5 Lazy Yak Pale Ale | 10 Corona (Mexico) | 8.5 Mountain Goat Steam Ale | 10 Heineken (Germany) | 9.5 Stone & Wood Pacific Ale | 10 Singha (Thailand) | 8 Furphy Refreshing Ale | 9.5 LOCAL BOTTLED BEERS LIGHT BEER & CIDER Carlton Dry | 8 Cascade light | 7.5 Crown Lager | 8 Dirty Granny Craft Apple Cider | 9 Iron Jack | 8 Strongbow Pear Cider | 5.5 SPIRITS BAISC SPIRITS | 8 LIQUEURS | 9.5 Midori, Kahlua, Frangelico, Cointreau, Baileys, Tia Maria, Drambuie, Galiano sambuca (White, Black, Vanilla), Sierra Tequilla (silver, gold) BOURBON BRANDY & COGNAC WHISKY Jack Daniel No. 7 | 9 Remy Brandy | 8 Jameson Irish | 9 Jack Daniel Single barrel | 12 St Agnes Brandy | 9 Canadian Club | 8.5 Sounthern Comfort | 8.5 Hennessey Vs Cognac | 10 Chivas Regal 12YR | 10 Makers Mark | 9 Courvoisier Vsop Congnac | 13 Chivas Regal 18YR | 15 Wild Turkey | 10 Dilwhinnie 15YR | 13 Glenfiddich 12YR | 11.5 Glenmorangie 10YR | 12 VODKA RUM Bowmore Islay | 14 Smirnoff Red | 8.5 Hvana Especial | 10 MEET | EAT | DRINK | ENJOY Belvedere | 11 Captain Morgan Spiced | 9 Grey Goose | 14 Bacardi -

Fleurieu Zone

SA Winegrape Crush Survey 2020 Regional Summary Report Fleurieu other Inc Southern Fleurieu and Kangaroo Island Wine Australia July 2020 Fleurieu other Vintage overview Fleurieu other in this report includes the GI regions Southern Fleurieu and OVERVIEW OF VINTAGE STATISTICS Kangaroo Island, as well as any other plantings in the zone that are The reported crush of winegrapes from Fleurieu other was 2920 tonnes in outside any GI regions in the Fleurieu zone. The total area of vines 2020, down by 15 per cent compared with the 2019 reported crush of included in this definition is 870 hectares. 3452 tonnes. Over the past five years (up to 2019), the average crush for Fleurieu other has been 3478 tonnes, making this year’s crush 16 per cent below the five-year average. There were 24 respondents to the survey who reported crushing grapes from Fleurieu other in 2020, compared with 27 in 2019. The total estimated value of winegrapes from Fleurieu other in 2020 was $3.2 million compared with $3.3 million in 2019 – a 5 per cent decrease. The decrease in production was partly offset by an overall increase in the average purchase value of grapes, which increased by 11 per cent from $976 in 2019 to $1081 per tonne. There were increases in average prices for the three largest varieties: Shiraz up by 7 per cent to $1249 per tonne, Sauvignon Blanc up 30 per cent to $990 per tonne and Pinot Gris/Grigio up by 17 per cent to $986 per tonne. The price dispersion data shows a narrow range of purchase prices, with 92 per cent of red grapes and 88 per cent of white grapes purchased at between $600 and $1500 per tonne. -

Wine Grape Market Study

Wine grape market study Interim report June 2019 accc.gov.au Australian Competition and Consumer Commission 23 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2601 © Commonwealth of Australia 2019 This work is copyright. In addition to any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all material contained within this work is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence, with the exception of: the Commonwealth Coat of Arms the ACCC and AER logos any illustration, diagram, photograph or graphic over which the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission does not hold copyright, but which may be part of or contained within this publication. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Director, Content and Digital Services, ACCC, GPO Box 3131, Canberra ACT 2601, or [email protected]. Table of contents Glossary................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 8 Context of the market study............................................................................................ 8 Issues and implications ................................................................................................. -

Wine Grape Market Study

Wine grape market study Interim report June 2019 accc.gov.au Australian Competition and Consumer Commission 23 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2601 © Commonwealth of Australia 2019 This work is copyright. In addition to any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all material contained within this work is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence, with the exception of: the Commonwealth Coat of Arms the ACCC and AER logos any illustration, diagram, photograph or graphic over which the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission does not hold copyright, but which may be part of or contained within this publication. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Director, Content and Digital Services, ACCC, GPO Box 3131, Canberra ACT 2601, or [email protected]. Table of contents Glossary................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 8 Context of the market study............................................................................................ 8 Issues and implications ................................................................................................. -

