Field Trip Guide to the Sooke Formation Rocks and Fossils of Muir Creek Beach, Southwestern Vancouver Island, BC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Courtenay, Canada. Case Study

CITY OF COURTENAY, CANADA CASE STUDY. How to minimize health Client: City of Courtenay, British Columbia, Canada Sector: Municipality and safety risks to Background: Population 25,000. It is the urban and cultural hub of the larger employees, the public and community Comox Valley with many beaches, rivers and lakes and natural the environment by using outdoor recreational spaces No of machines: 1 MW-Series Foamstream. Areas treated: Asphalt, concrete and cobbles Previous methods used: Hand weeding, mechanical weed eaters Website: www.courtenay.ca/ BACKGROUND The City of Courtenay is on Vancouver Island. As a city, they are environmentally focused and concerned about their residents’ welfare and as such wanted to minimize exposure to unnecessary pesticides wherever possible. In 2007, they passed a law to regulate the non-essential use of pesticides in the city. This was in order to help minimize any potential risk posed to health or the well-being of the environment and was imposed on public and private land. TESTIMONIAL “Foamstream is a very safe product from both the perspective of the operator and the surrounding environment. It has created great interest with the public and even requests for us to treat private properties. Thanks to Foamstream we no longer have to worry about our operators injuring themselves or becoming fatigued and we can be confident that we won’t receive insurance claims for damage to vehicles which has happened with previous methods. The service support team at Weedingtech are brilliant and always on hand should we need help with our machines.” Barry Boguski - Public Works Services, City of Courtenay. -

A Sustainable Development Strategy for the District of Sooke – July 2008

A SSUSTAINABLE DDEVELOPMENT SSTRATEGY FOR THE DDISTRICT OF SSOOKE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.................................................................................................... 3 A COMMUNITY AT A THRESHOLD OF THE 21ST CENTURY.................................................. 3 THE ROLE OF THIS STRATEGY .......................................................................................... 4 CONTROL OVER CHANGE................................................................................................... 5 EIGHT PILLARS OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT............................................................. 5 CREATING THIS STRATEGY................................................................................................ 5 A SHARED VISION FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE.............................................................. 6 PRIORITIES......................................................................................................................... 6 Strategy #1: Create neighbourhood centres and a downtown waterfront that are compact and complete.................................................................... 8 Strategy #2: Develop a transportation system that provides viable opportunities for non-automobile transportation and transit use. ......... 11 Strategy #3: Support low-impact, energy-efficient, healthy buildings in which to live, work and play. ...................................................................... 15 Strategy #4: Celebrate cultural and ecological assets through the management -

Order in Council 42/1934

42 Approved and ordered this 12th day/doff January , A.D. 19 34 Administrator At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, arm~ame wane Aar. PRESENT: The Honourable in the Chair. Mr. Hart Mr. Gray Mn '!actersJn Mn !...acDonald Mn Weir Mn Sloan Mn ?earson Mn To His Honour strata r The LieLIRtneaftCOMPOtTrae in Council: The undersigned has the honour to recommend that, under the provisions of section 11 of the " Provincial Elections Act," the persons whose names appear hereunder be appointed, without salary, Provincial Elections Commissioners for the purposes of the said section 11 for the Electoral Districts in which they reside respectively, as follows :— ELECTORAL DISTRICT. NAME. ADDRESS. ESQUIMA IT Pilgrim, Mrs. Jemima Jane 1253 Woodway Ave.,Esquimall wins, John William Sooke Doran, John Patrick R.R. 2, Sooke Wilson, Albert Leslie Sooke Robinson, Robert William Colwood Yates, James Stuert Langford Wale, Albert Edward Langford Trace, John Luxton, via Colwood Field, Chester Gibb Metchosin Hearns, Henry 936 Craigflower Rd., Esq. Fraser, Neil 1264 Old Esquimalt Rd.,Esq. Hodgson, William 1219 Carlisle St., Mesher, James Frederick 1553 Esquimalt Rd., " Nicol, Mrs. Margaret 1411 Esquimalt Rd., " Clark, Mrs. Christina Jane Stuart Shirley, R.R.2, Sooke Alsdorf, Mrs. Katharine Iri s,Cobble Hill Barry, Mrs. Letitia Rosa Cobble Hill Barry, Tierney Patrick Cobble Hill Meiillan, Mrs. Barbara Ann Cobble Hill Dick, Robert Shawnigan Lake Havers, Arthur Robert Shawnigan Lake Garnett, George Grant Cobble Hill Dougan, Stephen David Cobble Hill Walker, Lady Emily Mary 649 Admirals Rd.,Esquimalt Walker, Eric Henry James 649 Admirals Rd.,Esquimalt Walker, William Ure Jordan River Brown, Mrs. -

