Assessing, Demonstrating and Capturing the Economic Value of Marine & Coastal Ecosystem Services in the Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electricity Needs Assessment

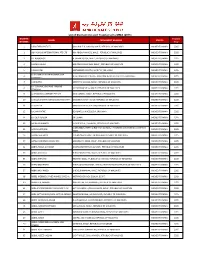

Electricity needs Assessment Atoll (after) Island boxes details Remarks Remarks Gen sets Gen Gen set 2 Gen electricity electricity June 2004) June Oil Storage Power House Availability of cable (before) cable Availability of damage details No. of damaged Distribution box distribution boxes No. of Distribution Gen set 1 capacity Gen Gen set 1 capacity Gen set 2 capacity Gen set 3 capacity Gen set 4 capacity Gen set 5 capacity Gen Gen set 2 capacity set 2 capacity Gen set 3 capacity Gen set 4 capacity Gen set 5 capacity Gen Total no. of houses Number of Gen sets Gen of Number electric cable (after) cable electric No. of Panel Boards Number of DamagedNumber Status of the electric the of Status Panel Board damage Degree of Damage to Degree of Damage to Degree of Damaged to Population (Register'd electricity to the island the to electricity island the to electricity Period of availability of Period of availability of HA Fillladhoo 921 141 R Kandholhudhoo 3,664 538 M Naalaafushi 465 77 M Kolhufushi 1,232 168 M Madifushi 204 39 M Muli 764 134 2 56 80 0001Temporary using 32 15 Temporary Full Full N/A Cables of street 24hrs 24hrs Around 20 feet of No High duty equipment cannot be used because 2 the board after using the lights were the wall have generators are working out of 4. reparing. damaged damaged (2000 been collapsed boxes after feet of 44 reparing. cables,1000 feet of 29 cables) Dh Gemendhoo 500 82 Dh Rinbudhoo 710 116 Th Vilufushi 1,882 227 Th Madifushi 1,017 177 L Mundoo 769 98 L Dhabidhoo 856 130 L Kalhaidhoo 680 94 Sh Maroshi 834 166 Sh Komandoo 1,611 306 N Maafaru 991 150 Lh NAIFARU 4,430 730 0 000007N/A 60 - N/A Full Full No No 24hrs 24hrs No No K Guraidhoo 1,450 262 K Huraa 708 156 AA Mathiveri 73 2 48KW 48KW 0002 48KW 48KW 00013 breaker, 2 ploes 27 2 some of the Full Full W/C 1797 Feet 24hrs 18hrs Colappes of the No Power house, building intact, only 80KW generator set of 63A was Distribution south east wall of working. -

Population and Housing Census 2014

MALDIVES POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’, Maldives 4 Population & Households: CENSUS 2014 © National Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Maldives - Population and Housing Census 2014 All rights of this work are reserved. No part may be printed or published without prior written permission from the publisher. Short excerpts from the publication may be reproduced for the purpose of research or review provided due acknowledgment is made. Published by: National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’ 20379 Republic of Maldives Tel: 334 9 200 / 33 9 473 / 334 9 474 Fax: 332 7 351 e-mail: [email protected] www.statisticsmaldives.gov.mv Cover and Layout design by: Aminath Mushfiqa Ibrahim Cover Photo Credits: UNFPA MALDIVES Printed by: National Bureau of Statistics Male’, Republic of Maldives National Bureau of Statistics 5 FOREWORD The Population and Housing Census of Maldives is the largest national statistical exercise and provide the most comprehensive source of information on population and households. Maldives has been conducting censuses since 1911 with the first modern census conducted in 1977. Censuses were conducted every five years since between 1985 and 2000. The 2005 census was delayed to 2006 due to tsunami of 2004, leaving a gap of 8 years between the last two censuses. The 2014 marks the 29th census conducted in the Maldives. Census provides a benchmark data for all demographic, economic and social statistics in the country to the smallest geographic level. Such information is vital for planning and evidence based decision-making. Census also provides a rich source of data for monitoring national and international development goals and initiatives. -

Table 2.3 : POPULATION by SEX and LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995

