Reality Has Never Betrayed Me”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handbook for Courage and Encourage Chaplains

Handbook for Courage and EnCourage Chaplains Fortieth Anniversary Edition Trumbull, Connecticut 2020 Published with ecclesiastical permission Nihil obstat: Rev. Brian P. Gannon, STD Censor librorum Imprimatur: Most Rev. Frank J. Caggiano Bishop of Bridgeport 1 May 2020 The nihil obstat and imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the declarations agree with the content, opinions or statements expressed. Ministry to Persons with a Homosexual Inclination: Guidelines for Pastoral Care © 2006 United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington, D.C., 20017. All rights reserved. Handbook for Courage and EnCourage Chaplains Fortieth Anniversary Edition © 2020 Courage International, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system with- out permission in writing from the Copyright Holder. Permission is hereby granted for Courage and EnCourage chaplains to reproduce short excerpts for the use of members of their chapters during chapter meetings. To obtain copies of this Handbook, or to obtain permission for reprinting, excerpts or translations, contact the Copyright Holder at: Courage International, Inc. 6450 Main Street Trumbull, CT 06611 USA +1 (203) 803-1564 [email protected] In Loving Memory of Father John F. Harvey, O.S.F.S. (1918 — 2010) -

Parish Bulletin Board

January 7, 2018 W E L C O M E The Epiphany of the Lord The Mission of our parish is to serve our neighbors with Jesus, to pray in faith with Jesus, and to teach as His Church with Jesus, so “that all may have more abundant life.” (John 10:10). The Word of God, the Sacraments, and the Catechism of the Catholic Church are the instruments and standards of this work of evangelization and faith formation. Our Lady of Mount Carmel Pastoral Team 23–25 Newtown Avenue, Astoria, NY 11102 718.278.1834 • Fax 718.278.0998 Pastor [email protected] Msgr. Sean G. Ogle, V.F. Ext. 22 [email protected] Saturday (Upper Church) Follow me on twitter @theogleoffice 5:00pm (Vigil Mass) Parochial Vicars Father Peter Nguyen Ext. 20 Sunday (Upper Church) Father Wlad Kubrak Ext. 19 English Masses: 8:00am, 10:00am, 11:15am, 5:00pm* Pastor Emeritus (7:00pm during the Summer months from Memorial Day Father Ed Brady Ext. 18 weekend to Labor Day weekend, inclusive) In Residence Misa en Español: 12:30pm Father John Harrington K.H.S., Ext. 28 Sunday (Lower Church) Father Joseph Pham Ext. 15 9:00am (Italian) Deacon 10:30am (Czech–Slovak) Ruben Mendez 3:00pm (Vietnamese) Pastoral Worker Chin Nguyen Ext. 23 Monday–Friday (Lower Church) Coordinator of Religious Education 8:00am and 12:00pm Nelly Gutierrez Ext. 14 Saturday: 8:00am [email protected] Parish Office Hours/ Horario de la Oficina Parish Outreach Coordinator Weekdays: 9:30am-12:00 Noon and 1:00pm-8:30pm Denise Dollard 718.721.9020 Saturday: 9:00am-12:00 Noon Parish Secretary/Bookkeeper CHAPEL OF ST. -

Pastors and the Ecclesial Movements

Laity Today A series of studies edited by the Pontifical Council for the Laity PONTIFICIUM CONSILIUM PRO LAICIS Pastors and the ecclesial movements A seminar for bishops “ I ask you to approach movements with a great deal of love ” Rocca di Papa, 15-17 May 2008 LIBRERIA EDITRICE VATICANA 2009 © Copyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana 00120 VATICAN CITY Tel. 06.698.85003 - Fax 06.698.84716 ISBN 978-88-209-8296-6 www.libreriaeditricevaticana.com CONTENTS Foreword, Cardinal Stanisław Ryłko ................ 7 Address of His Holiness Benedict XVI to the participants at the Seminar ............................. 15 I. Lectures Something new that has yet to be sufficiently understood . 19 Ecclesial movements and new communities in the teaching of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, Cardinal Stanisław Ryłko . 21 Ecclesial movements and new communities in the mission of the Church: a theological, pastoral and missionary perspective, Msgr. Piero Coda ........................ 35 Movements and new communities in the local Church, Rev. Arturo Cattaneo ...................... 51 Ecclesial movements and the Petrine Ministry: “ I ask you to col- laborate even more, very much more, in the Pope’s universal apostolic ministry ” (Benedict XVI), Most Rev. Josef Clemens . 75 II. Reflections and testimonies II.I. The pastors’ duty towards the movements . 101 Discernment of charisms: some useful principles, Most Rev. Alberto Taveira Corrêa . 103 Welcoming movements and new communities at the local level, Most Rev. Dominique Rey . 109 5 Contents Pastoral accompaniment of movements and new communities, Most Rev. Javier Augusto Del Río Alba . 127 II.2. The task of movements and new communities . 133 Schools of faith and Christian life, Luis Fernando Figari . -

