Bjarke Ingels on His Revolutionary Architecture: We're Here to Push the Boundaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Data

Supplemental data Appendix A. Teams and companies involved in the competition •Designteam AIM (Helsingborg) and Onix Sweden AB (Helsingborg) with advisors/consultants Noema Culture & Place Mapping (London), Atkins (Malmö) and Farawaysoclose/Apokalyps Labotek (Malmö) • Bjarke Ingels Group (Copenhagen), Spacescape (Stockholm), Testbedstudio (Stockholm), Topotek 1& Man Made Land (Berlin) and Resource Vision (Stockholm) • BSK Arkitekter AB (Stockholm), MVRDV (Rotterdam) and Grontmij in Sweden AB (Stockholm) • COBE Aps (Copenhagen) with advisors Kragh & Berglund (Copenhagen and Stockholm), Moe & Brödsgård (Rödovre), Yngve Andrén Konsult AB (Stockholm) and Boris Broman Jensen (Århus) • Ecosistema Urbana (Madrid), Arkitekt Kristine Jensens Tegnestue (Århus), 700N arkitektur AS (Tromsö), Ljusarkitektur (Stockholm) and Atkins (Stockholm) • KCAP Architect & Planners (Rotterdam) and CaseStudio (Göteborg) • Norconsult Byplan (Sandvika), Norconsult landskapsarkitekt (Sandvika), Fantastic Norway (Oslo) and 0047 International AS (Oslo) • Tham och Videgård Arkitekter (Stockholm), Territorial Agency (London) and a_zero environmental architects (London) • Tovatt Architects & Planners (Stockholm), Atelier Dreiseitl (Űeberlingen), Urban Think Tank Architects LLC (Zürich) and Wenanders (Stockholm) • White arkitekter AB (Stockholm), Ghilardi + Hellsten (Oslo), Spacescape (Stockholm), Vectura Consulting AB (Solna) and Evidens BLW AB (Stockholm) Appendix B. Questions asked in the questionnaire used in this study Please select the one answer that best applies. -

16-0530 SARA NY Awards 2016 Final

2 SARA| NY DESIGN AWARDS0 11 6 CTA ARCHITECTS P.C. WWW.CTAARCHITECTS.COM ARCHITECT HELPING ARCHITECT SINCE 1956 CONGRATULATIONS TO THE 2016 SARA NY DESIGN AWARDS WINNERS TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS SARA|NY thanks the following people for making the 2016 Design Awards Program a great success: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 05 Our deepest appreciation goes to SARA|NY President T amar Kisilevitz , ARA and Vice President Frank A. Szatkowski , ARA for their leadership and support throughout this year’s success. ABOUT SARA 06 To 2016 Special Design Awards Committee Co-Chairs Tim Maldonado , FARA and Ken Conzelmann , ARA, who led this year’s SARA|NY Special Awards s election and arranged MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT 08 project tours. For providing us with informative building tours in consideration for the 2016 SARA|NY Special MESSAGE FROM THE VICE-PRESIDENT 09 Awards: • Saint Ann’s Warehouse: Zachary Griffin, RA , Associate, Marvel Architects; Elizabeth Candela , Development and Marketing, Marvel Architects; Jonathan J. Marvel , FAIA, Founding 2016 SARA|NY SPECIAL AWARD: VIA 57 WEST 10 Partner, Marvel Architects; Lissa So , Founding Partner, Marvel Architects Bjarke Ingels Group • 551W21: Jeremy Dworken , Associate, Foster + Partners; Nelson Estrada , Engineer, Triton Construction; Norman Foster , Chairman and Founder, Foster + Partners; James Barnes , Partner, Foster + Partners; Peter Han , Partner, Foster + Partners 2016 SARA|NY SPECIAL AWARD: TWA FLIGHT CENTER 16 • Via 57 West: Beat Schenk , Project Leader, Bjarke Ingels Group; Alessandro Ronfini , Beyer Blinder Belle Designer, Enclos; Bjarke Ingels , Founding Partner, Bjarke Ingels Group • TWA Flight Center: Richard W. Southwick , FAIA, Partner, Director of Historic Preservation, 2016 SARA|NY DESIGN AWARDS OF EXCELLENCE 23 Beyer, Blinder, Belle; Tyler Morse , CEO, Managing Partner, MCR Development LLC We would like to thank Design Awards Committee Co-Chairs Tamar Kisilevitz and Asaf 2016 SARA|NY DESIGN AWARDS OF HONOR 33 Yogev for their many contributions to the success of the Design Awards Program. -

The Durst Organization Commissions Stephen Glassman to Create Grand-Scale Artwork to Complement New Bjarke Ingels Group Mixed-Use Residence, VIA 57 West

The Durst Organization Commissions Stephen Glassman to Create Grand-Scale Artwork to complement new Bjarke Ingels Group Mixed-Use Residence, VIA 57 West Inspired by the Adjacent Hudson River, Flows Two Ways Sculpture Connects the Built and Natural Environments Los Angeles, CA – February 9, 2016 - Stephen Glassman Studio (SGStudio) today announced a commission from The Durst Organization (TDO) for a monumental outdoor sculpture for Manhattan’s new “superblock” development, 57 West, located at West 57th Street between 11th and 12th Avenues. Flows Two Ways (2016) is TDO’s first site-specific commission, and continues the organization’s enduring support of the arts. Scaling eight stories at sixty-by-sixty feet, the work will denote the main entrance to VIA 57 WEST, the torqued tetrahedral residential and mixed-use “courtscraper” that marks Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG)’s first project in the Americas. Installation will begin in March 2016 in anticipation of VIA’s spring opening. The work is named after a loose translation of the Hudson River’s Native American name, Muh-he-kun-ne-tuk – “the river that flows both ways” and serves as a metaphor for two forces that are separate yet connected: the river and the city. Flows Two Ways marks Glassman’s first permanent large-scale New York work. “The history of sculpture and skyscraper in New York City is unique and powerful, and I’m honored to be working with the Dursts and BIG on this project,” said artist Stephen Glassman. “As a New York native, the movement to save the Hudson River was formative in my growth as an artist intent on creating works of scale and social impact. -

Bjarke Ingels Group WEWORK SCHOOL, NEW YORK, USA

Gople Bjarke Ingels Group WEWORK SCHOOL, NEW YORK, USA Architectural Project: WeWork & BIG Photo: Dave Burk 3 GOPLE LAMP 4 BJARKE INGELS GROUP BJARKE INGELS GROUP BIG is a group of architects, designers and thinkers operating within innovative as they are cost and resource conscious, incorporating the fields of architecture, urbanism, research and development with overlapping design disciplines for a new paradigm in architecture. offices in Copenhagen and New York City. BIG has created a reputation BIG believe strongly in research as a design tool. for completing buildings that are as programmatically and technically 5 GOPLE LAMP 6 DESIGNERS MURANO GLASS A powerful LED light source is housed within a handblown glass diffuser, produced according to ancient Venetian glass-blowing techniques and created in Murano. The soft glass helps diffuse a soft glow, as light fills the pill shaped diffuser. The diffuser is available in three options: crystal glass with a white gradient, transparent glass with a silver or copper metallic finish. 7 GOPLE LAMP 8 BJARKE INGELS GROUP THE HUMAN LIGHT Gople Lamp is the perfect example of Artemide’s guiding philosophy of “The Human Light”. It aspires to create light that is good for the wellness of man and for the environment that has a positive impact on our quality of life. 9 GOPLE LAMP 10 BJARKE INGELS GROUP SAVOIR FAIRE The human and responsible light goes hand in hand with design and material savoir faire, combining next-generation technology with ancient techniques. It is a perfect expression of sustainable design. BIG OFFICES, COPENHAGEN, DENMARK Architectural Project: Offices 11 GOPLE LAMP 12 BJARKE INGELS GROUP WELLNESS The end result is a product that delivers both visual comfort and aesthetic value, while contributing to the wellness of both man and the environment. -

