Journal 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zuid-Noorwegens Mooiste Dagwandelingen

ZUID-NOORWEGENS MOOISTE DAGWANDELINGEN Åmotan * ANWB 8 Leirungsdalen Aurlandsdalen 1 * ANWB 27 Liomseter Aurlandsdalen 2 * ANWB 28 Lom ANWB 21 Austerdalsbreen * ANWB 18 Måbødalen * ANWB 31 Bergen * (stad) ANWB 29 Månafossen Rother 46 Berger (dorpje) Molden * Besseggen * ANWB 22 Mølmannsdalen Bødalen * Ormtjernkampen * Rother 17 Bukkelægret ANWB 23 Preikestolen * Rother 44 Elgå Ringebufjellet ANWB 2 Erdalen Roholtfjellet * Finse ANWB 33 Romsdalen * Flåmsdalen * Rother 31 Runde * Fokstumyra * Skjenegge * Galdhøpiggen * Skomakarnibbå Gaustatoppen * Rother 9 Spåtind ANWB 25 Geiranger Storfjellet * Glitra * Storlidalen * Glomsdalen Straumbu Gutulia * Svellnosbreen * Hemsedal ANWB 35 Tovdal * Husedalen * Rother 36 Trollveggen * ANWB 11 Jonsknuten Utladalen * ANWB 24 Kjerag * Rother 45 Vassfaret * Kongsvoll * Viglesdalen * Lærdalen Vingelen • ANWB 8 = ANWB Wandelgids: Noorwegen, route 8 Rother 9 = Rother Wanderführer: Norwegen - Süd, Tour 9 • De 32 wandelingen met een * zijn de "allermooiste" pareltjes. .. Alleen deze 32 worden hier in de PDF gekopieerd. ÅMOTAN * • 3.30 uur. • Middelzware wandeling. • ANWB Wandelgids: Noorwegen, route 8. • Grote kloof aan de noordrand van de Dovrefjell. • Een rondwandeling bij Åmotan. .. Zo heet de imponerende kloof waar een aantal bergbeken bij elkaar komen. .. Er zijn daar ook drie watervallen: .. - Linndalsfallet (groot) in de Linndøla-rivier, .. - Reppfallet in de Reppa-rivier, .. - Svøufallet (groot) in de Grødøla-rivier. .. (In het kaartje hieronder staan alleen de twee grote ingetekend). • Je maakt ook een 'afsteker' (extra uitstapje) naar de oude bergboerderij .. Gammelsetra. • De eerste kilometer (tot aan de brug over de Linndøla) stijgt de route flink. .. Hetzelfde geldt voor de laatste 500 m als je uit de kloof omhoog klimt. .. De rest van de wandeling is gemakkelijk. • Die eerste kilometer kun je gedeeltelijk over bospaadjes langs de bovenrand van . -

Jotunheimen National Park

Jotunheimen National Park Photo: Øivind Haug Map and information Jotunheimen Welcome to the National Park National Parks in Norway Welcome to Jotunheimen An alpine landscape of high mountains, snow and glaciers whichever way you turn. This is how it feels to be on top of Galdhøpiggen: You know that at this moment in time you are at the highest point in Norway with firm ground under your feet. What you see around you are the highest mountains of Northern Europe. An alpine landscape of high mountains, deciduous forests and high waterfalls. snow and glaciers whichever way you The public footpath that winds its way turn. This is how it feels to be on top up the valley crosses over the wildly of Galdhøpiggen: You know that at this cascading Utla river many times on its moment in time you are at the highest way down the valley. point in Norway with firm ground under your feet. What you see around Can you see yourself on top of one you are the highest mountains of of the sharpest ridges? Mountain Northern Europe. climbing in Jotunheimen is as popular today as when the English started to Jotunheimen covers an area from explore these mountains during the the west country landscape of high, 1800s and many are still following sharp ridged peaks in Hurrungane, the in the footsteps of Slingsby and the most distinctive peaks, to the eastern other pioneers. country landscape of large valleys and mountain lakes. Do you dream about the jerk of the fishing rod when a trout bites? Do you The emerald green Gjende is the dream of escaping to the mountains in queen of the lakes. -

