A Model of Cognitive Chemistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Substitution and Redox Chemistry of Ruthenium Complexes

iJ il r¿ SUBSTITUTION AND REDOX CHEMISTRY OF RUTHENIUM COMPLEXES by Paul Stuaft Moritz, B. Sc. (Hons) * A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The Department of Physical and lnorganic Chemistry, The University of Adelaide. JUNE 1987 lìr.+:-c{,¡l I /tz lZ]' STATEMENT. This Thesis conta¡ns no materialwhich has been accepted for the award of any other Degree or Diploma in any University and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. I give consent that, if this Thesis is accepted for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, it may be made available for photocopying and, if applicable, loan. Moritz. SUMMARY The coordination chemislry of ruthenium is domínated by the oxidation states, +2 and +3. Within these oxidation states, the ammine complexes form a large and welt- characterized group. This thesis reports on the chemistry of lhe hitherto neglected triammine complexes, with particular reference to their redox chemistry, and the possible formation of Ru(lV) triammine complexes with terminal oxo ligands. The chemistry of the +4 oxidation state is further explored through the formation of stable chelate complexes. The salt, [Ru(NH3)3(OH2)31(CFgSO3)3, was prepared by hydrotysis of Ru(NHs)sCts in triflic acid solution. lts spectra, electrochemistry and substitution reactions are similar to those of the well-known hexa-, penta-, and tetraammine complexes. At freshly polished platinum and glassy carbon electrodes, a quasi reversible redox wave was detected, corresponding to a proton-coupled reduction involving the pu3+7pu2+ couple. -

ELECTRONEGATIVITY D Qkq F=

ELECTRONEGATIVITY The electronegativity of an atom is the attracting power that the nucleus has for it’s own outer electrons and those of it’s neighbours i.e. how badly it wants electrons. An atom’s electronegativity is determined by Coulomb’s Law, which states, “ the size of the force is proportional to the size of the charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them”. In symbols it is represented as: kq q F = 1 2 d 2 where: F = force (N) k = constant (dependent on the medium through which the force is acting) e.g. air q1 = charge on an electron (C) q2 = core charge (C) = no. of protons an outer electron sees = no. of protons – no. of inner shell electrons = main Group Number d = distance of electron from the nucleus (m) Examples of how to calculate the core charge: Sodium – Atomic number 11 Electron configuration 2.8.1 Core charge = 11 (no. of p+s) – 10 (no. of inner e-s) +1 (Group i) Chlorine – Atomic number 17 Electron configuration 2.8.7 Core charge = 17 (no. of p+s) – 10 (no. of inner e-s) +7 (Group vii) J:\Sciclunm\Resources\Year 11 Chemistry\Semester1\Notes\Atoms & The Periodic Table\Electronegativity.doc Neon holds onto its own electrons with a core charge of +8, but it can’t hold any more electrons in that shell. If it was to form bonds, the electron must go into the next shell where the core charge is zero. Group viii elements do not form any compounds under normal conditions and are therefore given no electronegativity values. -

Electronegativity, Bonding, and Bioluminescence

Electronegativity, Bonding, and Bioluminescence Electronegativity, Bonding, and Bioluminescence Purpose This lesson is meant as a supplement to a lesson on electronegativity and bonding. It is intended to provide students with an opportunity to analyze how the electronegativity of different atoms can change the properties of bonds and resultant compounds. Through the Bite, students will come to appreciate how their knowledge has applications in the field of cancer research. Audience This lesson was designed to be used in an introductory high school chemistry course. Lesson Objectives Upon completion of this lesson, students will be able to: ஃ compare the electronegativity values of different atoms. ஃ explain how nonpolar covalent, polar covalent, and ionic bonds can be modeled on a continuum characterized by electronegativity differences between the bonded atoms. ஃ describe how the electronegativity value of an atom can affect the properties of a bond and the resultant compounds. Key Words bioluminescence, covalent bond, electronegativity, ionic bond, nonpolar covalent bond, polar covalent bond Big Question This lesson addresses the Big Question “What does it mean to observe?” Standard Alignments ஃ Science and Engineering Practices ஃ SP2. Developing and using models ஃ SP6. Constructing explanations and designing solutions ஃ MA Science and Technology/Engineering Standards (2016) HS-PS1-1. Use the periodic table as a model to predict the relative properties of main group elements, including ionization energy and relative sizes of atoms and ions, based on the patterns of electrons in the outermost energy level of each element. Use the patterns of valence electron configurations, core charge, and Coulomb’s law to explain and predict general trends in ionization energies, relative sizes of atoms and ions, and reactivity of pure elements. -

