Capitol-Hill-Brochure.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capitol Hill Guide Welcome

The Van Scoyoc Companies Capitol Hill Guide Welcome Welcome to Washington and the Van Scoyoc Companies. I hope you’ll find this guide useful during your visit to Capitol Hill. Our Country’s forefathers enshrined in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution the people’s right “peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” They considered this right of equal importance with freedom of religion and freedom of the press. Thousands of Americans visit their elected representatives in the House and the Senate each year, providing Members of Congress and the Administration with vital insights into the Country’s needs and fears and wishes for the future. Unfortunately, many Americans today don’t appreciate this right – and this privilege – they have to influence government by making their views known, either directly or through agents and associations. The Founding Fathers knew that a great nation grew out of a vigorous competition of ideas and interests, and they designed our Government to accommodate conflicts, not quash them. We at the Van Scoyoc Companies have always believed that our primary role was to help our clients find honorable and effective ways to make their arguments known to those in power. Please don’t hesitate to ask anyone in our firms for something you may need during your visit to Washington. We don’t pretend to have the answer to every question, but I guarantee you that when we don’t, we know how to find it. Regards, Contents ciate sso s I a nc c o • y V Stu’s Welcome 2 o S C c o s n n s a Map of Capitol Hill 3 u v l • t c i a n Hints for Visiting Congressional Offices 4 p g i I t n o c • l D Useful Contacts 5 e c c isions In Restaurant Map 6 Recommended Restaurants 7 This guide was created for the convenience and sole use of clients and potential clients of the Van Map of Places to Visit 8 Scoyoc Companies. -

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

The Capitol Building

CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER TEACHERTEACHER LLESSONESSON PLANLAN The Capitol BuildiNg Introduction The Capitol is among the most architecturally impressive and symbolically important buildings in the world. The Senate and the House of Representatives have met here for more than two centuries. Begun in 1793, the Capitol has been built, burnt, rebuilt, extended, and restored; today, it stands as a monument not only to its builders but also to the American people and their government. As George Washington said, public buildings in the Capitol city “in size, form, and elegance, should look beyond the present day.”1 This activity features images of the U.S. Capitol building — architectural plans and artistic renderings from its original design and subsequent expansion. Examining these images, students engage in class discussion and individual reflection, considering how a building itself might serve as a symbol and monument. Then, they draft images that capture their own interpretation of how a Capitol building should look. While intended for 8th grade students, the lesson can be adapted for other grade levels. 1 The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745–1799. John C. Fitzpatrick, Editor., Philadelphia, March 8, 1792. 1 TEACHER LESSON PLAN: THE CAPITOL BUILDING CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER TEACHER LESSON PLAN Estimated Time One to two class sessions National Standards National Standards for Civics and Government Content Standards, grades 5–8 II — What are the Foundations of the American Political System (D.1) United -

Early New York Houses (1900)