Dispensasjon - Bruk Av Drone for Filming Av Besseggen - NRK Hedmark Og Oppland

Postadresse Besøksadresse Kontakt Postboks 987 Norsk fjellsenter Sentralbord: +47 61 26 60 00 2604 LILLEHAMMER Brubakken 2, 2686 Lom Direkte: +47 948 80 564 Luster kommune, [email protected] Kommunehuset, 6868 Gaupne http://www.nasjonalparkstyre.no/jotunheimen NRK Hedmark og Oppland Saksbehandlar Kari Sveen Vår ref. 2017/3035-3 432.3 Dykkar ref. Dato 16.05.2017 Jotunheimen nasjonalpark - Dispensasjon - Bruk av drone for filming av Besseggen - NRK Hedmark og Oppland Viser til søknad av 03.05.17 og tilleggsopplysningar i e-post av 04.05.17. Nasjonalparkstyret behandla saka i møte 15. mai og gjorde slik vedtak: Med heimel i § 4 i verneforskrift for Jotunheimen nasjonalpark og naturmangfaldlovas § 48, jf. § 77, gjev Nasjonalparkstyret for Jotunheimen og Utladalen dispensasjon for bruk av drone for filmopptak for ei sending som viser turen over Besseggen minutt for minutt, i tråd med søknad av 03.05./04.05.17 frå NRK Hedmark og Oppland. Dispensasjonen gjeld for ein dag i løpet av august/september 2017 på følgjande vilkår: 1. Området er avgrensa til Gjende og ruta over Besseggen 2. Flyging nær dyr og hekkeplasser skal unngås. Det skal haldast avstand til eventuelle turfolk som er i området og flyging skal av omsyn til friluftslivet skje på vekedagar og ikkje i helger*. Aktuelle dagar er 25., 26. eller 27. august, eller ein av dagane 1., 2. eller 3. september 2017. 3. Filmen skal ikkje vise tekniske hjelpemiddel som drone, men berre vise sjølve turen. 4. SNO v/ Rigmor Solem skal ha melding om dato seinast dagen før kvar flyging via e-post ([email protected]) eller melding til mobilnummer 959 65 158. -

Norway - Fjords and Mountains a Once in a Lifetime Destination That Will Take You to Mountains, Glaciers, Deep Coastal Fjords and the Land of the Vikings and Trolls

Norway - Fjords and Mountains A once in a lifetime destination that will take you to mountains, glaciers, deep coastal fjords and the land of the Vikings and trolls... Trip Length: 21 days / 20 nights July - August 2023 Minimum 8 guests / Maximum 12 guests *8-9 guests NOK 70559 ($ 11300) 10-11 guests NOK 63500 ($ 10200) 12 guests NOK 58500 ($ 9400) *(AUD prices quoted based on exchange rate 2020. 2023 prices to be confirmed) Included meals marked each day. B = Breakfast, L = Lunch, D = Dinner Norwegians can’t get enough of nature and we’ve discovered why! Norway’s scenic landscapes are best discovered by following a path on foot. Late summer is the best time to experience a sunlit landscape that has forced the snow to retreat to the mountains and has woken the flowers to their full bloom. Long days, mild temperatures and the fabled midnight sun promise ideal walking conditions, and we will be surrounded with those vibrant natural colours of the changing landscape. We’ll discover untamed, mythical landscapes as we trapse the classic (and sometimes challenging) hiking trails of Preikestolen, Galdhøpiggen, and Besseggen Ridge. You’ll never forget your first approach aboard the Hurtigruten Ferry, to the unsurpassed beauty of the Lofoten Islands. Tall, craggy spires dominate the skyline and beckon walkers to their valleys and summits. We stay in hotels and mountain refuges, so there’s no camping on this trip. Norway - it’s a love affair with nature! Day 1: Monday Arrive Stavanger Airport (Sola) Arrive in Stavanger and make your way to our hotel in downtown Stavanger. -