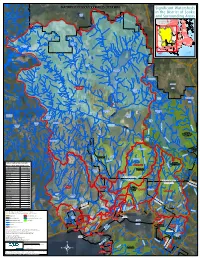

Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas

Shawnigan Lake C O W I C H A N V A L L E Y R E G I O N A L D I S T R I C T Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke Grant Lake and Surrounding Areas North C o w i c h a n V a l l e y Saanich R e g i o n a l D i s t r i c t Sidney OCelniptrahl ant Lake Saanich JdFEA H a r o S t r a Highlands it Saanich View Royal Juan de Fuca Langford Electoral Area Oak Bay Esquimalt Jarvis Colwood Victoria Lake Sooke Weeks Lake Metchosin Juan de Fuca Electoral Area ca SpectaFcu le Lake e d it an ra STUDY Ju St AREA Morton Lake Sooke Lake Butchart Lake Devereux Sooke River Lake (Upper) Council Lake Lubbe Wrigglesworth Lake Lake MacDonald Goldstream Lake r Lake e iv R e k o Bear Creek o S Old Wolf Reservoir Boulder Lake Lake Mavis y w Lake H a G d Ranger Butler Lake o a l n d a s Lake Kapoor Regional N C t - r i a s Forslund Park Reserve e g n W a a a o m r l f C r a T Lake r e R e k C i v r W e e e r a k u g h C r e Mount Finlayson e k Sooke Hills Provincial Park Wilderness Regional Park Reserve G o ld s Jack t re a Lake m Tugwell Lake R iv e r W augh Creek Crabapple Lake Goldstream Provincial Park eek Cr S ugh o Wa o Peden k Sooke Potholes e Lake C R Regional Park h i v a e Sheilds Lake r r t e r k e s re C ne i R ary V k M e i v e r e r V C Sooke Hills Table of Significant Watersheds in the e d i t d c Wilderness Regional h o T Charters River C Park Reserve District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas r e e k Watershed Name Area (ha) Sooke Mountain Sooke River (Upper) 27114.93 Boneyard Provincial Park Lake DeMamiel Creek 3985.29 Veitch Creek 2620.78 -

Agenda COWICHAN

MUNICIPALITY of North Agenda COWICHAN Meeting Regular Council Date Wednesday, September 7, 2011 Time 1:30 p.m. Place Municipal Hall - Council Chambers Page 1. Approval of Agenda Recommendation: that Council approve the agenda as circulated. 2. Adoption of Minutes Recommendation: that Council adopt the August 17, 2011 Regular Council meeting 5-11 minutes. 3. Addition of Late Items 3.1 Add Late Items Recommendation: that Council add the following late items to the agenda: 4. Presentations and Delegations 4.1 Municipal Awards Ceremony Recommendation: (Present Awards) 4.2 Hul'qumi'num' CD Presentation 13-14 Recommendation: (Receive liyus Siiye'yu - Happy Friends 2 CD) 5. Staff Reports 5.1 Horseshoe Bay Inn - Liquor Licence Amendment 15-19 Recommendation: that Council 1. require the Horseshoe Bay Inn to publish notice of the Inn’s application to the Liquor Control and Licensing Branch for a permanent change to the Inn’s liquor primary licence so that the Inn can start serving alcohol at 9:00 a.m. (instead of 11:00 a.m.) daily and, 2. direct staff to draft a bylaw to amend the Fees and Charges Bylaw to increase the fee to assess and comment on a permanent liquor licence amendment application from $25 to $100. 5.2 Aventurine Stones - Waterwheel Park 21-24 Recommendation: that Council direct the Chemainus Festival of Murals Society (at the Society’s expense and under the direction of Municipal staff) to 1. remove the stones from the Waterwheel parking lot in front of the Emily Carr # 2 mural / structure and repair the asphalt; 2. -

