Herdsmen Around Loughrea in the Late 19Th Century[1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

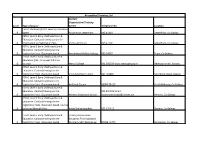

Accredited Training List Contact Organisation/Training Level Type of Course Centre Telephone No

Accredited Training List Contact Organisation/Training Level Type of Course Centre Telephone No. Location FETAC Childcare (NCVA Level 5) Classroom 5 based Youthreach Letterfrack 095 41893 Letterfrack, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre for 5 information on registration fees. VTOS Letterfrack 095 41302 Letterfrack, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 5 registration fees. Classroom based. Archbishop McHale College 093 24237 Tuam, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education (PLC - One year full time 5 course) Mercy College 091 566595 www.mercygalway.ie Newtownsmith, Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 5 registration fees. Classroom based. VTOS Merchants Road 091 566885 Merchants Road, Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 5 registration fees. Classroom based. Ard Scoil Chuain 09096 78127 Castleblakeney, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 091 844159 Email: 5 registration fees. Classroom based. Athenry Vocational School [email protected] Athenry, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - registration fees. Classroom based. Course 5 delivered through Irish. Ionad Breisoideachais 091 574411 Rosmuc, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Galway Roscommon Education. Contact training centre - Education Training Board 5 registration fees. Classroom based. (formerly VEC) Ballinasloe 09096 43479 Ballinasloe, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Galway Roscommon Education. Contact training centre - Education Training Board 5 registration fees. Classroom based. (formerly VEC) Oughterard 091 866912 Oughterard, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. -

Bride Street, Loughrea, Co. Galway

FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY Bride Street, Loughrea, Co. Galway Bride Street, Loughrea, Co. Galway 459.9 Sq M (4,950 Sq Ft) Property Highlights Contact • Income producing asset centrally located within Loughrea George Brady Town Email: [email protected] Tel: 091 569 181 • Excellent site extending to Circa 0.25 acres Sean Coyne • Good profile onto busy street Email: [email protected] • Neighbouring businesses include Department of Social Tel: 091 569 181 Protection, Paul Byron Shoes, Subway and numerous retail / office occupiers. Cushman & Wakefield • Currently occupied by Michael Regan Auctioneering and 2 Dockgate, Headstones Dock Road, Galway Ireland • Tenant Not Affected Tel: 091-569181 cushmanwakefield.ie The Location Schedule of Accommodation The property for sale is located in the town of Unit Sq M Sq Ft Loughrea, which itself is a large market town located Ground 246.7 2,655 in east County Galway. First 213.2 2,295 More specifically the subject property is located on Total 459.9 4,950 the north side of Bride Street at its junction with Main Street. Occupier Loughrea is located approximately 35 km south east of Galway City on the northern shore of Lough Rea The property is occupied by Michael Regan and is located at the junction of the N6, Old Dublin to Auctioneers / Headstones for €9,600 per annum. Galway Road and the N66 National Secondary Route to Gort and Limerick. Loughrea is also accessible from the west and east of the country via the newly Local Authority Rates completed M6 Motorway. €5,495.67 per annum The town has developed into a busy urban centre which provides an important market and commercial Title centre for the east and south of the county. -

Silver Strand Silverstrand Has a Safe, Shallow, Sandy Beach of Approximately 0.25Km Bounded on One Side by a Cliff and the Other by Rocks

Silver Strand Silverstrand has a safe, shallow, sandy beach of approximately 0.25km bounded on one side by a cliff and the other by rocks. It is particularly popular with and suitable for young families. It faces directly into Galway Bay giving spectacular views. There is a promenade with parking capacity for about 60 vehicles. It is suitable for swimming at low tide but the beach is largely covered during high tides. It is lifeguarded during the summer months. Blue Flag standard (2005). Barna Golf and Country Club Corbally, Barna, Co. Galway Telephone: +353 91 592677 Fax: +353 91 592674 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.bearnagolfclub.com Located approx. 8km from Galway, and 3km north of Bearna village, this golf course is set in typical rugged Connemara countryside with fairways constructed between rocks and heather. The course was designed to suit all abilities. Bearna golf course is already being hailed as one of Ireland's finest. The inspired creativity of its designer R.J. Browne in the siting of tees and sand-based greens in the celebrated beauty of West of Ireland's Connemara landscape has produced a course of glamorously porportioned holes. Water comes into play at thirteen of the eighteen holes, each one boasting unique features which together test the golfer's total repertoire of skills. The final holes especially provide a spectacular finish to a satisfying and memorable experience. Caddy hire available. Dress code is neat & casual. Full canteen facilities available with full bar menu and restaurant. Course designed by Robert J Browne. Course length (m): 6174 Athenry Golf Club Palmerstown, Oranmore, Co. -