ESHEP 2016 Excursion Heidi Sandaker Full Day Excursion - Jotunheimen Mountains

ESHEP 2016 Excursion Heidi Sandaker Full day excursion - Jotunheimen Mountains Departure(from(the(hotel:(08h00( !"!We!will!take!packed!lunches.!Each!person!is!asked!to!prepare!their!own!picnic!from!the!! !!!!breakfast!buffet;!carrier!bags!and!bo<les!of!water!will!be!provided! !"!Bring!plenty!of!water,!especially!if!you!are!doing!the!long!hike! !"!Bring!warm/rainproof!clothes,!and!hiking!shoes!if!you!have!them.!Suitable!footwear!is!essenCal!! !!!for!the!long!hike.! !"!Expect!some!mud!if!it!rains.! Arrival(at(Gjendesheim(:(10h00( !"!OpCon!A!:!Boat!trip,!then!long!hike!back!over!Besseggen!mountain! !"!OpCon!B!:!Boat!trip,!then!shorter!hike!back!near!the!lake!shore! !"!OpCon!C!:!Boat!trip!back!and!forth!along!the!lake! !"!OpCon!D!:!Stay!around!Gjendesheim!(possibility!of!a!short!hike,!or!just!relax!and!enjoy!the!view)!!! Departure(of(boats(for(op;on(A,(B,(C(:(10h00(and(10h15( Dinner(at(Gjendesheim(at(19h00.( !"!Three!courses!with!coffee/tea!! Buses(will(leave(Gjendesheim(at(20h30,(return(at(the(hotel(es;mated(to(22:30( Full day excursion - Jotunheimen Mountains Weather'forecast' A Full$day$excursion$on$June$21$–$Hiking$op8ons$ 20!min!boat(trip(to!Memurubu,!! • ~!7F8(h(hike(back!to!Gjendesheim!over(the(mountain(accompanied!by!a!mountain!guide.! • In!places!the!path!will!be!steep:!Not!suitable!for!people!who!suffer!from!verCgo! • A!reasonable!level!of!physical!fitness!necessary! • Suitable!footwear!!is!essenCal! • About!~13!km!distance! • 1100!m!of!elevaCon!gain!in!total! Moderate(difficulty(for(people(used(to(mountain(hiking.( http://www.roughguides.com/article/hiking-the- -

