Accepted Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archbishop Temple Cetc

SERVICE 536 FULWOOD - ARCHBISHOP TEMPLE CETC From FULWOOD Nog Tow, Tag Lane, TANTERTON, Tanterton Hall Road, Tom Benson Way, COTTAM, Merry Trees Lane, Haydocks Lane, Cottam Way, Tom Benson Way, Tanterton Hall Road, Tag Lane, FULWOOD, Cadley Causeway, Blackbull Lane, Sharoe Green Lane and St Vincent's Road to FULWOOD Archbishop Temple CETC. Returning from Archbishop Temple CETC via outward route reversed to Tanterton Hall Road, then via Merry Trees Lane, Haydocks Lane, Cottam Way, Tom Benson Way, Tanterton Hall Road, Tag Lane to Nog Tow. FULWOOD Nog Tow 0740 COTTAM Tanterton Hall Road 0745 COTTAM Ancient Oak 0750 FULWOOD Cadley Causeway 0755 FULWOOD Black Bull 0807 FULWOOD Archbishop Temple CETC 0810 Service departs Archbishop Temple CETC 1455 Operator: Redline Travel SERVICE 656 BROADGATE – LEA – ARCHBISHOP TEMPLE CETC From BROADGATE Penwortham Old Bridge via Fishergate Hill, Corporation Street, Fylde Street, Fylde Road, Water Lane, Tulketh Road, ASHTON, Blackpool Road, LEA Aldfield Avenue, Dodney Drive, Tudor Avenue, Blackpool Road, West Park Avenue, Savick Way, Bus Turning Circle, Savick Way, West Park Avenue, Blackpool Road, Woodplumpton Road, Cadley Causeway, Black Bull Lane, Sharoe Green Lane and St Vincents Road to FULWOOD Archbishop Temple C.E. Technology College. Returning from Archbishop Temple CETC via outward route reversed to Ashton Blackpool Road then via LEA Aldfield Avenue, Dodney Drive, Tudor Avenue, Blackpool Road, West Park Avenue, Savick Way, Bus Turning Circle, Savick Way, West Park Avenue, Blackpool Road, Pedders Lane, Egerton Road, then reverse of outward route to BROADGATE. BROADGATE, Penwortham Old Bridge 0725 PRESTON Fylde Road 0735 ASHTON Tulketh Road 0740 LEA Aldfield Avenue 0745 SAVICK Savick Estate 0750 ASHTON Lane Ends 0755 FULWOOD Archbishop Temple CETC 0810 Service departs Archbishop Temple CETC 1455 Operator: Redline Travel SERVICE 820 PRESTON NEW HALL LANE – ARCHBISHOP TEMPLE CETC From PRESTON Jct. -

2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005 Made - - - - 1st February 2005 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Boundary Committee for England(a), acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(b), has submitted to the Electoral Commission(c) recommendations dated October 2004 on its review of the county of Lancashire: And whereas the Electoral Commission have decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: And whereas a period of not less than six weeks has expired since the receipt of those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Electoral Commission, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by sections 17(d) and 26(e) of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf, hereby make the following Order: Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005. (2) This Order shall come into force – (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005, on the day after that on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005. Interpretation 2. In this Order – (a) The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, established by the Electoral Commission in accordance with section 14 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.41). The Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (S.I. -

Central Lancashire Open Space Assessment Report

CENTRAL LANCASHIRE OPEN SPACE ASSESSMENT REPORT FEBRUARY 2019 Knight, Kavanagh & Page Ltd Company No: 9145032 (England) MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS Registered Office: 1 -2 Frecheville Court, off Knowsley Street, Bury BL9 0UF T: 0161 764 7040 E: [email protected] www.kkp.co.uk Quality assurance Name Date Report origination AL / CD July 2018 Quality control CMF July 2018 Client comments Various Sept/Oct/Nov/Dec 2018 Revised version KKP February 2019 Agreed sign off April 2019 Contents PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Report structure ...................................................................................................... 2 1.2 National context ...................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Local context ........................................................................................................... 3 PART 2: METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 4 2.1 Analysis area and population .................................................................................. 4 2.2 Auditing local provision (supply) .............................................................................. 6 2.3 Quality and value .................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Quality and value thresholds .................................................................................. -