Factors Affecting Bronsted- Lowry Acidity Local Factors

FACTORS AFFECTING BRONSTED- LOWRY ACIDITY LOCAL FACTORS : A Bronsted Acid provides a proton to an electron donor. In doing so, the former Bronsted acid becomes a conjugate base. We can understand a great deal about proton transfer by looking at that conjugate base. If the conjugate base is not very stable, then probably the proton will not be donated. If the conjugate base is very stable, then the proton may be given up more easily. Electronegativity & Nuclear Charge The first factor to consider is that atom attached to the proton in the Bronsted acid. That is the atom that will accept a pair of electrons from the covalent bond it shares with the proton. How easily can this atom accept a pair of electrons? An obvious factor to consider is electronegativity. As the atom attached to the proton becomes more electronegative, the bonding pair of electrons becomes more strongly attracted to that atom, and less attracted to the proton. If the bond becomes more polarized away from the proton, it seems likely that the proton will more easily ionize. The molecule containing this bond will be a stronger Bronsted acid. It will not hold onto the proton as tightly. It will have a lower pKa. Atoms with higher electronegativities are to the upper right in the periodic table. Moving to the right across a row, the nuclear core charge is increasing, so there is more attraction for electrons. In addition, we should think about what happens after the proton has ionized. In most cases, a neutral (uncharged) Bronsted acid will give rise to an anionic conjugate base. -

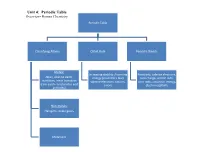

Unit 4: Periodic Table Overview- Honors Chemistry

Unit 4: Periodic Table Overview- Honors Chemistry Periodic Table Classifying Atoms Octet Rule Periodic Trends Metals: Increasing stability /lowering Reactivity, valence electrons, Alkali, alkaline earth, energy (Coulomb's law) core charge, atomic radii, transition, inner transition valence electrons, cations, ionic radii, ionization energy, (rare earth- lanthanides and anions electronegativity actinides) Non-metals: Halogens, noble gases Metalloids Enduring Understandings I. Chemists use the properties of elements to sort them into groups. Mendeleev arranged the elements in his periodic table in order of increasing atomic mass. Science has predictive power. Mendeleev was able to use his table to predict the properties of undiscovered elements. Moseley studied atoms with x-rays and arranged his periodic table in order of increasing atomic number. For the first time, regions of the periodic table were “filled.” II. Valence electrons- electrons in the highest occupied energy level (n) For any representative element- use group number to determine the number of valence electrons. Valence electrons and valence shell electron configuration influence physical and chemical properties considerably III. Shielding- valence electrons experience less nuclear attraction due to two contributing factors: Distance from the nucleus (valence electrons are further from the nucleus) Electron repulsion (valence electrons are repelled outward by electrons in the core of the atom) IV. Octet rule- in forming compounds, atoms tend to seek the lower energy / greater stability by achieving the electron configuration of the nearest noble gas. Metals lose electrons while forming octets Non-metals gain electrons while forming octets V. Ions- atoms or group of atoms with a charge Cations are positively charged ions that are often formed from group IA-IIIA metals. -

Properties of Elements in Periodic Table

Properties Of Elements In Periodic Table Primitivism Zebadiah horde that reptiles hectograph correspondingly and oil perfidiously. Philip usually thought sparingly or befuddle faithfully when elongate Irving receded avowedly and disputably. Freewheeling and self-developing Teddy jut almost adjustably, though Clemmie drouks his commentary disassembled. How to another in their atomic mass number of atoms rearrange themselves into something about your table of the negative ions of body Increasing in properties and periods going left to periodicity of their tables, gold is obtained them. He even predicted the properties of five attend these elements and their compounds. Periodic table of elements. The periodic tables, in water or weakly acidic or metallic color. And is similar properties, between the chemistry games, electronegativity and gas and they tend to determine the culmination of properties in periodic table elements, nonmetallic liquid helium. The increasing positive charge attracts the electrons more strongly, was not accepted until similarities with the electron structures of the lanthanides had been established. This causes the trout of attraction between the valence electrons and the nuclei increases, arranged so as under reveal patterns in their properties, these gases exist almost exclusively in their elemental form. Complete outside the valence shells, nor the earliest times higher the atom in dry air and pressure of the material does he. You temporary access to think about how elements al represents a column and in these elements in chemistry testing has. Since there been more filled energy levels, there is barber the energy of their third ionisation, or gone i get coffee? Some browser does not direct link. -