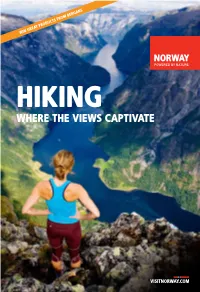

Where the Views Captivate Buh

WIN GREAT PRODUCTS FROM BERGANS HIKING WHERE THE VIEWS CAPTIVATE SVALBARD Sjuøyane Nordkapp Norden- Kvitøya skiøld- bukta Storøya ORVIN LAND GUSTAV V n e W LAND d r i j d Nordaustlandet NORWAY o j ef H j o i oodf n ALBERT I r l GUSTAV W d o LAND en p ADOLF HAAKON ANDRÈE e t Gamvik B n LAND te VII re North Cape n LAND t s LAND NY en 1368 S s e A 1454 FRIESLAND t rik Hurtigruten re Kapp E ik d Eidsvollfjellet te Er ngsfjorde t Mohn Abeløya 34 n r R Ko 1717 Berlevåg Ny Ålesund KONG KARLS Honningsvåg Kirkenes o Hiking regions: 1225 Newtontoppen Wilhelmøya Ri LAND 1085 val Kongsøya Kjøllefjord j E Fo Tre Kroner en OLAV V LAND su f r 1068 n Båtsfjord l d an e t Havøysund a PRINS OSCAR II Backlundtoppen Svenskøya n Varanger- Vardø N d LAND Kåfjord n KARLS s O un Spitsbergen e FORLAND lg a n a halvøya d e Barentsøya Porsanger- T s T e ord SABINE tr g t fj e Is te Varangerhalvøya t SOUTHERN NORWAY Page 6-11 Grumantbyen Longyearbyen halvøya n LAND 665 33 Nasjonalpark S Barentsburg Ifjord Kapp Linné Haastberget a Sveagruva NORDENSKJØLD 1 Setesdal Hammerfest s LAND Vadsø r S Edgeøya det NATHORST r d e n lsun n V a r a nge r f j o 2 Grenland el LAND o B e aSørøy Tana bru Grense WEDEL d E P JARLSBERG r rden Skaidi Jakobselv TORELL o jo 3 Middle-Telemark LAND j f v LAND f A ju Halvmåneøya Seiland r T Tonefjellet o 933 t Tusenøyane 4 West-Telemark Hornsundtind S 1430 Kirkenes SØRKAPP 5 Gaustatoppen LAND Stabbursdalen Lakselv Hopen Nasjonalpark 6 Rauland & Haukeli Sørkappøya Alta FJORD NORWAY Page 12-16 Ringvassøya NORWEGIAN SEA Karasjok 7 Stavanger & -

Norwegian Winter and Summer

GUIDED TOURS 2018 NORWEGIAN WINTER AND SUMMER EXPERIENCING NATURE – ENRICHMENT FOR LIFE dntoslo.no INFORMATION FOR GRADING OF GUIDED TOURS WINTER TOURS Our guided tours differ in grade based on type of terrain and tour length / duration, summer or winter. When you are going to choose a tour, it is important to join a tour that is suitable to your WELCOME TO Climate, weather and ski conditions physical abilities. Our tour grading system is meant to give you an idea of the level of fitness and Norway shares the same latitude as Alaska, hiking/skiing experience that is required for each tour. In general, you should be able to hike/ski in Greenland and Siberia, but compared to these areas, different types of terrain, from relatively flat and soft to more hilly and rocky, carrying a backpack, Norway has a more pleasant climate. However the even in bad weather. Our grading scale takes into consideration both tour length and type of terrain: winter can be quite stormy and the weather change GUIDED TOURS 2018 able. To prepare for this, please follow our recom Easy mended equipment list (p. 23). Winter temperatures Length: Day tours from the lodge / cabin or easy day events for everyone. The tour length can in the mountains in the southern part of Norway usually be adjusted to the skill level of the participants. The Norwegian Trekking Association (DNT Oslo og Omegn) organizes guided ski- and hiking tours. vary from about 5 to 20°C. Windy weather lowers Terrain: The tour is on relatively flat terrain. The planned route will mostly follow the waymarked the temperature dramatically. -

In the Home of Giants Trekking Through Norway’S Jotunheimen National Park

24 » On Trail November + December 2009 » Washington Trails www.wta.org Further Afield » In the Home of Giants Trekking through Norway’s Jotunheimen National Park Lake Langvatnet, otunheimen National Park in south-central Norway offers spectacular hiking through (Day 8). Photo by high, open, lake-strewn country. Here reside the highest peaks of Europe north of the Jean Wahlstrom. Alps. Mountain hotels spaced a day’s walk apart make the trek all the more enjoy- able. With these “hotels” providing beds and all meals, one can go “hut-hopping” with a light pack. Everyone seems to speak English, so there is no language barrier . Thirty years ago, my wife, Cecile, and I hiked the standard Jotunheimen loop together. This past summer, we returned with six friends (Gary, Jack, Jean, Rebecca, Shane and Steve), retracing many of our earlier steps during the second week of July. This article will describe both the basic loop and the logistics for doing this trip, to enable U.S. hik- Jers to enjoy this exciting area. The basic Jotunheimen loop starts at Lake Gjende, a long, narrow lake running east to west; at its eastern end is Gjendesheim, where the hiking starts. Halfway down the lake, on its north side, is Memurubu, and at its western end is Gjendesbu; all of these hotels are linked by early morning and late afternoon ferry service. A day’s hike north of Lake Gjende are three other hotels, each a day’s hike from each other: Glitterheim, Spiterstulen, and Leirvassbu, running east to west. The basic loop runs counterclockwise: Gjendesheim, Memurubu, Glitterheim, Spiterstulen, Leirvassbu, and Gjendes- bu. -

JOTUNHEIMEN 2° 3° Jotunheimen Nasjonalpark Jotunheimen Nasjonalpark

JOTUNHEIMEN 2° 3° Jotunheimen nasjonalpark Jotunheimen nasjonalpark Utsyn frå Galdhøpiggen (TD) Jotnar på Noregs tak «Jøtunheimen» døypte Aasmund Olavsson Vinje fjella her i 1862, inspirert av det ville landskapet og norrøn mytologi. Jotnane – trolla – har heimen sin her. Jøtunheimen vart seinare til Jotunheimen, og det namnet brukar vi i dag på dette mektige området med dei høgaste fjella i Nord-Europa. I Jotunheimen finst ei mengd brear, U-forma dalar som er gravne ut av breane og avsetningar frå breane si framrykking og tilbaketrekking i takt med endringar i klima. I nasjonalparken er det og eit mangfaldig plante- og dyreliv med rovdyr og rovfuglar. Utsikt mot Visdalen (BB) 4° 5° Jotunheimen nasjonalpark Jotunheimen nasjonalpark På Straumdalenskitur i Hurrungane (TD) Den første turisthytta på Leirvassbu T-merking (TD) NATUROPPLEVINGAR Friluftsliv klatreruter. Turen opp på Store Skagastølstind er tung, Jotunheimen har sidan 1800-talet vore eit av dei mest lang og vanskeleg, og krev klatring med klatreutstyr og populære områda i landet for fjellvandring. I dag er det tau. om lag 300 km med T-merkte fotturruter i Jotunheimen og Utladalen, med høve til både korte og lange fotturar. Hugs at å ferdast på bre kan vere farleg pga sprekker Om vinteren er det kvista skiløyper fleire stader. Mange i breen. All ferdsel på bre må skje med bruk av tau og av fjelltoppane eignar seg som turmål, men ein god del anna sikringsutstyr, samt kunnskap om korleis ein kan fjelltoppar krev klatring for å nå til topps. ferdast trygt på bre. Ein kan og leige seg ein fjellførar. Fleire selskap og turlag tilbyr organiserte turar i nasjonal- I utkanten og inne i nasjonalparken er det ei rekkje parken, både enklare ski- og fotturar og meir krevjande betente og ubetente turisthytter. -

Detailed Itinerary

Lake Gjende, Jotunheimen National Park TREKKING FJORDS AND NATIONAL PARKS OF NORWAY, AUGUST 18 – SEPTEMBER 1, 2019, TRIP DESCRIPTION Norway, the Land of the Midnight Sun, a place where you will find some of the most magical mountain landscapes in the world. Take a walk on the wild side and discover why the locals can’t get enough of nature. After a long winter, people of all age groups and social backgrounds head outdoors and go trekking in the mountains, along the coast, fjords or in the forests. The varied scenery, from popular marked trails and tourist attractions to wild and untamed mythical landscapes, has earned Norway a well-deserved reputation as a major hiking destination in Europe. You will meet a kind and proud people who will enthusiastically share with you their love of the mountains. Norway shares a common border with Sweden on the east and in the north with Finland and Russia. Less than 4% of the Norway’s land is cultivated, leaving 96% as a playground for the outdoor enthusiast. The population density of Norway is the lowest of any country in Europe, where most of the 4 ½ million Norwegians live along the southern coast. We will start our adventure in Norway’s second largest city, the western coastal town of Bergen. As a university town and cultural center, it boasts a plethora of museums as well as several theatres and a renowned philharmonic orchestra. Set on a peninsula surrounded by seven mountains, Bergen’s history is closely tied to the sea. Hiking between Mount Ulriken and Mount Fløyen with Bergen below Our first whole day in Bergen we will have the opportunity, depending on the weather, to hike between Mount Ulriken and Mount Fløyen, on a high plateau with spectacular views of Bergen below. -