536 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

536 bus time schedule & line map 536 Nog Tow - Cottam - Archbishop Temple Cetc View In Website Mode The 536 bus line (Nog Tow - Cottam - Archbishop Temple Cetc) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Fulwood: 7:45 AM (2) Nog Tow: 3:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 536 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 536 bus arriving. Direction: Fulwood 536 bus Time Schedule 26 stops Fulwood Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:45 AM Lightfoot Lane, Nog Tow Tuesday 7:45 AM Kidsgrove, Tanterton Alder Grove, Preston Wednesday 7:45 AM Threeƒelds, Tanterton Thursday 7:45 AM Thistlecroft, Preston Friday 7:45 AM The Avenue, Tanterton Saturday Not Operational Bowling Field, Tanterton The Guild Merchant, Tanterton 440 Tag Lane, Preston 536 bus Info Direction: Fulwood Primary School, Cottam Stops: 26 Haydocks Lane, Lea Civil Parish Trip Duration: 33 min Line Summary: Lightfoot Lane, Nog Tow, Kidsgrove, Minster Park, Cottam Tanterton, Threeƒelds, Tanterton, The Avenue, Tanterton, Bowling Field, Tanterton, The Guild The Villas, Cottam Merchant, Tanterton, Primary School, Cottam, The Villas, Preston Minster Park, Cottam, The Villas, Cottam, The Ancient Oak, Cottam, Tag Croft, Tanterton, Cottam The Ancient Oak, Cottam Hall Lane, Tanterton, Dovedale Avenue, Ingol, Oaktree Ave, Ingol, Mayƒeld Ave, Ingol, Cadley Tag Croft, Tanterton Causeway, Cadley, Dunkirk Avenue, Cadley, St Anthonys Drive, Cadley, Boys Lane, Fulwood, Leisure Cottam Hall Lane, Tanterton Centre, Fulwood, Janice Drive, -

45 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

45 bus time schedule & line map Preston - Blackburn Via Fulwood, Royal Preston 45 Hospital, Goosnargh, Whittingham, Salesbury, View In Website Mode Wilpshire The 45 bus line (Preston - Blackburn Via Fulwood, Royal Preston Hospital, Goosnargh, Whittingham, Salesbury, Wilpshire) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Blackburn Town Centre: 6:15 AM - 6:55 PM (2) Longridge: 7:55 PM (3) Preston City Centre: 6:30 AM - 7:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 45 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 45 bus arriving. Direction: Blackburn Town Centre 45 bus Time Schedule 72 stops Blackburn Town Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:35 AM - 5:35 PM Monday 6:15 AM - 6:55 PM Bus Station, Preston City Centre Tuesday 6:15 AM - 6:55 PM Gardner Street, Preston City Centre Margaret Street, Preston Wednesday 6:15 AM - 6:55 PM Gt George Street, Preston City Centre Thursday 6:15 AM - 6:55 PM North Road, Preston Friday 6:15 AM - 6:55 PM Frank Street, Preston City Centre Saturday 6:30 AM - 6:55 PM Aqueduct Street, Fulwood 15 Garstang Road, Preston Ripon Street, Fulwood 45 bus Info Direction: Blackburn Town Centre Symonds Road, Fulwood Stops: 72 111 Garstang Road, Preston Trip Duration: 79 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Preston City Centre, Methodist Church, Fulwood Gardner Street, Preston City Centre, Gt George Street, Preston City Centre, Frank Street, Preston City Highgate Close, Fulwood Centre, Aqueduct Street, Fulwood, Ripon Street, Fulwood, Symonds Road, Fulwood, Methodist Business Centre, Fulwood -

Preston Conservative Group 2 Summary 3 Preston City Council Cross-Party Working Group 5 Initial Proposals for Preston

Local Government Boundary Commission for England 14th Floor Millbank Tower Millbank London SW1P 4QP 6th November 2017 To whom it may concern, Following the publication of the Commission’s draft recommendations for the city of Preston, Preston City Council Conservative Group now submits and propose the following alterations. Firstly, we note that the proposed recommendation by the council and the Labour Party to divide the existing ward of Lea and Cottam into two separate wards has been adopted by the Commission. We submit that this proposed change will have an adverse effect on the residents living within those communities. In particular, we note that the draft proposals corrode community identity, disregard Lea and Cottam Parish Council and Ingol Neighbourhood Council, and presents too many varying local issues. This is diametrically opposed to the Commission's own statutory criteria, namely to preserve community identity, respect natural boundary lines, and provide effective and convenient local government. Furthermore, we note the significant differences between Cottam and Ingol, and Lea and Larches, and submit that at present Lea and Cottam resides in the Fylde Constituency. Any proposed separation would lead to less effective and convenient local government as residents will have too many overlapping representatives. Whilst we note the Commissions reluctance to take into consideration the boundaries of either constituencies or other forms of local government, we note that parish councils are to be used as ‘building blocks’ when establishing new wards or modifying existing ones. We re-submit that Lea and Cottam should remain whole and the additional housing within Summer Trees Avenue be included to achieve the required threshold for electoral equality. -

