Big Sur Doghole Ports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park

Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park Environmental Camping and Day-Use Area Big Sur, CA • (831) 667-2315 www.parks.ca.gov Located on Highway 1 at mile marker 36 you’ll find Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park. This state park is named after Julia Pfeiffer Burns, a well respected pioneer woman in the Big Sur country. The park stretches from the Big Sur coastline into nearby 3,000-foot ridges. It features redwood, tan oak, madrone, chaparral, and an 80-foot waterfall that drops from granite cliffs into the ocean from the Overlook Trail. A panoramic view of the ocean and miles of rugged coastline maybe seen from the higher elevations along the trails east of Highway 1. FEES for day use parking are due upon entry into Trespassing into the closed areas may result in the park. Fee envelopes for self registration are citation and ejection from the park. located at the self pay station near the restrooms. ROPES, lines, swings or hammocks may not be Fee amounts for day use are posted. fastened to any plant, fence or park structure. Attach CAMPING is extremely popular year round and is lines to your own property only. generally available only by advance reservation. BICYCLES are not allowed on any hiking trails Campers parking vehicles in the main parking within the park. lot should display proof of reservation in the windshield. Campers may also check in at the kiosk FIREARMS/WEAPONS OR HUNTING is not in Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park (12 miles north) to get allowed. Possession of loaded firearms and air rifles vehicle tags also valid for day use entrance into is prohibited. -

April 1999 SCREE

January, 2001 Peak Climbing Section, Loma Prieta Chapter, Sierra Club Vol. 35 No. 1 World Wide Web Address: http://www.sierraclub.org/chapters/lomaprieta/pcs Next General Meeting 2001 Publicity Committee Date: Tuesday, January 9 The PCS Publicity Committee for the year 2001 is the following: Time: 7:30 PM Mailings: Paul Vlasveld Listmaster: Steve Eckert Program: Annapurna III, Southwest Buttress Webmaster: Jim Curl In October 1978 a team of people including Ann Scree Editor: Bob Bynum Reynolds made their way to Annapurna III with the I will announce the various e-mail addresses and contact objective of climbing the southwest buttress. information once I get that straightened out. Avalanche conditions on the mountain forced them to We can also use more help with the printing and mailing. If you are interested, please contact me. rethink their route and a line up the west face was chosen. Join us for a slide show by Ann Reynolds • Rick Booth, PCS PubComm Chair recounting this journey. A $2 donation is requested for the slide show. Farewell As Webmaster Location Peninsula Conservation Center 3921 Back in 1994, when the world wide web was young, Silicon East Bayshore Rd, Palo Alto, CA Graphics CEO Ed McCracken instructed all employees that the Directions: From 101: Exit at San Antonio Road, web was our future. He arranged to provide an internet server on the SGI site to be used for employees personal sites and for Go East to the first traffic light, Turn community service pages. I jumped at the opportunity, and left and follow Bayshore Rd to the without stopping to obtain permission from the Sierra Club, I PCC on the corner of Corporation created the first PCS web site on the SGI server. -

Grooming Veterinary Pet Guidelines Doggie Dining

PET GUIDELINES GROOMING VETERINARY We welcome you and your furry companions to Ventana Big Sur! In an effort to ensure the peace and tranquility of all guests, we ask for your PET FOOD EXPRESS MONTEREY PENINSULA assistance with the following: 204 Mid Valley Shopping VETERINARY EMERGENCY & Carmel, CA SPECIALTY CENTER A non-refundable, $150 one-time fee per pet 831-622-9999 20 Lower Ragsdale Drive will be charged to your guestroom/suite. Do-it-yourself pet wash Suite 150 Monterey, CA Pets must be leashed at all times while on property. 831.373.7374 24 hours, weekends and holidays Pets are restricted from the following areas: Pool or pool areas The Sur House dining room Spa Alila Organic garden Owners must be present, or the pet removed from the room, for housekeeping to freshen your guestroom/suite. If necessary, owners will be required to interrupt activities to attend to a barking dog that may be disrupting other guests. Our concierge is happy to help you arrange pet sitting through a local vendor (see back page) if desired. These guidelines are per county health codes; the only exceptions are for certified guide dogs. DOGGIE DINING We want all of our guests to have unforgettable dining experiences at Ventana—so we created gourmet meals for our furry friends, too! Available 7 a.m. to 10 p.m through In Room Dining or at Sur House. Chicken & Rice $12 Organic Chicken Breast / Fresh Garden Vegetables / Basmati Rice Coco Patty $12 Naturally Raised Ground Beef / Potato / Garden Vegetables Salmon Bowl $14 Salmon / Basmati Rice / Sweet Potato -

