The Lewis Carroll Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Granat Family History

The Granat Family History by Virginia Mapes March 17, 2012 Sweden The number of Swedes doubled between 1750 and 1850, and the growth continued. In a country with few industries and cities, the burden had to be carried by the primitive agricultural society. At the end of the 1860s, Sweden was struck by the last of a series of severe hunger catastrophes. The agriculture which was still only partially modernized had been struggling with difficult times. Now came a series of crop failures. 1867 thus became "the wet year" of rotting grain, 1868 became the "dry year" of burned fields, and 1869 became "the severe year" of epidemics and begging children. Sixty thousand people left Sweden during these three "starvation years." It was the beginning of the mass emigration which, with short intervals, was to continue up to World War I. (Written by Ulf Beijbom) John Richard Karlsson Per (John) Richard Karlsson was born May 24, 1882 in Hova, Sweden to Karl Karlsson and Lovisa Johansdotter. [Richard’s last name was changed from Karlsson to Granat when he was in the Swedish Military Service in 1905.] Richard recalled walking the trails to school. However when winter came and the snow was deep, he would ski to school. It was so much faster because he could ski over the tops of the fences creating a shorter route. Richard’s childhood years in Sweden are somewhat vague. He had a sister Ellen and there may have been other brothers and sisters. They were a very poor farm family. Richard remembered that he and the other children in the family were always hungry, for these were the starvation years for the farm workers. -

PDF Download Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense: Collected Poems

JABBERWOCKY AND OTHER NONSENSE: COLLECTED POEMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lewis Carroll | 464 pages | 31 Oct 2012 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141195940 | English | London, United Kingdom Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense: Collected Poems PDF Book It made a lot more sense reading it with the pictures acting it out, because most of the time, I had no idea what Carroll was saying with those crazy made up words. I won a prize and my poem was selected as the best out of all the primary schools in my home town. Added to basket. Hardback edition. The poems range from those written for friends and family, little girls he fancied, Oxford rhymes critiquing his university's politics some things never change , extracts from Wonderland, 'Phantasmagoria', 'The Hunting of the Snark', 'Sylvia and Bruno', and various miscellaneous. The poems are set out chronologically following a generous, thoughtful introduction from the esteemed Cambridge critic Gillian Beer. This edition is the first compiled collection of his poems, including both prominent and lesser known verses. Call us on or send us an email at. Read it Forward Read it first. Shelves: lawsonland , reread , poetry. I didn't really enjoy this collection. Grand Union. More filters. I feel if you can open a book at any page and read a random poem you would enjoy this book more. Hardback All in the golden afternoon Full leisurely we glide There is so much to love an We are building little homes on the sands And time does indeed flit away, burbling and chortling. The humor, sparkling wit and genius of this Victorian Englishman have lasted for more than a century. -

Style Specifications

Site Soundscapes Landscape architecture in the light of sound Per Hedfors Department of Landscape Planning Ultuna Uppsala Doctoral thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala 2003 Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae Agraria 407 ISSN 1401-6249 ISBN 91-576-6425-0 © 2003 Per Hedfors, Uppsala Tryck: SLU Service/Repro, Uppsala 2003 Abstract Hedfors, Per. 2003. Site Soundscapes – landscape architecture in the light of sound. Doctor’s dissertation. issn 1401-6249, isbn 91-576-6425-0. This research was based on the assumption that landscape architects work on pro- jects in which the acoustic aspects can be taken into consideration. In such projects activities are located within the landscape and specific sounds belong to specific activities. This research raised the orchestration of the soundscape as a new area of concern in the field of landscape architecture; a new method of approaching the problem was suggested. Professionals can learn to recognise the auditory phenom- ena which are characteristic of a certain type of land use. Acoustic sources are obvious planning elements which can be used as a starting point in the develop- ment process. The effects on the soundscape can subsequently be evaluated according to various planning options. The landscape is viewed as a space for sound sources and listeners where the sounds are transferred and coloured, such that each site has a specific soundscape – a sonotope. This raised questions about the landscape’s acoustic characteristics with respect to the physical layout, space, material and furnishing. Questions related to the planning process, land use and conflicts of interest were also raised, in addition to design issues such as space requirements and aesthetic considerations. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