Table 2.3 : POPULATION BY SEX AND LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000 , 2006 AND 2014 1985 1990 1995 2000 2006 20144_/ Locality Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Republic 180,088 93,482 86,606 213,215 109,336 103,879 244,814 124,622 120,192 270,101 137,200 132,901 298,968 151,459 147,509 324,920 158,842 166,078 Male' 45,874 25,897 19,977 55,130 30,150 24,980 62,519 33,506 29,013 74,069 38,559 35,510 103,693 51,992 51,701 129,381 64,443 64,938 Atolls 134,214 67,585 66,629 158,085 79,186 78,899 182,295 91,116 91,179 196,032 98,641 97,391 195,275 99,467 95,808 195,539 94,399 101,140 North Thiladhunmathi (HA) 9,899 4,759 5,140 12,031 5,773 6,258 13,676 6,525 7,151 14,161 6,637 7,524 13,495 6,311 7,184 12,939 5,876 7,063 Thuraakunu 360 185 175 425 230 195 449 220 229 412 190 222 347 150 197 393 181 212 Uligamu 236 127 109 281 143 138 379 214 165 326 156 170 267 119 148 367 170 197 Berinmadhoo 103 52 51 108 45 63 146 84 62 124 55 69 0 0 0 - - - Hathifushi 141 73 68 176 89 87 199 100 99 150 74 76 101 53 48 - - - Mulhadhoo 205 107 98 250 134 116 303 151 152 264 112 152 172 84 88 220 102 118 Hoarafushi 1,650 814 836 1,995 984 1,011 2,098 1,005 1,093 2,221 1,044 1,177 2,204 1,051 1,153 1,726 814 912 Ihavandhoo 1,181 582 599 1,540 762 778 1,860 913 947 2,062 965 1,097 2,447 1,209 1,238 2,461 1,181 1,280 Kelaa 920 440 480 1,094 548 546 1,225 590 635 1,196 583 613 1,200 527 673 1,037 454 583 Vashafaru 365 186 179 410 181 229 477 205 272 -

Maldives Map 2012

MAP OF MALDIVES Thuraakunu Van ’gaa ru Uligamu Innafinolhu Madulu Thiladhunmathee Uthuruburi Berinmadhoo Gaamathikulhudhoo (Haa Alifu Atoll) Matheerah Hathifushi Govvaafushi Umarefinolhu Medhafushi Mulhadhoo Maafinolhu Velifinolhu Manafaru (The Beach House at Manafaru Maldives) Kudafinolhu Huvarafushi Un’gulifinolhu Huvahandhoo Kelaa Ihavandhoo Gallandhoo Beenaafushi Kan’daalifinolhu Dhigufaruhuraa Dhapparuhuraa Dhidhdhoo Vashafaru Naridhoo Filladhoo Maarandhoo Alidhuffarufinolhu Thakandhoo Gaafushi Alidhoo (Cinnamon Island Alidhoo) Utheemu Muraidhoo UPPER NORTH PROVINCE Mulidhoo Dhonakulhi Maarandhoofarufinolhu Maafahi Baarah Faridhoo Hon’daafushi Hon’daidhoo Veligan’du Ruffushi Hanimaadhoo Naivaadhoo Finey Theefaridhoo Hirimaradhoo Kudafarufasgandu Nellaidhoo Kanamana Hirinaidhoo Nolhivaranfaru Huraa Naagoashi Kurin’bee Muiri Nolhivaramu Kun’burudhoo Kudamuraidhoo Kulhudhuffushi Keylakunu Thiladhunmathee Dhekunuburi Kattalafushi Kumundhoo Vaikaradhoo (Haa Dhaalu Atoll) Vaikaramuraidhoo Neykurendhoo Maavaidhoo Kakaa eriyadhoo Gonaafarufinolhu Neyo Kan’ditheemu Kudadhoo Goidhoo Noomaraa Miladhunmadulu Uthuruburi (Shaviyani Atoll) Innafushi Makunudhoo Fenboahuraa Fushifaru Feydhoo Feevah Bileiyfahi Foakaidhoo Nalandhoo Dhipparufushi Madidhoo Madikuredhdhoo Gaakoshibi Milandhoo Narurin’budhoo Narudhoo Maakan’doodhoo Migoodhoo Maroshi Naainfarufinolhu Farukolhu Medhukun’burudhoo Hirubadhoo Dhonvelihuraa Lhaimagu Bis alhaahuraa Hurasfaruhuraa Funadhoo Naalaahuraa Kan’baalifaru Raggan’duhuraa Firun’baidhoo Eriadhoo Van’garu (Maakanaa) Boduhuraa -