1 f A ':-- V ,^ 4* .£^ * '"W "of o 5 ^/ v^v %-^v V^\^ ^^ > . V .** .-•jfltef-. %.^ .-is»i-. \.^ .-^fe-. *^** -isM'. \,/ V s\ " c«^W.».' . o r^0^ a? %<> **' -i v , " • S » < •«. ci- • ^ftl>a^'» ( c 'f ^°- ^ '^#; > ^ " • 1 * ^5- «> w * dsf\\Vv>o», . O V ^ V u 4- ^ ° »*' ^> t*o* **d« vT1 *3 ^d* 4°^ » " , ^o .<4 o ^iW/^2, , ^A ^ ^°^ fl <^ ° t'o LA o^ t « « % 1 75*° EARLY Z7Ja NEW YORK HOVSEvS 1900 EARLY NEW YORK HOVSES WITH HISTORICAL 0^ GEN- EALOGICAL NOTES BY' WILLIAM S.PELLETREAV,A.M. PHOTOGRAPHS OFOLDHOVSES C-ORIGINAL ILLVSTRATIONSBY C.G.MOLLER. JR. y y y v v v v v v v <&-;-??. IN TEN PARTS FRANCIS P.HARPER, PVBLIS HER NEW YORK,A.D.jQOO^ * vvvvvvvv 1A Library of Coi NOV 13 1900 SECOND COPY Oeliv. ORDER DIVISION MAR. 2 1901 fit,* P3b ..^..^•^•^Si^jSb;^^;^^. To the memory of WILLIAM KELBY I^ate librarian of the New York Historical Society f Whose labors of careful patient and successful research w have been equalled by few—surpassed by none. w Natvs, Decessit, MDCCCXU MDCCCXCVIII ¥ JIT TIBI TERRA LEVIJ , ^5?^5?^'55>•^••^•^=^,•^•" ==i•'t=^^•':ft>•' 1 St. Phuup's Church, Centre; Street Page 1 V 2 Old Houses on " Monkey Hill " 3/ 3 The Oldest Houses in Lafayette Place 7 / 4 The Site of Captain Kidd's House ll • 5 Old Houses on York Street 15/ 6 The Merchant's Exchange 19 V 7 Old Houses Corner of Watts and Hudson Streets 23 </ 27v/ 8 Baptist Church on Fayette Street, 1808 . 9 The in Night Before Christmas" was House which "The •/ Written 31 10 Franklin Square, in 1856 35^ 11 The First Tammany Hall 41 </ 12 Houses on Bond Street 49^ 13 The Homestead of Casper Samler 53/ 14 The Tank of the Manhattan Water Company 57 ^ 15 Residence of General Winfield Scott 61 l/ 16 The Last Dwelling House on Broadway, (The Goelet Mansion) 65^ \/ 17 Old Houses on Cornelia Street , n 18 The Last of LE Roy Place 75*/ 19 Northeast Corner of Fifth Avenue and Sixteenth Street . -

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland Founding the Proprietary Colony The founding and establishment of the propriety government of Maryland was the product of competing factors—political, commercial, social, and religious. It was intertwined with the history of one family, the Calverts, who were well established among the Yorkshire gentry and whose Catholic sympathies were widely known. George Calvert had been a favorite of the Stuart king, James I. In 1625, following a noteworthy career in politics, including periods as clerk of the Privy Council, member of Parliament, special emissary abroad of the king, and a principal secretary of state, Calvert openly declared his Catholicism. This declaration closed any future possibility of public office for him. Shortly thereafter, James elevated Calvert to the Irish peerage as the baron of Baltimore. Calvert’s absence from public office afforded him an opportunity to pursue his interests in overseas colonization. Calvert appealed to Charles I, son of James, for a land grant.1 Calvert’s appeal was honored, but he did not live to see a charter issued. In 1632, Charles granted a proprietary charter to Cecil Calvert, George’s son and the second baron of Baltimore, making him Maryland’s first proprietor. Maryland’s charter was the first long-lasting one of its kind to be issued among the thirteen mainland British American colonies. Proprietorships represented a real share in the king’s authority. They extended unusual power. Maryland’s charter, which constituted Calvert and his heirs as “the true and absolute Lords and Proprietaries of the Region,” might have been “the best example of a sweeping grant of power to a proprietor.” Proprietors could award land grants, confer titles, and establish courts, which included the prerogative of hearing appeals. -