Download PDF Version of Issue 87

Cambridge Alumni Magazine Issue 87 — Easter 2019 A hitchhiker’s guide to Douglas Adams’s Cambridge Tax policy might not be sexy but it determines the character of society Why sport is good for students – and for their academic results EASTER 2019 | CAM 87 1 2 CAM 87 | EASTER 2019 Editor Mira Katbamna Managing editor Steve McGrath Design and art direction Rob Flanagan University of Cambridge Bruce Mortimer Charis Goodyear Cambridge Alumni Magazine Issue 87 Easter 2019 02 INBOX Publisher The University of Cambridge Development & Alumni Relations Campendium 1 Quayside, Bridge Street 20 Cambridge CB5 8AB Tel +44 (0)1223 332288 07 DON’S DIARY Dr JD Rhodes. Editorial enquiries Tel +44 (0)1223 332288 08 MY ROOM, YOUR ROOM [email protected] Josie Rourke (Murray Edwards 1995). 11 SOCIETY Alumni enquiries Tel +44 (0)1223 332288 Cambridge University Brass Band. [email protected] 13 BRAINWAVES alumni.cam.ac.uk facebook.com/cambridgealumni Professor Stephen J Toope. @Cambridge_Uni #camalumni Contents Advertising enquiries Features Tel +44 (0)20 7520 9474 [email protected] 14 WHY TAX IS GOOD FOR YOU Services offered by advertisers Tax policy might not be sexy but it is at are not specifically endorsed the heart of determining the character by the editor, YBM Limited of a society. CAM investigates. or the University of Cambridge. The publisher reserves the right to 20 COMPLEXITY. BEAUTY. MYSTERY. decline or withdraw advertisements. Dr Ross Waller says that we know very Cover little about single-celled organisms. Illustration: Holly Exley. 24 DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is Whether it’s a response to the digital published by Penguin Random House. -

The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, the Hunting of the Snark, a Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online

yaTOs (Download pdf) The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online [yaTOs.ebook] The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Pdf Free Lewis Carroll ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1419651 in Books 2011-11-07Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 1.70 x 6.50 x 9.30l, 1.70 #File Name: 0890097003440 pages | File size: 46.Mb Lewis Carroll : The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Wonderful books for a wonderful priceBy llamapyrLewis Carroll must've been the greatest children's book author of his time. I really admire his writing style and the creativity of his books, having grown up on them since I was 6. I've got a bunch of his novels in hardcover and paperback sitting on my shelves, so it seemed only right to add some digital versions to my library :)Anyway, I came here looking for Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and found this set, and for a mere 99 cents it seemed worth a look. -

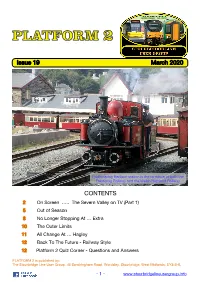

Platform 2 Quiz Corner - Questions and Answers

Issue 19 March 2020 Porthmadog Harbour station is the terminus of both the Ffestiniog Railway and the Welsh Highland Railway CONTENTS 2 On Screen ….. The Severn Valley on TV (Part 1) 5 Out of Season 8 No Longer Stopping At … Extra 10 The Outer Limits 11 All Change At … Hagley 12 Back To The Future - Railway Style 12 Platform 2 Quiz Corner - Questions and Answers PLATFORM 2 is published by: The Stourbridge Line User Group, 46 Sandringham Road, Wordsley, Stourbridge, West Midlands, DY8 5HL - 1 - www.stourbridgelineusergroup.info ON SCREEN … THE STOURBRIDGE MAIN LINE AND BRANCHES 3. THE SEVERN VALLEY ON TV - 1972-1993 by John Warren This is the third article in a series that looks at the occasions when the Stourbridge line or its branch lines have featured either in feature films or in television series. The Severn Valley Railway had only been open for two years and only operated between Bridgnorth and Hampton Loade when it was first discovered by the television industry as a location for a television sequence. The programme was Doctor In Charge, the third incarnation of the “Doctor” series of comedies based on the books of Richard Gordon, and was broadcast between 1972 and 1973. It had been preceded by Doctor In The House and Doctor At Large, and later series included Doctor At Sea and Doctor On The Go. The episodes were written by Graeme Garden and Bill Oddie post I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again and before The Goodies and starred Robin Nedwell, Richard O’Sullivan, George Layton, Geoffrey Davies and Ernest Clark. -