Illustrative Projects of 2012 - 2013

Illustrative projects of 2012 - 2013 H ighlights 2012 - 2013 $21 million water Jam Factory to infrastructure be established in Future Leaders project received the Barossa $10.7 million Programme future support 107 jobs created Be Consumed – Region wins in business Barossa $6 priority within assisted Million Tourism NBN 3 year Campaign rollout Place Barossa Career Management SService trains & 536 Businesses for Township & refocusses ffor assisted renewal transition iIndustries Regional Township Development Economic South Australia Development Conference workshops TAFE Virtual Thinking Barossa Enterprise – Big Ideas for partner Innovating High H ighlights 2012 - 2013 82 workshops Young people in 1391 agriculture Events strategy participants network established 62 businesses assisted to Cycle Tourism innovate Strategy Disability & Live Music 12 Tourism Aged Care Thinker in Infrastructure Cluster Residence projects assisted established to win grant funding Workforce audit World Heritage Regional for transferable status – project Development skills assists 135 management Grants - businesses group Gawler & Light Northern FACETS Barossa: Adelaide Plains Broadband linked Horticultural National multi-site Conference lights Futures Outcome 1: Community and Economic Development Infrastructure: The Greater Gawler Water Reuse Scheme RDA Barossa has collaborated with The Wakefield Group and regional councils in a strategic project to drive economic diversity and sustainable water resources into the future under the South Australian Government’s 30 Year Plan for Greater Adelaide. It is forecast that the population will increase by 74,400 by 2040 and employment by 38,500 jobs. The focus for the population growth is Greater Gawler/Roseworthy and the employment is led by intensive agriculture, its processing and distribution with a new irrigation area proposed north of Two Wells in the west with other areas adjacent to Gawler intensifying to increase production. -

Australian Vintage Ltd. June 2018 Results 29Th August 2018 Australian Vintage Ltd

Australian Vintage Ltd. June 2018 Results 29th August 2018 Australian Vintage Ltd. June 2018 Results Disclaimer The presentation has been prepared by Australian Vintage Limited the industry, countries and markets in which AVG operate. They also (ACN 052 179 932) (“AVG”) (including its subsidiaries, affiliates and include general economic conditions, exchange rates, interest rates, the associated companies) and provides general background information regulatory environment, competitive pressures, selling price, market about AVG’s activities as at the date of this presentation. The demand and conditions in the financial markets which may cause information does not purport to be complete, is given in summary and objectives to change or may cause outcomes not to be realised. may change without notice. None of AVG (and their respective officers, employees or agents) (the This presentation is not intended to be relied upon as advice to Relevant Persons) makes any representation, assurance or guarantee as investors or potential investors and does not take into account the to the accuracy or likelihood of fulfilment of any forward looking investment objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular statement or any outcomes expressed or implied in any forward looking investor. These should be considered, with or without professional statements. The forward looking statements in this presentation reflect advice, when deciding if an investment is appropriate. The presentation views held only at the date of this presentation. Except as required by does not constitute or form part of an offer to buy or sell AVG applicable law or the ASX Listing Rules, the Relevant Persons disclaim securities. any obligation or undertaking to publicly update any forward looking statements, whether as a result of new information or future events. -

National Vintage Report 2019 Wine Australia 1 Figure 1: Historical Australian Winegrape Crush 2009–2019

Wine Australia for National Vintage Australian Wine Report 2019 At a glance summary • The Australian winegrape crush in 2019 was 1.73 million tonnes – a decrease of 3 per cent from the 2018 harvest • The crush was very close to the long-term average of 1.75 million tonnes • Warm regions decreased less than cool/temperate regions: − The crush in cool/temperate regions decreased by 5 per cent − The crush in warm regions decreased by 2 per cent − Warm inland regions increased their share of the overall crush from 72 per cent to 73 per cent • Red varieties fared better than white varieties in terms of production: − Red varieties overall up by 2 per cent − White varieties down by 8 per cent − Shiraz down by 2 per cent − Cabernet Sauvignon up 3 per cent − Merlot up 13 per cent − Chardonnay down 12 per cent • Average winegrape purchase prices increased across the board: − The average across all varieties increased by 9 per cent to $664 per tonne – the highest since 2008 − The average across all red varieties increased by 9 per cent to $845 per tonne − The average across all white varieties grew by 4 per cent to $462 per tonne • The total estimated value of the crush increased by 6 per cent to $1.17 billion, with the lower tonnages offset by higher average prices • The proportion of winery grown fruit was up slightly to 32 per cent of the 2019 crush. Overview of the 2019 winegrape crush The 2019 winegrape crush is estimated to be 1.73 million in 2019 across all vineyards was 11.8 tonnes per hectare, tonnes, based on responses received by the National compared with 12.2 tonnes per hectare in 2018 and 13.6 Vintage Survey 20191. -