'I Thank God Every Single Day'

Inside See our Catholic Schools Week Criterion Supplement, pages 1B-16B. Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com January 27, 2012 Vol. LII, No. 15 75¢ HHS delays, but does not ‘I thank God every single day’ change, rule Unwed mother on contraceptive who chose life MaryPhoto by Ann Garber coverage shares her WASHINGTON (CNS)—Although Catholic leaders vowed to fight on, the Obama moving story administration has turned down repeated requests from Catholic bishops, hospitals, schools and charitable organizations to revise at annual its religious exemption to the requirement that all health plans cover contraceptives and Respect Life sterilization free of charge. Instead, Kathleen Sebelius, secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Rally in Services, announced on Jan. 20 that non-profit groups Indianapolis that do not provide contraceptive By Mary Ann Garber coverage because of their religious beliefs Tears filled her eyes as Liz Carl spoke will get an additional of her beautiful 4-year-old son, Braden, year “to adapt to this who was conceived during a rape when she new rule. was only 17. “This decision was Smiling through made after very her tears, she took a careful consideration, deep breath and including the described how God Kathleen Sebelius important concerns helped her as a rape some have raised survivor to choose about religious liberty,” Sebelius said. life then place her “I believe this proposal strikes the baby in an open appropriate balance between respecting adoption with religious freedom and increasing access to wonderful parents. important preventive services.” Liz Carl “He is the love But Cardinal-designate Timothy of my life,” the M. -

H Ope Does Not D Isappoint

H OPE DOES NOT D ISAPPOINT E XERCIISES OF THE F RATERNITY OF C OMMUNION AND L IBERATION R IMINI 2005 Cover: Giotto, The Raising of Lazarus (detail), Lower Church of San Francesco, Assisi. © 2005 Fraternità di Comunione e Liberazione Traduzione dall’italiano di Susan Scott e don Edo Mörlin Visconti Edizione fuori commercio Finito di stampare nel mese di luglio 2005 presso Ingraf, Milano The Vatican, April 27, 2005 Reverend Fr Julián Carrón President of the Fraternity of Communion and Liberation Reverend Father, I have the joy of transmitting to you and to the Fraternity of Communion and Liberation a particular greeting from His Holiness Benedict XVI, on the occasion of the “Spiritual Exercises,” to take place in Rimini on April 29-30 this year. With the memory of the mov- ing funeral of the late Fr Luigi Giussani in Milan Cathedral still alive his heart, the Holy Father, participating spiritually in the fervour of these days of reflection and prayer guided by you, he ardently wishes that they bear fruits of ascetic renewal and ardent apostolic and mis- sionary zeal. The theme of the meditations is significant: Hope. How relevant it is in our time that we understand the value and importance of Christian hope, which sinks its roots in a simple, unhesitant faith in Christ and his word of salvation! Our dear Fr Giussani nourished himself with this hope, and your esteemed Fraternity means to contin- ue the journey in his footsteps. Your Founder passed away shortly before our beloved Holy Father John Paul II. Both were ardent wit- nesses of Christ and they leave us the heritage of a witness of total dedication to the “hope that does not disappoint us” (Rom 5:5), that hope which the Holy Spirit pours into the hearts of the faithful by giv- ing them the love of God. -