Phantasmagoria and Other Poems, by Charles Dodgson, AKA Lewis Carroll

www.freeclassicebooks.com Phantasmagoria and Other Poems, By Charles Dodgson, AKA Lewis Carroll www.freeclassicebooks.com 1 www.freeclassicebooks.com Contents PHANTASMAGORIA.................................................................................................................................3 CANTO I‐‐The Trystyng........................................................................................................................3 CANTO II‐‐Hys Fyve Rules....................................................................................................................6 CANTO III‐‐Scarmoges.........................................................................................................................8 CANTO IV‐‐Hys Nouryture.................................................................................................................11 CANTO V‐‐Byckerment......................................................................................................................14 CANTO VI‐‐Dyscomfyture..................................................................................................................17 CANTO VII‐‐Sad Souvenaunce...........................................................................................................20 ECHOES .................................................................................................................................................22 A SEA DIRGE ..........................................................................................................................................23 -

MONTY PYTHON at 50 , a Month-Long Season Celebra

Tuesday 16 July 2019, London. The BFI today announces full details of IT’S… MONTY PYTHON AT 50, a month-long season celebrating Monty Python – their roots, influences and subsequent work both as a group, and as individuals. The season, which takes place from 1 September – 1 October at BFI Southbank, forms part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of the beloved comedy group, whose seminal series Monty Python’s Flying Circus first aired on 5th October 1969. The season will include all the Monty Python feature films; oddities and unseen curios from the depths of the BFI National Archive and from Michael Palin’s personal collection of super 8mm films; back-to-back screenings of the entire series of Monty Python’s Flying Circus in a unique big-screen outing; and screenings of post-Python TV (Fawlty Towers, Out of the Trees, Ripping Yarns) and films (Jabberwocky, A Fish Called Wanda, Time Bandits, Wind in the Willows and more). There will also be rare screenings of pre-Python shows At Last the 1948 Show and Do Not Adjust Your Set, both of which will be released on BFI DVD on Monday 16 September, and a free exhibition of Python-related material from the BFI National Archive and The Monty Python Archive, and a Python takeover in the BFI Shop. Reflecting on the legacy and approaching celebrations, the Pythons commented: “Python has survived because we live in an increasingly Pythonesque world. Extreme silliness seems more relevant now than it ever was.” IT’S… MONTY PYTHON AT 50 programmers Justin Johnson and Dick Fiddy said: “We are delighted to share what is undoubtedly one of the most absurd seasons ever presented by the BFI, but even more delighted that it has been put together with help from the Pythons themselves and marked with their golden stamp of silliness. -

Carlson Magazine Fall 2019

CARLSON THECARLSONSCHOOL OFMANAGEMENT MAGAZINEFORALUMNI ANDFRIENDS SCHOOL 100 YEARS OF The CARLSON School Centennial Celebration Weekend The Carlson School celebrated its centennial September 13 and 14 with events at U.S. Bank Stadium and during Gopher Game Day at TCF Bank Stadium. Check out pages 54�55 and carlsonschool.umn.edu for more coverage of the weekend. UNIVERSITYOFMINNESOTA CONTENT INTHISISSUE STARTUPNEWSBRIEFS CARLSONSCHOOLPARTNERSHIPHELPSKEEP LAKESCLEAN PEOPLEQUESTIONS CREATINGAMERICA'S FIRSTMISDEPARTMENT ALUMNIWHOMADEHISTORY ENGAGEMENT&GIVING NEWS&NOTES ALUMNIHAPPENINGS CLASSNOTES THINGSI’VELEARNEDSHELLEYNOLDEN FEATURES FROMTHEDEAN FACESOFCARLSON GORDONDAVIS&THEHISTORYOFMIS ATTHECARLSONSCHOOL STUDENTSLEARNINGFROMEXPERIENCE EXECUTIVESPOTLIGHT WHYEVERYCARLSONSCHOOL JIMOWENSCEOH B FULLER UNDERGRADSTUDIESABROAD THEIMPORTANCEOFGLOBALLEARNING FALL |CARLSONSCHOOLOFMANAGEMENT THECARLSONSCHOOL Asia Centennial Forum OFMANAGEMENT More than 150 alumni gathered in Shanghai for the Asia Centennial Forum in June. MAGAZINEFOR This exciting two-day event featured world-renowned Carlson School faculty, Asian ALUMNIANDFRIENDS business leaders, and alumni thought leaders discussing some of the most pressing business issues of the day. The event concluded with a Saturday evening gala. MAGAZINEEDITORS James Plesser Andre Eggert MAGAZINEDESIGN Daniele Lanza Nick Khow CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Taylor Hugo, Wade Rupard, Patrick Stephenson, Kate Westlund CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Hannah Pietrick, Jeff Thompson ©2019 by the Regents of -