Table of Contents

CITYFEBRUARY 2013 center forLAND new york city law VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1 Table of Contents CITYLAND Top ten stories of 2012 . 1 CITY COUNCIL East Village/LES HD approved . 3 CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CPC’s 75th anniversary . 4 Durst W . 57th street project . 5 Queens rezoning faces opposition . .6 LANDMARKSFPO Rainbow Room renovation . 7 Gage & Tollner change denied . 9 Bed-Stuy HD proposed . 10 SI Harrison Street HD heard . 11 Plans for SoHo vacant lot . 12 Special permits for legitimate physical culture or health establishments are debated in CityLand’s guest commentary by Howard Goldman and Eugene Travers. See page 8 . Credit: SXC . HISTORIC DISTRICTS COUNCIL CITYLAND public school is built on site. HDC’s 2013 Six to Celebrate . 13 2. Landmarking of Brincker- hoff Cemetery Proceeds to Coun- COURT DECISIONS Top Ten Stories Union Square restaurant halted . 14. cil Vote Despite Owner’s Opposi- New York City tion – Owner of the vacant former BOARD OF STANDARDS & APPEALS Top Ten Stories of 2012 cemetery site claimed she pur- Harlem mixed-use OK’d . 15 chased the lot to build a home for Welcome to CityLand’s first annual herself, not knowing of the prop- top ten stories of the year! We’ve se- CITYLAND COMMENTARY erty’s history, and was not compe- lected the most popular and inter- Ross Sandler . .2 tently represented throughout the esting stories in NYC land use news landmarking process. from our very first year as an online- GUEST COMMENTARY 3. City Council Rejects Sale only publication. We’ve been re- Howard Goldman and of City Property in Hopes for an Eugene Travers . -

Cv Grima Eng 2016 Full

Joseph Grima Born 24 February 1977, Avignon (France) Nationality: British Current address: Piazza de Marini 4 16123 Genova (GE) Italy Email: [email protected] Twitter: @joseph_grima Instagram: @josephgrima Education 2001 - 2003 Diploma in Architecture Architectural Association School of Architecture (London, UK) 1997 - 2000 BA in Architecture (1st class honours) Oxford Brookes University (Oxford, UK) Current titles and positions 2014 - ongoing Founder and principal Space Caviar (architecture, design and research studio, Genoa, Italy) (www.spacecaviar.net) 2015 - ongoing Director IdeasCity Program and conference cycle at the New Museum, New York (www.ideas-city.org) 2015 - ongoing Artistic Director Matera Italy), European Capital of Culture 2019 Previous affiliations 2010 – 2013 Editor in Chief Domus magazine (Milan, Italy) - international bilingual architecture and design review founded by Gio Ponti in 1928, distributed in 88 countries 2007 – 2010 Director Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York (USA) 2003 – 2007 Editor Domus magazine, Milan (Italy) Teaching 2015 - ongoing Unit Master (advanced architecture studio) Architectural Association School of Architecture, London 2016 - ongoing Sir Banister Fletcher Visiting Professor Bartlett, University College, London 2014-15 Visiting Professor Department of Architecture, University of Genova, Italy 2011-13 Studio Master Strelka Institute of Media, Arts and Design, Moscow (w/ Jiang Jun) Fabrica, Treviso, Italy 2010-12 Visiting Lecturer Domus Academy, Milan and Eindhoven Design Academy, -

Mountain Dwellings: Category Winner of World Architecture Festival 2008

Mountain Dwellings: Category Winner of World Architecture Festival 2008 Looking at the splendid photos of this building, what would you imagine? Is it a public building or a residential building? Or else? Named as Mountain Dwellings, this building is located in the Orestad, 33.000 m2, a new urban development in Copenhagen, Denmark. It contains housing (1/3)and parking (2/3) in combining successfully the splendours of the suburban backyard with the social intensity of urban density. Its visual appearance is stunning. The nice architecture design and success construction have enabled it to be the Category Winner of World Architecture Festival 2008 (http://www.worldbuildingsdirectory.com/project.cfm?id=755). What makes this project comfortable for living is that the parking area is connected to the street, and all apartments have roof gardens facing the sun, amazing views and parking on the 10th floor. The Mountain Dwellings appear as a suburban neighbourhood of garden homes, floating over a 10-storey building - suburban living with urban density. The residents of the 80 apartments will be the first in Orestaden to have the possibility of parking directly outside their homes. The gigantic parking area contains 480 parking spots and a sloping elevator that moves along the mountain’s inner walls. In some places the ceiling height is up to 16 meters which gives the impression of a cathedral-like space. The color design from facade to floor during the day and during the night makes the building unique from architectural point of view. Sika contributed in the decorative colour design of Mountain Dwellings. -

