Academic Painting but Let’S Talk First About What It Was and How It Began

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

Tate Report 08-09

Tate Report 08–09 Report Tate Tate Report 08–09 It is the Itexceptional is the exceptional generosity generosity and and If you wouldIf you like would to find like toout find more out about more about PublishedPublished 2009 by 2009 by vision ofvision individuals, of individuals, corporations, corporations, how youhow can youbecome can becomeinvolved involved and help and help order of orderthe Tate of the Trustees Tate Trustees by Tate by Tate numerousnumerous private foundationsprivate foundations support supportTate, please Tate, contact please contactus at: us at: Publishing,Publishing, a division a divisionof Tate Enterprisesof Tate Enterprises and public-sectorand public-sector bodies that bodies has that has Ltd, Millbank,Ltd, Millbank, London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG helped Tatehelped to becomeTate to becomewhat it iswhat it is DevelopmentDevelopment Office Office www.tate.org.uk/publishingwww.tate.org.uk/publishing today andtoday enabled and enabled us to: us to: Tate Tate MillbankMillbank © Tate 2009© Tate 2009 Offer innovative,Offer innovative, landmark landmark exhibitions exhibitions London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG ISBN 978ISBN 1 85437 978 1916 85437 0 916 0 and Collectionand Collection displays displays Tel 020 7887Tel 020 4900 7887 4900 A catalogue record for this book is Fax 020 Fax7887 020 8738 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. DevelopDevelop imaginative imaginative education education and and available from the British Library. interpretationinterpretation programmes programmes AmericanAmerican Patrons Patronsof Tate of Tate Every effortEvery has effort been has made been to made locate to the locate the 520 West520 27 West Street 27 Unit Street 404 Unit 404 copyrightcopyright owners ownersof images of includedimages included in in StrengthenStrengthen and extend and theextend range the of range our of our New York,New NY York, 10001 NY 10001 this reportthis and report to meet and totheir meet requirements. -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

Secondary and FE Teacher Resource for Teaching Key Stages 3–5 Sculpture in the RA Collection a Sculpture Student at Work in the RA Schools in 1953

Secondary and FE Teacher Resource For teaching key stages 3–5 Sculpture in the RA Collection A sculpture student at work in the RA Schools in 1953. © Estate of Russell Westwood Contents Introduction Illustrated key works with information, quotes, key words, questions, useful links and art activities for the classroom Glossary Further reading To book your visit Email studentgroups@ royalacademy.org.uk or call 020 7300 5995 roy.ac/teachers ‘...we live in a world where images are in abundance and they’re moving, [...] they’re doing all kinds of things, very speedily. Whereas sculpture needs to be given time, you need to just wait with it and become the moving object that it isn’t, so this action between the still and the moving is incredibly demanding for all. ’ Phyllida Barlow RA The Council of the Royal Academy selecting Pictures for the Exhibition, 1875, Russel Cope RA (1876). Photo: John Hammond Introduction What is the Royal Academy of Arts? The Royal Academy (RA) was Every newly elected Royal set up in 1768 and 2018 was Academician donates a work of art, its 250th anniversary. A group of known as a ‘Diploma Work’, to the artists and architects called Royal RA Collection and in return receives Academicians (or RAs) are in charge a Diploma signed by the Queen. The of governing the Academy. artist is now an Academician, an important new voice for the future of There are a maximum of 80 RAs the Academy. at any one time, and spaces for new Members only come up when In 1769, the RA Schools was an existing RA becomes a Senior founded as a school of fine art. -