Hvem Er Douglas Adams

Kopi fra DBC Webarkiv Kopi af: Kenneth Bernholm : Hvem er Douglas Adams Dette materiale er lagret i henhold til aftale mellem DBC og udgiveren. www.dbc.dk e-mail: [email protected] Hvem er Douglas Adams Kenneth Bernholm Published: 2005 Tag(s): biografi 1 Forfatter: Kenneth Bernholm (http://kennethbernholm.dk) Licens: Creative Commons Navngivelse-Ikke-kommerciel-Ingen bearbe- jdelser 2.5 Danmark License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-nd/2.5/dk/) ISBN: 978-87-91845-14-7 2 Chapter 1 Historien om Douglas Adams er i høj grad historien om hans forfatter- skab. Skæbnen, hvis man tror på den slags, ville nemlig, at Douglas Adams var på rette tid og sted med den rette historie. Tiden var 1978, stedet var den britiske radio BBC og historien var The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Før denne tid havde Douglas uden synderlig succes kæmpet for at ernære sig som forfatter, men efter hans humoristiske science-fiction radiohørespil blev sendt på BBC, blev han et kultikon og hans bøger bestsellere. Man kan dårligt fortælle om personen og for- fatteren Douglas Adams uden samtidig at fortælle historien om Hånd- bog for vakse Galakse-Blaffere, som bogen kom til at hedde på dansk. Den skæbne, der tildelte ham livets store success, formåede desværre også at tage sig godt betalt. Douglas Adams døde den 11. maj 2001 i et fitnesscenter i Californien, hvor et hjerteanfald slukkede hans livslys. Han var næsten to meter høj, men blev kun 49 år gammel og efterlod sig ikke kun et populært forfatterskab og en kone og datter, men også en ab- surd verden, der altid blev en hel del klarere, når den blev betragtet og kommenteret af Douglas. -

Picture As Pdf

1 Cultural Daily Independent Voices, New Perspectives A Grand Disarray in the Gardens Sylvie Drake · Wednesday, July 20th, 2016 There is a morbid fascination with lives lost or thrown away, the puzzlement of people sinking into hoarding, the zoning out, the giving up and giving in to squalor. Who would have thought that you could make a musical based on such a premise, let alone a pretty compelling one? Apparently, Doug Wright (author of I Am My Own Wife), Scott Frankel (music) and Michael Korie (lyrics) did. And we’re glad they did, as the musical born of that attempt — Grey Gardens, now at the Ahmanson Theatre — proves again that musical theatre can rise to surprising heights tackling just about any subject, no matter how dark or unlikely. Think of Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd and think especially of the Tom Kitt/Brian Yorkey Next to Normal, which so movingly chronicles the devastation of one woman’s bipolar disorder to the confusion and bewilderment of her family. Grey Gardens is largely based on the Maysles Brothers 1975 documentary about Edith Bouvier Beale and her daughter, “Little Edie” Beale, relatives of Jackie Bouvier Kennedy Onassis and once members of the same East Coast aristocracy. Thanks to a kind of reckless irrationality, the women over time sank into poverty and grime at the once grand 28-room mansion they shared in The Hamptons. The documentary made a large impression, not least because of the family name, but also because it was unsparing in its tell-all detail, showing us how these two not untalented women also shared a profound disconnection with reality and a stifling co- dependent relationship with each other.