Jennifer Messelink

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WINTER 2015/2016! This Guide Gets Bigger and Better Every Year! We’Ve Packed This Year’S Winter Excitement Guide with Even More Events and Festivals

WELCOME TO WINTER 2015/2016! This guide gets bigger and better every year! We’ve packed this year’s Winter Excitement Guide with even more events and festivals. But keep your toque-covered ear to the ground for the spontaneous events that happen, like last year’s awesome #yegsnowfight We’re all working together, as a community, to think differently, to embrace the beauty of our snowy season, and to make Edmonton a great winter city. Edmonton’s community-led, award-winning WinterCity Strategy is our roadmap for reaching greatness. We are truly proud to say that we are on our way to realizing all the great potential our winters have to offer. New for this winter, we’ve got a blog for sharing ideas and experiences! Check it out at www.wintercityedmonton.ca If you haven’t joined us on Facebook and Twitter yet, we invite you to join the conversation. Let us know how you celebrate winter and be a part of the growing community that’s making Edmonton a great place to live, work and play in the wintertime. Now get out there and have some wintry fun! www.edmonton.ca/wintercitystrategy Facebook.com/WinterCityEdmonton @WinterCityYEG / #wintercityyeg Edmonton Ski Club Winter Warm-up Fundraiser Saturday, Oct 3, 2015 Edmonton Ski Club (9613 – 96 Avenue) www.edmontonskiclub.com Start winter with the ESC Winter Warm-up Fundraiser! Join us for a pig roast and family games. Visit our website for more details. International Walk to School Week (iWALK) Oct 5 – 9, 2015 www.shapeab.com iWALK is part of the Active & Safe Routes to School Program, promoting active travel to school! You can register online. -

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

AASA-Annual-Report-M

ALBERTA ALPINE SKI ASSOCATION SPRING MEETING 2016 Silvertip Resort, Canmore, May 29th Learning from the Past… Focused on What’s Ahead. ALBERTA ALPINE SKI ASSOCATION SPRING MEETING 2016 Silvertip Resort, Canmore, May 29th President’s Report • 2015-16 Season Review • Sharing Our Stories • Legends Club • University Training Group • Series by the Numbers • Membership Data / Trends • Calgary Parks Grant • Sponsors & Partners Alberta Alpine – Sharing Our Stories AB Alpine engages with our members, and the AB ski community on a daily basis through multiple electronic platforms: Facebook, Twitter, and weekly e-blast. Website: www.albertaalpine.ca 160,000 annual visits Facebook: Alberta Alpine Ski Association 556,000 page views Twitter: @AlbertaAlpine Inside Track Newsletter (e-blast) 1552 Likes 913 Followers 599 Subscribers Alberta Alpine – Sharing Our Stories Thank you Shaw TV and the “Chasing Limits” show – their support continues to help promote ski racing in the public eye. We have had good feedback on the coverage and viewership of the COP Alpine Insurance FIS slaloms. Shaw hopes to repeat and expand their coverage for next season. 2015/2016 PROJECT GOALS Provide training opportunities with a training group/cohort outside of member clubs typical purview Provide training opportunities that are more economical than those accessible by individual member clubs Provide unique and high quality environments/equipment/development opportunities that are not typically available to member clubs U14 PROJECTS Fast and Female, Winter Speed Camp, Best of Best Spring Camp U16 PROJECTS Western Canadian Rising Stars, Winter Speed Camp, Whistler Cup, Europe Project, Provincial Team Integration, Best of Best Camp U18 PROJECTS Winter Speed Camp, Lake Louise DH NorAm Fore-Runner Project, U18 Canadian Championships, Spring Best of Best Camp Alberta Shines at NCCA Championships Erik Read won the men’s NCAA individual slalom and overall title as his Denver University went on to win the overall skiing championship. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