Emergenza Esclusi

01_PRIMA PARTE SV 123_p_1-34.QXD_Layout 1 07/08/15 13:27 Pagina 1 Emergenza Esclusi The Emergency of the Socially Excluded 01_PRIMA PARTE SV 123_p_1-34.QXD_Layout 1 07/08/15 13:27 Pagina 2 01_PRIMA PARTE SV 123_p_1-34.QXD_Layout 1 07/08/15 13:27 Pagina 3 Pontificiae Academiae Scientiarvm Scripta Varia 123 The Proceedings of the Workshop on Emergenza Esclusi The Emergency of the Socially Excluded 5 DECEMBER 2013 Edited by Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo EX AEDIBVS ACADEMICIS IN CIVITATE VATICANA • MMXV 01_PRIMA PARTE SV 123_p_1-34.QXD_Layout 1 07/08/15 13:27 Pagina 4 The Pontifical Academy of Sciences Casina Pio IV, 00120 Vatican City Tel: +39 0669883195 • Fax: +39 0669885218 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.pas.va The opinions expressed with absolute freedom during the presentation of the papers of this meeting, although published by the Academy, represent only the points of view of the participants and not those of the Academy. ISBN 978-88-7761-109-3 © 2015 Libreria Editrice Vaticana All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, photocopying or otherwise without the expressed written permission of the publisher. PONTIFICIA ACADEMIA SCIENTIARVM • VATICAN CITY 01_PRIMA PARTE SV 123_p_1-34.QXD_Layout 1 07/08/15 13:27 Pagina 5 Ustedes hoy empezaron a “romper” los esquemas porque mien- tras... los esquemas normales porque por ahí mientras algunos dor- mían, ustedes ya estaban caminando, estaban rompiendo los esquemas con los gritos. Mientras algunos por ahí estaban reunidos a ver como podían hacer para poder tener más dinero, más poder, o más influencias, ustedes estaban diciendo que el Amor es Servi- cio; y que lo único que vale en la vida es vivir para los demás. -

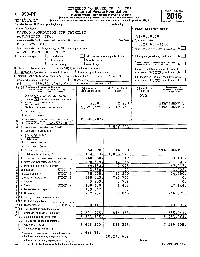

2016 990 PF Form

EXTENDED TO NOVEMBER 15, 2017 Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Department of the Treasury ~ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2016 Internal Revenue Service ~ Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. inen o ~uh11c n~ec ion For calendar year 2016 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number RASK OB FOUNDATION FOR CATHOLIC ACTIVITIES INC. 51-0070060 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail 1s not delivered to street address) IRoom/suite B Telephone number P.O. BOX 4019 {302} 655-4440 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ..... o WILMINGTON, DE 19807 G Check all that apply: D Initial return D Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ........ o D Final return D Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test • D Address chanoe D Name chanoe check here and attach computation ..... o H Check type of organization: 00 Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated D Section 4947(a)( 1l nonexempt charitable trust D Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ..... o I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Dcash [][]Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part II, col. -

Unity Transcriptions by Karen Kaffenberger Copyediting and Layout by Deep River Media, LLC

Proceedings of the New York Encounter 2018 An “Impossible” Unity An “Impossible” Transcriptions by Karen Kaffenberger Copyediting and layout by Deep River Media, LLC Human Adventure Books An "Impossible" Unity Proceedings of New York Encounter 2018 Crossroads Cultural Center This edition © 2018 Human Adventure Books An “Impossible” Unity We naturally yearn for unity and long to be part of a real community: life blossoms when it is shared. And yet, we live in an age of fragmentation. At the social level, we suffer profound divisions among peoples and religions, and our country is ever more polarized along ideological lines, corroding our unity. At the personal level, we are often estranged from our communities, family members, and friends. When we discover that someone doesn’t think the way we do, we feel an embarrassing distance, if not open hostility, that casts a shadow on the relationship. As a result, either we become angry or we avoid controversial issues altogether, and retreat into safe territories with like-minded people. But the disunity we see around us often begins within ourselves. We are bombarded by images of what we are “supposed” to be, but they generally do not correspond to who we really are. In fact, our truest self seems to escape us. The full scope of our humanity, with all its vast and profound needs and desires, may suddenly emerge, elicited by memories, thoughts or events, but usually quickly fades, without lasting joy or real change. And unless our relationships are rooted in the common experience of such humanity, we don’t even have real dialogue; we just chat, gossip, text or argue. -

Traces Magazine 11/2016 3 MB

COMMUNION AND LIBERATION INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE 2016 10 VOL.TRACES 18 LITTERAE COMMUNIONIS A PATH THAT NEVER ENDS As the Jubilee is closing its doors we treasure the embrace of mercy that we have experienced during the last year. A concrete reality possible in every moment of life and of history. CoverTraces102016_sel.indd 1 09/11/16 11:40 CONTENTS November, 2016 Vol.18 - No. 10 Communion and Liberation International Magazine - Vol. 18 CLOSE UP Editorial Offi ce: Via Porpora, 127 - 20131 Milano Tel. ++39(02)28174400 A YEAR 6 Fax ++39(02)28174401 E-mail: [email protected] WITHOUT AN END Internet:www.tracesonline.org The Jubilee Year of Mercy will conclude on Editor (direttore responsabile): November 20th. But “the work to open ourselves Davide Perillo to mercy” will not stop here. From following the Vice-editor: Pope to the refugees who “refl ect what we are,” Paola Bergamini we hear from FR. MAURO-GIUSEPPE LEPORI, Editorial Assistant: Abbot General of the Cistercian Order. Anna Leonardi From New York, NY: Holly Peterson Editorial A True Dialogue 3 Graphic Design: G&C, Milano Davide Cestari, Lucia Crimi Letters Edited by Paola Bergamini 4 Photo: GettyImages: Cover, 20, 22-23 Close up Jubilee A Year Without An End by Alessandra Stoppa 6 Publishers (editore): Società Coop. Edit. Nuovo Mondo Via Porpora, 127 - 20131 Milano CL life School of Community Only for Living Reg. Tribunale di Milano n°. 740 - 28 ottobre 1998 by A. Leonardi, P. Perego, A. Stoppa 12 Iscrizione nel Registro degli Operatori Uganda A New Chapter in Life by Paolo Perego 17 di Comunicazione n. -