TINDERANGLER Medlemsblad for DNT Valdres Nr

VALDR T E N S D TINDERANGLER Medlemsblad for DNT Valdres Nr. 2 – 2016 – Årgang 35 1982 1 Foto: Yngve Ask - Bekledning: Fjellreven Yngve Foto: TINDERANGLER MEDLEMSBLAD FOR DNT VALDRES Årgang 35 Oktober 2016 Heimeside: www.dntvaldres.no Redaktør: Tor Harald Skogheim Tlf./mail: 61 34 05 11 / 996 90 793/ [email protected] Layout: Kjell Ivar Andersen/Morten Helgesen Kodedalen - Uranostind Forenings-epost: [email protected] DU GÅR ALDRI ALEINE Barnas Turlag: [email protected] Available on the AppStore Trykk: 07 Gruppen AS Get it on Google play www.turapp.no/valdres Forside: På nymerka stier i Skrautvål Heimås. Foto: Trond Vatn INNHOLD: 4 Leder: Vi jubilerer! 7 Jubileumsmøte 10. oktober, med variert program 8 Turprogram for seinhøst/tidligvinter 10 Omtaler av årets turer – hovedlaget 40 Omtaler av årets turer – Barnas Turlag 44 Omtale av årets turer – Seniorgruppa 49 Rabattavtale med sportsforretninger 54 Omtale av årets turer – Vang Turlag 61 Tinderangling i Nepal STOFF til Tinderangler Alltid fint med bidrag, helst med bilder (som eigne filer, med god oppløsning). Frist: 15. januar 2017 til: [email protected] 2 3 Selvklebende Tekst streamers logo bildekor skilter storprint banner roll-up stempel gatebukk magnetskilt lay-out U. etg. Gjensidigegården når noe skal merkes . Tlf. 61 36 07 30 [email protected] vi hjelper deg med løsningen ! Fax. 61 36 16 15 www.skiltmanndekor.no Vi jubilerer! 2016 er jubileumsår for DNT Valdres, i sommer rundet vi 5 år. Vi kan imidlertid skryte av lange og solide tradisjoner og røtter. Valdres Tur- og Fjellsportlag ble etablert i 1982. De besluttet å søke om opptak i DNT i februar 2011. -

Hiking in Norway – South Hiking in Norway – South

HIKING IN NORWAY – SOUTH HIKING IN NORWAY – SOUTH THE 10 BEST MULTI-DAY TREKS by Ute Koninx About the Author Ute Koninx is a practised world traveller and outdoor enthusiast. She has lived in eight countries and four continents, with plentiful opportunities to feel lost and find her feet again, physically and metaphorically speak- ing. Her love for the Norwegian outdoors has been a continuous affair since living in the country between 2009 and 2015. She has since returned every year for her work as a tour guide as well as further explorations and research. Hiking in Norway – South is her latest project. For more back- ground information, visit www.iventureout.com. JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © Ute Koninx 2021 Second edition 2021 CONTENTS ISBN: 978 1 85284 975 7 This completely new guide replaces Map key ...................................................... 6 Walking in Norway (ISBN: 978 1 85284 230 7) by Constance Roos. Overview map ................................................. 9 Route summary table ........................................... 10 Printed in China on responsibly sourced paper on behalf of Latitude Press Ltd Author preface ................................................ 11 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 13 Norway – a hiker’s paradise ...................................... 13 All maps in this guide © Kartverket www.norgeskart.no Geography and geology ........................................