Cowichan Valley Trail Brochure (2021)

FLIP FOR MAP FOR FLIP treaded tires are highly recommended. recommended. highly are tires treaded Kinsol Trestle. Surface conditions vary so cyclists should note that that note should cyclists so vary conditions Surface Trestle. Kinsol reconnects with your start point in Duncan. Duncan. in point start your with reconnects south through forests and rural farmland before arriving at the Historic Historic the at arriving before farmland rural and forests through south Ganges. Catch another ferry from Vesuvius to Crofton and a short ride ride short a and Crofton to Vesuvius from ferry another Catch Ganges. Glenora Trails Head Park on Robertson Road. The trail route travels travels route trail The Road. Robertson on Park Head Trails Glenora from Swartz Bay, the route meanders along roads to the village of of village the to roads along meanders route the Bay, Swartz from This popular cycling and equestrian route starts and finishes at at finishes and starts route equestrian and cycling popular This Difficulty: Difficulty: Saanich Peninsula. After a quick ferry connection to Saltspring Island Island Saltspring to connection ferry quick a After Peninsula. Saanich Easy Distance: Distance: before connecting with the Lochside Trail and heading north up the the up north heading and Trail Lochside the with connecting before 26 km return km 26 ROUTE B — Glenora Trails Head Park to Kinsol Trestle Kinsol to Park Head Trails Glenora — B ROUTE route continues on the Galloping Goose Regional Trail into Victoria Victoria into Trail Regional Goose Galloping the on continues route dropping into Langford, along the Sooke Hills Wilderness Trail. The The Trail. -

Sooke + Nanaimo

SOOKE + NANAIMO DAY 1 Full-day in Sooke Take a 90-minute ferry sailing on the MV Coho from Port LUNCH Jordan River Angeles, WA to downtown Victoria, BC. Depart downtown AFTERNOON Victoria and drive approximately 2 hours on the Pacific Marine • China Beach Take a short walk to the western end of the beach Circle Route to Soule Creek Lodge in Port Renfrew. to the waterfall or wander at length to the east. Approximate hiking time: 30 minutes round-trip. FIRST NIGHT + NEXT DAY BREAKFAST • Soule Creek Lodge in Port Renfrew Perched high on the San • French Beach A wide swatch of green lawn fronts this sand and Juan Ridge with 360 degree panoramic views of the Pacific pebble beach where visitors can relax and enjoy a picnic or take a Ocean and 160 private acres filled with wildlife. Enjoy ocean-view cool dip in the ocean. accommodation in a lodge suite, yurt, or cabin with a wonderful Approximate hiking time: 15 minutes round-trip. hot breakfast included with your stay. • Whiffin Spit A natural breakwater just south of Sooke which is part of the Quimper Park. It is the perfect spot to sit back and SUGGESTED MORNING ACTIVITIES take in the beautiful Juan de Fuca Strait and the Sooke Basin. • Avatar Grove A phenomenal stand of giant old-growth red cedar and Douglas fir alongside the Gordon River within the traditional DINNER territory of the Pacheedaht First Nation. Beautiful fern-draped • Stone Pipe Grill Made Fresh, Made Here. Cheesecake, soup, creeks with moss-covered rocks and small waterfalls meander burgers, fries, and sauces are all made on site. -