Infrastructure Improvements IMPROVEMENTS INFORMATION Opportunities (1/2)

INFRASTRUCTURE TRAVELER Infrastructure Improvements IMPROVEMENTS INFORMATION Opportunities (1/2) Restroom Opportunities Addressing the limited number of public Recommendations to improve corridor restrooms could increase the confidence of experience for visitors and residents: transit and shuttle users that their needs met • Solutions require multi-agency and could address a critical need for the corridor. partnerships with land managers • Additional sites for restrooms (new restrooms are planned at Garrapata Advanced signage State Park, but others are likely needed) • Advanced signage and increased Visitor information traveler information (it is often not (pamphlets, phone app) clear that restrooms are available, especially at fee areas) Regular intervals • Multi-agency visitor hubs could throughout the corridor provide facilities and inform people of other facilities Slow Vehicle Turnout Opportunities Paved Viewpoint Opportunities Paving and signing turnouts can reassure Improvements to appropriate viewpoints motorists that they are able to more could organize parking and indicate easily pull over to let faster vehicles pass. desired movement patterns. Paved surfacing Paved viewpoint with delineated parking Potential frequency to plan for: approx. every 5 miles Boulders, berms, and vegetation delineate lookout areas Signage in advance of turnout Big Sur Highway 1 Sustainable Transportation Demand Management Plan Caltrans • Big Sur Corridor October 2019 INFRASTRUCTURE Infrastructure Improvements IMPROVEMENTS Opportunities (2/2) Technology Infrastructure Opportunities The use of mobile • Efforts to address the issue Carmel-by-the-Sea applications are underway. and ability to • Microcell technologies and other alternatives could be provide real-time Big Sur Posts updates for transit, considered. • A new tower is planned in Slates Hot shuttles, or parking Springs southern Big Sur Valley at Some parks without comprehensive cell coverage have availability is limited Lucia opted to designate cellular sites. -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

PT. SUR NAVAL FACILITY, PT. SUR, CA: a BRIEF HISTORY February 8, 2010

PT. SUR NAVAL FACILITY, PT. SUR, CA: A BRIEF HISTORY February 8, 2010 The Significance of the Point Sur Naval Facility. According to the dictionary, significance is “the quality of being important.” In the field of historic preservation the word has a special meaning. Assessing significance involves determining the importance of a historic resource, whether a building, site, or something else, within the broad sweep of history. To do this, the resource must be placed into a historic context. A historic context is a backdrop within which a historic resource can be viewed. One cannot look at a building in a vacuum, it must be looked at in the broader context within which it exists. From this historic context, the relative importance of a resource can be determined. Point Sur’s Role in the Winning of the Cold War. During the Cold War as the Soviet Union rapidly built-up its submarine force, U.S. antisubmarine warfare took on a growing significance. One critical American development was pioneering detection of low frequency submarine sound propagation in the sea. This led to development of the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), which were employed at Naval Facilities (NAVFACs) across the globe. SOSUS greatly assisted the U.S. in maintaining its dominance in anti-submarine warfare, and was critical to American efforts to win the Cold War. Established in 1957, the Pt. Sur NAVFAC is one of the few remaining complete Naval Facilities, and the only one remaining on the west coast. While other Naval Facilities were parts of larger military complexes, Pt. Sur was established as a stand-alone, self-sufficient base. -