Envisioning Futures for the Catholic Church Hellemans, Staf; Jonkers, Peter

Tilburg University Envisioning Futures for the Catholic Church Hellemans, Staf; Jonkers, Peter Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hellemans, S., & Jonkers, P. (2018). Envisioning Futures for the Catholic Church. Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. sep. 2021 Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series VIII, Christian Philosophical Studies 23 Envisioning Futures for the Catholic Church Edited by Staf Hellemans & Peter Jonkers The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2018 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Gibbons Hall B-20 620 Michigan Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Names: Hellemans, Staf, editor. -

The Role of Mary in the New Ecclesial Communities in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

Marian Library Studies Volume 31 Mary in the Consecrated Life Article 23 2013 The Role of Mary in the New Ecclesial Communities in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Danielle Peters University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_studies Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Peters, Danielle (2013) "The Role of Mary in the New Ecclesial Communities in the Twentieth and Twenty- First Centuries," Marian Library Studies: Vol. 31, Article 23. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_studies/vol31/iss1/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. FROM MONOGRAM TO MISSION A SPECIALDEVOTION Communities Entrusted With A Special Marian Devotion Devotion to the Heart of Mary Holy Card Bouass6-Lebel Paris, 1 850 Tm Ror,n or Mmv rN TrrE Nnv Eccr,EsrAL Comuuurtrns oF TrrR TVrrvrmru mm TVnr.srr-FrRsr Cnlwunrns Introduction Ten popes,t Vatican Il, the renewal of the laws of canonical discipline, a drastic change in the pastoral sphere of the Church as well as the confrontation with radical social, political, and ecumenical changes in contemporary society are but a few details of the colorful and multifaceted portrayal of the Church in the 20th and at the dawn of the 21st century. The social and cultural hap- penings which have rapidly come about in modem society have also had a no- ticeable toll on the consecrated life in the church. -

The Life I Now Live in the Flesh I Live by Faith In

THE LIFE I NOW LIVE IN THE FLESH I LIVE BY FAITH IN THE SON OF GOD EXERCISES OF THE FRATERNITY OF COMMUNION AND LIBERATION Rimini 2002 Cover: Raphael, Saint Cecilia Altarpiece, detail of St Paul, Bologna, Pinacoteca © 2002 Fraternità di Comunione e Liberazione Traduzione dall'italiano di Susan Scott e don Edo Mòrlin Visconti Edizione fuori commercio Finito di stampare nel mese di luglio 2002 presso Ingraf, Milano Vatican City On the occasion of the Spiritual Exercises of the Fra- ternity of Communion and Liberation in Rimini on the theme "The life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God," the Supreme Pontiff charges Your Eminence with transmitting to the organizers and par- ticipants his warm good wishes and greetings, express- ing his pleasure at the timely initiative, and in hopes that this may arouse renewed adherence to Christ and a growing commitment to witnessing to the Gospel, in- vokes abundant heavenly grace and gladly sends to Your Eminence who presides over the Eucharistic cele- bration and all those present the desired apostolic blessing. Cardinal Angelo Sodano, Secretary of State Friday eveningy May 3 M OPENING GREETINGS During the entrance and exit: Johannes Brahms, Symphony no. 4 in E minor, op. 98, Riccardo Muti - Philadelphia Orchestra "Spirto Gentil," Philips FrPino (Stefano Alberto). I would like to greet, together with each of you, our friends in eighteen countries who are with us by satellite link. In the com- ing weeks, another thirty-six countries will follow these Exercises. Being in this enormous space, which affords us an impressive sight, must not make us forget that in this instant each one of us is personally face to face with his Destiny; indeed, our gathering is conceived precisely as an aid so that each one of us may stand before that Presence to whom each of us is freely giving his life.