Thatchers in Ireland (21.07.2016)

Thatchers in Ireland (21.07.2016) Name Address Telephone E-mail/Web Gerry Agnew 23 Drumrammer Road, 028 2587 82 41 Aghoghill, County Antrim, BT42 2RD Gavin Ball Kilbarron Thatching Company, 061 924 265 Kilbarron, Feakle, County Clare Susanne Bojkovsky The Cottage, 086 279 91 09 Carrowmore, County Sligo John & Christopher Brereton Brereton Family Thatchers, 045 860 303 Moods, Robertstown, County Kildare Liam Broderick 12 Woodview, 024 954 50 Killeagh, County Cork Brondak Thatchers Suncroft, 087 294 45 22 Curragh, 087 985 21 72 County Kildare 045 860 303 Peter Brugge Master Thatchers (North) Limited, 00 44 (0) 161 941 19 86 [email protected] 5 Pines Park, www.thatching.net Lurgan, Craigavon, BT66 7BP Jim Burke Ballysheehan, Carne, Broadway, County Wexford Brian Byrne 6 McNally Park, 028 8467 04 79 Castlederg, County Tyrone, BT81 7UW Peter Childs 27 Ardara Wood, 087 286 36 02 Tullyallen, Drogheda, County Louth Gay Clarke Cuckoo's Nest, Barna, County Galway Ernie Clyde Clyde & Reilly, 028 7772 21 66 The Hermitage, Roemill Road, Limavady, County Derry Stephen Coady Irish Master Thatchers Limited, 01 849 42 52 64 Shenick Road, Skerries, County Dublin Murty Coinyn Derrin Park, Enniskillen, County Fermanagh John Conlin Mucknagh, 090 285 784 Glassan, Athlone, County Westmeath Seamus Conroy Clonaslee, 0502 481 56 County Laois Simon Cracknell; Cool Mountain Thatchers, 086 349 05 91 Michael Curtis Cool Mountain West, Dunmanaway, County Cork Craigmor Thatching Services Tullyavin, 086 393 93 60 Redcastle, County Donegal John Cunningham Carrick, -

Board Order ABP-306028-19 Decision

Board Order ABP-306028-19 Planning and Development Acts 2000 to 2019 Planning Authority: Galway County Council Planning Register Reference Number: 19/599 Appeal by John Finucane of Omey Island, Claddaghduff, Connemara, County Galway against the decision made on the 22nd day of November, 2019 by Galway County Council to grant subject to conditions a permission to Olive Butler care of Ciaran Flynn of Letterfrack, County Galway in accordance with plans and particulars lodged with the said Council. Proposed Development: Retention of an existing single storey house, as constructed, floor area 85 square metres which previously had planning permission at Gooreenatinny, Omey Island, County Galway. Decision GRANT permission for the above proposed development in accordance with the said plans and particulars based on the reasons and considerations under and subject to the condition set out below. ______________________________________________________________ ABP-306028-19 An Bord Pleanála Page 1 of 3 Matters Considered In making its decision, the Board had regard to those matters to which, by virtue of the Planning and Development Acts and Regulations made thereunder, it was required to have regard. Such matters included any submissions and observations received by it in accordance with statutory provisions. Reasons and Considerations Having regard to the zoning objective of the area, the design, layout and scale of the development proposed for retention and the pattern of development in the area, it is considered that, subject to compliance with the condition set out below, the development to be retained would not seriously injure the visual amenities of the area or the residential amenities of property in the vicinity. -