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Description Job Number Date Thompson Lawn 1350 1946 August Peter Thatcher 1467 undated Villa Moderne, Taylor and Vial - Carmel 1645-1951 1948 Telephone Building 1843 1949 Abrego House 1866 undated Abrasive Tools - Bob Gilmore 2014, 2015 1950 Inn at Del Monte, J.C. Warnecke. Mark Thomas 2579 1955 Adachi Florists 2834 1957 Becks - interiors 2874 1961 Nicholas Ten Broek 2878 1961 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1517 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1581 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1873 circa 1945-1960 Portraits unnumbered circa 1945-1960 [Naval Radio Training School, Monterey] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 [Men in Hardhats - Sign reads, "Hitler Asked for It! Free Labor is Building the Reply"] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 CZ [Crown Zellerbach] Building - Sonoma 81510 1959 May C.Z. - SOM 81552 1959 September C.Z. - SOM 81561 1959 September Crown Zellerbach Bldg. 81680 1960 California and Chicago: landscapes and urban scenes unnumbered circa 1945-1960 Spain 85343 1957-1958 Fleurville, France 85344 1957 Berardi fountain & water clock, Rome 85347 1980 Conciliazione fountain, Rome 84154 1980 Ferraioli fountain, Rome 84158 1980 La Galea fountain, in Vatican, Rome 84160 1980 Leone de Vaticano fountain (RR station), Rome 84163 1980 Mascherone in Vaticano fountain, Rome 84167 1980 Pantheon fountain, Rome 84179 1980 1 UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Quatre Fountain, Rome 84186 1980 Torlonai -

3.1.1 Introduction This Section Describes the Aesthetic and Visual

Paraiso Springs Resort Draft Environmental Impact Report 3.1 Aesthetics and Visual Resources 3.1 AESTHETICS AND VISUAL RESOURCES 3.1.1 Introduction This section describes the aesthetic and visual resource conditions at the project site and in the project vicinity; presents the regulatory framework applicable to the proposed project; and discusses the potential aesthetic impacts that could result from implementation of the proposed project. The primary aesthetic concerns associated with the proposed project are potential changes in aesthetic character of the project site; impacts to public viewsheds; and/or obstruction of existing views. The project-specific information and analysis within this section is primarily based on project plans and site reconnaissance and photo documentation of the project site performed by RBF Consulting during the spring of 2007, and a subsequent site visit and documentation by EMC Planning Group in the fall of 2012. 3.1.2 Environmental Setting Local Visual Resources The project site consists of about 235 acres nestled in the mouth of a canyon extending westward into the foothills located at the western terminus of Paraiso Springs Road on the eastern slope of the Sierra de Salinas Foothills in the Salinas Valley, approximately seven miles west of the City of Greenfield. Elevations at the project site range from approximately 1,000 feet in the southern portion of the project site to slightly over 2,400 feet along the ridgelines. Views from the project site consist of scenic ridgelines north, west, and south, and the expansive Salinas Valley to the east. Surrounding land uses currently consist of agricultural uses and grazing, as well as several single-family residences located along Paraiso Springs Road located east of the project site. -

Must Road Trips

Must PHOTO COURTESY OF SEEMONTERY.COM OF COURTESY PHOTO Bixby Creek Bridge Monterey LoveRoad Trips Carmel-by-the-Sea Our writer’s romantic getaway gone Big Sur wrong leads to a revelation along Pfeiffer Beach California’s Highway 1. McWay Falls By Alan Rider Lucia Gorda Ragged Point McWay Falls in Monterey County is visible from COURTESY OF SEEMONTEREY.COM California’s Highway 1. San Simeon Cambria hey say that the road to true love is filled with in hand and weather forecasts promising sunny skies and pull over somewhere safe if you want to snap pics), and on ups and downs. Here’s proof that that’s no mere balmy temperatures, I had no choice but to go on one of to Andrew Molera State Park. There, I met up with the folks aphorism. the world’s most romantic road trips solo (sad face). from the Ventana Wildlife Society for a four-hour excursion TYou see, my most recent romantic interest—let’s call Pulling out of the parking lot of the oceanfront Sanctuary to locate endangered California condors in the wild. Using her Wendy because that’s her name—and I were brought Beach Resort in Monterey that first morning, I found running a radio-tracking antenna and a spotting scope, our guide together by our mutual love of road trips. Her online dating the Miata RF’s six-speed manual through the gears to be gave us a rare look at these gigantic birds that are slowly but profile made clear she was thoroughly into them, and I’m surprisingly therapeutic. -