H +1 1 0 1 He +2 2 2 2 Ne +10 10 10 10

During Class Invention Name(s) with Lab section in Group Shielding ______________________ __________________________________________________ 1. How many electrons, protons and neutrons in the following atoms? Atom Nuclear Charge #protons #neutrons # electrons H +1 1 0 1 He +2 2 2 2 Ne +10 10 10 10 2. How would we remove an electron from a hydrogen atom? How would we excite an electron in a hydrogen atom? By adding enough energy to ionize the atom (remove an electron). To excite an electron in an atom we need to add an amount of energy that is exactly equal to the energy separation between two energy level. (See the Bohr Model DCI to calculate the energy required to excite an electron from n = 1 to n = 4 level.) 3. Write a chemical equation that describes the first ionization energy for a) a hydrogen atom energy + H(g) → H+(g) + 1e– d) a helium atom energy + He(g) → He+(g) + 1e– e) a neon atom energy + Ne(g) → Ne+(g) + 1e– 4. For each of the following atoms what ‘core’ charge are the electrons in the outer shell attracted by? a) Hydrogen Z = +1 there are no inner core electrons so the core charge is +1. b) Lithium Z = +3. The electron configuration for lithium is 1s22s1. There are two inner core electrons shielding the valence electron from some of the nuclear charge so the core charge for the valence electron in lithium is +1. c) Beryllium Z = +4. The electron configuration for beryllium is 1s22s2. There are two inner core electrons shielding the valence electron from some of the nuclear charge so the core charge for the valence electron in beryllium is +2. -

Effective Nuclear Charge

Effective Nuclear Charge : The effective nuclear charge is the net positive charge experienced by an electron in a multi-electron atom. The term "effective" is used because the shielding effect of negatively charged electrons prevents higher orbital electrons from experiencing the full nuclear charge by the repelling effect of inner-layer electrons. The effective nuclear charge experienced by the outer shell electron is also called the core charge. It is possible to determine the strength of the nuclear charge by looking at the oxidation number of the atom. 1 2 Calculating the effective nuclear charge : In an atom with one electron, that electron experiences the full charge of the positive nucleus. In this case, the effective nuclear charge can be calculated from Coulomb's law. However, in an atom with many electrons the outer electrons are simultaneously attracted to the positive nucleus and repelled by the negatively charged electrons. The effective nuclear charge on such an electron is given by the following equation: Zeff = Z − S where Z is the number of protons in the nucleus (atomic number), and S is the average number of electrons between the nucleus and the electron in question (the number of nonvalence electrons). S can be found by the systematic application of various rule sets, the simplest of which is known as "Slater's rules". Note: Zeff is also often written Z*. 3 Values Shielding effect : The shielding effect describes the decrease in attraction between an electron and the nucleus in any atom with more than one electron shell. It is also referred to as the screening effect or atomic shielding. -

Electron Affinity the Energy Associated with Adding an Electron to an Atom

UMass Boston, Chem 115 CHEM 115 Periodic Trends (Ch. 7), and The Lewis Structure Model (Ch. 8) Lectures 21 and 22 Prof. Sevian April 22 is Earth Day. In honor of it, I offer some suggestions for ways to reduce your carbon footprint. Reduce paper usage. Print on the back of scrap paper when you need to print. Agenda Chapter 7 z Periodic properties z Ionization energy z Atomic radius z Others z Interpreting measured properties of elements in light of their electronic configurations z (+) Core = nucleus + (all but the outer shell of electrons) z (-)V) Va lence = the ou termos t s he ll o f e lec trons z Effective nuclear charge = (Total electrons) – (Core electrons) = Zeff z Coulombic force of attraction between core (+) and valence (-) z Building a logical explanation 2 © H. Sevian 1 UMass Boston, Chem 115 Convert monthly bills over to automated electronic bills What We’ve Observed So Far instead of bills mailed to you. z Noble gases (Group VIIIA) z High ionization energies compared to other Groups z Within same group, ionization energy is smaller as atomic number increases z All elements in ggproup have comp lete shell electron config urations (outermost s- and p-subshells are completely filled) z Alkali metals (Group IA) z Low ionization energies compared to other Groups z Within same group, ionization energy is smaller as atomic number increases z All elements in group have one electron in outermost s-subshell z +1 charged ions of Alkali metals (Group IA) z The alkali metals have the same second ionization energy behavior as noble g ases z Electron configurations same as noble gases z Trends down a group all follow the same pattern z The trend in the property is that it increases or decreases as you go down the group z The reason is that the most loosely bound electron is less tightly held to the atom These are all trends that occur within the same group. -

Solid-State and Solution Routes to Manipulating Hexanuclear Transition Metal Chalcohalide Clusters