Sooke, Port Renfrew, Nanaimo + Tofino

SOOKE, PORT RENFREW, NANAIMO + TOFINO DAY 1 LUNCH 17 Mile House Pub Seventeen miles from Victoria City Hall, this TRANSPORTATION pub has retained its yesterday charm. There is even a hitching post Take the scenic 90-minute morning sailing on the MV Coho from for visitors arriving by horseback. Creative West Coast fare and Port Angeles, WA to downtown Victoria, BC. local seafood can be enjoyed looking out over the garden or next to Follow along a portion of the rugged Pacific Marine Circle Route the crackling fire. from downtown Victoria to Sooke, Port Renfrew, and Lake Cowichan Stickleback West Coast Eatery The true West Coast, with a nat- on your way to Nanaimo. This coast to coast journey of Vancouver ural cedar bar, a stunning mural of Sombrio Beach and great food! Island offers panoramic views of the Juan de Fuca Strait. Enjoy a The menu offers everything from house-made burgers and wraps to quieter way of life while visiting spectacular provincial parks and pasta and baby back ribs. pastoral landscapes. AFTERNOON ACTIVITY SUGGESTIONS Please Note: This is a remote route with limited services. Some • Sooke Coastal Explorations Invigorating salt-filled ocean air sections may be narrow and sharp, and driving times may vary and ever-changing seascapes are the backdrop for this eco- depending on the type of vehicle. Please exercise caution while driving. adventure tour. Take an exhilarating boat ride that will leave you Depart downtown Victoria and enjoy a leisurely 40-minute drive with a deep appreciation for the enchanting creatures that to Sooke along the southern coast of Vancouver Island. -

Juan De Fuca Trail – Hiking/Backpacking Guide

Juan de Fuca Trail – Hiking/Backpacking Guide By Candice Camera Brief Background of the JDF Trail The Juan de Fuca Trail is a located in Juan de Fuca Provincial Park on Vancouver Island. The 47KM trail goes from China Beach to Botanical Beach near Port Renfrew. How to Get There (from Vancouver via transit) From Vancouver, we took a Pacific Coach bus onto the ferry from Tsawassen to Swartz Bay. We then took the same bus into downtown Victoria. In order to access the JDF trailhead, we had to purchase a round trip ticket on a private shuttle bus from Downtown Victoria. The shuttle bus service we used was West Coast Trail Express. A rough cost estimate for shuttle bus transportation to the trail head is about $120 round trip per person. Once we we’re on the bus, it’s about an hour bus ride to China Beach, which is where we started our hike. The shuttle will drop you off on the side of the road and you’ll find the trailhead in the trees. Trail Facts/Map The terrain on the Juan de Fuca Trail is rugged and exceptionally muddy. Even though we hiked this trail in July, it rained for 2 out of the 4 days we were on the trail. The Juan de Fuca Trail is open May-September. We booked a backcountry trail permit about 2 weeks in advance, but the campsites are on a first-come first-served basis. You have to carry the trail permit with you. You can pitch a tent anywhere at the campsites, space isn’t typically an issue. -

Models of Tsunami Waves at the Institute of Ocean Sciences

Models of tsunami waves at the Institute of Ocean Sciences Josef Cherniawsky and Isaac Fine Ocean Science Division, Fisheries & Oceans Canada, Sidney, BC Port Alberni, March 27, 2014 Acknowledgements: Richard Thomson Alexander Rabinovich Kelin Wang Kim Conway Vasily Titov Jing Yang Li Brian Bornhold Maxim Krassovski Fred Stephenson Bill Crawford Pete Wills Denny Sinnott … and others! Our tsunami web site: http://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/science/oceans/tsunamis/index-eng.htm … or just search for “DFO tsunami research” An outline … oIntroduction oModels of submarine landslide tsunamis (4 min) oA model of a Cascadia earthquake tsunami (4 min) oTsunami wave amplification in Alberni Inlet (4 min) oA model of the 2012 Haida Gwaii tsunami (4 min) oQuestions Examples of models of landslide generated tsunamis in Canada - some references - Fine, I.V., Rabinovich, A.B., Thomson, R.E. and E.A. Kulikov. 2003. Numerical Modeling of Tsunami Generation by Submarine and Subaerial Landslides. In: Ahmet C. et al. [Eds.]. NATO Science Series, Underwater Ground Failures On Tsunami Generation, Modeling, Risk and Mitigation. Kluwer. 69-88. Fine, I. V., A.B. Rabinovich, B. D. Bornhold, R.E. Thomson and E.A. Kulikov. 2005. The Grand Banks landslide-generated tsunami of November 18, 1929: Preliminary analysis and numerical modeling. Marine Geology. 215: 45-57. Fine, I.V., Rabinovich, A.B., Thomson, R.E., and Kulikov, E.A., 2003. Numerical modeling of tsunami generation by submarine and subaerial landslides, in: Submarine Landslides and Tsunamis, edited by Yalciner, A.C., Pelinovsky, E.N., Synolakis, C.E., and Okal, E., NATO Adv. Series, Kluwer Acad. -