List of Dormant Account Transferred to MMA (2015) GAZETTE Transfer NAME PERMANENT ADDRESS STATUS NUMBER Year

List of Dormant Account Transferred to MMA (2015) GAZETTE Transfer NAME PERMANENT ADDRESS STATUS NUMBER Year 1 3 BROTHERS PVT.LTD. GROUND FLR, G.NISSA, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 2 A&A ABACUS INTERNATIONAL PTE LTD MA.ABIDHA MANZIL, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 3 A.1.BOOKSHOP H.SHAAN LODGE, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 4 A.ARUMUGUM MAJEEDHIYA SCHOOL, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 5 A.BHARATHI SEETHEEMOLI SOCTH, MARIPAY, SRI LANKA MOVED TO MMA 2015 A.DH OMADHOO RAHKURIARUVAA 6 A.DH OMADHOO OFFICE, ADH.OMADHOO, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 COMMITEE 7 A.EDWARD AMINIYYA SCHOOL, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 A.F.CONTRACTING AND TRADING 8 V.FINIHIYAA VILLA, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 COMPANY 9 A.I.TRADING COMPANY PVT LTD M.VIHAFARU, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 10 A.INAZ/S.SHARYF/AISH.SADNA/M.SHARYF M.SUNNY COAST, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 11 A.J.DESILVA MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 12 A.K.JAYARATNE KOHUWELA, NUGEGODA, SRI LANKA MOVED TO MMA 2015 14 A.V.DE.P.PERERA SRI LANKA MOVED TO MMA 2015 19 AALAA MOHAMED SOSUN VILLA, L.MAAVAH, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 C/OSUSEELA,JYOTHI GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL, HANUMAN JUNCTION,W.G.DISTRICT, 25 AARON MARNENI MOVED TO MMA 2015 INDIA 26 AASISH WALSALM C/O MEYNA SCHOOL, LH.NAIFARU, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 27 AAYAA MOHAMED JAMSHEED MA.BEACH HOUSE, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 32 ABBAS ABDUL GAYOOM NOORAANEE FEHI, R.ALIFUSHI, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 33 ABBAS ABDULLA H.HOLHIKOSHEEGE, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 35 ABBAS IBRAHIM IRUMATHEEGE, AA.BODUFULHADHOO, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 36 ABBAS MOHAMED DHUBUGASDHOSHUGE, HDH.KULHUDHUFFSUHI, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 37 ABBAS MOHAMED DHEVELIKINAARAA, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 38 ABDEL MOEMEN SAYED AHMED SAYED A. -

Energy Supply and Demand

Technical Report Energy Supply and Demand Fund for Danish Consultancy Services Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources Maldives Project INT/99/R11 – 02 MDV 1180 April 2003 Submitted by: In co-operation with: GasCon Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report Map of Location Energy Consulting Network ApS * DTI * Tech-wise A/S * GasCon ApS Page 2 Date: 04-05-2004 File: C:\Documents and Settings\Morten Stobbe\Dokumenter\Energy Consulting Network\Løbende sager\1019-0303 Maldiverne, Renewable Energy\Rapporter\Hybrid system report\RE Maldives - Demand survey Report final.doc Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report List of Abbreviations Abbreviation Full Meaning CDM Clean Development Mechanism CEN European Standardisation Body CHP Combined Heat and Power CO2 Carbon Dioxide (one of the so-called “green house gases”) COP Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention of Climate Change DEA Danish Energy Authority DK Denmark ECN Energy Consulting Network elec Electricity EU European Union EUR Euro FCB Fluidised Bed Combustion GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green house gas (principally CO2) HFO Heavy Fuel Oil IPP Independent Power Producer JI Joint Implementation Mt Million ton Mtoe Million ton oil equivalents MCST Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology MOAA Ministry of Atoll Administration MFT Ministry of Finance and Treasury MPND Ministry of National Planning and Development NCM Nordic Council of Ministers NGO Non-governmental organization PIN Project Identification Note PPP Public Private Partnership PDD Project Development Document PSC Project Steering Committee QA Quality Assurance R&D Research and Development RES Renewable Energy Sources STO State Trade Organisation STELCO State Electric Company Ltd. -