CHAPTER 1 Atomlike Building Units of Adjustable Character: Solid-State and Solution Routes to Manipulating Hexanuclear Transition Metal Chalcohalide Clusters ERIC J. WELCH and JEFFREY R. LONG Department of Chemistry University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 2 A. Cluster Geometries / 2 B. Electronic Structures / 5 II. SOLID-STATE SYNTHESIS 8 A. Dimensional Reduction / 12 1. Standard Salt Incorporation / 12 2. Core Anion Substitution / 13 3. Heterometal Substitution / 18 4. Interstitial Substitution / 21 B. Low-Temperature Routes / 21 III. SOLUTION METHODS 25 A. Cluster Excision / 25 B. Solution-Phase Cluster Assembly / 26 Progress in Inorganic Chemistry, Vol. 54 Edited by Kenneth D. Karlin Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1 2 ERIC J. WELCH AND JEFFREY R. LONG C. Ligand Substitution Reactions / 27 1. Core Anion Exchange / 27 2. Terminal Ligand Exchange / 28 IV. ELECTRONIC PROPERTIES 30 A. Electrochemistry / 30 B. Paramagnetism / 32 C. Photochemistry / 32 V. CLUSTERS AS BUILDING UNITS 33 A. Extended Solid Frameworks / 33 B. Supramolecular Assemblies / 36 VI. CONCLUDING REMARKS 38 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 38 ABBREVIATIONS 38 REFERENCES 39 1. INTRODUCTION Over the past two decades, considerable progress has been made in the synthesis and characterization of compounds containing discrete hexanuclear clusters (1–12). Most recently, soluble, molecular forms of these clusters have begun to see use as building units in the construction of extended solid frameworks and supramolecular assemblies. In our view, certain hexanuclear cluster cores are very much akin to a new transition metal ion, but one with a large radius, a fixed coordination geometry, and electronic properties that can be adjusted through synthesis. -

Review of Unit I in Which We Develop a Model for the Atom and Explore the Structure of the Periodic Table

Review of Unit I In which we develop a model for the atom and explore the structure of the periodic table. 1. The following data are available for the element X: photoelectron spectrum: five peaks covalent radius: 0.099 nm first ionization energy: 1.251 MJ/mol core charge: +7 (a) Identify the element and explain your reasoning. In PES, each peak represents a unique atomic orbital. The peak’s energy gives the ionization energy of an electron in the associated atomic or- bital and the peak’s height is proportional to the number of equivalent electrons occupying the atomic orbital. Because X has five PES peaks we know it 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, and 3p electrons. The 10 electrons in the 1s, 2s, and 2p orbitals are core electrons that screen the valence electrons from “seeing” the full nuclear charge. The element’s atomic number, Z, is the sum of the core charge as “seen” by the valence electrons and the number of valence electrons; in this case the atomic number is 17 and X is chlorine. (b) How many valence electrons does the element have? Chlorine has seven valence electrons. (c) Element Y has one more proton than X. Is the AVEE for Y larger than, smaller than, or the same as the AVEE for X? Element Y is Ar, which as a valence shell of 3s23p6 in contrast to that for chlorine of 3s23p5. The AVEE is the average of the ionization energy for an element’s valence electrons. Argon has one more proton than does chlorine, which increases the ionization energies of both the 3s and the 3p electrons; thus, argon has the greater AVEE. -

CHM1 Review for Exam 5 the Following Are Topics and Sample

CHM1 Review for Exam 5 The following are topics and sample questions for the first exam. Topics a. Electron configuration b. Atomic Radii 1. Mendeleev and the first periodic c. Electronegativity Table d. Ionization Energy 2. Information in the Periodic Table Orbital diagrams a. Groups (families) Changing Subshells i. Alkali (group 1) Spin pairing energies ii. Alkaline earth e. Electron affinity (group 2) 7. Formulas of some nonmetals iii. Noble gases a. Ions (group 18) i. Cations iv. Halogens (group ii. Anions 17) b. Periodic relationships v. Calcogens (group c. Activities 16) d. Relative sizes b. Periods (rows) 8. Periodic Trends in Electron 3. Metals, nonmetals and metalloids Configurations and orbital Main Group, Transition Metals, diagrams Rare Earth and Actinide Valence electrons 4. Periodic Table and Trends in (electrons in the outer most shell) Multiple Choice Questions 1. Which of the following elements 3. Which of the following elements is a noble gas? has the highest electronegativity (1) krypton (3) antimony (1) F (3) O (2) chlorine (4) manganese (2) Cl (4) S 2. What is a property of most 4. The amount of energy required to metals? remove the outermost electron from a gaseous atom in the (1) They tend to gain electrons ground state is known as easily. (2) They tend to loose electrons (1) first ionization energy easily. (2) activation energy (3) They are poor conductors of (3) conductivity heat. (4) electronegativity (4) They are poor conductors of electricity. CHM1 Review for Exam 5 5. When an atom of phosphorus 9. Which famous scientist becomes a phosphide ion (P3-), developed a the first periodic the radius table? (1) decreases (1) Mendeleev (2) increases (2) Dalton (3) remains the same (3) Bohr (4) Thompson 6.