First Generation Second Generation

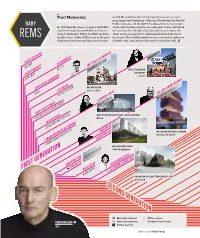

by Paul Makovsky world. Not only has the firm designed some of our era’s most important buildings—Maison à Bordeaux, the Seattle BABY Public Library, and the CCTV headquarters, to name just In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia a few—but its famous hothouse atmosphere has cultivated and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon VriesenVriesen-- the talents of hundreds of gifted architects. Look at the dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan chart on these pages: it is a distinguished architectural REMS Architecture. Today OMA is one of the most fraternity. These OMA grads have now created an influence influential architectural practices in the all their own, and they are the ones to watch in 2011. P ZAHA HADID RIENTS DIJKSTRA EDZO BINDELS MAXWAN MATTHIAS SAUERBRUCH WEST 8 SAUERBRUCH HUTTON EVELYN GRACE ACADEMY CHRISTIAN RAPP London RAPP + RAPP CHRISTOPHE CORNUBERT M9 MUSEUM LUC REUSE Venice, Italy WILLEM JAN NEUTELINGS PUSH EVR ARCHITECTEN NEUTELINGS RIEDIJK LAURINDA SPEAR ARQUITECTONICA KEES CHRISTIAANSE SOUTH DADE CULTURAL ARTS CENTER KGAP ARCHITECTS AND PLANNERS Miami YUSHI UEHARA ZERODEGREE ARCHITECTURE MVRDV WINY MAAS MUSEUM AAN DE STROOM Antwerp, Belgium RUURD ROORDA KLAAS KINGMA JACOB VAN RIJS KINGMA ROORDA ARCHITECTEN BALANCING BARN Suffolk, England FOA WW ARCHITECTURE SARAH WHITING FARSHID MOUSSAVI RON WITTE FIRST GENERATION MIKE GUYER ALEJANDRO ZAERA POLO GIGON GUYER MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART Cleveland SECOND GENERATION Married/partnered Office closed REM KOOLHAAS P Divorced/separated P Pritzker Prize laureate OMA Former partner Illustration by Nikki Chung REM_Baby REMS_01_11_rev.indd 1 12/16/10 7:27:54 AM BABY REMS by Paul Makovsky In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesen- dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture. -

Generali Real Estate and Citylife Presented the New Project

The new gateway to CityLife Air, light, greenery and open spaces: a project designed for people and the city The global studio BIG-BJARKE INGELS GROUP has designed the new project Milan, 15 November 2019 - CityLife today presented the new project that marks the start of the district completion phase and that will create a new gateway to CityLife and the city. Selected following an international competition between major design and architectural studios, the project was created by the studio BIG - Bjarke Ingels Group. The project envisages the creation of two buildings joined by a roof with an urban-scale portico that, framing the three existing towers without reaching their height, will create a new gateway to CityLife from Largo Domodossola through an extensive green area that will further enrich the liveability of the district and constitute a new aspect of restoration for the City of Milan. A project designed for people that creates a bridge between private and public spaces. The roof will not only be an element forming a structural connection between the two buildings, but will also create a shaded public realm activated by street furniture and green spaces that can be used year-round. The architectural intervention was designed to open up and fully integrate the district, starting from the existing space and context. The new CityLife gateway will be integrated with the urban areas, the streets and the existing road network, creating a continuum between the district and the city. The new building will stand on an area of around 53,000 square metres (GFA) more than 200 metres long, with a characteristic portico structure that will be 18 metres wide at its narrowest point. -

Sehr Geehrte Damen Und Herren

BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON IHA 2016 - ARCHITECT Frankfurt/Main, November 2, 2016 BIG Bjarke Ingels Group Architect of “VIA 57 West” – winner of the International Highrise Award 2016 Office profile: BIG is a Copenhagen and New York based group of architects, designers, builders, and thinkers operating within the fields of architecture, urbanism, interior design, landscape design, product design, research and development. The office is currently involved in a large number of projects throughout Europe, North America, Asia and the Middle East. BIG's architecture emerges out of a careful analysis of how contemporary life constantly evolves and changes. BIG believes that in order to deal with today's challenges, architecture can profitably move into a field that has been largely unexplored. A pragmatic utopian architecture that steers clear of the petrifying pragmatism of boring boxes and the naïve utopian ideas of digital formalism. Like a form of programmatic alchemy they create architecture by mixing conventional ingredients such as living, leisure, working, parking and shopping. By hitting the fertile overlap between pragmatic and utopia, the architects once again find the freedom to change the surface of our planet, to better fit contemporary life forms. Bjarke Ingels started BIG Bjarke Ingels Group in 2005 after co-founding PLOT Architects in 2001 and working at OMA in Rotterdam. Through a series of award- winning design projects and buildings, Bjarke has developed a reputation for designing buildings that are as programmatically and technically innovative as they are cost and resource conscious. Bjarke has received numerous awards and honors, including Wall Street Journal's Innovator of the Year Award, the Danish Crown Prince's Culture Prize in 2011, the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2004, and the ULI Award for Excellence in 2009. -