White Miles..., 139 Free Black Females

SCHOOLS OF THE COLORED POPULATION. PERIOD I.--1O1-1861. The struggles of the colored people of tilh District of Columbia, in securing for themselves thli means of education, furnish a1 very instructive chapter in the history of schools. Their courage and resolution were such, in the midst of their own great ignorance and strenuous opposition from without, that a permanent record becomes an act of justice to them. In the language of Jefferson to Banneker, tile black astronomer, it is ia publication to which their "whole color hlas a right for their justification against thle doubts which have been entertained of them." 'Though poor, proscribed anId unlettered, they founded, in their lumble way, an institution for the education of their children within less tlian two years after tile first school- house of whites was luilt in lie city. T'lie sentiment against the eduention of the colored classes wasViiucli less rigorous in tih( early history of the capital than it was a third of it century later. Tlie free colored people were sometimes even encouraged, to a limited extent, in their efforts to pick upl some fragments of knowledge. They were taught in tile Sunday schools and evening schools occasionally, and respectable mulatto families were in many cases allowtel to attend, with white children, the private schools and academies. There are scores of colofcd mlen and women still living in this District wilo are decently educated, and who iovcer went to any but white schools. Th'ler are also wilite men and women still alive here, wlih wnilt to school in this city and in Georgetown withl colored children and felt no offence. -

The GW Law Student's Housing Guide

The GW Law Student’s Housing Guide: Created by Students for Students A publication of the GW Law Student Ambassadors The George Washington University Law School Washington, D.C. Table of Contents WASHINGTON, D.C. Foggy Bottom and the Surrounding Area ..............................................................4 Adams Morgan ...........................................................................................................18 Capitol Hill ...................................................................................................................19 Cleveland Park/Woodley Park ................................................................................20 Columbia Heights .....................................................................................................21 Downtown ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������22 Dupont Circle �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������23 Georgetown ...............................................................................................................24 Logan Circle ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������25 Tenleytown/American University ............................................................................26 U Street �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������27 Van Ness ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������28 -

QUES in ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1

[email protected] - QUES IN ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1 Faculty: Zeynep Çelik Alexander, Reinhold Martin, Mabel O. Wilson Teaching Fellows: Oskar Arnorsson, Benedict Clouette, Eva Schreiner Thurs 11am-1pm Fall 2016 This two-semester introductory course is organized around selected questions and problems that have, over the course of the past two centuries, helped to define architecture’s modernity. The course treats the history of architectural modernity as a contested, geographically and culturally uncertain category, for which periodization is both necessary and contingent. The fall semester begins with the apotheosis of the European Enlightenment and the early phases of the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century. From there, it proceeds in a rough chronology through the “long” nineteenth century. Developments in Europe and North America are situated in relation to worldwide processes including trade, imperialism, nationalism, and industrialization. Sequentially, the course considers specific questions and problems that form around differences that are also connections, antitheses that are also interdependencies, and conflicts that are also alliances. The resulting tensions animated architectural discourse and practice throughout the period, and continue to shape our present. Each week, objects, ideas, and events will move in and out of the European and North American frame, with a strong emphasis on relational thinking and contextualization. This includes a historical, relational understanding of architecture itself. Although the Western tradition had recognized diverse building practices as “architecture” for some time, an understanding of architecture as an academic discipline and as a profession, which still prevails today, was only institutionalized in the European nineteenth century. -

2014 Neighborhood Profiles | WDCEP

MOUNT VERNON TRIANGLE Mount Vernon Triangle is one of downtown’s most active and convenient neighborhoods with an exciting variety of places to live, work, shop and dine. The neighborhood is positioned at an ideal 650 location in the East End of downtown within walking distance to the Convention Center, Gallery Employees at the Association of Place/Verizon Center and the U.S. Capitol. American Medical Colleges HQ opening in early 2014 The neighborhood is welcoming, authentic, and following. Leading restaurateurs have announced centered, mirroring DC’s unique mix of historic new headline locations in Mount Vernon Triangle and modern buildings, longtime and new residents, for 2014, including the latest offering from Al Dente and diverse cultures, restaurants, and experiences. restaurants, Alba Osteria, and George Vetsch’s new These qualities have resulted in more than $1.3 kitchen, Silo. $100,000+ billion private sector investment since 2004. With Average household income 3,000 existing residential units (and another 689 Mount Vernon Triangle is highly walkable and within a half-mile under construction), 1.7 million square feet of office accessible. The neighborhood has benefited from space, 200,000 square feet of retail space and 228 major streetscape investments that have created high hotel rooms, the 19-block Mount Vernon Triangle quality, well-landscaped and tree-lined streets with is considered to be one of DC’s best examples of an inviting outdoor seating. Public transit is available $484,000 emerging mixed-use community. Projected build-out at four Metrorail stations (Mount Vernon Square- includes a total of more than 4,500 residential units, Convention Center, Gallery Place-Chinatown, Average condo closing price three million square feet of office space, 336,000 Judiciary Square, and Union Station), with extensive 2 in the Mt. -