Carmel Pine Cone, September 24, 2007

Folksinging Principal honored May I offer you legend plays for athletics, a damp shoe? Sunset Center academics — INSIDE THIS WEEK BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID CARMEL, CA Permit No. 149 Volume 93 No. 38 On the Internet: www.carmelpinecone.com September 21-27, 2007 Y OUR S OURCE F OR L OCAL N EWS, ARTS AND O PINION S INCE 1915 Pot bust, gunfire Ready for GPU may thwart at Garland Park her closeup ... Rancho Cañada By MARY BROWNFIELD housing project FIVE MEN suspected of a cultivating marijuana near Garland Park were arrested at gunpoint late By KELLY NIX Monday morning in the park’s parking lot following a night of strange occurrences that included gunfire, a THE AFFORDABLE housing “overlay” at the mouth of chase and hikers trying to flag down motorists at mid- Carmel Valley outlined in the newly revised county general night on Carmel Valley Road, according to Monterey plan could jeopardize the area’s most promising affordable County Sheriff’s Deputy Tim Krebs. housing development, its backers contend. The saga began Sunday afternoon, when a pair of The Rancho Cañada Village project, a vision of the late hikers saw two men with duffle bags and weapons walk Nick Lombardo, would provide 281 homes at the mouth of out of a nearby canyon. Afraid, one of the hikers yelled, Carmel Valley, constructed on land which is part of the “Police!” prompting the men to drop the bags and run, Rancho Cañada golf course. according to Krebs. According to the plan, half the homes would be sold at The duffles were full of freshly cut marijuana, market prices, subsidizing the which the hikers decided to take, according to the sher- other half, which would be iff’s department. -

Coastal Management Accomplishments in the Big Sur Coast Area

CCC Hearing Item: Th 13.3 February 9, 2012 _______________________________________________________________ California Coastal Commission’s 40th Anniversary Report Coastal Management in Big Sur History and Accomplishments Gorda NORTHERN BIG SUR Gorda NORTHERN BIG SUR CENTRAL BIG SUR Gorda NORTHERN BIG SUR CENTRAL BIG SUR SOUTHERN BIG SUR Gorda “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, southbound, north of Soberanes Point. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, at Cape San Martin, Big Sur Coast. CCRP#1649 9/2/2002 “A Highway Runs Through It” Heading south on Highway One. “A Highway Runs Through It” Southbound Highway One, near Partington Point. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, south of Mill Creek. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Historic Big Creek Bridge, at entrance to U.C. Big Creek Reserve. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, looking south to the coastal terrace at Pacific Valley. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, at Monterey County line, looking south into San Luis Obispo County, with Ragged Point and Piedras Blancas in far distance (on the right). ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 NORTHERN BIG SUR “Grand Entrance View” (from the north) of the Big Sur Coast, looking southwards to Soberanes Point, with Point Sur in the distance (on the horizon to the right). ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 Garrapata State Park/Beach, looking north to Soberanes Point. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 Mouth of Garrapata Creek (from Highway One). ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 Sign for Rocky Point Restaurant, with Notley’s Landing and Rocky Creek Bridge in distance. -

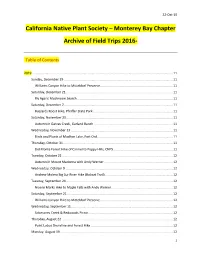

Monterey Bay Chapter Archive of Field Trips 2016

22-Oct-19 California Native Plant Society – Monterey Bay Chapter Archive of Field Trips 2016- Table of Contents 2019 ............................................................................................................................................................ 11 Sunday, December 29 ......................................................................................................................... 11 Williams Canyon Hike to Mitteldorf Preserve................................................................................. 11 Saturday, December 21....................................................................................................................... 11 Fly Agaric Mushroom Search .......................................................................................................... 11 Saturday, December 7......................................................................................................................... 11 Buzzards Roost Hike, Pfeiffer State Park ......................................................................................... 11 Saturday, November 23 ...................................................................................................................... 11 Autumn in Garzas Creek, Garland Ranch ........................................................................................ 11 Wednesday, November 13 ................................................................................................................. 11 Birds and Plants of Mudhen Lake, Fort