COP-GLOBAL COMPACT BIG - Bjarke Ingels Group OUR COMMITMENT

COP-GLOBAL COMPACT BIG - Bjarke InGels Group OUR COMMITMENT This Communication on progress breaks the standard in that our communicating to you is our assurance that we continue to support the Global Compact principles on corporate social responsibility. Corporate social responsibility – to some, just modern buzz words. But, at BIG, it a way of doing business. It is BIG’s way of doing business, across the business and we, the 8 partners, are pleased to place our signatures herewith to assure Global Compact that we are committed to the continuous respect for the human race and its environment. as our reach becomes increasingly international, we have the ears of more individuals, government leaders and industry colleagues. our ideas spread and new collaborations become possible. More ideas are shared across companies, allowing for increased idea development, as it is the lack of innovation which impedes achieving solutions. Global Compact is BIG’s stamp of integrity on sustainability and innovation. We choose to contribute. Bjarke Ingels, Founding partner Sheela Maini søgaard, CEO, associate partner David Zahle, partner, recruitment Finn nørkjær, partner Jakob lange, partner Thomas Christoffersen, partner Andreas klok pedersen, partner Kai-uwe Bergmann, associate partner OUR INTRODUCTION architecture is never triggered by a single event, never conceived by a single mind, and never shaped by a single hand. neither is it the direct materialization of a personal agenda or pure ideals, but rather the result of an ongoing adaptation to the multiple conflicting forces flowing through society. We architects don’t control the city – we can only aspire to intervene. architecture evolves from the collision of political, economical, functional, logistical, cultural, structural, environmental and social interests, as well as interest yet unnamed and unforeseen. -

A Decision on the Tender for the Masterplan of the Porta Romana Railway Yard Is Forthcoming

A DECISION ON THE TENDER FOR THE MASTERPLAN OF THE PORTA ROMANA RAILWAY YARD IS FORTHCOMING On Wednesday 31 March, the winner will be announced and the Public Consultation will begin Milan, Monday 22 March 2021 - The international tender procedure for the regeneration of the Porta Romana Railway Yard in Milan, announced by the Porta Romana Fund, in association with the COIMA ESG City Impact Fund, Covivio and Prada Holding S.p.A, is in its final stages. This 31 March will see the announcement of the winning Masterplan, selected from one of the six finalist teams: • BIG - Bjarke Ingels Group, Buro Happold, Atelier Ten, MIC - Mobility in Chain, Atelier Verticale, Ubistudio, SCE Project • Cobe A/S, SD Partners S.R.L., TRM Group S.R.L., AKT II, Hilson Moran, Urban Foresight • John McAslan + Partners, Meinhardt, Barker Langham, Makower Architects, Urbn’ita, MVVA, ESA Engineering • OUTCOMIST, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, PLP Architecture, Carlo Ratti Associati, Gross. Max, Nigel Dunnett Studio, Arup, Portland Design, Systematica, Studio Zoppini, Aecom, Land, Artelia • Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (Europe) LLP – SOM, Michel Desvigne Paysagiste (MDP), TSPOON, Work in Progress srl. (WiP), Drees & Sommer (DRESO), Elisabetta Lazzaro, United Consulting srl • Studio Paola Viganò, Inside Outside, OFFICE KGDVS, Piovenefabi, Ambiente Italia, F&M Ingegneria, TPS PRO, Antonella Faggiani - Smart Land Srl The press conference for the announcement will be open to all citizens, who can watch it at www.scaloportaromana.com The date will also mark the launch of the Public Consultation - as per the Program Agreement on Railway Stations in Milan - for the purpose of collecting the city’s observations and concerns on the Masterplan that wins the tender.