Barossa Facilitator Guide

BAROSSA FACILITATOR GUIDE AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED EDUCATION PROGRAM The comprehensive, free education program providing information, tools and resources to discover Australian wine. To access course presentation, videos and tasting tools, as well as other programs, visit Wine Australia www.australianwinediscovered.com supports the responsible service of alcohol. For enquiries, email [email protected] Barossa / Facilitator guide BAROSSA Kalleske Wines, Barossa Wines, Kalleske AUSTRALIAN WINE DISCOVERED Troye Kalleske, Troye Australia’s unique climate and landscape have fostered a fiercely independent wine scene, home to a vibrant community of growers, winemakers, viticulturists, and vignerons. With more than 100 grape varieties grown across 65 distinct wine regions, we have the freedom to make exceptional wine, and to do it our own way. We’re not beholden by tradition, but continue to push the boundaries in the pursuit of the most diverse, thrilling wines in the world. That’s just our way. Barossa / Facilitator guide AUSTRALIA NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND WESTERN AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEW SOUTH WALES VICTORIA BA RO SS A 0 500 TASMANIA Kilometres SOUTH AUSTRALIA BaRO SS a NEW SOUTH WALES V a LL EY EDEN ADELAIDE V a LL EY VICTORIA Barossa / Facilitator guide BAROSSA: HISTORY AND Encompassing Barossa Valley and Eden Valley, Barossa is one of EVOLUTION Australia’s most historic and prominent wine regions. - Rich history dating back to 1840s - Community includes long- established wine families and younger artisan and boutique producers - Diversity of soils, climate and topography - Some of the world’s oldest grapevines - Strong culinary culture and gourmet local produce VIDEO BAROSSA: HISTORY AND EVOLUTION Now is a great time to play the The undulating Barossa region is one of Barossa loop video in the background, the most historic wine-producing areas in as you welcome people. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2004 Table of Contents

ACN o52 179 932 ANNUAL REPORT 2004 Table of Contents 3 Chairman’s Report 5 Managing Director’s Report - 2004 The expanded company takes shape. 8 Company Profile 10 Corporate Governance Statement 16 Shareholders’ Information 17 Directors’ Report 22 Independent Audit Report 24 Financial Statements Highlights Directors David S Clarke The successful merger and seamless integration of the Ian D Ferrier Miranda businesses to create: Nicholas F Greiner Perry R Gunner Australia’s fifth largest wine company. Christopher L Harris Brian J McGuigan Australia’s second largest listed pure wine company with a market capitalisation in excess of $500m at Company Secretary 30th June 2004 Julie Thomas Net profit increase of 25% Chief Financial Officer Michael H Noack Basic earnings per Share increase of 15% Auditors Dividend per Share increase of 18% Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu 190 Flinders Street ADELAIDE SA 5000 Bankers National Australia Bank 33/500 Burke Street MELBOURNE VIC 3000 Share Register Computershare Registry Services Pty Ltd 115 Grenfell Street ADELAIDE SA 5000 Ph: +61 8 8236 2300 Fax: +61 8 8236 2305 Head Office 170 Greenhill Road PARKSIDE SA 5063 Notice of Annual General Meeting Ph: +61 8 8172 8333 Fax: +61 8 8357 8544 The Annual General Meeting of Shareholders of Registered Office McGuigan Simeon Wines Limited will be held at 170 Greenhill Road Masonic Centre, Sydney PARKSIDE SA 5063 on 18 November 2004 at 3:00pm. Ph: +61 8 8172 8333 A formal notice of the meeting and Proxy Form is Fax: +61 8 8357 8544 enclosed with this Annual Report. Web: www.mswl.com.au 2 McGuigan Simeon Wines Limited - Annual Report 2004 McGuigan Simeon Wines Limited - Annual Report 2004 3 Chairman’s Report costs, winery costs, packaging, In the year ended 30 June 2004, the Company’s distribution and overheads; net profit after tax rose to $40.2 million, a 25% • a strategy of having a percentage of increase over the 2003 result.