Annual Report 2016.Pdf

#surpriseparty #familytime #healthyliving #philipsairfryer #stohomeimprovement Airfryer Rapid air technology enables you to fry, bake, roast & grill the tastiest meals with less fat than using little or no oil! Attention This report comprises the annual report of state trading organization plc prepared in accordance with the companies act of the republic of maldives (10/96), listing rules of maldives stock exchange, the securities act of the republic of maldives (2/2006), securities continuing disclosure obligations of issuers regulation 2010 of capital market development authority and corporate governance code of capital market development authority requirements. Unless otherwise stated in this annual report, the terms ‘STO’, the ‘group’, ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘our’ refer to state trading organization plc and its subsidiaries, associates and joint ventures collectively. The term ‘company’ refers to STO and/or its subsidiaries. STO prepares its financial statements in accordance with international financial reporting standards (IFRS). References to a year in this report are, unless otherwise indicated, references to the Company’s financial year ending 31st december 2016. In this report, financial and statistical information is, unless otherwise indicated, stated on the basis of the Company’s financial year. Information has been updated to the most practical date. This annual report contains forward looking statements that are based on current expectations or beliefs, as well as assumptions about future events. These forward looking statements can be identified by the fact that they do not relate only to historical or current facts. Forward looking statements often use words such as ‘anticipate’, ‘target’, ‘expect’, ‘estimate’, ‘intend’, ‘plan’, ‘goal’, ‘believe’, ‘will’, ‘may’, ‘should’, ‘would’, ‘could’ or other words of similar meaning. -

Rejected Applications

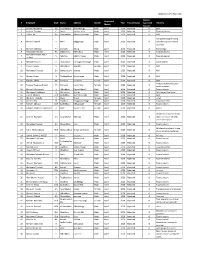

Updated on 24th May 2021 Payout Requested # Employee Atoll Island Address Gender Year Payout Status Approved Industry Month Amount 1 Fahud Mohamed Gn Fuvahmulah Vaseemeege Male April 2020 Rejected 0 N/A 2 Ibrahim Zameer F Feeali Noright Villa Male April 2020 Rejected 0 Tourism Sector 3 Thoha Ali Gn Fuvahmulah Dhoshimeynaage Male April 2020 Rejected 0 N/A Computer programming, 4 Ahmed Haneef K Male' Dhiggaruge Male April 2020 Rejected 0 consultancy and related activities 5 Ahmed Mahfooz TH Vilufushi Murig Male April 2020 Rejected 0 Technology 6 Fathuhulla Naseer HA Dhidhdhoo Hithadhoo Male April 2020 Rejected 0 Tourism Sector Mohamed Nahid Abdul 7 V Felidhoo Midhilimaage Male April 2020 Rejected 0 Tourism Sector Latheef 8 Mohamed Jaish S Hulhudhoo Jeymugasdhoshuge Male April 2020 Rejected 0 Construction 9 Shanaz Najmy S Hithadhoo Haavilla Female April 2020 Rejected 0 N/A 10 Mohamed Ayyoob GA Gemanafushi Yaadhu Male April 2020 Rejected 0 N/A 11 Ahmed Sham B Thulhaadhoo Rukumaage Male April 2020 Rejected 0 N/A 12 Aishath Shifza AA Feridhoo Suhaanee Female April 2020 Rejected 0 N/A Human health and social 13 Rugiyya Haamaa Ahmed TH Vilufushi Fabric Villa Female April 2020 Rejected 0 work activities 14 Ahmed Mushaaidh S Hithadhoo Flower Meed Male April 2020 Rejected 0 Tourist resort 15 Mohamed Nadheem S Maradhoo Startus Male April 2020 Rejected 0 Air transport services 16 Zuvaib Abdulla GDh Gadhdhoo Aasmaanu Villa Male April 2020 Rejected 0 N/A 17 Mariyam Abdulla K Male' Shaah Female April 2020 Rejected 0 other 18 Ahmed Riza Sh Feydhoo Nikagasdhoshuge -