PRESTON, ETC • Health Office, Titheharn

86 PRESTON, ETC • •• • Health Office, Titheharn ·street Irvin street, 99 Ribbleton lane " Heap's yard,· 150 Friargate Isabella street, ll 7 Walker street Heatley street, 50 Friargate Isherwood street, 32 Deepdale Mill st Heaton bank, 294 New Hall lane Ivanhoe bank, 344 New Hall lane Henderson street, 82 Ripon street Ivy terrace, Waterloo .terrace, Ashton Henrietta street, 28 St. Mary's street Ivy terrace, Brockholes view . Herbert street, .Graham street · J acson street, Lancaster road Herbert terrace, 61 North road J ames street, 134 London road Hermon street, 324 Ribbleton lane Jamieson's buildings, Church street Hermon terrace, Watery lane Jemmett street, 32 Eldon street He:rschall street, Manchester road Jennet street, 34 Lawson stJJeet Hesketh mount, Sharoe Green lane. J essmund place, Marsh .lane Fulwood John William street, Fishwick road Hesketh street, 25 Waterloo rd, Ashton ·Jordan street, Fishergate Hesketh terrace, 446 New Hall lane Jutland street, 76 Meadow street Heyes' terrace, 28 Garstang road, Kay street, Marsh lane • Fulwood Kendal street,. 91 Friargate Heysham street, Hawkins street Kenmure place, Garstang rQad Higfdrd street, 8 New Hall lane Kent street, Great George's street. Higginson street, Lancaster road · Kensington terrace, Hartington road High street, 125 North road Kilshaw street, -Lancaster road Higher Bank road, Fulwood Kimberley road, Tulketh brow, Ashton / Highgate avenue, Garstang rd, Fulwood Kimberley terrace, 374 New Hall lane Highgate ter, Garstang rd, Fulwood Kingfisher street, 41 Castleton road Highgate -

NOTICE of POLL Preston City Council Election of a City Councillor for the Ashton Ward Notice Is Hereby Given That: 1

NOTICE OF POLL Preston City Council Election of a City Councillor for the Ashton Ward Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a City Councillor for Ashton will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of City Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BALSHAW 144 Tulketh Road, Independent David Macmillan (+) Wendy J. Brown (++) Michael Arthur Ashton-on-Ribble, Preston, Lancs., PR2 1AR DABLE 27 Rose Terrace, Liberal Democrats John J. Potter (+) Rebecca Potter (++) Jeremy Ashton, Preston, PR2 1EB HULL (Address in Preston) Labour Party Edward H Smith (+) Jennifer Smethurst (++) James Thomas SLATER (Address in Preston) Conservative Party Robert Jones (+) Claire N. Jones (++) Tes Candidate WALSH 8 Egerton Court, The Green Party Barbara A Wilde (+) Richard K Wilde (++) Anne-Marie Egerton Road, Ashton, Preston, PR2 1EH 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled to vote thereat Ashton Community Science College, Aldwych Drive, Ashton 1 AS1-1 to AS1-1223 St. Andrew`s Church Hall, Tulketh Road, Preston 2 AS2-1 to AS2-881 St. Andrew`s -

Blood Clinic Timetable

Blood Clinic Timetable You may attend any clinic on the timetable, no appointment is necessary, but waiting may be unavoidable during busy periods, please arrive at least 15 minutes before the session ends to ensure you will be seen, as clinics close and samples are collected promptly. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday AM THE MINERVA HC THE MINERVA HC HEALTHPORT HEALTHPORT THE MINERVA And 08.00-11.30 08.00-11.30 08.00-11.30 HCA and HEALTHPORT HEALTHPORT 08.00-11.30AM SAUL ST CLINIC BROOKFIELD FULWOOD CLINIC 08.00-11.30 08.45-11.30 CLINIC and and LONGRIDGE INGOL HC GEOFFREY ST HC HOSPITAL 08.45-11.30 08.45-11.30 08.45-11.30 LONGRIDGE HOSPITAL 08.30-12.00 PM MINERVA MINERVA HEALTHPORT HEALTHPORT NO CLINICS 12.45-16.00 12.45-16.00 12.45-16.00 12.45-16.00 FRIDAY PM INGOL HC and RIBBLETON ASHTON HC LONGRIDGE HOSPITAL CLINIC 13.00-16.00 13.00-16.00 13.00-16.00 RP HOSPITAL 17.00-19.00 Blood Clinic Timetable You may attend any clinic on the timetable, no appointment is necessary, but waiting may be unavoidable during busy periods, please arrive at least 15 minutes before the session ends to ensure you will be seen, as clinics close and samples are collected promptly. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday AM THE MINERVA HC THE MINERVA HC HEALTHPORT HEALTHPORT THE MINERVA And 08.00-11.30 08.00-11.30 08.00-11.30 HCA and HEALTHPORT HEALTHPORT 08.00-11.30AM SAUL ST CLINIC BROOKFIELD FULWOOD CLINIC 08.00-11.30 08.45-11.30 CLINIC and and LONGRIDGE INGOL HC GEOFFREY ST HC HOSPITAL 08.45-11.30 08.45-11.30 08.45-11.30 LONGRIDGE HOSPITAL 08.30-12.00 -