Mary and George Watts, Can Be Viewed As A

The following extract has kindly been provided by Dr Lucy Ella Rose, from her published work Suffragists Artists in Partnership. Edinburgh University Press (2018), Chapter 1 - Mary and George Watts. We are grateful to Lucy for allowing this to be used as part of ‘The March of the Women’ project resource. Practice and Partnership Much has been written about the famous Victorian artist George Watts, and yet the life and work of Mary Watts, and the couple’s progressive socio-political positions as conjugal creative partners and women’s rights supporters, are comparatively neglected. Long-eclipsed by the dominant critical focus on her husband, and known primarily as the worshipping wife of a world-famous artist, Mary was a pioneering professional woman designer and ceramicist as well as a painter, illustrator and writer. Despite her prominence in her own lifetime, she is little-known today. The lack of critical and biographical material on her is disproportionate to the originality, high quality and multi-faceted nature of her oeuvre, encompassing fine art, gesso relief, sculpture, ceramic and textile design, and architecture. Art historian Mark Bills’s chapter on the Wattses in An Artists’ Village: G. F. Watts and Mary Watts at Compton (Bills 2011: 9–23) incorporates the brief sections ‘Married Life’ and ‘A Partnership’, and yet they perpetuate rather than challenge traditional views of the couple. The former section presents Mary ‘in awe of [George], overwhelmed by his reputation […] as devoted and admiring as ever […] in her subservient role’ (2011: 14–15). Bills alludes to, without contesting, the popular public perception of Mary as George’s ‘nurse’ and ‘slave’ who ‘worshipped him blindly’ (2011: 15-16). -

The Kensington District

The Kensington District By G. E. Mitton The Kensington District When people speak of Kensington they generally mean a very small area lying north and south of the High Street; to this some might add South Kensington, the district bordering on the Cromwell and Brompton Roads, and possibly a few would remember to mention West Kensington as a far- away place, where there is an entrance to the Earl's Court Exhibition. But Kensington as a borough is both more and less than the above. It does not include all West Kensington, nor even the whole of Kensington Gardens, but it stretches up to Kensal Green on the north, taking in the cemetery, which is its extreme northerly limit. If we draw a somewhat wavering line from the west side of the cemetery, leaving outside the Roman Catholic cemetery, and continue from here to Uxbridge Road Station, thence to Addison Road Station, and thence again through West Brompton to Chelsea Station, we shall have traced roughly the western boundary of the borough. It covers an immense area, and it begins and ends in a cemetery, for at the south-western corner is the West London, locally known as the Brompton, Cemetery. In shape the borough is strikingly like a man's leg and foot in a top-boot. The western line already traced is the back of the leg, the Brompton Cemetery is the heel, the sole extends from here up Fulham Road and Walton Street, and ends at Hooper's Court, west of Sloane Street. This, it is true, makes a very much more pointed toe than is usual in a man's boot, for the line turns back immediately down the Brompton Road. -

Chasing Eliza: Shifting and Static Women in Elizabeth Craven's the Miniature Picture

ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640-1830 Volume 6 Issue 1 Volume 6.1 (Spring 2016) Article 2 2016 Chasing Eliza: Shifting and Static Women in Elizabeth Craven's The Miniature Picture Heather A. Ladd University of Lethbridge, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/abo Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ladd, Heather A. (2016) "Chasing Eliza: Shifting and Static Women in Elizabeth Craven's The Miniature Picture," ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640-1830: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. https://www.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/2157-7129.6.1.2 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/abo/vol6/iss1/2 This Scholarship is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640-1830 by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chasing Eliza: Shifting and Static Women in Elizabeth Craven's The Miniature Picture Abstract Georgian actress and author Mary Robinson famously wore a miniature portrait of her royal lover, the Prince of Wales, whom she captivated in the Shakespearean breaches role of Perdita. Intriguingly, Robinson’s final stage appearance was as the cross-dressing heroine of The Miniature Picture (1781), a three-act comedy penned by writer and socialite Lady Elizabeth Craven, later Baroness Craven and Margravine of Brandenburg-Ansbach. -

John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and the Promotion of a National Aesthetic

JOHN BOYDELL'S SHAKESPEARE GALLERY AND THE PROMOTION OF A NATIONAL AESTHETIC ROSEMARIE DIAS TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2003 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Volume I Abstract 3 List of Illustrations 4 Introduction 11 I Creating a Space for English Art 30 II Reynolds, Boydell and Northcote: Negotiating the Ideology 85 of the English Aesthetic. III "The Shakespeare of the Canvas": Fuseli and the 154 Construction of English Artistic Genius IV "Another Hogarth is Known": Robert Smirke's Seven Ages 203 of Man and the Construction of the English School V Pall Mall and Beyond: The Reception and Consumption of 244 Boydell's Shakespeare after 1793 290 Conclusion Bibliography 293 Volume II Illustrations 3 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a new analysis of John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery, an exhibition venture operating in London between 1789 and 1805. It explores a number of trajectories embarked upon by Boydell and his artists in their collective attempt to promote an English aesthetic. It broadly argues that the Shakespeare Gallery offered an antidote to a variety of perceived problems which had emerged at the Royal Academy over the previous twenty years, defining itself against Academic theory and practice. Identifying and examining the cluster of spatial, ideological and aesthetic concerns which characterised the Shakespeare Gallery, my research suggests that the Gallery promoted a vision for a national art form which corresponded to contemporary senses of English cultural and political identity, and takes issue with current art-historical perceptions about the 'failure' of Boydell's scheme. The introduction maps out some of the existing scholarship in this area and exposes the gaps which art historians have previously left in our understanding of the Shakespeare Gallery. -