Western Canada Explorer Featuring Vancouver, Victoria and Whistler

Antioch Seniors AND TravelCenter Travel & Tours presents... 9 DAY HOLIDAY Western Canada Explorer featuring Vancouver, Victoria and Whistler July 24 - August 1, 2020 Tour Dates: Western Canada Explorer Unforgettable experiences await 9 Days • 15 Meals in Canada’s Golden Triangle featuring mountain gondolas, a First Nations cultural experience, a regional Foodie Tour and an incredible wildlife cruise. TOUR HIGHLIGHTS 4 15 Meals (8 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 4 dinners) 4 Round trip airport transfers 4 Spend 3 nights in cosmopolitan Vancouver 4 Take a panoramic tour of Vancouver to see its downtown core, spectacular North Shore and beautiful Stanley Park and visit Capilano Suspension Bridge 4 Travel the scenic “Sea to Sky Highway” to and enjoy the PEAK 2 PEAK experience, a 1.88-mile long gondola ride between Blackcomb and Whistler Mountains 4 Travel by BC Ferry to Vancouver Island and visit world-famous Butchart Gardens 4 Included city tour of Victoria with its delightful English flavor, red double-decker buses and Tudor-style buildings Cross the Capilano Suspension Bridge and enjoy views of the spectacular rainforest 4 Visit Victorian-era Craigdarroch Castle and take the walking Victoria Food Tour, a delicious culinary experience 4 Enjoy a First Nations Cultural Experience at the I-Hos Gallery DAY 1 – Arrive in Beautiful British Columbia featuring a weaving workshop and included lunch with traditional Welcome to Canada’s rugged Northwest in Vancouver and transfer Bannock bread to your hotel. Meet your Tour Manager in the hotel lobby at 6:00 4 Spend 2 nights at the illustrious Painter’s Lodge, located on the p.m. -

Visit and Study in Comox and Courtenay, British Columbia

© Comox Valley Tourism COMOX & COURTENAY BRITISH COLUMBIA > VANCOUVER ISLAND • www.comox.ca // www.courtenay.ca • Located on Vancouver Island • 225 km (2.5 hours driving) north from Victoria © Comox Valley Tourism • Population: Comox: 13,630 Courtenay: 24,100 Notable features: Small Town • Friendly village lifestyle and great Canadian immersion for international students • Public transit joins both communities for recration and entertainment • Downhill skiing/snowboarding located nearby at Mt. Washington • Vancouver is accessible by Ferry (Comox to Powell River) FROM ALPINE TO • Both communities combine culture, sports, education, breathtaking scenery and outdoor recreation OCEAN • Day trip options include Tofino, famous for surfing and whale watching The sister towns of Comox and Courtenay lie in Comox Main Attractions: Valley - the centre of a rich agricultural area on Vancouver • Mount Washington Alpine Resort: www.mountwashington.ca Island. The adjacent ski slopes of Mount Washington • Forbidden Plateau/Comox Lake: http://islandmountainrides.com Alpine Resort make it a popular winter sports centre. • Comox Glacier The Comox Recreation Commission offers 130+ different • Courtenay Museum and Palaeontology Centre: www.courtenaymuseum.ca recreational programs each quarter featuring arts • Courtenay Youth Music Centre: www.cymc.ca programs, sports, recreation and culture. The area is also • Crown Isle Golf Course: www.crownisle.com home to Vancouver Island’s largest provincial park and • Strathcona Provincial Park: www.vancouverisland.com/parks