Stage 1 – Planning the Assessment

CENTRAL LANCASHIRE STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT September 2010 Although not published until later the main work on the Central Lancashire SHLAA was carried out prior to the revocation of the North West Regional Spatial Strategy (RSS) and therefore refers to RSS policies and housing targets. The Central Lancashire authorities are currently in the process of proposing local housing targets. The SHLAA will therefore be updated to remove references to the RSS and reflect local housing targets when these have been approved for publication within the joint Central Lancashire LDF Core Strategy. 2 CONTENTS Introduction Planning Policy Context Methodology Stage 1: Planning the assessment Stage 2: Determining which sources of sites will be included in the assessment Stage 3: Desktop review of existing information Stage 4: Determining which sites and areas will be surveyed Stage 5: Carrying out the survey Stage 6: Estimating the housing potential of each site Stage 7: Assessing when and whether sites are likely to be developed Stage 8: Review of the assessment Stage 9: Identifying and assessing the housing potential of broad locations Stage 10: Determining the housing potential of windfall APPENDIX 1 – Sites under 5 dwelling capacity included within the 5 year supply figures APPENDIX 2 A & B – GVA Grimley Stage 7c Report & Addendum List of Tables Table 1: Central Lancashire authority RSS housing targets Table 2: Chorley sites considered unsuitable Table 3: Preston sites considered unsuitable Table 4: South Ribble sites considered -

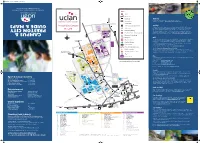

Campus & Preston City Guide & Maps

A2 map 2014_Layout 1 30/06/2014 15:08 Page 1 k u . c a . n a l c u . w w w 1 0 2 1 0 2 2 7 7 1 0 : l e T E H 2 1 R P , n o t s e r P , e r i h s a c n a L l a r t n e C f o y t i s r e v i n U ATM Bus routes Bus stops Walking Fit more walking into your daily life and reap the health benefits. 123 Bus number Walking routes and maps at www.uclan.ac.uk/sustainabletravel s p a m & e d i u G eat@UCLan Cycle compounds/lockers* Cycling Cycling is a great way of commuting as it is often quicker than other modes and a cheap and y t i C n o t s e r p Cycle racks healthy option. Preston and South Ribble benefit from over 50 km of traffic-free cycle paths PR1 2HE and a campus 20mph zone means that is has become safer to cycle on the roads too. Disabled parking The University's Bicycle User Group (BUG) has lots of information on cycling including shower & s u p m a C 4 Electric vehicle charging points and locker locations, information on free cycle training and guidance on bike security and safety. 4A For more information on UCLan cycle facilities visit www.uclan.ac.uk/sustainabletravel 40 23 41 Entrance to buildings 44 Mailroom Rail The University is conveniently situated within walking distance of Preston railway station making UCLan Sports Arena Ri Main reception the train an excellent mode for getting to UCLan. -

Clinical Placement Summary

Put the name of department or division here Clinical Placement Summary Placement Area: Acute Medical Occupational Therapy Placement Address: Core Therapies Department. Medical Room, Royal Preston hospital, Sharoe Green Lane, Preston. PR2 9HT. Telephone Number: (01772) 523224. Contact Name: Rowena Currie, (Clinical lead Occupational Therapist), Jane Taylor, (Specialist Occupational Therapist), Craig Tidswell, (Specialist Occupational Therapist). Nicola Thornton, (Specialist Occupational Therapist), Donna Chadwick, (Specialist Occupational Therapist). Placement Facilitator: Anita Burke, (Professional Lead for Occupational Therapy) Anne Tucker, (Core Therapy Lead). Type of Placement: Acute medicine. Encompassing the following specialty wards: Ward 18 Cardiology; Ward 20 Care of the elderly; Ward 23 Respiratory; Ward 24 Gastroenterology; Ward 25 Regional Renal Unit As and when required we also provide ongoing continuing care for medical outlying patients located in other areas of the hospital, for example on the: Medical Escalation Unit; Cardiac Catheter Lab, (CCL); Bleasedale Ward; Burns and Plastics; Gynecology Ward. Details of type of clients In-patient adults and older adults who can have complex, (multi) being dealt with: medical pathologies. Common medical conditions and patient presentation encountered: Ward 18 (Cardiology): Angina; Cardiovascular Disease: Heart Failure; Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy; Dilated Cardiomyopathy; Atherosclerosis; Atrial Fibrillation; Congenital heart disease; Arrhythmia; Coronary Artery Disease; Myocardial