The Shark Fisheries of the Maldives

The Shark Fisheries of the Maldives A review by R.C. Anderson and Hudha Ahmed Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, Republic of Maldives and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1993 Tuna fishing is the most important fisheries activity in the Maldives. Shark fishing is oneof the majorsecondary fishing activities. A large proportion of Maldivian fishermen fish for shark at least part-time, normally during seasons when the weather is calm and tuna scarce. Most shark products are exported, with export earnings in 1991 totalling MRf 12.1 million. There are three main shark fisheries. A deepwater vertical longline fishery for Gulper Shark (Kashi miyaru) which yields high-value oil for export. An offshore longline and handline fishery for oceanic shark, which yields fins andmeat for export. And an inshore gillnet, handline and longline fishery for reef and othe’r atoll-associated shark, which also yields fins and meat for export. The deepwater Gulper Shark stocks appear to be heavily fished, and would benefit from some control of fishing effort. The offshore oceanic shark fishery is small, compared to the size of the shark stocks, and could be expanded. The reef shark fisheries would probably run the risk of overfishing if expanded very much more. Reef shark fisheries are asource of conflict with the important tourism industry. ‘Shark- watching’ is a major activity among tourist divers. It is roughly estimated that shark- watching generates US $ 2.3 million per year in direct diving revenue. It is also roughly estimated that a Grey Reef Shark may be worth at least one hundred times more alive at a dive site than dead on a fishing boat. -

State of the Environment, Maldives 2001

Stateofthe Environment Report 2001 RepublicofMaldives MinistryofHomeAffairs,HousingandEnvironment CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 1 2 STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT .............................................................................................................. 3 2.1 GEOGRAPHY AND LAND......................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 MARINE AND COASTAL AREAS............................................................................................................. 8 2.3 CLIMATE................................................................................................................................................. 11 2.4 BIODIVERSITY........................................................................................................................................ 15 2.4.1 Terrestrial.................................................................................................................................... 15 2.4.2 Marine.......................................................................................................................................... 17 2.5 FRESHWATER......................................................................................................................................... 18 2.5.1 Groundwater.............................................................................................................................. -

Harbor Expansion Project FEEALI, FAAFU ATOLL

Maldive Transport and Contracting Company Pte Ltd Environmental Impact Assessment Report Harbor Expansion project FEEALI, FAAFU ATOLL January 2012 c Declaration of the Project Proponent and commitment letter Re: EIA report for proposed harbor expansion project at Faafu Feeali As the proponent of the proposed project We guarantee that We have read the report and to the best of Our knowledge all non-technical information provided here are accurate and complete. Also We hereby confirm Our commitment to finance and implement all mitigation measures and the monitoring program as specified in the report Signature: Name: Designation: Date: Declaration of the Consultant I certify that statements made in this Environment Impact Assessment Report Harbor Expansion project at Feeali, Faafu Atoll, to best of my knowledge are true, complete and correct. Name: Hussein Zahir Consultant Registration Number: 04-07 ` Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 a) Purpose of the Report and Need for the EIA ............................................................ 4 b) Structure of the Report ......................................................................................... 4 2. PROJECT SETTING ...................................................................................................... 6 a) Environment Protection and -

"Rights" Side of Life

THE “RIGHTS” SIDE OF LIFE - A BASELINE HUMAN RIGHTS SURVEY 1 2 THE “RIGHTS” SIDE OF LIFE - A BASELINE HUMAN RIGHTS SURVEY HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF THE MALDIVES THE “RIGHTS” SIDE OF LIFE - A BASELINE HUMAN RIGHTS SURVEY SURVEY REPORT This survey was sponsored by the United Nations Development Programme, Maldives and the report written by Peter Hosking, Senior Consultant, UNDP THE “RIGHTS” SIDE OF LIFE - A BASELINE HUMAN RIGHTS SURVEY 3 Foreword This is the first general human rights survey undertaken in the Maldives. The information it contains about Maldivians’ awareness of the Human Rights Commission, and their knowledge about and attitudes towards human rights will form the Commission’s priorities in the years ahead. The events of September 2003 (riots in the prison and the streets of Male’) led to the announcement by the President, on June 9, 2004, of a programme of democratic reforms. Along with the establishment of the HRCM were proposals to create an independent judiciary and an independent Parliament. Once in place, these reforms will herald a new era for the Maldives, where human rights are respected by the authorities and enjoyed by all. To date, only limited progress has been made with the reform programme. Even in relation to the Commission, although it was established on Human Rights Day, 10 December 2003, by decree, there have been delays in passing its founding law. Then there were deficiencies in the law when it was passed and amendments are required. There has also been a delay in the appointment of the Commission’s members. While this situation is greatly inhibiting the Commission’s ability to function at full capacity, some activities have been possible, including the undertaking of this baseline survey with the generous assistance of UNDP.