Journal of the Short Story in English, 50 | Spring 2008 “In the Circle of the Lens”: Woolf’S “Telescope” Story, Scene-Making and Memory 2

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 50 | Spring 2008 Special issue: Virginia Woolf “In the Circle of the Lens”: Woolf’s “Telescope” Story, Scene-making and Memory Laura Marcus Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/702 ISSN : 1969-6108 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Rennes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 juin 2008 ISSN : 0294-04442 Référence électronique Laura Marcus, « “In the Circle of the Lens”: Woolf’s “Telescope” Story, Scene-making and Memory », Journal of the Short Story in English [En ligne], 50 | Spring 2008, mis en ligne le 01 juin 2011, consulté le 10 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/702 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 10 décembre 2020. © All rights reserved “In the Circle of the Lens”: Woolf’s “Telescope” Story, Scene-making and Memory 1 “In the Circle of the Lens”: Woolf’s “Telescope” Story, Scene-making and Memory Laura Marcus 1 Virginia Woolf noted in her diary for 31st January 1939: “I wrote the old Henry Taylor telescope story that has been humming in my head these 10 years” (Woolf 1984: 204). The short story to which she was referring was published as “The Searchlight”, in the posthumous A Haunted House and Other Stories.The “humming” had, however, already been transferred to the page ten years previously, when Woolf wrote a story which she entitled “What the Telescope Discovered”, followed a year later by the incomplete “Incongruous/Inaccurate Memories”. In all, Woolf produced some fourteen different drafts of “the telescope story”, with fragments of other drafts. -

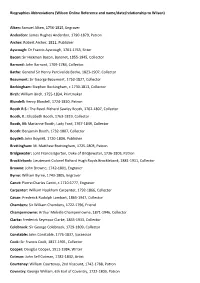

Biographies Abbreviations (Wilson Online Reference and Name/Date/Relationship to Wilson)

Biographies Abbreviations (Wilson Online Reference and name/date/relationship to Wilson) Alken: Samuel Alken, 1756-1815, Engraver Anderdon: James Hughes Anderdon, 1790-1879, Patron Archer: Robert Archer, 1811, Publisher Ayscough: Dr Francis Ayscough, 1701-1763, Sitter Bacon: Sir Hickman Bacon, Baronet, 1855-1945, Collector Barnard: John Barnard, 1709-1784, Collector. Bathe: General Sir Henry Percival de Bathe, 1823-1907, Collector Beaumont: Sir George Beaumont, 1753-1827, Collector Beckingham: Stephen Beckingham, c.1730-1813, Collector Birch: William Birch, 1755-1834, Printmaker Blundell: Henry Blundell, 1724-1810, Patron Booth R.S.: The Revd. Richard Sawley Booth, 1762-1807, Collector Booth, E.: Elizabeth Booth, 1763-1819, Collector Booth, M: Marianne Booth, Lady Ford, 1767-1849, Collector Booth: Benjamin Booth, 1732-1807, Collector Boydell: John Boydell, 1720-1804, Publisher Brettingham: M. Matthew Brettingham, 1725-1803, Patron Bridgewater: Lord Francis Egerton, Duke of Bridgewater, 1736-1803, Patron Brocklebank: Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hugh Royds Brocklebank, 1881-1911, Collector Browne: John Browne, 1742-1801, Engraver Byrne: William Byrne, 1743-1805, Engraver Canot: Pierre-Charles Canot, c.1710-1777, Engraver Carpenter: William Hookham Carpenter, 1792-1866, Collector Cavan: Frederick Rudolph Lambart, 1865-1947, Collector Chambers: Sir William Chambers, 1722-1796, Friend Champernowne: Arthur Melville Champernowne, 1871-1946, Collector Clarke: Frederick Seymour Clarke, 1855-1933, Collector Colebrook: Sir George Colebrook, 1729-1809, Collector Constable: John Constable, 1776-1837, Successor Cook: Sir Francis Cook, 1817-1901, Collector Cooper: Douglas Cooper, 1911-1984, Writer Cotman: John Sell Cotman, 1782-1842, Artist Courtenay: William Courtenay, 2nd Viscount, 1742-1788, Patron Coventry: George William, 6th Earl of Coventry, 1722-1809, Patron Dartmouth: William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, 1731-1801, Patron Daulby: Daniel Daulby, d. -

Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-18742-8 - Italian Culture in Northern Europe in the Eighteenth Century Edited by Shearer West Index More information INDEX (Illustrations are signalled by bold type) Aberdeen 130 frescos in Ottobeuren Abbey 27, 28, 29, 30 Abildgaard, Nicolai 205–6 Horatio Walpole and his Family 42–4, 44 Wounded Philoctetes 206 Musical Portrait Group: The Singer Farinelli and Friends academic art 70 38–44, 39 Acade´mie royale de musique et de danse, Paris 175, 181 Portrait of a Musician 30 Acade´mie royale de peinture et sculpture, Paris 59, 62, Queen Caroline 34, 36 119 Shakespeare and the Muses, fresco for Covent Garden academies 17 Theatre 23 Accademia degli Arcadi, Rome 150 staircase at Lord Tankerville’s house, St James’s Square, Accademia di San Luca, Rome 62, 76, 92n, 119 London 23 Accademia di Santa Clementina, Bologna 62 Viktoriensaal, Elector’s suite and Princess Apartments, Accerbi, Giuseppe 197 Schleissheim 22 Adam, James 121 ancien re´gime 15, 46, 196 Adam, Robert 96n, 121, 131 Andria 24 Addison, Joseph 101 ‘Angelica e Medoro’ 24 afterpiece 180 Anjou, duc d’ (later Philip V) 191 Agrigento 194, 204 Ankarstro¨m, Captain Jacob Johan 204 Aikema, Bernard 105 Ansbach 163 Alard, Charles 173 antique 76, 96, 107, 195, 201 Albani, Cardinal Alessandro 98, 194, 206 antiquities 87, 95 Alberoni, Abbe Giulio 9 antiquity 89, 91, 95, 151 Alberti, Conte Matteo 10 Antwerp 75 Alborghetti, Pietro 175 Apelles 62n, 100 Alembert, Jean Le Rond d’ 182 Venus Marina 100 Alexander VII, Pope 188 Apollo Belvedere 100, 194 Algarotti, Francesco -

Roman Art World in the 18Th Century (Rome, 10-11 Dec 18)

Roman Art World in the 18th Century (Rome, 10-11 Dec 18) British School at Rome - Accademia Nazional di San Luca, Rome, Dec 10–11, 2018 Registration deadline: Dec 11, 2018 Adriano Aymonino The Roman Art World in the 18th Century and the Birth of the Art Academy in Britain Conference: British School at Rome, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca in collaboration with the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Introduces Paolo Portoghesi (Accademia Nazionale di San Luca) This two-day conference focuses on the role of the Roman pedagogical model in the formation of British art and institutions in the long 18th century. Even as Paris progressively dominated the modern art world during the 18th century, Rome retained its status as the ‘academy’ of Europe, attracting a vibrant international community of artists and architects. Their exposure to the Antique and the Renaissance masters was supported by a complex pedagogical system. The network of the Accademia di San Luca, the Académie de France à Rome, the Capitoline Accademia del Nudo, the Concorsi Clementini, and numerous stu- dios and offices, provided a complete theoretical and educational model for a British art world still striving to create its own modern system for the arts. Reverberations from the Roman academy were felt back in Britain through a series of initiatives culminating in the foundation of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1768, which officially sanctioned and affirmed the Roman model. This conference addresses the process of intellectual migration, adaptation and reinterpretation of academic, theoretical and pedagogical principles from Rome to 18th-century Britain.