County Galway

Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee No. 1 Report 2018 County Galway ISLAND BALLYMOE Conamara North LEA - 4 TEMPLETOGHERKILCROAN ADDERGOOLE BALLINASTACK INISHBOFIN TOBERADOSH BALLYNAKILL DUNMORE NORTH TOBERROE INISHBOFIN MILLTOWN BOYOUNAGH Tuam LEA - 7 DUNMORE SOUTH RINVYLE CARROWNAGUR GLENNAMADDY DOONBALLY RAHEEN CUSHKILLARY FOXHALLKILBENNAN CREGGS AN ROS KILTULLAGH CLEGGAN LEITIR BREACÁIN KILLEEN SILLERNA KILSHANVY CLONBERN CURRAGHMORE BALLYNAKILL AN FHAIRCHE SILLERNA CARROWREVAGH CLOONKEEN KILLERORAN BELCLARETUAM RURAL SHANKILL CLOONKEEN BEAGHMORE LEVALLY SCREGG AN CHORR TUAM URBAN CLIFDEN BINN AN CHOIRE AN UILLINN CONGA DONAGHPATRICK " BALLYNAKILL Clifden " DERRYLEA Tuam HILLSBROOK CLARETUAM KILLERERIN MOUNT BELLEW HEADFORDKILCOONA COOLOO KILLIAN ERRISLANNAN LETTERFORE CASTLEFFRENCH DERRYCUNLAGH KILLURSA BALLINDERRY MOYNE DOONLOUGHAN MAÍROS Oughterard CUMMER TAGHBOY KILLOWER BALLYNAPARK CALTRA " KILLEANYBALLINDUFF BUNOWEN ABBEY WEST CASTLEBLAKENEY AN TURLACH OUGHTERARD ABBEY EASTDERRYGLASSAUN CILL CHUIMÍN ANNAGHDOWN CLOCH NA RÓN KILMOYLAN MOUNTHAZEL CLONBROCK CLOCH NA RÓN WORMHOLE Ballinasloe LEA - 6 RYEHILL ANNAGH AHASCRAGH ABHAINN GHABHLA LISCANANAUN COLMANSTOWN EANACH DHÚIN DEERPARK MONIVEA BALLYMACWARD TULAIGH MHIC AODHÁIN LEACACH BEAG BELLEVILLE TIAQUIN KILLURE AN CNOC BUÍ CAMAS BAILE CHLÁIR CAPPALUSK SLIABH AN AONAIGH KILCONNELL LISÍN AN BHEALAIGH " Ballinasloe MAIGH CUILINNGALWAY RURAL (PART) SCAINIMH LEITIR MÓIR GRAIGABBEYCLOONKEEN KILLAAN BALLINASLOE URBAN CEATHRÚ AN BHRÚNAIGHAN CARN MÓR BALLINASLOE RURAL LEITIR MÓIR CILL -

This Is Galway Census 2011 – Highlights for County Galway

Prepared by Community, Enterprise & Economic Development Unit Galway County Council This is Galway Census 2011 – Highlights for County Galway 1 Table of Contents page Summary 3 Population 5 Age Profile 9 Place of Birth, Nationality and Foreign Languages 11 Deprivation Index 13 The Labour Force and Unemployment 17 Socio-economic Group and Social Class 20 Education 26 Travel Patterns and Car Ownership 30 Computer Ownership & Internet Access 34 Housing and Occupancy 35 2 Summary Living Arrangements & Family Units There are 60,952 private households in County Galway with an average of 2.8 persons per household. A husband and wife with children make up the largest portion of households in County Galway at 37.1% followed by one person households at 23.1% and husband and wife at 15.4%. Older females are more likely to live alone that older males. 51.6% of the population of County Galway were single in 2011. 40.3% of the population of County Galway were married in 2011. Place of Birth, Nationality and Foreign Languages The proportion of non Irish people living in County Galway has risen from 8.1% in 2006 to 14.7% in 2011. County Galway has a lower proportion of non Irish people (14.7%) than Galway City (25%) and the State (16.9%). Persons born in England and Wales made up the highest proportion of non Irish residents in County Galway at 6.7%. Americans were second at 3.1% and Poles were third at 1.8%. Ethnicity, Irish Language and Religion Galway City has a higher proportion of Travellers at 2.3% of the total usual resident population than County Galway at 1.4% and the state average at 0.6%. -

Galway County Development Board - Priority Actions 2009-2012

Galway CDB Strategy 2009-2012, May 2009 Galway County Development Board - Priority Actions 2009-2012 Table of Contents Galway County Development Board ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Priority Actions 2009-2012.............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Galway County Development Board........................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Format of Report.............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Section 1: Priority Strategy - Summary....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Section 2 - Detailed Action Programme..................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Tracing Your Roots in North-West Connemara

Tracing eour Roots in NORTHWEST CONNEMARA Compiled by Steven Nee This project is supported by The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development - Europe investing in rural areas. C O N T E N T S Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... Page 4 Initial Research (Where to begin) ............................................................................................................... Page 5 Administrative Divisions ............................................................................................................................... Page 6 Useful Resources Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. Page 8 Census 1901/1911 ......................................................................................................................................... Page 8 Civil/State Records .................................................................................................................................... Page 10 National Repositories ................................................................................................................................. Page 10 Griffiths Valuation ........................................................................................................................................ Page 14 Church Records ......................................................................................................................................... -

Mountbellew Girls a Tale of Two Workhouse Emigrants 1852

IRELAND TO AUSTRALIA…. A TALE OF TWO WORKHOUSE EMIGRANTS Archival treasures unlock a key to the past for two families. Two Western Australians searching for the origins of their great-great grandmothers who arrived in Freemantle in 1853 trace them to the workhouse in Mountbellew, County Galway. Galway County Council Archives was able to help two thrilled and delighted researchers confirm and establish with some certainty that their great-great grandmothers had travelled as part of a group of 30 young girls, who received assisted passage, from the workhouse to Western Australia. Bill Marwick and Kerryn Ferraro have for many years being independently searching for their ancestors, and had already found out a great deal. However, one tiny piece of information, relating to when and how the girls emigrated remained something of a mystery. Recently a small, but significant, piece of their interlinking family histories’ jigsaw has been found in the Mountbellew Board of Guardian Minutes. Bill had been carrying out his family research for many years and had travelled to Ireland on several occasions in the hunt to track down the origins of his great grandmother, Mary Ann Taylor. Bill is a wonderful story teller and indeed recounts his search with great ease and flare in his book on his family, ‘The Marwicks of York’. He had already established that Mary Ann had arrived in Freemantle, Western Australia in May 1853. He had found her name in the shipping manifest for the Palestine, which left Plymouth, England, on 29th November 1852. He knew from her marriage certificate that she was from Castleblakeney, outside Ballinasloe; though at first he thought it was Castleblaney in County Monaghan! Bill’s family have the most wonderful photograph of Mary Ann, taken they believe just before she left Ireland or Plymouth. -

Registration Districts of Ireland

REGISTRATION DISTRICTS OF IRELAND An Alphabetical List of the Registration Districts of Ireland with Details of Counties, SubDistricts and Adjacent Districts Michael J. Thompson [email protected] © M. J. Thompson 2009, 2012 This document and its contents are made available for non‐commercial use only. Any other use is prohibited except by explicit permission of the author. The author holds no rights to the two maps (see their captions for copyright information). Every effort has been made to ensure the information herein is correct, but no liability is accepted for errors or omissions. The author would be grateful to be informed of any errors and corrections. 2 Contents 1. Introduction … … … … … … … Page 3 a. Chapman code for the counties of Ireland b. Maps of Ireland showing Counties and Registration Districts 2. Alphabetical listing of Registration Districts … … … Page 6 giving also sub‐districts contained therein, and adjacent Registration Districts 3. Registration Districts listed by County … … … Page 17 4. Alphabetical listing of Sub‐Districts … … … … Page 20 Appendix. Registration District boundary changes between 1841 and 1911 … Page 30 First published in 2009 Reprinted with minor revisions in 2012 3 1. Introduction Civil registration of births, marriages and deaths commenced in Ireland in 1864, though registration of marriages of non‐Roman Catholics was introduced earlier in 1845. The Births, marriages and deaths were registered by geographical areas known as Registration Districts (also known as Superintendent Registrar’s Districts). The boundaries of the registration districts followed the boundaries of the Poor Law Unions created earlier under the 1838 Poor Law Act for the administration of relief to the poor. -

Archaeological Assessment of Route Options for the N83 Roadway in Dunmore County Galway

ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF ROUTE OPTIONS FOR THE N83 ROADWAY IN DUNMORE COUNTY GALWAY February 2020 Through Time Ltd. Professional Archaeological Services Old church Street, Athenry, Co. Galway www.throughtimeltd.com Archaeological & Cultural Heritage Assessment of route options in Dunmore, County Galway. ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF ROUTE OPTIONS FOR THE N83 ROADWAY IN DUNMORE COUNTY GALWAY Martin Fitzpatrick M.A. Through Time Ltd. Professional Archaeological Services Old church Street, Athenry, Co. Galway www.throughtimeltd.com 2 Archaeological & Cultural Heritage Assessment of route options in Dunmore, County Galway. COPIES OF THIS ARCHAEOLOGICAL REPORT HAVE BEEN PRESENTED TO: Client: O’Connor Sutton Cronin Consulting Engineers on behalf of Galway County Council. Statutory Bodies: National Monuments Service, Dept. of Culture, Heritage and Gaeltacht. The National Museum of Ireland. Galway County Council. PLEASE NOTE… Any recommendations contained in this report are subject to the ratification of the National Monuments Service, Department of Culture, Heritage and The Gaeltacht. COPYRIGHT NOTE Please note that the entirety of this report, including any original drawings and photographs, remain the property of THROUGH TIME LTD. Any reproduction of the said report thus requires the written permission of THROUGH TIME LTD. 3 Archaeological & Cultural Heritage Assessment of route options in Dunmore, County Galway. Disclaimer The results, conclusions and recommendations contained within this report are based on information available at the time of its preparation. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that all relevant data has been collated, the authors and Through Time Ltd. accept no responsibility for omissions and/or inconsistencies that may result from information becoming available subsequent to the report’s completion.