Delegated Action Template

Delegated Action of the Executive Director PROJECT NCPC FILE NUMBER Relocation of Historic Watchbox 7628 Washington Navy Yard Washington, DC NCPC MAP FILE NUMBER 41.11(61.10)44048 SUBMITTED BY ACTION TAKEN United States Department of the Navy Preliminary and final approval of site and building plans REVIEW AUTHORITY Approval per 40 U.S.C. § 8722(b)(1) and (d) The Navy has submitted preliminary and final site and building plans for the relocation of a historic watchbox from Naval Support Facility Indian Head, Maryland to the Washington Navy Yard. The project is mitigation for the adverse effect caused by the demolition of Piers 3 and 4 at the Washington Navy Yard. Piers 3 and 4 are contributing elements to the Washington Navy Yard Central Yard National Historic Landmark. As such, their demolition constitutes an adverse effect on historic properties. Under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, the Navy entered into a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with the District of Columbia State Historic Preservation Officer and Maryland Historical Trust to mitigate the adverse effect. The mitigation defined in the MOA was to relocate a historic watchbox from Naval Support Facility Indian Head, Maryland to the Washington Navy Yard. The watchbox was constructed ca. 1853-1854 at the Washington Navy Yard. It stood just inside the Latrobe Gate (8th and M Streets SE) and functioned as a sentry post manned by Marines assigned to the Washington Navy Yard. In approximately 1905, the building was moved to the Naval Proving Ground at Indian Head. The watchbox has been at three locations at Indian Head and has served as a foreman’s office, telephone switchboard office, and storage building. -

Capitol Hill Transportation Study: Final Report December 2006 Appendix C

APPENDIX C: TRANSPORTATION RECOMMENDATIONS BY INDEX NUMBER Capitol Hill Transportation Study: Final Report December 2006 Appendix C DISTRICT DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Capitol Hill Transportation Study Transportation Issues and Recommendations Map Issue Index Category Term Location Issue Source Comments from Field Visit Recommendation Install MUTCD compliant "Bike Route" signs; paint MUTCD-compliant bike lane 1 Bike Short 4th Street SE Bicycle lanes on 4th Street SE need bicycle symbol and lane arrows. FV Field Verified by on 18-19-2005 markings on street surface Speed limit sign for school zone on 6th Street NE between E Street and F Street Replace any existing "School Zone" signs with MUTCD-Compliant School Zone 2 Road & Inter Immediate 6th Street NE between E Street and F Street FV does not have a flashing beacon. signs with flashing beacons A meeting participant suggested that the existing traffic signal at the intersection Requires further evaluation through a field study. If traffic conditions warrant, 3 Road & Inter Maryland Avenue and 9th Street NE C of 9th Street and Maryland Avenue is not needed. existing signal can be replaced with an alternative form of control. Install ped signals with countdown timers at all crosswalks; install highly visible Lack of pedestrian signals, crosswalk and ADA compliant ramps at Maryland 4 Road & Inter Medium Maryland Avenue and 9th Street NE FV New ramp on west side, nothing on east side "Zebra Stripe" crosswalks at all crossings; ensure all crosswalks have ADA- Avenue and 9th Street NE. compliant ramps Requires further evaluation through a field study. If pavement and road subbase 5 Road & Inter 8th St. -

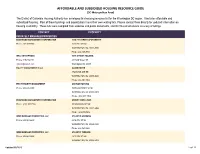

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central