It's the Amazing

Just when you thought it was safe to go near the mailbox... It’s the amazing... MutantMutant PopPop C a t a l o g ONCE AGAIN IN THE ULTRA-TRADITIONALIST PHOTOCOPIED FORMAT! #38 This catalog is so far over due that the phrase “late” doesn’t begin to do the matter justice. Rather than spend this entire page offering up a wave of excuses and explanations—some lame, some valid—I’ll just refer anyone who cares to the Mutant Pop website: http://www.mutantpop.com, then click INTERVIEWS and select interview no. 10. That’s as complete a recita- tion of my discouragements and failings as anything.... I’m very sorry for any inconvenience that the “18 months of sloth” has caused. I’m actually a little amazed that I’m back with full avidity doing label stuff again—orders are shipping on time, and new stuff is once again being accumulated for the inventory here. The next wave of SRCDs is, at long last, in preparation— apologies and thanks are especially due to the long-suffering SRCD subscribers who have been patiently twiddling their thumbs waiting for me to get it back in gear. I thank you for your tolerance and kindness. While I may have earned a failing grade for my (non-)effort with Mutant Pop in 2001, the year was not a total loss. There may AttentionAttention DeficitDeficit have been only two MP releases for all of 2001, but they both kicked some major boo-tay... Take, for example, the full-length compact disc by ATTENTION DEFICIT, Adventures in Laissez-Faire Eco- nomics.. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course

MUSIC HISTORY 13 PAGE 1 of 14 MUSIC HISTORY 13 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 13 Course Title Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice x Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis • Social Analysis x Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This course falls into social analysis and visual and performance arts analysis and practice because it shows how punk, as a subculture, has influenced alternative economic practices, led to political mobilization, and challenged social norms. This course situates the activity of listening to punk music in its broader cultural ideologies, such as the DIY (do-it-yourself) ideal, which includes nontraditional musical pedagogy and composition, cooperatively owned performance venues, and underground distribution and circulation practices. Students learn to analyze punk subculture as an alternative social formation and how punk productions confront and are times co-opted by capitalistic logic and normative economic, political and social arrangements. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Jessica Schwartz, Assistant Professor Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes x No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 2 4. -

Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-Speaking Community in Alberta: 1882-2000

Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-speaking Community in Alberta Fifth Up-Date: 2008-2009 A project of the German-Canadian Association of Alberta © 2010 Compiler: Manfred Prokop Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-speaking Community in Alberta: 1882-2000. Fifth Up-Date: 2008-2009 In collaboration with the German-Canadian Association of Alberta German-Canadian Cultural Center, 8310 Roper Road, Edmonton, AB, Canada T6E 6E3 Compiler: Manfred Prokop 209 Tucker Boulevard, Okotoks, AB, Canada T1S 2K1 Phone/Fax: (403) 995-0321. E-Mail: [email protected] ISBN 0-9687876-0-6 © Manfred Prokop 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Quickstart ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Description of the Database ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Brief history of the project .................................................................................................................................... 2 Materials ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Sources ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity 2 Copyright © Sarah Thornton 1995 The right of Sarah Thornton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 1995 by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Reprinted 1996, 1997, 2001 Transferred to digital print 2003 Editorial office: Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Marketing and production: Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 1JF, UK All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any 3 form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ISBN: 978-0-7456-6880-2 (Multi-user ebook) A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 10.5 on 12.5 pt Palatino by Best-set Typesetter Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in Great Britain by Marston Lindsay Ross International -

Graphics Incognito

45 amateur, trendy, and of-the-moment. The irony, What We Do Is Secret the subject of spirited disagreement and post-hoc of course, being that over the subsequent two speculation both by budding hardcore punks decades punk and graffiti (or, more precisely, One place to begin to consider the kind of and veteran scenesters over the past twenty-five GRAPHICS hip-hop) have proven to be two of the most crossing I am talking about is with the debut years. According to most accounts, ‘GI’ stands productive domains not only for graphic design, (and only) album by the legendary Los Angeles for ‘Germs Incognito’ and was not originally INCOGNITO but for popular culture at large. Meanwhile, punk band the Germs, titled simply ����.5 intended to be the title of the album. By the time Rand’s example remains a source of inspiration The Germs had formed in 1977 when teenage the songs were recorded the Germs had been by Mark Owens to scores of art directors and graphic designers friends Paul Beahm and George Ruthen began banned from most LA clubsclubs andand hadhad resortedresorted to weaned on breakbeats and powerchords. writing songs in the style of their idols David booking shows under the initials GI. Presumably And while I suppose it might be possible to see Bowie and Iggy Pop. After the broadcast of a in order to avoid confusion, the band had wanted My interest has always been in restating Rand’s use of techniques like handwriting, ripped London performance by The Clash and The Sex the self-titled LP to read ‘GERMS (GI)’, as if it the validity of those ideas which, by and paper, and collage as sharing certain formal Pistols on local television a handful of Los Angeles were one word. -

Click to Download

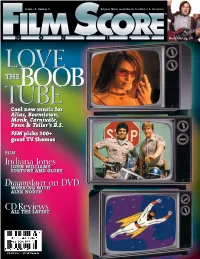

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress.